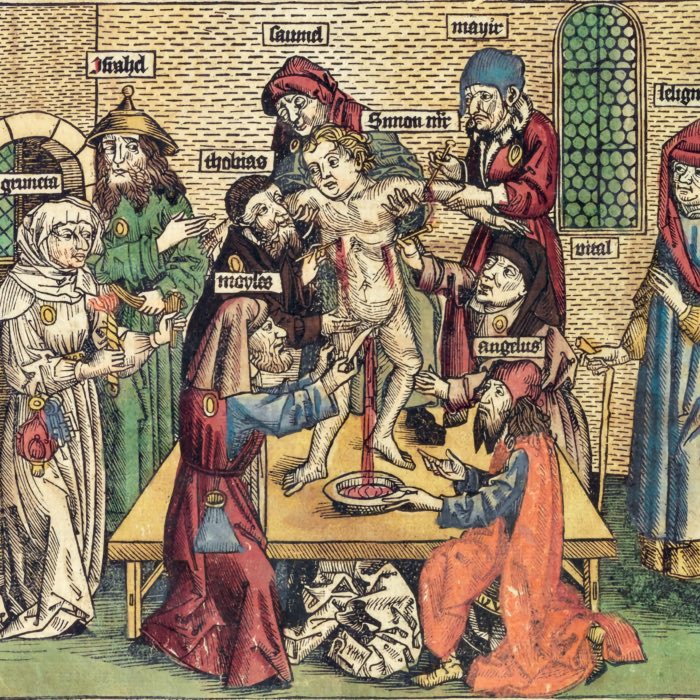

The role of sacrificial blood rituals in Judaism and its reinterpretation in Christianity

Blood sacrifice holds a profound and complex role within the context of Jewish religious tradition, reflecting both its ancient cultural origins and its theological evolution. This symbolism extends into the early Christian reinterpretation of sacrificial practices, culminating in the belief in Jesus’ sacrificial death. In this post, we take a closer look at these practices within their historical and cosmological frameworks ti better understand why blood sacrifice was seen as essential and how it became a central theme in the development of Christianity – whether Jesus is viewed as a historical figure or a “celestial construct”.

The scapegoat, William Holman Hunt, 1854. Goats were used as sin offerings in ancient Jewish sacrificial practices, i.e., in the early Yom Kippur ritual. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Blood sacrifice in Jewish tradition: Symbolism and function

In Jewish culture, blood sacrifices were integral to maintaining a covenantal relationship with YHWH (Leviticus 17:11). The Torah, particularly in the Pentateuch, outlines detailed sacrificial practices to atone for sins (Leviticus 16:15-16), purify individuals, and uphold divine law. Blood, perceived as the life force (Deuteronomy 12:23), was seen as a potent medium for sanctification and atonement. This belief finds its roots in ancient Near Eastern traditions, where sacrificial blood was thought to carry magical and purifying properties.

The first blood sacrifice: Abraham and Isaac

The story of Abraham and Isaac (Genesis 22:1-19) provides a foundational example of the theological and symbolic significance of blood sacrifice in Jewish culture. When YHWH commanded Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac, the act was intended as a demonstration of ultimate obedience and trust in YHWH. At the last moment, YHWH intervened, providing a ram as a substitute. This narrative not only established the principle of substitutionary sacrifice but also hinted at the notion that human sacrifice, while ultimately rejected, carried immense symbolic weight. The substitution of an animal for Isaac foreshadowed later theological interpretations of sacrificial acts, particularly within Christianity.

Yom Kippur and the ritual of atonement

The annual Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur, during the Second Temple period, involved elaborate rituals performed by the high priest to cleanse the sins of the community. Central to these rituals was the sacrifice of animals, with their blood symbolically purifying the altar and the people (Leviticus 16:15-16). However, the atonement achieved through these sacrifices was understood to be temporary, necessitating repetition each year. This practice reflected the belief in the finite power of animal blood to effect spiritual transformation.

Scapegoat ceremony depicted at Lincoln Cathedral in stained glass: “[Aaron] is to take the two goats and present them before the Lord at the entrance to the tent of meeting. He is to cast lots for the two goats—one lot for the Lord and the other for the scapegoat.” (Leviticus 16:7–8). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

In contemporary Jewish practice, following the destruction of the Second Temple, Yom Kippur has evolved into a day of fasting, prayer, and repentance, focusing on personal and communal reflection rather than ritual sacrifice. This shift marks a significant transformation in how atonement is understood and practiced within Judaism, while the symbolic themes of Yom Kippur influenced Christian theology, particularly in its interpretation of Jesus’ death as a once-for-all atonement.

Christian innovation: The ultimate sacrifice

When Christianity emerged, it reinterpreted Jewish sacrificial practices through the lens of its own theological and cosmological framework. The Book of Hebrews provides a detailed theological justification for this shift, arguing that Jesus’ death served as a once-for-all sacrifice that replaced the repetitive animal sacrifices of the temple. Unlike the annual Yom Kippur sacrifices, which had to be repeated every year because of their limited efficacy, Jesus’ sacrifice was portrayed as infinite in power and eternal in duration. Hebrews 9:12 explicitly states

“He entered once for all into the holy places, not by means of the blood of goats and calves but by means of his own blood, thus securing an eternal redemption.”

Ancient Jewish thought held that the potency of sacrificial blood was proportional to the value of the life offered. The blood of an animal, while effective, was inherently weaker than human blood, as indicated in the logic of Yom Kippur. If human blood was stronger, then the ultimate potency would lie in the blood of a being of divine origin. Christianity extrapolated this to present Jesus, as the “Son of God”, as the source of the most powerful and eternal blood sacrifice.

Weingartener Heilig-Blut-Tafel, 1489, showing Christ’s side pierced by a lance by Longinus, drawing blood. This is a common motif in Christian art, symbolizing the blood of Christ as a source of redemption and salvation. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Hebrews 9:13-14 draws a direct comparison between the annual animal sacrifices and Jesus’ sacrifice, arguing that the latter, offered in the heavenly temple, was infinitely more efficacious. By entering the heavenly realm and offering his own blood, Jesus achieved eternal atonement for humanity’s sins. This sacrifice, unlike the limited efficacy of animal sacrifices, required no repetition.

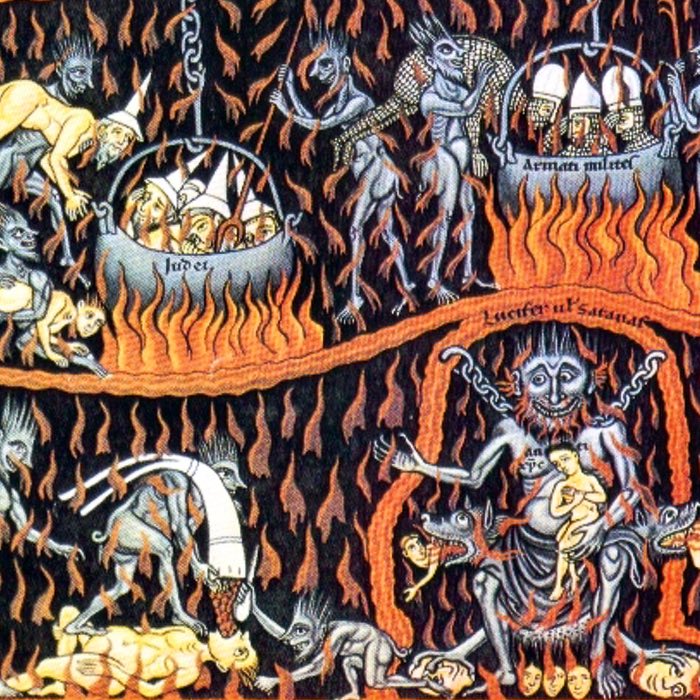

Christian theology also adapted this framework to address the problem of sin and Satan’s corruption of creation. In the cosmological worldview inherited from Second Temple Judaism, the material world was often seen as a domain corrupted by Satan and his fallen angels, who introduced death and sin into creation (Genesis 3; Book of Enoch). This apocalyptic perspective framed the earthly realm as a battleground for spiritual forces. Jesus’ sacrificial death was interpreted as a decisive act to break Satan’s hold over humanity and the lower realms of existence, redefined as a singular, cosmic event, contrasting with the repetitive nature of temple sacrifices outlined in Leviticus 16.

Non-canonical texts, such as the Ascension of Isaiah and the Book of Jubilees, expand on this cosmology by describing a multi-layered universe where heavenly realities parallel and surpass earthly ones. These texts underscore the belief that sacrifices performed on earth were not merely symbolic but part of a cosmic framework connecting the divine and human realms. By positioning Jesus as both the ultimate high priest and the sacrificial victim, Christianity not only superseded the temple cult but also universalized the act of redemption, making it accessible to all humanity.

The revolutionary idea behind the Christian reinterpretation

The redefinition of sacrificial blood rituals extended beyond atonement to the very concept of the temple itself. In Christianity, the temple was no longer a physical, centralized structure but rather the collective body of believers, as expressed in Paul’s assertion (1 Corinthians 3:16-17):

“Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you?”

This radical idea democratized access to the divine, removing the necessity for intermediaries or institutional control and positioning each believer as a locus of sacredness.

This reimagining of sacred space carried significant implications, directly stemming from the shift in the sacrificial and temple paradigms. By declaring each believer a temple where God’s Spirit resides, Christianity embraced an egalitarian ideal that granted all individuals direct access to YHWH. This concept fundamentally challenged the centralized, hierarchical structure of the Jewish temple and its priesthood, as well as the broader cultural norms of mediated religious experience. However, this revolutionary idea faced limitations as Christianity became institutionalized, with the emergence of formal ecclesiastical authority and a renewed emphasis on hierarchical mediation through bishops, priests, and sacraments. This shift reflected a tension between the democratizing vision of the early movement and the practical realities of maintaining governance and orthodoxy within a rapidly expanding religious community. Hierarchical structures and formal ecclesiastical authority emerged, reintroducing mediation and centralized control. While the early Christian notion of the believer-as-temple remains a cornerstone of Christian theology, its practical application was framed within the evolving context of organized religion, reflecting a tension between the democratizing vision of the early movement and the realities of institutional governance.

Symbolism and legacy

The symbolism of Jesus as the ultimate sacrifice carried profound theological and cultural implications, uniting key elements of Jewish tradition and Christian reinterpretation into a transformative religious vision:

- Abolition of the temple cult

By presenting Jesus’ death as the ultimate atonement, Christianity rendered the temple sacrificial system unnecessary. This paved the way for a faith that could transcend the physical temple and expand beyond Jewish communities. The temple sacrifices, central to the covenantal relationship in Judaism, were replaced by the concept of a universal and eternal atonement, as symbolized by Jesus’ sacrifice. - The new covenant

Jesus’ blood was seen as inaugurating a new covenant between YHWH and humanity, one that was eternal and inclusive. This marked a significant departure from the older, conditional covenants based on adherence to the Torah. As described in Hebrews 9:15:“For this reason Christ is the mediator of a new covenant, that those who are called may receive the promised eternal inheritance.”

- Universal atonement

Jewish sacrifices traditionally focused on the collective sins of the Israelite community. Jesus’ sacrifice redefined this framework, presenting atonement as universal and extending salvation to all humanity. This universal scope is reflected in passages like Hebrews 10:10:“We have been made holy through the sacrifice of the body of Jesus Christ once for all.”

- The Eucharist and drinking the blood of Christ

This theological shift also directly influenced the Christian ritual of the Eucharist, where believers consume bread and wine representing the body and blood of Christ (Matthew 26:26-28). The wine, identified as Christ’s blood, signifies participation in his sacrificial death and the new covenant established through it. To a certain extent, the symbolism of the Eucharist, therefore, serves as a theological bridge between the Jewish understanding of blood’s sacred power and the Christian reimagining of it as a means of universal redemption.

The drastic reinterpretation of blood sacrifice in Christianity, from a ritualistic practice to a cosmic event of universal significance, reflects the revolutionary attempts of early Christianity. By redefining the temple, the priesthood, and the sacrificial system, Christianity pave the way of Judaism liberated from the constraints of the temple cult and its corruption at that time. By examining the origins and evolution of this sacrificial symbolism, we are able to trace the complex interplay between Jewish tradition and Christian innovation, shedding some light on the theological and cultural transformations that shaped the early Christian movement.

References and further reading

- Richar Carrier, Jesus from outer space: What the earliest Christians really believed about Christ, 2020, Pitchstone Publishing, ISBN: 978-1634311946

- Richard Carrier, On the historicity of Jesus – Why we might have reason for doubt, 2014, Sheffield Phoenix Press, ISBN: 9781909697492

- “Jesus from Outer Space with Dr. Richard Carrier”, YouTubeꜛ, 27.03.2021

comments