The core teachings presented in the Gospels: A universal and transformative message

Understanding the essence of the teachings attributed to the figure of Jesus, as recorded in the New Testament’s Gospels, requires a focus on the values and themes central to these narratives. While the historical authenticity of these accounts remains debated, the ethical and spiritual vision they convey is radical and transformative. At the heart of the Gospel message is a call to universal love, humility, non-violence, and personal spiritual transformation. This narrative emphasizes inner moral integrity and compassion over external rituals or societal hierarchies. Thus, without the necessity of a historical Jesus, the message from the Gospels also works as a powerful and relevant framework for ethical and spiritual life.

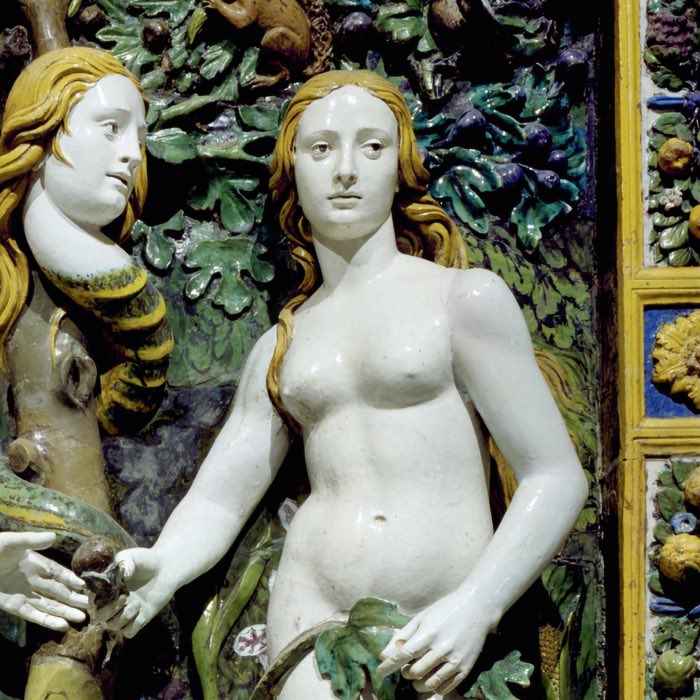

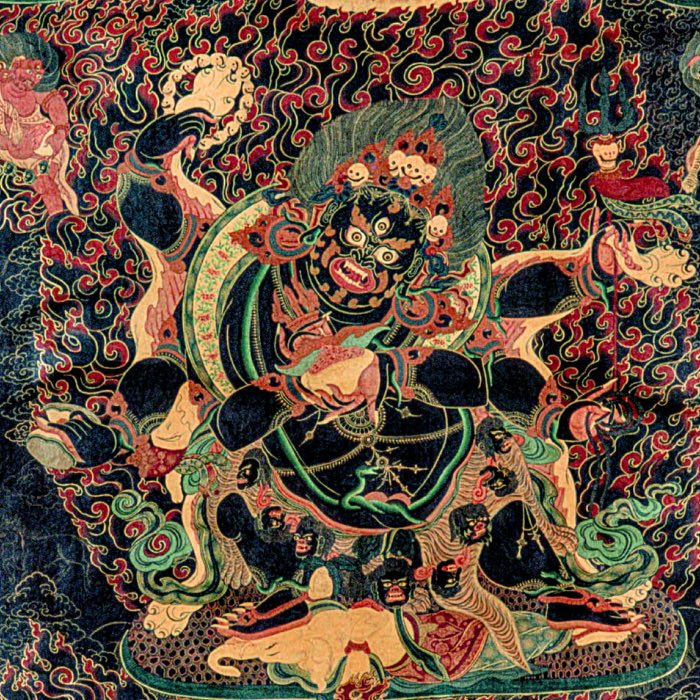

Christ with a burning heart, icon, Belarus, end of the 18th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (public domain)

What is a Gospel?

The term gospel comes from the Old English word godspel, meaning “good news” or “good message”. In German, for example, it is Evangelium or Frohe Botschaft, which also means “good message”. It translates the Greek word euangelion (εὐαγγέλιον), which was commonly used in antiquity to describe proclamations of important, joyful news — such as a military victory or the birth of a future ruler. In the context of early Christianity, the gospel refers to the “good news” about salvation, which centers on Jesus.

However, what exactly constitutes this “good news” depends on different interpretations:

The Gospel as the proclamation of the Messiah’s arrival

In its earliest form, especially within Jewish-Christian communities, the Gospel likely referred to the proclamation that the awaited Messiah had come. The message was that Jesus fulfilled Jewish messianic prophecies, had been vindicated by God through his resurrection, and would return to inaugurate the Kingdom of God.

Key components of this version of the Gospel:

- Jesus’s role as the Messiah (Christ, or “Anointed One”)

- His death and resurrection as acts of divine intervention for humanity’s salvation

- The promise of the coming Kingdom of God

This understanding is reflected in early Christian writings, such as Paul’s epistles (e.g., 1 Corinthians 15:3-4). For Paul, the Gospel primarily centers on the death and resurrection of Jesus, which he sees as the means by which God offers salvation to both Jews and Gentiles. In Romans 1:16-17, he writes:

“For I am not ashamed of the gospel, because it is the power of God that brings salvation to everyone who believes.”

Paul’s focus is less on Jesus’s earthly teachings and more on the theological significance of his death and resurrection as the path to reconciliation with God.

The Gospel as Jesus’s teachings

Another interpretation sees the Gospel as the core teachings of Jesus during his lifetime. In this view, the “good news” is the ethical and spiritual message Jesus preached about:

- The imminent arrival of the Kingdom of God (Mark 1:14-15)

- Living a life of love, compassion, humility, and forgiveness (Matthew 5-7, the Sermon on the Mount)

- Repentance and inner transformation as the way to participate in God’s Kingdom

This interpretation focuses on Jesus’s moral and spiritual guidance rather than the events of his death and resurrection.

The Gospel as a combination of both

For many early Christians, the Gospel encompassed both Jesus’s teachings and the proclamation of his death and resurrection. The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John present Jesus’s teachings alongside narratives of his crucifixion and resurrection, suggesting that the “good news” involves both his ethical message and his role in God’s salvific plan.

Later Church interpretations

As Christian doctrine developed, the Gospel came to be understood as the message of salvation through faith in Jesus Christ, as mediated by the Church. Over time, the institutional Church formalized the content of the Gospel, emphasizing:

- Belief in the Trinity (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit)

- The necessity of baptism and adherence to Church teachings

- The promise of eternal life for believers

Summary

In conclusion, the Gospel can be understood in different ways:

- As the announcement of the Messiah’s arrival and the events of Jesus’s death and resurrection

- As Jesus’s ethical and spiritual teachings about the Kingdom of God

- As a synthesis of both, emphasizing Jesus’s life, teachings, death, and resurrection

Which aspect is emphasized often depends on the theological perspective of the interpreter. For early Christians like Paul, the focus was primarily on Jesus’s death and resurrection as the fulfillment of God’s promise. However, Jesus’s teachings also form an essential part of the “good news” in the synoptic Gospels.

Jesus’s core teachings in the Gospels

In the following, we focus on the ethical and spiritual teachings attributed to Jesus in the Gospels, particularly in the synoptic Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. These teachings emphasize universal love, compassion, humility, and non-violence as the foundation of a transformative and ethical life. While the historical authenticity of these accounts is debated, the values they convey remain powerful and relevant across cultures and times:

Universal love and compassion

A cornerstone of the Gospel message is the call to unconditional love and compassion. In Mark 12:31, Jesus commands

“Love your neighbor as yourself,”

while in Matthew 5:44, this love is extended even to one’s enemies:

“Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.”

These teachings urge followers to transcend social, ethnic, and cultural boundaries, embodying a radical inclusivity.

The parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37) vividly illustrates this ethos. By portraying a despised Samaritan as the hero who exemplifies neighborly love, the narrative challenges entrenched prejudices and calls for acts of kindness regardless of societal expectations.

Faith in action and personal responsibility

In these Gospel accounts, faith is not confined to belief alone but must manifest in action. In Matthew 7:21, Jesus states

“Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but the one who does the will of my Father who is in heaven.”

This harmony between faith and action underscores the importance of personal responsibility in living out ethical principles.

The Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6:9–13) exemplifies the simplicity and universality of approaching the divine. It highlights a direct and personal connection to God, free from intermediaries or elaborate rituals. Yet, these teachings warn that external displays of piety hold little value if they are not rooted in love, compassion, and justice.

Humility and simplicity

Humility and detachment from material wealth are recurring themes in the Gospel narratives. In Matthew 5:3, it is declared:

“Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

Similarly, Mark 10:25 warns:

“It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.”

In Gospels, Jesus is depicted as living this ideal, traveling without possessions, relying on the generosity of others, and sharing meals with those marginalized by society. While wealth itself is not condemned, attachment to it is portrayed as a hindrance to spiritual growth and compassion.

Ethics of compassion and peace

The rejection of judgment and advocacy for forgiveness form a foundation for the Gospel ethic of compassion. In Matthew 7:1, Jesus cautions

“Do not judge, or you too will be judged,”

and in John 8:7, challenges self-righteousness, saying

“Let him who is without sin cast the first stone.”

These teachings promote introspection and understanding rather than condemnation.

The call to non-violence is another central aspect of this message. Matthew 5:39,

“Turn the other cheek”

challenges the instinct for retaliation, advocating for peace and forgiveness even in the face of aggression. This teaching is not a passive acceptance of injustice but an active refusal to perpetuate cycles of hatred and violence. It embodies the unconditional nature of compassion, recognizing the humanity in others, even adversaries.

Challenging religious authority

The Gospel figure frequently opposed the rigid legalism and hypocrisy of religious authorities. In Matthew 23:23, he admonishes the Pharisees:

“You give a tenth of your spices — mint, dill, and cumin. But you have neglected the more important matters of the law — justice, mercy, and faithfulness.”

The parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37) and the declaration that

“The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath”

in Mark 2:27 illustrate the belief that religious practices should serve human wellbeing rather than impose burdens. Genuine faith, according to these narratives, is demonstrated through loving action rather than rigid adherence to rules or hierarchies.

A universal and accessible path

The teachings attributed to Jesus do not depend on external structures such as rituals, dogmas, or institutions. The Gospel message calls for the active practice of love, humility, forgiveness, and service in everyday life. By embodying these values, individuals engage in a living spirituality that is deeply personal and profoundly impactful.

This perspective aligns with the depiction of the Kingdom of God as an inner reality (Luke 17:21):

“The Kingdom of God is within you”.

It suggests that spiritual growth and connection with the divine are accessible to all, unbound by intermediaries or elaborate systems. The vision of fellowship – “Where two or three gather in my name, there I am with them” (Matthew 18:20) – underscores the simplicity of spiritual community.

What the Gospels do not communicate

While the Gospels convey a rich and transformative ethical vision, there are notable aspects of religion that they do not explicitly advocate or endorse:

Rejecting exclusive claims to absolute truth

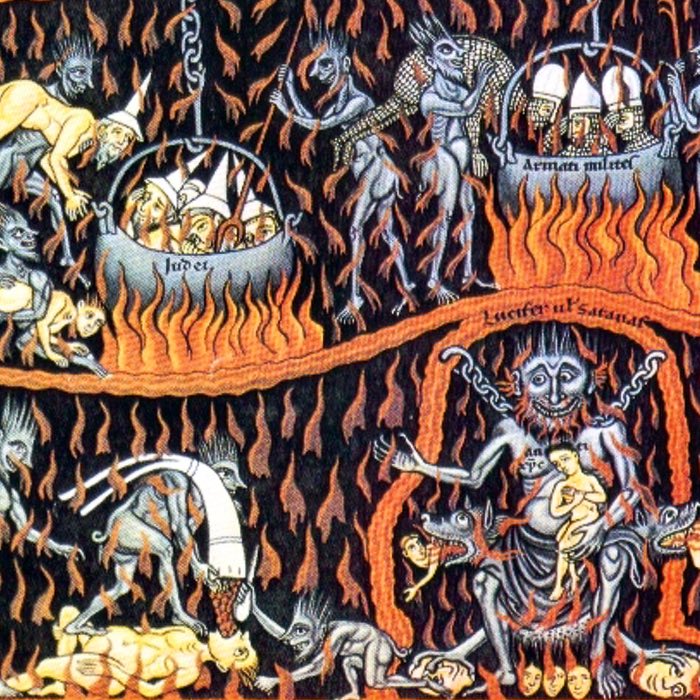

The Gospels do not present the teachings of Jesus as an exclusive or dogmatic claim to absolute truth. Instead, they emphasize personal responsibility, love, and compassion. The focus is on ethical living and inner transformation, offering a spiritual path that is inclusive rather than exclusionary. The absence of any claim to exclusive truth suggests a broader spiritual vision open to individuals of diverse beliefs and backgrounds. The concept of “holding the truth” is something, that came later with the institutionalization of Christianity – along with all the catastrophic consequences that came with it.

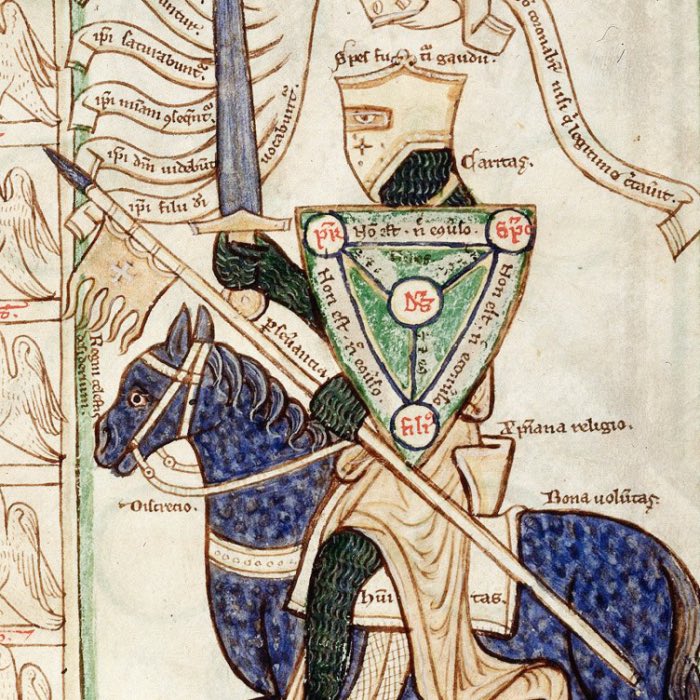

No endorsement of institutional authority

There is no direct endorsement of an institutionalized Church wielding exclusive spiritual authority. The emphasis in the Gospel message is on personal faith and community rather than centralized control or hierarchy. This absence contrasts sharply with later ecclesiastical developments, where institutional authority became a dominant feature of organized Christianity.

No need for intermediaries or hierarchies

The Gospels advocate for a direct relationship with God, without requiring hierarchical intermediaries, as, for instance, in the concept of apostolic succession. This challenges the later institutionalization of religion, where clergy and religious leaders often positioned themselves as necessary mediators between individuals and the divine. The tendency hierarchization is already evident in the Didache, a Christian text from the 1st century, which outlines guidelines for church order and leadership. The absence of hierarchical mediation emphasizes a personal and accessible spirituality.

Minimal emphasis on rituals

While some practices like prayer are emphasized, there is no insistence on rigid ritualistic observance. The emphasis is on the sincerity of faith and the authenticity of one’s actions, rather than on outward displays of religiosity. This minimal focus on ritual suggests a form of spirituality grounded in personal conviction rather than ritual compliance.

No requirement for dogmas

The Gospels focus on ethical living and personal transformation rather than adherence to fixed doctrinal systems. This contrasts with later developments in Christianity, where adherence to specific creeds and dogmas became central to religious identity. The absence of dogmatic requirements highlights the flexibility and universality of the ethical message conveyed in these narratives.

Rejection of violence, exclusion, and judgment

The teachings attributed to Jesus explicitly reject violence, promote peace, and call for inclusion and forgiveness. There is a consistent message of rejecting retaliation and embracing compassion, even towards one’s enemies. The narratives advocate for a radical form of love that transcends divisions and fosters reconciliation. This rejection of violence and exclusion underscores a commitment to universal compassion and understanding.

Were Christian core teachings unique?

The ethical and spiritual teachings attributed to Jesus, as presented in the Gospels, often appear radical and transformative. However, a closer examination of the cultural and philosophical landscape of the ancient world reveals that many of these ideas were not without precedent. Universal love, humility, forgiveness, and non-violence were themes that resonated within various traditions, suggesting that the teachings attributed to Jesus were not necessarily unique inventions but part of a broader, interconnected web of ethical thought.

Pre-Christian influences and parallels

Jewish tradition

The foundation of many of Jesus’s teachings lies firmly within the Jewish tradition. Concepts such as loving one’s neighbor (Leviticus 19:18), caring for the marginalized (Deuteronomy 10:18-19), and the pursuit of justice (Micah 6:8) were central to Jewish law and prophetic literature. The ethical principles espoused in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7), such as mercy, humility, and peacemaking, align closely with the wisdom traditions of the Hebrew Bible. Far from being a departure, Jesus’s message can be seen as a reinterpretation or intensification of Jewish ethical norms, tailored to the social and political context of his time. Which is not surprising, as Christianity emerged from a Jewish context – Christianity was and is actually Jewish in its core in my opinion.

Greco-Roman philosophy

The Hellenistic world was rich in philosophical traditions that echoed key elements of Jesus’s teachings. Stoicism, for example, emphasized universal brotherhood and the idea of living in accordance with nature, which included rationality and virtue as guiding principles. The Stoic concept of oikeiosis — the process of recognizing one’s connections to others and extending care to all humanity — bears a striking resemblance to the Gospel’s call for universal love and compassion. Similarly, Cynic philosophers advocated for simplicity, detachment from material wealth, and a rejection of societal norms, themes that are prominent in the Gospel narratives.

Independent invention or cultural synthesis?

While it is difficult to determine whether the authors of the Jesus narrative and the associated teachings were directly influenced by these pre-existing traditions, the similarities suggest a shared cultural milieu in which these ideas were independently or simultaneously developed. It is possible that the teachings attributed to the figure of Jesus emerged as a synthesis of Jewish and Hellenistic ethical thought, drawing on familiar themes but presenting them in a way that resonated with the specific needs and aspirations of the early Christian communities.

For instance, the radical emphasis on loving one’s enemies (Matthew 5:44) and turning the other cheek (Matthew 5:39) may have built upon existing ethical norms but pushed them into a realm of moral universalism that was both challenging and transformative. These teachings may represent an intensification of existing ideals rather than a wholly novel invention.

Conclusion

The teachings transmitted through the Gospel figure of Jesus present a universal framework for ethical and spiritual life, transcending religious boundaries and resonating across cultures. They call for a transformation of the heart and mind, moving beyond external rituals to focus on inner alignment with the divine.

This vision offers a timeless and dynamic path for individuals seeking moral integrity and spiritual growth. By living according to these principles, one engages in a faith that is deeply personal, universally relevant, and transformative — free from the constraints of institutional mediation – and even without requiring the existence of a historical Jesus.

References and further reading

- Crossan, J. D., The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant, 1993, HarperOne, ISBN: 978-0060616298

- Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus – Apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium, 1999, Oxford University Press on Demand, ISBN: 9780195124736

- Wright, N. T. Simply Jesus: A New Vision of Who He Was, What He Did, and Why He Matters. 2018, HarperOne, ISBN: 978-0062084408

- Borg, Marcus J. Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time: The Historical Jesus and the Heart of Contemporary Faith. 2015, HarperOne, ISBN: 978-0060609177

- Sanders, E. P., The Historical Figure of Jesus, 1996, Penguin Books, ISBN: 978-0140144994

- Pagels, Elaine, The Gnostic Gospels, 2006, W&N, ISBN: 978-0753821145 Richard Carrier, *On the historicity of Jesus – Why we might have reason for doubt, 2014, Sheffield Phoenix Press, ISBN: 9781909697492

comments