How Jesus became God: Exploring Bart D. Ehrman’s thesis on the development of Christian belief in Jesus’s divinity

Bart D. Ehrman’s How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee offers a meticulously researched account of how early Christians came to view Jesus as divine. Ehrman’s work traces the evolution of Jesus’s divinity from a historical Jewish preacher to a figure exalted by his followers after his death, culminating in the formalization of his divine status in the 4th century. While Ehrman argues for a historical Jesus who was gradually deified, Richard Carrier, a leading proponent of the mythicist position, rejects the idea of a historical Jesus altogether. Carrier posits that Jesus was originally conceived as a celestial figure whose story was later euhemerized — that is, placed into a historical narrative. In this post, we examine Ehrman’s thesis in light of Carrier’s theories, exploring how both perspectives illuminate the complex development of early Christian belief.

Roof fresco of Christ Pantocrator, Nativity of the Theotokos Church, Bitola, North Macedonia. The Pantocrator is a common iconographic depiction of Christ in Eastern Orthodox Christianity, emphasizing his role as the ruler of the universe. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Ehrman’s historical Jesus and early beliefs

Ehrman contends that during his lifetime, Jesus was neither viewed as divine by himself nor by his followers. Instead, he situates Jesus firmly within the Jewish apocalyptic tradition, portraying him as a charismatic preacher who anticipated the imminent arrival of God’s Kingdom. According to Ehrman, Jesus’s message focused on repentance and preparation for divine intervention.

In Second Temple Judaism, strict monotheism prevailed, leaving little conceptual room for a human figure to be considered divine. Ehrman argues that Jesus’s followers likely saw him as a prophet or the Messiah — roles of great significance but not implying divinity. Importantly, Ehrman asserts that Jesus himself did not claim to be God, but rather an eschatological figure heralding the Kingdom of God.

Carrier, on the other hand, argues that this entire narrative is a later historical construction. In his book On the Historicity of Jesus, Carrier suggests that Jesus began as a purely mythical figure, akin to other celestial savior deities in the ancient Mediterranean world. According to Carrier, early Christians initially worshiped a heavenly Jesus who revealed divine truths through visions and scriptural interpretation, only later situating him in a historical context through the process of euhemerization.

The role of the resurrection in shaping belief

For Ehrman, the pivotal event that transformed Jesus’s identity in the eyes of his followers was his resurrection. After Jesus’s crucifixion — a humiliating and seemingly definitive end to his mission — his followers claimed to have experienced him alive again. Ehrman argues that these resurrection experiences led the disciples to reinterpret Jesus’s life and death in light of Jewish eschatological expectations, eventually seeing him as exalted by God.

Initially, Ehrman explains, the resurrection was understood not as proof of Jesus’s inherent divinity but as evidence of his exaltation to a divine status. Drawing on Jewish traditions of exalted figures like Enoch and Elijah, early Christians came to view Jesus as a human who had been uniquely vindicated and elevated by God.

Carrier offers a different interpretation: he posits that the resurrection was part of a pre-existing mythic framework in which dying-and-rising gods played a central role. In this context, the resurrection story was not a historical event but a symbolic narrative reflecting common mythological themes of death, rebirth, and triumph over chaos. According to Carrier, Paul’s writings — the earliest Christian texts — depict a celestial Jesus who was crucified and resurrected in a heavenly realm, not on Earth. This interpretation aligns with broader ancient mythic traditions, such as those involving Osiris, Tammuz, and Mithras.

The gradual development of Christology

Ehrman describes a gradual evolution from early exaltation Christologies — where Jesus was seen as a human exalted to divine status after his resurrection — to incarnational Christologies, which posited that Jesus was a preexistent divine being who became human. This development, Ehrman argues, was influenced by Greco-Roman religious thought, where distinctions between humanity and divinity were more fluid.

Carrier similarly acknowledges the influence of Hellenistic religious ideas but frames the process differently. Rather than a historical figure being exalted posthumously, Carrier argues that early Christians, inspired by Jewish apocalypticism and Hellenistic mystery cults, initially envisioned Jesus as a celestial being. Over time, as Christianity spread and sought legitimacy within the Roman Empire, the mythic figure of Jesus was historicized to ground the faith in a concrete past.

Both scholars agree that by the time of Paul’s letters, some Christians already regarded Jesus as a divine figure. Ehrman emphasizes the diversity of early beliefs about Jesus’s nature, noting that Paul’s writings present Jesus as preexistent and exalted, but without fully equating him with God the Father. Carrier, however, interprets Paul’s depiction of Jesus as consistent with a mythic savior archetype rather than a historical person.

The fourth-century shift: From diversity to orthodoxy

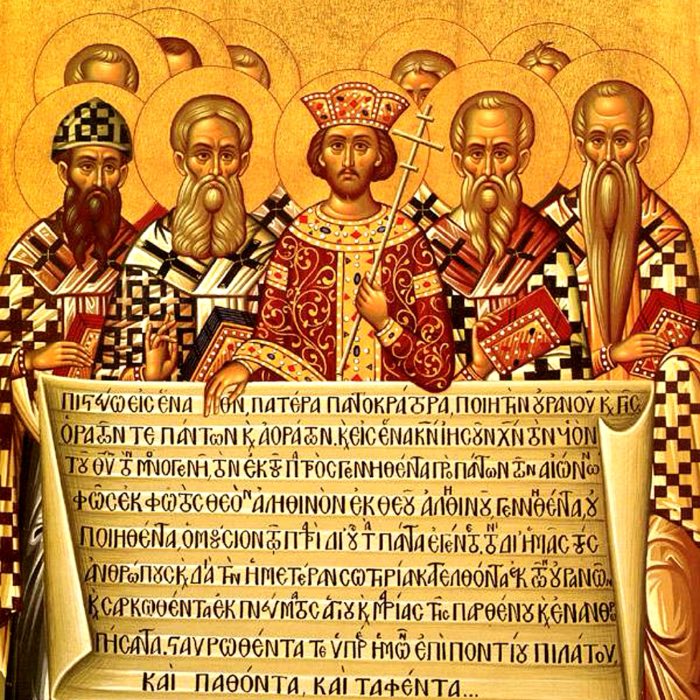

Ehrman highlights the Council of Nicaea in 325 as a critical turning point in the development of Christian doctrine. Convened by Emperor Constantine, the council declared Jesus to be homoousios (of the same substance) with God the Father, establishing the foundation for the doctrine of the Trinity. Ehrman underscores that the Nicene Creed represented a significant departure from the diverse Christological views of earlier centuries.

Carrier views this doctrinal consolidation as part of a broader pattern in which religious movements evolve from diverse, competing sects into centralized institutions with rigid orthodoxy. In his view, the formalization of Jesus’s divinity and the development of the Trinity doctrine were strategies employed by the institutional Church to solidify its authority and marginalize alternative interpretations.

Euhemerization and the mythicist perspective

A key element of Carrier’s thesis is the concept of euhemerization — the process by which a mythic or celestial figure is transformed into a historical person. Carrier argues that this process was common in ancient religions, where gods and heroes were often historicized to lend credibility to religious movements. He posits that early Christians engaged in a similar process with Jesus, constructing a historical narrative around a pre-existing celestial savior figure.

While Ehrman does not adopt the mythicist position, his acknowledgment of the diversity of early Christian beliefs and the gradual development of doctrine provides a framework in which Carrier’s theory can be considered. Both scholars highlight the role of socio-political factors in shaping Christian orthodoxy, though they differ in their conclusions about Jesus’s historicity.

Implications of Ehrman and Carrier’s theories

Ehrman’s thesis challenges traditional Christian narratives by emphasizing the historical processes through which Jesus’s divinity was constructed. His work underscores the contingent nature of theological doctrines, highlighting how beliefs often presented as eternal truths emerged through complex interactions between religious ideas, cultural contexts, and institutional power.

Carrier’s mythicist perspective goes further, rejecting the premise of a historical Jesus altogether and framing early Christianity as a syncretic religious movement that combined Jewish apocalypticism with Hellenistic mystery cult motifs. His theory invites a re-evaluation of early Christian history, emphasizing the myth-making processes at its core.

Together, Ehrman and Carrier offer complementary yet distinct insights into the origins of Christian belief. While Ehrman provides a detailed account of how Jesus came to be seen as God within a historical framework, Carrier highlights the mythological and constructed nature of this process, calling into question the very existence of Jesus as a historical figure.

Critiques and responses

Ehrman’s theory in How Jesus Became God has been subject to criticism from various scholars and theologians. These critiques come from a range of perspectives, including those who advocate for traditional Christian beliefs, scholars with differing historical methodologies, and even some who generally agree with Ehrman but question certain aspects of his argument or evidence. Below are some key points of criticism:

Traditionalist critiques: Defense of orthodoxy

Many scholars and theologians aligned with traditional Christian beliefs critique Ehrman’s assertion that Jesus did not claim divinity and that his earliest followers did not view him as divine.

Critics argue that certain New Testament texts, such as Jesus’s “I am” statements in the Gospel of John (e.g., John 8:58), clearly indicate that Jesus understood himself as divine. Ehrman contends that these are later theological developments and not historical accounts of Jesus’s words. However, traditionalists argue that such statements align with Jewish Messianic expectations and demonstrate an early belief in Jesus’s divine identity.

Scholars like Richard Bauckham (author of Jesus and the God of Israel) and Larry Hurtado (Lord Jesus Christ) maintain that a high Christology — understanding Jesus as divine — was present from the very earliest stages of the Christian movement. They cite the worship of Jesus in early Christian communities, evident in hymns like Philippians 2:6–11, as evidence of an early belief in his preexistence and divinity, contradicting Ehrman’s claim that these views developed later.

Overemphasis on Greco-Roman influence

Ehrman emphasizes the influence of Greco-Roman religious thought, such as the deification of emperors and Hellenistic hero cults, on the development of Christian beliefs about Jesus’s divinity. Critics argue that this framework underestimates the Jewish context of early Christianity.

Scholars like N. T. Wright (The Resurrection of the Son of God) argue that early Christian beliefs about Jesus’s exaltation and divinity were deeply rooted in Jewish apocalyptic and Messianic traditions, rather than being heavily influenced by Greco-Roman ideas. Wright contends that Jewish concepts of divine agency, such as the role of figures like Wisdom or the Angel of the Lord, provided a framework for early Christians to view Jesus as both distinct from and unified with God.

Critics suggest that Ehrman does not fully address how early Christians, as devout Jews, reconciled their strict monotheism with the worship of Jesus. Traditionalists and some historians see this as a theological development rooted in Jewish thought rather than a borrowing from pagan traditions.

Historical methodology and use of sources

Ehrman’s historical methodology has also been questioned, particularly his reliance on textual sources and interpretations that some view as overly speculative or selective.

Some critics argue that Ehrman gives too much weight to later developments, such as the Gospel of John or second-century Christological debates, while underemphasizing earlier sources like Paul’s letters. They contend that Paul’s writings, which contain high Christology, suggest a divine understanding of Jesus within a few decades of his death.

While Ehrman focuses on the resurrection as the key turning point in the development of Jesus’s divinity, critics argue that his explanations for the disciples’ belief in the resurrection (e.g., visions, psychological experiences) are speculative and lack empirical support. These critics suggest that Ehrman downplays the transformative impact that such experiences had on the early Christian movement.

Simplification of early Christological diversity

Ehrman highlights the diversity of early Christian beliefs about Jesus, arguing that the process of doctrinal consolidation into Nicene orthodoxy marginalized alternative views. Some critics believe Ehrman oversimplifies this diversity.

While it is true that early Christianity included a range of Christological views, some critics argue that Ehrman exaggerates the degree of disunity. They point out that even among diverse groups, a consistent theme of Jesus’s exalted status and central role in salvation exists, suggesting more continuity than Ehrman acknowledges.

Critics also argue that Ehrman does not give sufficient attention to the dominance of proto-orthodox views in early Christian communities, which laid the groundwork for Nicene theology. While heretical views like adoptionism or docetism existed, proto-orthodox beliefs appear to have been widespread from an early stage.

Mythicist critique: The problem of assuming historicity

From a mythicist perspective, including that of Richard Carrier, a key critique of Ehrman’s thesis is that it presupposes the existence of a historical Jesus. Mythicists argue that Ehrman’s entire framework — tracing how Jesus became understood as divine — overlooks the possibility that Jesus began as a purely celestial figure. Carrier contends that the early belief in Jesus’s divinity did not develop from the exaltation of a human preacher but rather emerged from visionary experiences and reinterpretations of Jewish scriptures, portraying Jesus as a heavenly being.

In this view, the resurrection narratives are mythological constructs that served to euhemerize a celestial savior figure, placing him into a historical context. Ehrman’s failure to engage with this possibility leaves a significant gap in his analysis, according to mythicist scholars.

Worship practices and mythic origins

Larry Hurtado’s emphasis on early Christian worship practices as evidence of high Christology is also critiqued by mythicists. While Hurtado argues that such worship indicates early belief in Jesus’s divinity, Carrier and other mythicists suggest that worship of celestial beings was not uncommon in Second Temple Judaism. They propose that early Christians worshipped Jesus as a heavenly intermediary, similar to other exalted figures in Jewish thought, without necessitating a historical incarnation.

Engagement with alternative theories

Richard Bauckham and others propose that early Christians viewed Jesus as part of God’s unique divine identity rather than as a separate deity. This theory challenges Ehrman’s assertion that belief in Jesus’s divinity was heavily influenced by pagan ideas.

Carrier, however, counters that such views reflect later theological developments rather than the original mythicist framework of early Christianity. He emphasizes that the diversity of early Christian belief, including adoptionist and docetic views, supports the idea of a gradual evolution of a mythic figure into a historicized one.

A balanced view of Ehrman’s thesis

Bart D. Ehrman’s How Jesus Became God has made a significant contribution to the study of early Christianity, offering a compelling narrative of how belief in Jesus’s divinity evolved over time. His emphasis on historical context and the gradual development of Christology challenges traditional understandings and provides a valuable framework for understanding the diversity of early Christian thought.

However, his thesis is not without its critics. Questions about his interpretation of sources, his emphasis on Greco-Roman influences over Jewish contexts, and his dismissal of the supernatural dimensions of Christian theology highlight the complexities and debates inherent in this field. Additionally, mythicist critiques underscore the importance of questioning the historicity of Jesus altogether, suggesting that Ehrman’s thesis may overlook the fundamentally mythological origins of early Christian belief. While Ehrman’s work invites us to view Christian doctrine through a historical lens, it also underscores the importance of engaging with alternative perspectives to gain a fuller understanding of the origins of Christian belief.

Conclusion

The development of belief in Jesus’s divinity was a complex and multifaceted process shaped by theological reflection, cultural influences, and socio-political dynamics. Bart D. Ehrman’s How Jesus Became God traces this evolution from a historical perspective, emphasizing the gradual exaltation of Jesus by his followers. Richard Carrier’s mythicist theory, by contrast, posits that Jesus began as a celestial figure whose story was later historicized.

While Ehrman and Carrier diverge on the question of Jesus’s historicity, their analyses converge in highlighting the constructed nature of early Christian doctrine. By examining the historical and mythological dimensions of Jesus’s divinity, both scholars invite us to reconsider how religious beliefs are formed, propagated, and institutionalized.

References and further reading

- Bart D. Ehrman, How Jesus became God – The exaltation of a Jewish preacher from Galilee, 2014, Harper Collins, ISBN: 9780062252197

- Richard Carrier, On the historicity of Jesus – Why we might have reason for doubt, 2014, Sheffield Phoenix Press, ISBN: 9781909697492

- Richar Carrier, Jesus from outer space: What the earliest Christians really believed about Christ, 2020, Pitchstone Publishing, ISBN: 978-1634311946

- Hurtado, L. W., Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity, 2005, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co, ISBN: 978-0802831675

- Dunn, James D. G., Christology in the making: An inquiry into the origins of the doctrine of the incarnation, 2003, SCM Press, ISBN: 978-0334029298

- Casey, Maurice, Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian’s Account of His Life and Teaching, 2010, T&T Clark, ISBN: 978-0567645173

- Brown, R. E., An Introduction to New Testament Christology, 1994 Paulist Press, ISBN: 978-0809135165

comments