Dura-Europos: One of the earliest Christian house churches and oldest synagogues in a religious melting pot

The house church and synagogue at Dura-Europos, an ancient city on the Euphrates River in modern-day Syria, offer unique insights into the coexistence and evolution of early Christian and Jewish communities. Dating to the mid-3rd century CE, these structures are among the oldest known dedicated spaces for Christian and Jewish worship. Their simultaneous presence within the same urban setting – along with temples dedicated to Greco-Roman, Palmyrene, and local Mesopotamian deities – illustrates the intertwined histories of Judaism and Christianity, highlighting a time when these faiths developed side by side before Christianity emerged as a dominant religion within the Roman world.

The Palmyrene Gate, the principal entrance to the city of Dura-Europos. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Historical context of Dura-Europos

Dura-Europos, founded as a Hellenistic settlement around 300 BCE, became a cosmopolitan crossroads under successive Greek, Parthian, and Roman rule. By the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, it was home to a diverse population, including Greeks, Romans, Jews, Syrians, and others. This cultural melting pot fostered a unique blend of religious and artistic traditions.

Left: Map of Armenia under Tigranes II and parts of the Parthian Empire, with Dura-Europos located on the Euphrat River, beyond the South border of the Armenian Empire. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Aerial view of Dura in late 1930s. Yale University. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Left: Dura-Europos general excavations plan. Blue: Military and public buildings, Green: Religious buildings, Red: Baths, Orange: Dwellings and shops. The synagogue are labeled as “L7” and the house church as “M8”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Dura-Europos in Roman times, with the synagogue, the house church, the Temple of Baal, the Temple of Zeus, the Temple of Artemis, the Palace of Dux Ripae, and the citadel marked. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

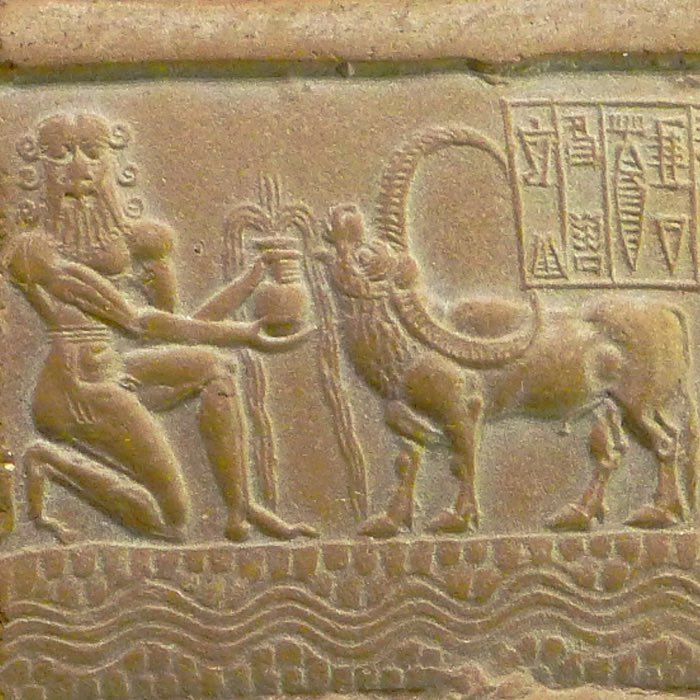

Judaism and early Christianity were not the only religions practiced in Dura-Europos. The city was also home to Greco-Roman, Palmyrene, and local Mesopotamian cults, as evidenced by temples dedicated to deities such as Zeus, Artemis, and Mithras. These cults, along with Judaism and Christianity, reflect the diverse religious landscape of the city, where multiple faiths coexisted and interacted. This rich tapestry of beliefs highlights the significance of Dura-Europos as a microcosm of the cultural and religious dynamics of the broader Roman and Near Eastern world.

Temple of Bēl, also known as the Temple of the Palmyrene gods, in Dura-Europos. The temple is known to be a center of religious life, where the god Iarhibol was worshiped. The origin of the god’s name, Bēl, comes from the influence of the cult of Bel-Marduk in Palmyra in 213 BC. Bel was known to be a chief god in pre-hellenistic times, often worshiped alongside Iarhibol and Aglibol. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Dura-Europos, founded as a Hellenistic settlement around 300 BCE, became a cosmopolitan crossroads under successive Greek, Parthian, and Roman rule. By the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, it was home to a diverse population, including Greeks, Romans, Jews, Syrians, and others. This cultural melting pot fostered a unique blend of religious and artistic traditions.

The tile (c. 200–256 CE) from the ceiling of a House of Scribes that bears a Greek inscription that identifies the man by name, Heliodoros, and occupation, actuarius (a title of officials of varying functions in the late Roman Empire). The style and technique of the figure — the frontal pose, large eyes, subtle shading, and earth-toned pigments — recall other painted decoration in the city’s buildings. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The city’s archaeological remains include temples dedicated to Greek, Roman, and Palmyrene gods, as well as the house church and synagogue. Both structures date to a period of relative tolerance, predating the more widespread Christian persecutions and showcasing the coexistence of different religious communities within the same urban landscape. Their discovery underscores the rich interplay of faiths in a society shaped by both Greco-Roman and Near Eastern influences.

Left: Altar of Yarhibol with Greek inscription by Scribonius Moucianus, a chiliarch (a military rank). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Relief with the god Arsu, from the Temple of Adonis. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Left: The stele from the Temple of Zeus Kyrios. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Relief of Aphrodite in a niche. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Relief from the Mithraeum (a temple dedicated to the god Mithras) in Dura-Europos. The relief depicts the god Mithras slaying a bull, a central motif in Mithraic iconography symbolizing creation and rebirth. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Timeline of known events at Dura-Europos

- c. 300 BC: Dura founded by the Seleucids as a fortress

- c. 113 BC: Parthians take Dura

- c. 65–19 BC: City walls constructed, including some towers

- c. 33 BC: Dura becomes a Parthian provincial administrative centre

- c. 17–16 BC: Palmyrene Gate begun

- 116 CE: Trajan takes Dura and triumphal arch built

- 121 CE: Parthians regain Dura

- 160 CE: Earthquake

- 164 CE: Romans under Lucius Verus again control Dura

- c. 168–171 CE: Mithraeum first built

- c. 165–200 CE: House converted to synagogue

- c. 211 CE: Dura a Roman colony

- post-216 CE: City walls heightened

- c. 224 CE: Parthians defeated by Sassanids

- c. 232–256 CE: House converted into a Christian chapel and decorated

- 238 CE: Graffito stating “Persians descended on us” was written

- c. 240 CE: Mithraeum rebuilt

- c. 244–254 CE: Synagogue paintings

- 253 CE: First Sassanid attack

- post-254 CE: Defensive embankment built to bolster city walls

- 256–257 CE: Dura falls to the Sassanid king Shapur I, the population was deported

The Dura-Europos house church

The Dura-Europos house church was originally a private residence, adapted to accommodate a small Christian community during the mid-3rd century CE. Measuring approximately 12 x 6 meters, the building underwent significant modifications.

The remains of the former house church in 2008. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Left: Church plan. Above right (6) is the baptistery. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Isometric drawing of the church. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

A large assembly room was created for communal worship, where scripture readings, prayer, and the Eucharistic meal would have taken place. Additionally, a baptistery was added to a side room, featuring a water basin for baptism, which was a central rite of Christian initiation.

Modern reconstruction of the canopy in the baptistry. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

These changes reflect the early Christian emphasis on communal worship and sacraments, while the modest scale illustrates the constraints and resource limitations faced by early believers in this period.

Iconography

The house church’s wall paintings are the earliest known examples of Christian figurative art. These murals blend biblical themes with local artistic styles, including:

- The Good Shepherd in the baptistery, symbolizing Christ as a caretaker and savior. This is one of the oldest known depictions of Jesus.

- Scenes such as Woman at the fountain and garden, Christ and Peter walking on the water, and Healing of the paralytic, emphasizing themes of sin, salvation, and resurrection.

Baptistery wall painting: Good Shepherd and Adam and Eve. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Left: Baptistery wall painting: Healing of the paralytic. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: The Samaritan woman at the well, or possibly Saint Mary. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Baptistry wall painting: David and Goliath with inscription, a scenery from the Hebrew Bible, indicating the strong connection between the Jewish and Christian traditions. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Liturgical and communal practices

The Dura-Europos house church provides a rare glimpse into the liturgical life of early Christians. The large assembly room suggests communal worship, including the reading of scripture, prayer, and the Eucharistic meal. The presence of a baptistery highlights the centrality of baptism, performed in a separate space to emphasize its ritual significance.

The spatial layout also reflects the intimate and egalitarian nature of early Christian gatherings. Unlike later basilicas, which emphasized hierarchical seating arrangements, the house church fostered a sense of communal equality, consistent with early Christian ideals.

The broader significance of the Dura-Europos house church

The discovery of the Dura-Europos house church is pivotal for understanding the transition of Christianity from a marginalized movement to an organized religion. Its modest size and simplicity illustrate the challenges faced by early Christians, who worshipped in secrecy or within the constraints of limited resources. Yet, its adaptations for worship reflect a growing sense of communal identity and theological coherence.

The church’s murals reveal the beginnings of a distinctly Christian visual language, rooted in local artistic traditions but imbued with theological meaning. This development marked a critical step toward the rich iconographic traditions that would flourish in later centuries.

The house church also challenges assumptions about the invisibility of early Christian communities. Far from being hidden or entirely persecuted, the Christians of Dura-Europos demonstrated resilience and adaptability, carving out spaces for worship in the complex cultural landscape of the Roman East.

The Dura-Europos synagogue

The synagogue at Dura-Europos, built around 244 CE – according because of an inscription found within the building – and thus contemporary with the house church, was also adapted from a private building. Its layout included a central hall for worship and a Torah shrine, indicating the community’s focus on scripture and prayer. The synagogue’s size and elaborate decorations suggest a well-established Jewish community with significant resources.

Courtyard of the synagogue, Western porch and prayer hall. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Isometric reconstruction of the L7 islet in Dura-Europos. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Left: Plan of islet L7 in Dura-Europos, with the synagogue (in red) and its outbuildings (in pink). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: pubCC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Restored plan of the first synagogue. 1: Central courtyard, 2: Community assembly hall, 3: Corridor, 4: Reception hall, 5: Reception hall, 6: Residential room, 7: Auxiliary room to the assembly hall. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Iconography

The synagogue’s murals are among the most remarkable examples of ancient Jewish art. These paintings depict biblical narratives, including stories about Moses, scenes from the Exodus, and figures such as David and Elijah, emphasizing themes of divine intervention and covenant. The use of figurative art in a Jewish context is notable, reflecting a localized departure from more aniconic traditions. The stylistic similarities between the synagogue and house church murals suggest a shared artistic milieu, shaped by the city’s multicultural environment.

Structure of the painted decoration in the (second) synagogue at Dura-Europos. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Identification of the west wall frescoes in Dura-Europos synagogue, showing a broad variety of scenes from traditional Jewish scriptures. Left source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: pubCC BY-SA 3.0); Right source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Left: Dura-Europos synagogue, fresco showing Moses leading the Israelites across the Red Sea, a temple., ca. 244-245 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: The Torah shrine of Dura-Europos synagogue. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

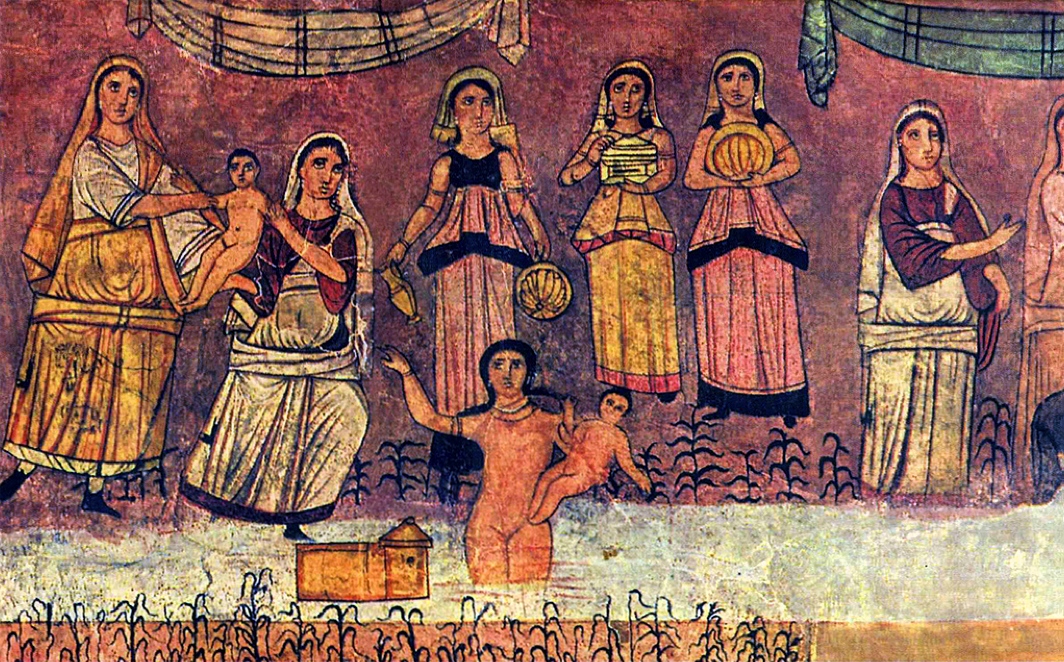

Left: Moses and the burning bush. Painting from Dura-Europos synagogue, third century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Finding of Moses, wall painting from the synagogue of Dura-Europos. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

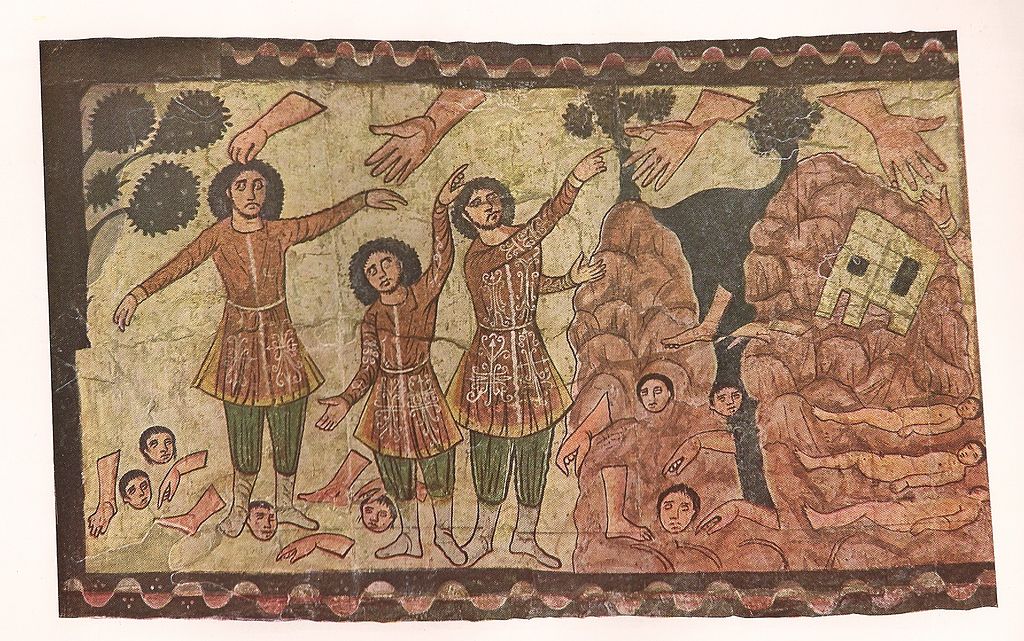

Resurrection of the dead (Vision of the Valley of Dry Bones), fresco from the Dura-Europos synagogue. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Men in togas and tunics witness the miracle performed by Elijah with the burning altar that been soaked with water, fresco from Dura-Europos synagogue. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Ezekiel and the hand of God. This scene from the synagogue at Dura-Europos depicts Ezekiel 37:1, a central passage in Jewish apocalypse literature. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Consecration of the Tabernacle (c. 245–256 CE), Dura-Europos synagogue fresco. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Broader significance of the synagogue

The Dura-Europos synagogue offers profound insights into the Jewish diaspora and their ability to maintain religious practices far from the ancestral homeland. The synagogue’s presence within the community highlights the substantial Jewish population in Dura-Europos and their capacity to construct and sustain such an elaborately decorated space for worship. This reflects the resilience of Jewish communities in preserving their traditions and religious identity after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE.

Additionally, the synagogue illustrates the shift towards rabbinic Judaism, where synagogues became central hubs for prayer, study, and community life, compensating for the absence of the Temple. The architectural layout and use of murals to narrate biblical stories suggest that synagogues served as both spiritual and educational spaces, reinforcing religious identity and practice.

Interestingly, the “format” of the synagogue — a gathering space with a central focus for communal prayer and teaching — shares notable similarities with what would later become the design of early Christian churches. This parallel underscores the interconnected development of these two traditions and highlights how shared cultural and practical influences shaped their worship spaces.

Coexistence and shared heritage

The simultaneous presence of the house church and synagogue at Dura-Europos offers a powerful illustration of the historical context in which Christianity evolved out of Judaism. During this time, the later stronger separation between the two had not yet developed, allowing for the coexistence of Christian and Jewish communities within the same urban and cultural space. Christianity, emerging as a sect within Judaism, initially shared much of its theology, rituals, and community structure with its parent tradition, highlighting the close and complex relationship between these faiths in their early stages of development. This shared heritage is evident in the architectural parallels, artistic influences, and cultural integration.

The architectural parallels between the house church and synagogue are striking, with both adapting domestic spaces to serve the needs of worshiping communities. This demonstrates the pragmatic strategies of these groups, transforming ordinary dwellings into sacred spaces that reflected their distinct yet overlapping religious practices.

Artistic influences also reveal a shared cultural framework. The murals in both structures incorporate narrative and stylistic elements that blend Greco-Roman and Near Eastern traditions, highlighting a common artistic vocabulary while expressing unique theological themes.

Furthermore, the cultural integration of these communities is evident in their engagement with the surrounding Greco-Roman and Near Eastern milieu. Both the synagogue and house church reflect a dynamic interaction with the diverse cultural and religious landscape of Dura-Europos, illustrating how these faiths navigated and adapted within a shared societal framework.

The coexistence of these faiths in Dura-Europos reflects a period when Christianity and Judaism lived side by side, interacting and evolving within a shared cultural framework. This relationship would later diverge, as Christianity became dominant and institutionalized.

Broader implications of the Dura-Europos discoveries

The house church and synagogue at Dura-Europos provide compelling evidence to counter simplistic narratives that portray early Christian and Jewish communities as existing in isolation or direct opposition. Instead, these groups were integral parts of a dynamic religious landscape, deeply influenced by shared cultural, artistic, and theological currents. The adaptive strategies they employed — seen in their architectural transformations and innovative artistic expressions — illustrate the efforts of these marginalized communities to assert their identities and preserve their traditions in a complex and often challenging environment. By repurposing ordinary buildings for sacred purposes and engaging with the artistic conventions of their time, both communities demonstrated remarkable creativity, carving out spaces that reflected their beliefs and cultural integration.

The looting and destruction by ISIS

The archaeological treasures of Dura-Europos, including its house church and synagogue, suffered significant damage and loss during the Syrian Civil War. Beginning in 2014, the site was extensively looted and partially destroyed by ISIS, a designated terrorist organization, which exploited such heritage sites for financial gain through illegal artifact trafficking and deliberate acts of cultural vandalism. These actions devastated one of the world’s most valuable records of early religious coexistence and artistic innovation.

The systematic looting not only resulted in the loss of countless artifacts but also inflicted irreversible harm to the historical context of the site, erasing connections that these objects held to their surroundings. Moreover, the deliberate destruction of cultural heritage at Dura-Europos and similar sites was intended as an ideological statement, aiming to erase symbols of religious and cultural diversity.

Conclusion

The Dura-Europos house church and synagogue stand as symbols of early religious expression and coexistence. Their shared architectural and artistic legacies provide invaluable insights into the historical context in which Christianity evolved out of Judaism. At this time, the later stronger separation between these two faiths had not yet developed, allowing them to exist side by side. As two of the oldest known spaces for dedicated worship, they exemplify a formative period when Christianity and Judaism were closely connected, shaped by a rich cultural and religious environment. These discoveries remind us of the early stages of Christianity’s development and its roots within the Jewish tradition, offering a window into the shared origins of two of the world’s major religions.

References and further reading

- Hopkins, C., The Discovery of Dura-Europos, 1979 Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300022889

- White, L. M., The Social Origins of Christian Architecture: Building God’s House in the Roman World : Architectural Adaptation Among Pagans, Jews, and Christians, 1996, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN: 978-1563381805

- Ted Kaizer, Religion, Society and Culture at Dura-Europos, 2021, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1107560239

- Baird, J. A., Dura-Europos, 2018, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN: 978-1472530875

- Udo Schnelle, Die ersten 100 Jahre des Christentums 30-130 n. Chr. - Die Entstehungsgeschichte einer Weltreligion, 2016, UTB, ISBN: 9783825246068

- Hans-Josef Klauck, Die religiöse Umwelt des Urchristentums, Band 1+2, Kohlhammer, ISBN 9783170103122

- Thomas Böhm, Peter Bruns, Wolfram Drews, Michael Durst, Michael Fiedrowicz, Johannes Franzkowiak, Reinhard Meßner, Eckhard Wirbelauer, Gerhard Philipp Wolf, Die Geschichte Des Christentums – Die Zeit des Anfangs (bis 250), 2005, Herder, Ungekürzte Sonderausgabe, Hrsg.: Norbert Brox, Jean-Marie Mayeur, Charles Piétri, Luce Piétri, ISBN: 3-451-29100-2

comments