The spread of early Christianity

The emergence and spread of Christianity is one of the most significant transformations in human history. Rooted in Jewish apocalyptic expectations, early Christianity evolved into a universal religion that transcended its origins. Central to this transformation were historical figures such as Paul of Tarsus and the networks of early Christian communities throughout the Roman Empire. In this post, we examine the historical development of early Christianity, focusing on its dissemination, the role of key figures, and the cultural and social dynamics that facilitated its spread.

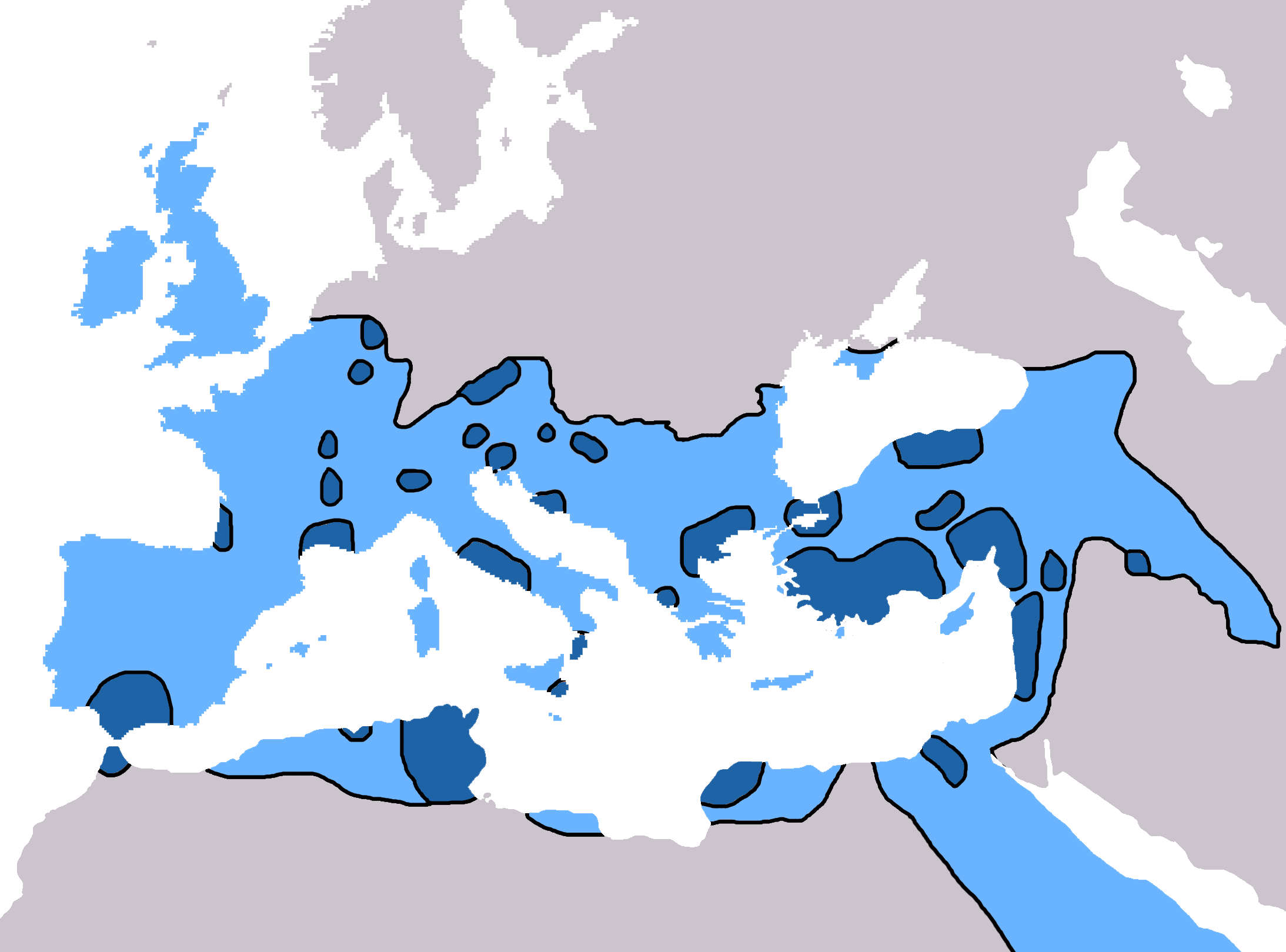

Map showing the spread of Christianity to 325 CE (dark blue) ans to 600 CE (light blue). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Paul of Tarsus: The architect of early Christianity

Paul of Tarsus, often regarded as the “Apostle to the Gentiles,” is the earliest historically verifiable figure in the development of Christianity. The seven authentic epistles attributed to Paul — including Romans, Galatians, and 1 Corinthians — provide critical insights into early Christian theology and the establishment of Christian communities. Paul’s writings reflect a celestial understanding of Jesus as a sacrificial figure within Jewish apocalyptic thought, whose death atoned for the sins of humanity and paved the way for divine intervention.

Paul’s role was transformative. He extended the reach of early Christianity beyond its Jewish origins by reinterpreting its message to appeal to non-Jewish audiences. In cities like Corinth, Ephesus, and Philippi, Paul established communities that would become the backbone of early Christian expansion. These urban centers were strategically chosen due to their prominence in trade and culture, allowing Paul’s message to spread widely. His theology emphasized faith in Jesus as the key to salvation, rendering adherence to Jewish law — such as circumcision and dietary restrictions — unnecessary for Gentile converts. This shift was pivotal in making Christianity accessible to a broader audience within the Roman world.

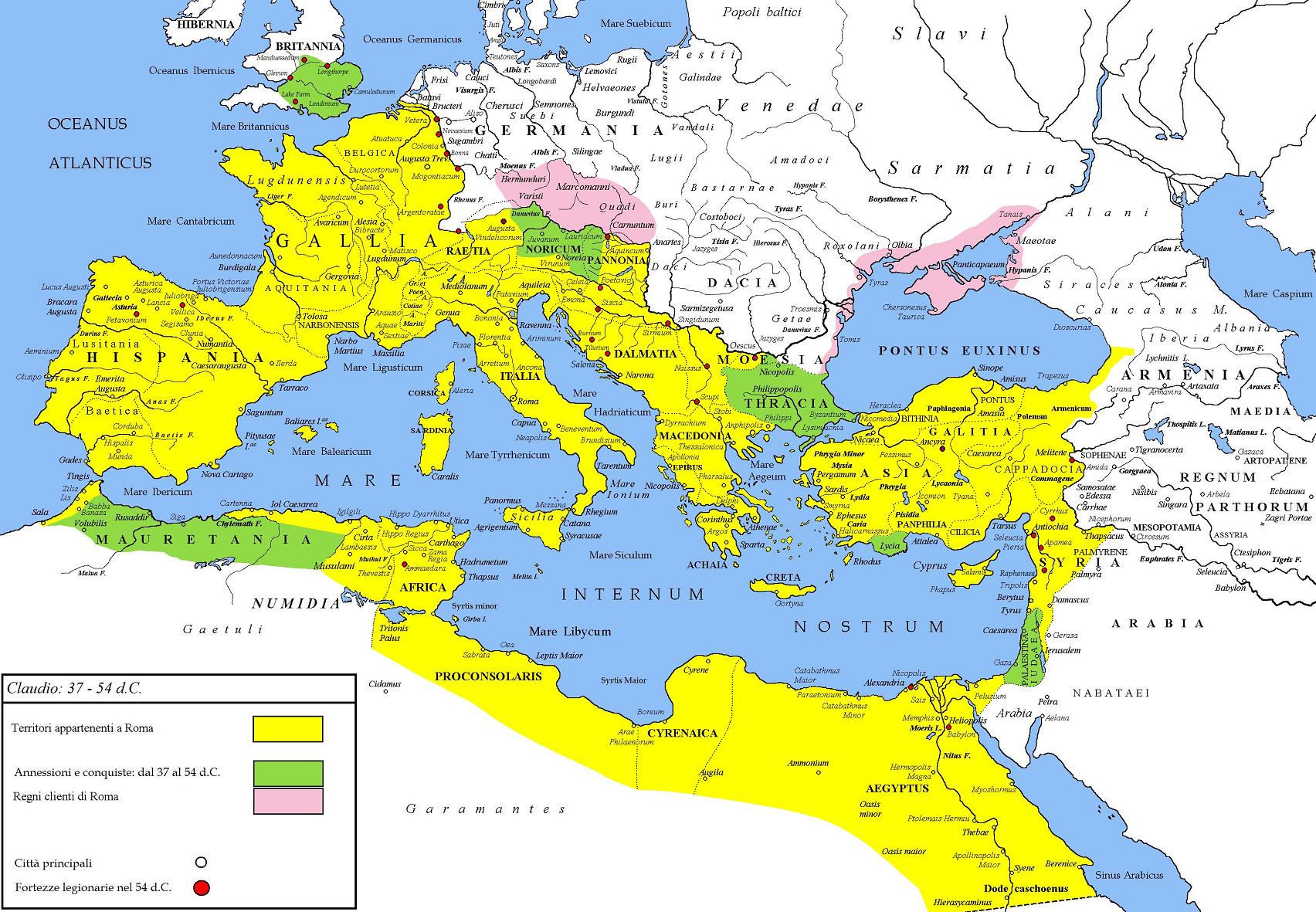

The Roman Empire during the reign of Claudius from 41 CE until his death in 54 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Historical sources, particularly the Acts of the Apostles and Paul’s own letters, document his extensive missionary journeys. Paul traveled across Asia Minor, Macedonia, and Greece, often facing significant resistance and persecution. In Philippi, for example, Paul and Silas were imprisoned after being accused of disturbing the peace (Acts 16:16-40). In Ephesus, his preaching against idolatry incited a riot among silversmiths whose livelihoods depended on the sale of idols (Acts 19:23-41). Despite these challenges, Paul’s efforts laid the groundwork for the establishment of a network of Christian communities.

Paul’s missionary journeys (modern map). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Paul’s epistles also reveal his theological innovations, including the concept of justification by faith and the universality of the Gospel message. His letters often addressed disputes within communities, such as divisions over leadership, ethical behavior, and the integration of Gentile converts. These writings not only guided early Christians but also shaped the foundational doctrines of Christianity, ensuring its doctrinal coherence as it spread.

Early Christian communities: Networks of faith

The spread of early Christianity relied heavily on the formation of small, tightly knit communities. These communities were often established in urban centers, where social and economic diversity provided fertile ground for new religious ideas. Early Christians gathered in private homes, forming “house churches” that served as centers for worship, teaching, and communal support. These gatherings were informal yet deeply significant, functioning as the nucleus of Christian social and spiritual life.

In these meetings, members shared meals, read scriptures, and discussed theological ideas, creating a participatory environment where all could contribute. The communal nature of these assemblies fostered a strong sense of belonging, particularly among marginalized groups such as the poor, slaves, and women, who found a voice and purpose within the Christian ethos. The promise of mutual aid and eternal life resonated deeply, contributing to Christianity’s early appeal and providing solace in an often oppressive Roman world.

Historical evidence suggests the existence of Christian communities in key urban centers across the Roman Empire, with varying levels of verification. For instance, the communities in Corinth, Philippi, and Ephesus are well-documented through Paul’s epistles, which provide detailed accounts of their challenges, disputes, and theological growth. The church in Rome, mentioned in Paul’s letter to the Romans, also has strong historical backing, as it became one of the most influential centers of early Christianity.

Some other communities, such as those in Antioch and Jerusalem, are widely acknowledged in both historical texts and later Christian traditions. Antioch is notable as the place where followers of Jesus were first called “Christians” (Acts 11:26), while Jerusalem served as a central hub for Jewish-Christian relations in the early years. Other communities, such as those in Thessalonica and Galatia, are verified primarily through Paul’s letters but lack extensive external corroboration.

However, certain early Christian communities remain more disputed in their historical authenticity. For example, the purported presence of Christians in places like Alexandria or Gaul during the earliest phases of Christianity is debated due to limited contemporary evidence. While later traditions affirm their existence, definitive proof from the 1st century is lacking. Nonetheless, the spread of these communities—both verified and disputed—highlights the remarkable adaptability and reach of early Christianity within diverse cultural and geographical contexts.

Christianity among Jewish colonies in the Roman Empire

Christianity’s initial spread was closely tied to Jewish diasporic communities throughout the Roman Empire. These communities provided the foundational network through which early missionaries, such as Paul, could disseminate Christian teachings. Synagogues often served as initial contact points, where Paul and others debated Jewish interpretations of messianic prophecies and introduced the Christian message. For example, Paul’s missionary efforts in cities like Thessalonica and Corinth often began in synagogues before extending to Gentile audiences.

While some Jews embraced the Christian reinterpretation of messianic prophecies, particularly the idea of Jesus as messiah fulfilling scriptural promises, many others resisted these claims. This resistance stemmed from theological differences and the perception that Christianity undermined traditional Jewish practices. Over time, these tensions led to a gradual separation between Judaism and Christianity, particularly as the latter attracted an increasing number of Gentile converts.

The theological divergence became more pronounced as Christianity incorporated Gentile converts and de-emphasized Jewish customs such as circumcision, dietary laws, and Sabbath observance. Paul’s epistles, such as Galatians, argued that adherence to the Mosaic Law was unnecessary for salvation, emphasizing faith in Jesus instead. This doctrinal shift allowed Christianity to establish a distinct identity, one that retained its Jewish roots for legitimacy while appealing broadly to non-Jewish populations. By the late 1st century, this separation was further solidified as Christianity evolved into a predominantly Gentile movement, distinct from its Jewish origins.

Broader adoption in Greco-Roman society

The broader adoption of Christianity within Greco-Roman society was facilitated by several interconnected factors:

- Philosophical resonance

Christian teachings on the nature of the soul, morality, and the afterlife found significant parallels in Greco-Roman philosophical traditions, particularly Stoicism and Platonism. For instance, Stoic ideas about virtue, the unity of humanity, and a rational divine order aligned closely with Christian ethics and theology. These similarities made Christianity intellectually appealing to educated classes while maintaining its distinctive religious identity. - Roman infrastructure

The extensive network of Roman roads and sea routes played a crucial role in the rapid dissemination of Christian ideas. Missionaries like Paul traveled these well-maintained routes to spread the Gospel across key urban centers of the empire. The interconnected nature of the Roman Empire also facilitated the exchange of letters, scriptures, and theological ideas among early Christian communities, ensuring doctrinal cohesion over vast distances. - Universal message

Christianity’s promise of salvation and its emphasis on equality before God resonated deeply with diverse populations, including marginalized groups such as slaves, women, and the poor. Unlike the exclusivity of many Greco-Roman religious cults, Christianity offered a message of inclusion and hope, emphasizing the inherent worth of every individual regardless of their social status. - Social networks and communal support

Early Christian communities provided robust social networks that appealed to those seeking solidarity and support in a vast and often impersonal empire. The practice of communal meals, mutual aid, and shared worship created strong bonds within these groups, making Christianity more than just a set of beliefs but also a deeply participatory way of life. - Persecutions and martyrdom

While persecutions were sporadic and localized, they played a paradoxical role in enhancing Christianity’s appeal. Martyrs—those who chose death rather than renounce their faith—became powerful symbols of conviction and resilience, inspiring admiration and curiosity among non-Christians. Over time, such acts contributed to the perception of Christianity as a faith worth suffering for, thereby attracting converts.

Why did Christianity resonate?

Christianity resonated because it addressed fundamental human concerns, offering hope, purpose, and a sense of belonging. In the Roman Empire, many “normal” people lived under harsh conditions, marked by economic inequality, political instability, and a lack of social safety nets. For marginalized groups, including the poor, slaves, and women, Christianity offered a vision of a just and loving God who valued every individual equally, providing a stark contrast to the hierarchical and often indifferent structures of Roman society. Its promise of salvation and eternal life appealed across social classes, especially to those disenfranchised by the dominant systems.

The religious landscape of the Roman Empire was highly diverse and experimental. Polytheism dominated public life, with state-sponsored worship of gods like Jupiter, Mars, and Venus reinforcing imperial authority. Mystery cults, such as those dedicated to Mithras or Isis, offered more personal and esoteric spiritual experiences but were often exclusive and limited to specific groups. For many, these religions failed to provide a sense of moral or spiritual fulfillment, focusing instead on ritual and civic duty without addressing deeper existential concerns. In this context, Christianity’s ethical teachings, such as love, forgiveness, and care for the vulnerable, offered a meaningful moral framework and a sense of purpose that contrasted with the often transactional nature of Greco-Roman religious practices.

The adaptability of Christianity was another crucial factor. As it spread, it incorporated elements of local cultures while maintaining its core message. For example, Christian communities adopted local languages, customs, and even architectural styles for their worship spaces, which helped them integrate into diverse settings. Whether in Jewish synagogues or Greco-Roman philosophical circles, Christianity’s flexibility allowed it to resonate with a wide array of cultural and social contexts, ensuring its survival and growth in a competitive religious environment.

Competing religious movements in the Roman Empire

Christianity was not the only movement gaining followers in the Roman Empire during its early centuries. The religious landscape was highly pluralistic, characterized by a diversity of traditions that competed for adherents. Mystery cults, philosophical schools, and traditional Greco-Roman polytheism all played significant roles in the spiritual life of the empire.

Mystery cults

Mystery religions, such as those dedicated to Mithras, Isis, and Demeter, offered initiates secret rituals and promises of personal salvation. The cult of Mithras, for example, was popular among Roman soldiers and emphasized themes of loyalty, cosmic struggle, and rebirth. Similarly, the cult of Isis appealed to a broad audience, including women, offering a compassionate goddess who provided protection and the hope of resurrection. These cults shared some characteristics with Christianity, such as the promise of salvation and communal identity, making them formidable competitors in the religious marketplace.

Greco-Roman polytheism

Traditional Greco-Roman religion, centered on the worship of gods like Jupiter, Venus, and Mars, was deeply intertwined with civic life. While it lacked the personal and moral engagement of Christianity, it served to reinforce political structures and communal identity. Festivals, sacrifices, and public ceremonies played vital roles in maintaining social cohesion, but these practices often failed to address individual spiritual needs, leaving room for more intimate and ethically oriented religions like Christianity to flourish.

Gnostic movements

Gnostic sects emerged as another significant competitor to orthodox Christianity. These groups, characterized by their esoteric teachings and dualistic worldview, emphasized personal enlightenment through secret knowledge (gnosis). Gnosticism often portrayed the material world as corrupt, created by a lesser divine being, and salvation as an escape to a higher spiritual realm. While some Gnostic ideas were absorbed into early Christian thought, orthodox Christianity eventually distanced itself from Gnosticism, branding it as heretical.

Philosophical schools

Philosophical schools such as Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Platonism also attracted significant followings. These schools provided ethical frameworks and ways of understanding the cosmos that resonated with many in the Roman elite. Stoicism, for instance, emphasized virtue, reason, and self-control, while Platonism explored the nature of the soul and the ultimate reality of a transcendent world of forms. Christianity often engaged with these philosophies, adopting and adapting ideas to make its teachings more intellectually compelling.

Why did Christianity prevail?

Despite the variety of competing movements, Christianity offered a unique combination of attributes that set it apart. Its emphasis on a personal relationship with a loving and just God, the promise of eternal salvation, and the inclusivity of its message appealed to a wide range of social classes. Moreover, the communal structure of Christian communities and their commitment to mutual support created a sense of belonging that many other traditions lacked. Over time, Christianity’s adaptability and its ability to incorporate elements from competing traditions allowed it to outlast and overshadow its rivals.

Conclusion

The development of Christianity was shaped by a convergence of historical figures, urban networks, and the diverse cultural dynamics of the Roman Empire. Emerging from Jewish apocalyptic thought, Christianity transitioned into a movement with broad appeal, aided significantly by the missionary activities of Paul of Tarsus and the establishment of cohesive urban communities. These communities served as hubs for theological development and mutual support, fostering a sense of belonging across social and economic strata.

Christianity’s success was not inevitable; it competed against established religious traditions, mystery cults, and philosophical schools that also sought followers. However, its adaptability, ethical teachings, and promise of salvation set it apart, enabling it to resonate with a wide array of cultural and social groups. By leveraging the infrastructure of the Roman Empire and engaging with contemporary intellectual and spiritual currents, Christianity expanded from a marginalized sect into a widespread faith tradition. From its early origins as a reinterpretation of Jewish apocalyptic thought, Christianity evolved into a movement with widespread appeal. Over time, it grew into an institution deeply embedded – and dominant – in societies and politics, exerting profound influence over the trajectory of civilizations for centuries to come – along with all the good and bad that came with it.

References and further reading

- Richard Carrier, On the historicity of Jesus – Why we might have reason for doubt, 2014, Sheffield Phoenix Press, ISBN: 9781909697492

- Ehrman, Bart D., The Triumph of Christianity: How a Forbidden Religion Swept the World, 2019, Oneworld Publications, ISBN: 978-1786074836

- Hurtado, Larry W., Destroyer of the Gods: Early Christian Distinctiveness in the Roman World, 2017, Baylor University Press, ISBN: 978-1481304740

- Pagels, Elaine, The Gnostic Gospels, 2006, W&N, ISBN: 978-0753821145

- Udo Schnelle, Die ersten 100 Jahre des Christentums 30-130 n. Chr. - Die Entstehungsgeschichte einer Weltreligion, 2016, UTB, ISBN: 9783825246068

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bruce Manning Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The text of the New Testament – Its transmission, corruption, and restoration, 2005, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195166675

comments