The birth of Christian priesthood and hierarchical structures: From egalitarian communities to institutionalized religion

The establishment of a formal priesthood and hierarchical structures in Christianity marked a significant departure from the original ethos of the Jesus movement. In its earliest days, the Jesus community operated as a loosely organized and egalitarian network of believers, emphasizing mutual support, shared leadership, and spiritual equality. Over time, however, as the movement expanded, it adopted increasingly formalized structures of leadership and worship. This evolution was influenced not only by internal needs for organization and authority but also by the cultural and religious environment of the Roman Empire.

Ignatius, bishop of Antioch, proclaimed student of John the Apostle, 10th century, ceramic with glaze. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The egalitarian beginnings of the Jesus movement

In its earliest phase, the Jesus movement was characterized by:

- Egalitarian leadership: Early Christian communities often lacked a formal hierarchy. Leadership roles were fluid, with individuals chosen based on perceived spiritual gifts rather than appointed positions. Women, such as Phoebe (Romans 16:1) and Priscilla (Acts 18:26), played prominent roles, reflecting the inclusive ethos attributed to the movement.

- House churches: Early Christians met in private homes, where worship was informal and centered on communal meals, prayer, and teaching. The lack of designated sacred spaces reinforced the grassroots, community-based nature of the movement.

This decentralized model reflected the communal ideals of humility, mutual service, and personal spiritual transformation emphasized by early Christian teachings. However, as the movement grew and spread across the Roman Empire, the need for greater organization became apparent.

The emergence of leadership roles

By the mid-first century CE, the growing Christian movement began to formalize leadership roles to maintain order and cohesion among its scattered communities. Key developments included:

The rise of bishops and deacons

The emergence of defined leadership roles within early Christian communities is also documented in the Didache, one of the earliest Christian writings outside the New Testament. The Didache provides instructions on community practices, including the appointment of bishops and deacons, emphasizing their role in maintaining order and teaching. This text highlights the early church’s focus on service-oriented leadership, where bishops and deacons were chosen based on their moral character and alignment with the teachings of Jesus. It reflects the evolving structure of the Christian community as it sought to balance egalitarian ideals with the practicalities of managing growing congregations.

In the early Christian movement, bishops (episkopoi) and deacons (diakonoi) emerged as central figures to address the needs of expanding communities. Bishops initially served as overseers of local congregations, ensuring their spiritual and doctrinal integrity. This role, described in texts such as 1 Timothy 3:1–7, emphasized pastoral care, guidance, and fostering unity among believers. Their responsibilities often included resolving theological disputes and providing support to members of their communities.

In the early Christian movement, bishops (episkopoi) and deacons (diakonoi) emerged as central figures to address the needs of expanding communities. Bishops initially served as overseers of local congregations, ensuring their spiritual and doctrinal integrity. This role, described in texts such as 1 Timothy 3:1–7, emphasized pastoral care, guidance, and fostering unity among believers. Their responsibilities often included resolving theological disputes and providing support to members of their communities.

Deacons, on the other hand, managed practical aspects of communal life, such as distributing resources to the poor, organizing communal meals, and addressing logistical needs (Acts 6:1–6). Their work was essential in maintaining the day-to-day functioning of the community and ensuring that all members, particularly the marginalized, received care.

Both roles reflected the service-oriented ethos of early Christianity . However, as Christianity expanded into urban centers with larger congregations, bishops began to assume more centralized authority. This shift was driven by the practical necessity of coordinating increasingly complex communities and maintaining doctrinal consistency across geographically dispersed groups.

The role of elders

Elders (presbyteroi) played a significant role in teaching, providing pastoral care, and resolving disputes within the community. Initially, their position was closely tied to the communal nature of early Christianity, with responsibilities distributed among trusted members. Over time, the term presbyter evolved into “priest,” signifying the transformation of this role into a more defined clerical office. This development marked the beginning of a transition from shared leadership to a structured hierarchy.

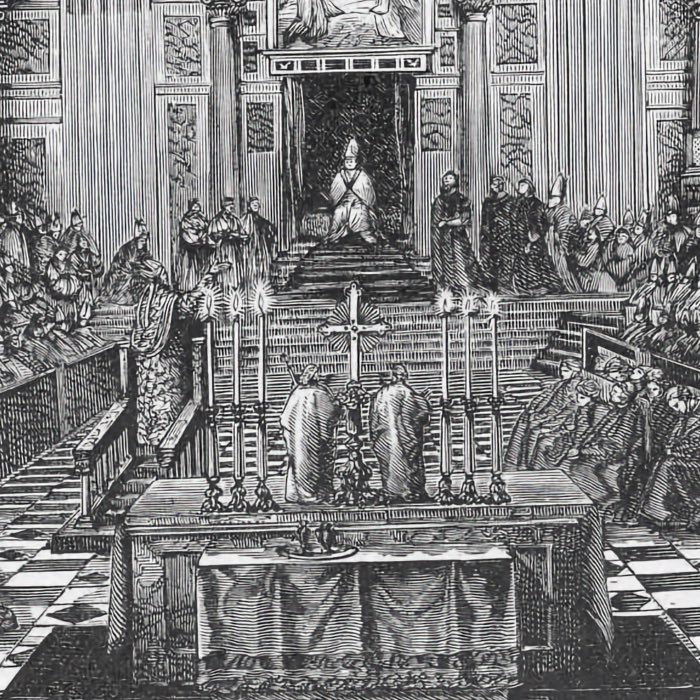

The consolidation of hierarchical structures

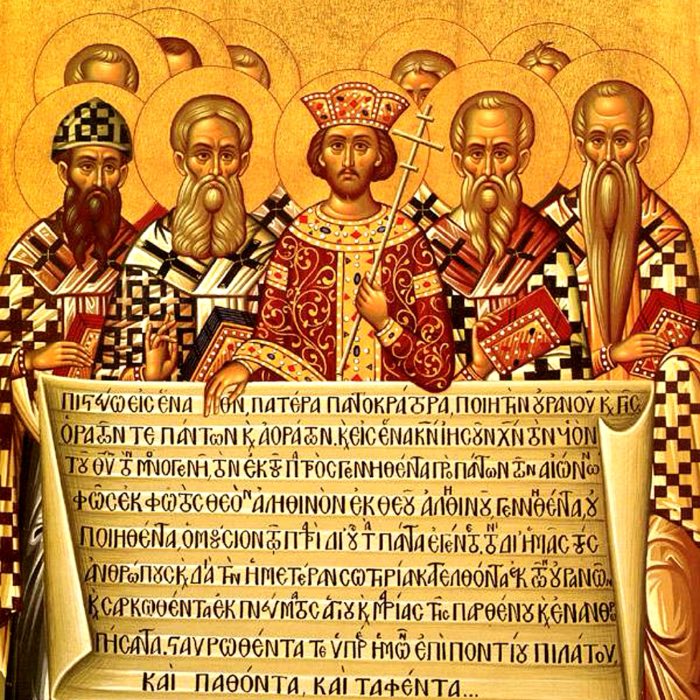

The belief in apostolic succession played a critical role in the consolidation of hierarchical structures within early Christianity . This concept posited that the authority of bishops could be traced back directly to the apostles, who were seen as the original emissaries of Jesus’ teachings. This theological foundation not only legitimized the authority of bishops but also reinforced the unity and continuity of Christian doctrine.

The turning point in the establishment of a formal hierarchy came with the rapid growth of Christianity in the second and third centuries. Key factors driving this consolidation included:

The turning point in the establishment of a formal hierarchy came with the rapid growth of Christianity in the second and third centuries. Key factors driving this consolidation included:

The need for unity and orthodoxy

As divergent interpretations of Christian doctrine emerged, the Church sought to unify its teachings and practices. Bishops became guardians of orthodoxy, tasked with defining and defending the “correct” interpretation of Christian faith.

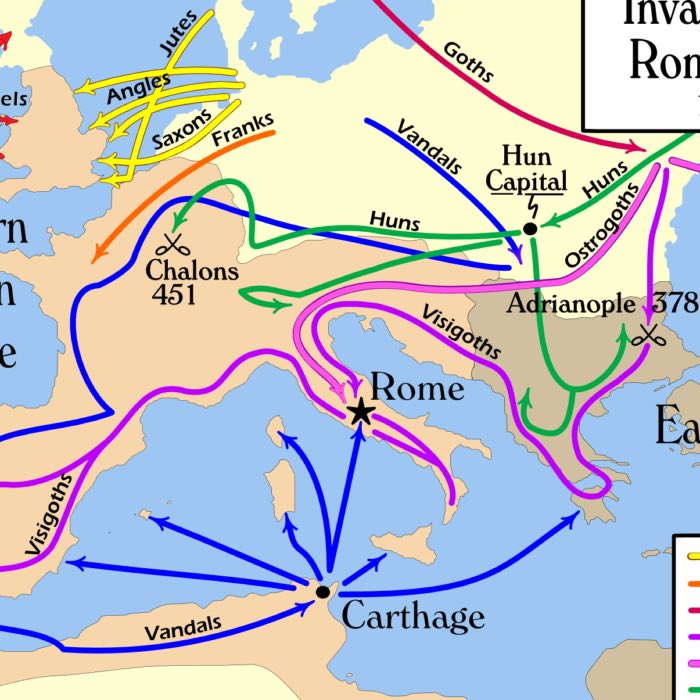

Roman administrative influence

The hierarchical and bureaucratic structures of the Roman Empire influenced the development of Christian leadership. As Christianity expanded, its leaders adopted organizational models that mirrored Roman political systems. Bishops, for example, began to preside over multiple congregations within a region, creating a network of dioceses akin to Roman provinces.

The role of persecution

Roman persecution of Christians paradoxically strengthened the Church’s hierarchical structures. During periods of persecution, bishops served as central figures, coordinating resistance, managing resources, and maintaining morale. Their prominence during these crises solidified their authority within the community.

The transition to priesthood

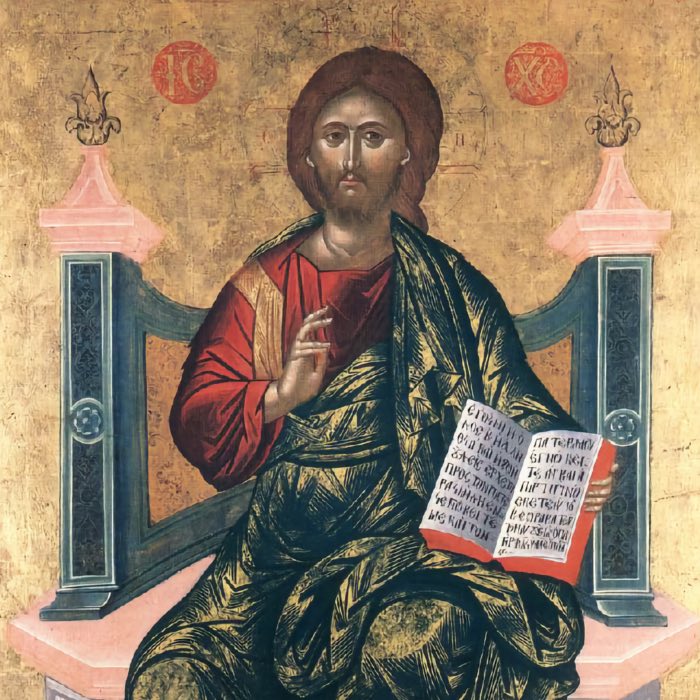

The concept of a Christian priesthood emerged gradually and was shaped by influences from both Jewish and Roman traditions. Early Christians, many of whom were Jews, drew inspiration from the Jewish priesthood, particularly the role of the high priest as a mediator between God and the people. This understanding was initially spiritualized, with Jesus himself regarded as the ultimate high priest, as reflected in texts like Hebrews 4:14–16. This perspective elevated Jesus’ role as a divine intercessor, emphasizing spiritual rather than ritualistic mediation.

Additionally, Roman religious practices contributed to the formation of the Christian priesthood. In the Roman tradition, priests oversaw public sacrifices and rituals, serving as intermediaries between the populace and the gods. As Christianity began to distance itself from its Jewish roots and sought to attract a broader audience, it adopted and adapted certain elements of Roman religious structures. This included the concept of a distinct clerical class, which mirrored the organizational and ceremonial roles seen in Roman religious institutions.

By the third century CE, the role of the Christian priest had evolved into that of a mediator of sacred rites, particularly the Eucharist. This marked a significant transition from the early emphasis on communal worship and direct access to God, to a more structured and institutionalized approach to religious practice.

Adoption of rituals and cultic practices

As Christianity grew, it absorbed elements of Roman and pagan traditions, both to facilitate conversion and to establish its identity within a culturally diverse empire. Key examples include:

Sacred spaces and vestments

From house churches to dasilicas: In the early years, Christians gathered in homes for worship and communal activities. These informal spaces reflected the grassroots nature of the movement and emphasized personal connections within the community. However, as Christianity gained legitimacy, particularly following Constantine’s Edict of Milan in 313 CE, the construction of dedicated places of worship began. These structures, known as basilicas, were inspired by Roman civic architecture, incorporating elements of grandeur and authority. This architectural transition symbolized the growing influence and institutionalization of the Christian faith.

Clerical vestments: Alongside the development of formal worship spaces, Christian clergy began to adopt distinctive robes. These vestments were modeled after Roman imperial and civic attire, signifying the elevated status of the clergy and aligning the Church with the traditions of the empire. The use of specific garments reinforced the hierarchical structure within Christian communities and highlighted the growing role of the clergy in religious and social life.

Festivals and holy days

Christianity also adapted and repurposed existing Roman and pagan festivals to align with its theological framework. For example, the celebration of Jesus’ birth was assigned to December 25th, coinciding with the Roman festival of Sol Invictus (“Unconquered Sun”). This strategic timing helped integrate Christian celebrations into existing cultural practices, facilitating the faith’s acceptance among diverse populations. Similarly, Easter, while rooted in Jewish Passover traditions, incorporated elements of spring fertility festivals, such as eggs and rabbits, which symbolized renewal and rebirth. These adaptations allowed Christianity to resonate with broader cultural traditions while maintaining its distinct religious identity.

The cult of saints and relics

The veneration of saints and relics became a cornerstone of Christian practice, drawing on the Roman tradition of hero cults. Just as Romans honored the remains and achievements of their heroes, Christians began to revere the relics of martyrs and saints, creating a tangible connection to the divine.

The institutionalization of worship

By the fourth century CE, Christian worship had undergone a significant transformation, becoming highly structured and ritualized. Formal liturgies were introduced, consisting of set prayers, readings, and rituals that provided a unified framework for worship across diverse Christian communities. These standardized practices reinforced a sense of shared identity and doctrinal consistency within the growing faith.

Sacraments, such as baptism and the Eucharist, evolved from their origins as simple acts of devotion into codified sacred rites. These rituals were administered exclusively by clergy, reflecting the increasingly hierarchical nature of the Church and emphasizing the special role of priests as mediators of divine grace.

The authority of bishops expanded during this period, as they assumed control over worship practices and ensured conformity within their jurisdictions. This centralization of authority not only solidified the bishops’ role as leaders but also reinforced the hierarchical structure that came to define the institutional Church.

The beginning of a dichotomy

The establishment of hierarchical structures and the adoption of rituals were not inherently negative. They provided cohesion, preserved Christian teachings, and facilitated the Church’s expansion. However, they also marked the beginning of a divergence between the simplicity of the early community ethos and the institutionalized religion that emerged. This dichotomy would grow over centuries, culminating in the heavily ritualized and hierarchical Church of the Middle Ages.

Conclusion

The development of the Christian priesthood and hierarchical structures was both a response to practical needs and a reflection of cultural influences. By adopting Roman administrative models and integrating elements of pagan worship, Christianity became a powerful and enduring institution. However, this institutionalization came at a cost: the gradual shift from the egalitarian and spiritual ethos of early Christian communities to a religion centered on hierarchy, authority, and ritual. While these changes enabled Christianity to survive and thrive in a complex and often hostile world, they also introduced tensions that continue to shape its identity.

References and further reading

- Udo Schnelle, Die ersten 100 Jahre des Christentums 30-130 n. Chr. - Die Entstehungsgeschichte einer Weltreligion, 2016, UTB, ISBN: 9783825246068

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bruce Manning Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The text of the New Testament – Its transmission, corruption, and restoration, 2005, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195166675

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 1 Die Frühzeit, 1996, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012632

comments