Twelve Apostles, one myth: Debunking the foundation of institutional Christianity

The figure of Jesus in the Gospels is considered, according to Richard Carrier’s mythicist theory, to be an invented mythological character developed by early Christian communities. If Jesus himself is a mythic construct rather than a historical person, the narrative of the twelve apostles must similarly be viewed through a symbolic and theological lens rather than as a literal account of historical events. This perspective challenges the foundational claims of apostolic succession and institutional authority within the Church and underscores the core message of personal spiritual transformation, rather than a dependence on institutionalized mediation. In this post, we take a closer look at the mythicist critique of the twelve apostles and its implications for both the institutional Church and the personal Christian faith.

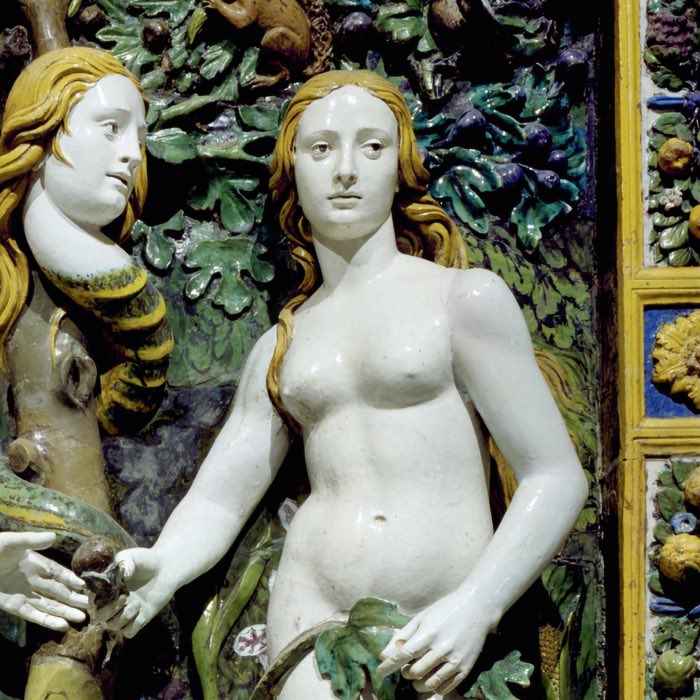

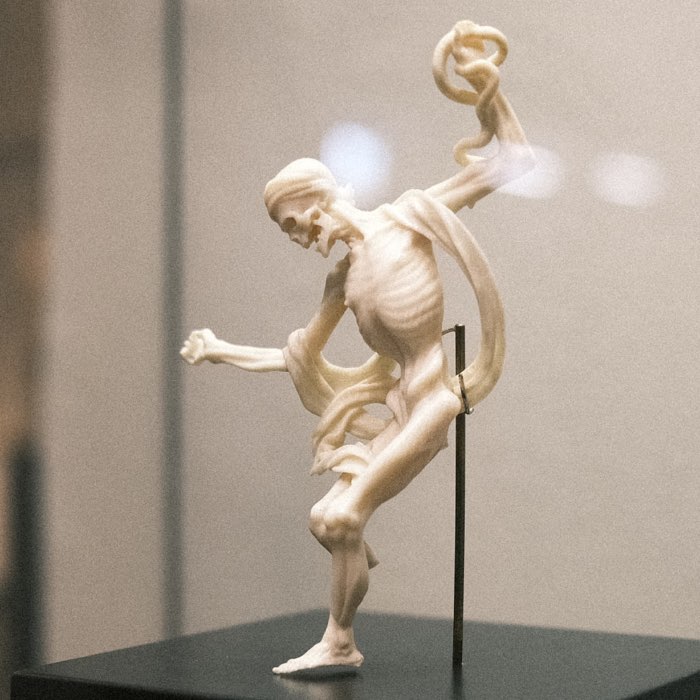

The Communion of the Apostles, Luca Signorelli, 1512. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The symbolic role of the twelve apostles in early Christian narratives

Within Jewish tradition, the number twelve holds profound symbolic significance. The twelve tribes of Israel, descended from the twelve sons of Jacob, represent the entirety of the Jewish people and their covenant with YHWH. The early Christians, seeking to establish their movement as the fulfillment of Jewish prophecy and the legitimate continuation of YHWH’s covenant, likely adopted the motif of twelve followers for Jesus to evoke this symbolic completeness.

Carrier argues that the twelve apostles, as depicted in the Gospels, were not historical individuals but narrative devices created to convey theological ideas. By aligning Jesus with a group of twelve close disciples, the early Christian authors could signal that Jesus’ mission was to establish a new covenant encompassing all of YHWH’s people, just as the twelve tribes represented the original covenant. This symbolic use of the number twelve provided a sense of continuity with Jewish tradition while positioning Christianity as a distinct and divinely ordained movement.

The variation in the lists of the twelve apostles across the Gospels and Acts further supports the idea that the apostles were not fixed historical figures but flexible symbols adapted for different narrative purposes. For example, the names of some apostles differ between the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) and John’s Gospel, suggesting that the composition of the group was not based on an established historical memory but rather on theological and literary considerations.

Apostolic succession and the question of institutional authority

One of the central claims of the institutional Church, particularly in Catholic and Orthodox traditions, is the doctrine of apostolic succession. This doctrine asserts that the authority of bishops and priests derives directly from the original apostles, who were commissioned by Jesus himself. The Church claims that through an unbroken line of ordination, this apostolic authority has been transmitted across generations, granting the clergy a unique role as mediators of divine grace and interpreters of sacred truth.

If, however, the twelve apostles were mythological constructs rather than historical figures, the foundation of apostolic succession becomes highly questionable. Without a historical group of apostles directly appointed by Jesus, the legitimacy of the Church’s hierarchical structure – already visible in early Christian writings like the Didache, which outlines instructions for appointing bishops and deacons – and its claim to exclusive spiritual authority are undermined. The doctrine of apostolic succession, rooted in the narrative of the Gospels, appears instead as a later institutional development designed to consolidate power and control over Christian communities.

Carrier’s perspective invites a re-evaluation of the role of clergy and the nature of religious authority. If the apostles were symbolic figures representing the spread of Jesus’ message, rather than literal founders of a hierarchical institution, the emphasis shifts from institutional authority to personal spiritual responsibility. The Church’s claim to be the sole custodian of salvation and divine truth becomes untenable, opening the door to a more decentralized and individual approach to faith.

The core message of the Gospels: A personal path to spiritual transformation

The teachings attributed to Jesus in the Gospels emphasize personal spiritual transformation, ethical living, and direct communion with the divine. The core message focuses on values such as love, compassion, humility, forgiveness, and inner moral integrity. Notably absent from these teachings is any explicit requirement for institutional mediation, elaborate rituals, or rigid dogmas.

In Luke 17:21, Jesus is quoted as saying, “The Kingdom of God is within you,” suggesting that spiritual growth and salvation are matters of personal inner transformation rather than external institutional validation. The Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5–7) presents a vision of righteousness centered on the heart’s intentions and ethical behavior, rather than on adherence to ritualistic practices or clerical authority.

Carrier’s critique of the historicity of Jesus and the apostles aligns with this understanding of the Gospel message as a personal, universal path rather than a system requiring institutional control. If the narrative of the twelve apostles was constructed to serve a symbolic purpose, then the institutional structures built upon this narrative — including the priesthood, sacramental system, and centralized ecclesiastical hierarchy — represent later developments that diverge from the original ethos of the Gospel teachings.

The rejection of ritualistic cult practices and dogmatic control

Another implication of Carrier’s mythicist perspective is the critique of the ritualistic and dogmatic elements that have come to dominate institutional Christianity. The Gospels, as narratives focused on ethical teachings and personal spirituality, do not emphasize the necessity of elaborate rituals or rigid dogmas. While certain practices, such as prayer and communal gatherings, are mentioned, they are presented in a simple and accessible manner, without the hierarchical and sacramental complexity that later characterized the Church.

The institutionalization of Christianity, particularly following its adoption as the state religion of the Roman Empire under Constantine, introduced a host of ritualistic and dogmatic requirements that were absent from the original Gospel message. The development of elaborate liturgies, mandatory creeds, and complex sacramental systems can be seen as efforts to standardize belief and practice, thereby consolidating the Church’s authority. Carrier’s theory underscores that these developments were not inherent to the message of Jesus but were products of historical and political processes aimed at establishing religious uniformity and control.

Consequences for modern Christian practice

If the narrative of the twelve apostles and the hierarchical structures built upon it are mythological constructs, modern Christian practice faces significant implications. Rather than adhering to rigid institutional frameworks and external rituals, believers might instead focus on the personal and ethical dimensions of their faith. This approach emphasizes individual responsibility, direct engagement with spiritual teachings, and the cultivation of compassion, humility, and justice.

A reorientation toward the core Gospel message—stripped of later institutional accretions—could lead to a more inclusive and decentralized form of Christianity. Such a faith would prioritize personal spiritual growth and community support over doctrinal conformity and clerical authority. In this model, the role of religious leaders would shift from authoritative mediators to facilitators of spiritual exploration and ethical living.

Conclusion

The mythicist critique of the twelve apostles as symbolic rather than historical figures invites a profound rethinking of Christian origins and institutional authority. Carrier’s theory challenges the traditional narrative of apostolic succession and the legitimacy of hierarchical Church structures, suggesting that the original Gospel message was one of personal spiritual transformation rather than institutional control.

By recognizing the symbolic and constructed nature of the apostolic narrative, believers are encouraged to engage directly with the ethical and spiritual teachings attributed to Jesus. This approach offers a vision of faith that is personal, inclusive, and transformative, free from the constraints of institutional mediation and ritualistic cult practices. In doing so, it returns to the essence of the Gospel message — a call to live with love, humility, and compassion, guided not by external authority but by the inner voice of conscience and the universal quest for truth.

References and further reading

- Richar Carrier, Jesus from outer space: What the earliest Christians really believed about Christ, 2020, Pitchstone Publishing, ISBN: 978-1634311946

- Richard Carrier, On the historicity of Jesus – Why we might have reason for doubt, 2014, Sheffield Phoenix Press, ISBN: 9781909697492

- Udo Schnelle, Die ersten 100 Jahre des Christentums 30-130 n. Chr. - Die Entstehungsgeschichte einer Weltreligion, 2016, UTB, ISBN: 9783825246068

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bruce Manning Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The text of the New Testament – Its transmission, corruption, and restoration, 2005, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195166675

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 1 Die Frühzeit, 1996, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012632

comments