Why did Jewish apocalypticism culminate in the 1st century CE?

Throughout history, human societies have often grappled with the notion of an impending apocalypse — a final, cataclysmic event that would reshape or end the world as they knew it. For the Jewish people, the idea of doomsday gained prominence during their tumultuous history under foreign rule, evolving into a complex eschatological framework that would later influence Christianity. Inspired by a talk I recently watched by Richard Carrier titled “From Noah’s Flood to Rapture Dayꜛ”, this post explores the origins and development of Jewish apocalyptic beliefs, tracing their roots from Persian Zoroastrian influences to the widespread messianic fervor of the 1st century CE. We will explore how these beliefs culminated in a series of failed messianic movements and ultimately shaped the emergence of Christianity as a surviving apocalyptic sect.

The mass-revelation at Mount Horeb, illustration from a Christian Bible card published by the Providence Lithograph Company, 1907. This image depicts the biblical account of the Israelites receiving the Ten Commandments from God at Mount Sinai. The event is a pivotal moment in Jewish history, marking the establishment of the covenant between God and the Israelites. Public revelations like this one played a crucial role in shaping Jewish apocalyptic beliefs, as they reinforced the idea of divine intervention in human affairs. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Where do Jewish doomsday beliefs come from?

The origins of Jewish apocalypticism are deeply intertwined with historical influences from neighboring cultures, particularly during the Persian occupation of Israel. The dominant religion of Persia was Zoroastrianism, which introduced several key concepts that would later permeate Jewish thought:

- A cosmic battle between a good god and an evil god, symbolizing the eternal struggle of light versus darkness.

- The idea that evil individuals would be punished by burning in hell, while the righteous would await resurrection in heaven.

- A prophesied river of fire that would purify the universe, consuming even hell itself.

- The promise of a new, perfected world created by divine intervention.

- A general resurrection in which the good would be restored to life to inhabit the new world forever.

Initially, Jewish religious thought lacked these elements. However, under Persian rule, Jewish communities adopted these eschatological expectations, adapting them to their own narrative. Initially, they anticipated that God would intervene to destroy their oppressors, but when the Greeks supplanted Persian rule, the expectation shifted to a new deliverance.

The first biblical doomsday: The flood

The earliest depiction of a divine apocalypse in Jewish scripture appears in the story of Noah’s flood. According to Genesis 9:11-17, God decides to wipe out humanity through a catastrophic flood but later regrets this decision, establishing a covenant promising never to destroy the earth by water again. This narrative marks the beginning of a pattern: divine judgment followed by a promise of peace. Interestingly, this flood narrative likely originates from earlier Mesopotamian mythology, specifically the Epic of Gilgamesh, which also describes a great flood sent by the gods to destroy humanity, followed by divine regret and a covenant-like resolution.

The Deluge, Francis Danby, 1840, oil on canvas. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Yet, as time progressed, this promise was repeatedly overshadowed by new prophecies of destruction.

From flood to fire: Shifting apocalyptic visions in Jewish prophecy

Despite the covenant after the flood, later prophetic writings depict a God who continues to threaten humanity with apocalyptic destruction:

- Nahum 1:2-8

God’s wrath is described as an all-consuming fire that will dry up seas, rivers, and mountains. The passage reads:“The LORD is a jealous and avenging God; the LORD takes vengeance and is filled with wrath. The LORD takes vengeance on his foes and vents his wrath against his enemies. The LORD is slow to anger but great in power; the LORD will not leave the guilty unpunished. His way is in the whirlwind and the storm, and clouds are the dust of his feet. He rebukes the sea and dries it up; he makes all the rivers run dry. Bashan and Carmel wither and the blossoms of Lebanon fade. The mountains quake before him and the hills melt away. The earth trembles at his presence, the world and all who live in it.”

- Isaiah 51:5

The heavens will vanish like smoke, and the earth will wear out like an old garment, but God’s salvation will endure forever. The verse states:“My righteousness draws near speedily, my salvation is on the way, and my arm will bring justice to the nations. The islands will look to me and wait in hope for my arm. Lift up your eyes to the heavens, look at the earth beneath; the heavens will vanish like smoke, the earth will wear out like a garment and its inhabitants die like flies. But my salvation will last forever, my righteousness will never fail.”

- Malachi 4:1-3

A day of reckoning is described, where the wicked will be burned to ash, while the righteous will experience healing and triumph. The passage declares:“Surely the day is coming; it will burn like a furnace. All the arrogant and every evildoer will be stubble, and the day that is coming will set them on fire,” says the LORD Almighty. “Not a root or a branch will be left to them. But for you who revere my name, the sun of righteousness will rise with healing in its rays. And you will go out and frolic like well-fed calves. Then you will trample on the wicked; they will be ashes under the soles of your feet on the day when I act,” says the LORD Almighty.”

- Zechariah 14:12-19

A plague will afflict those who oppose Jerusalem, with vivid imagery of rotting flesh and eyes, culminating in divine punishment for nations that refuse to worship God. The text reads:“This is the plague with which the LORD will strike all the nations that fought against Jerusalem: Their flesh will rot while they are still standing on their feet, their eyes will rot in their sockets, and their tongues will rot in their mouths. On that day people will be stricken by the LORD with great panic. They will seize each other by the hand and attack one another. Judah too will fight at Jerusalem. The wealth of all the surrounding nations will be collected — great quantities of gold and silver and clothing. A similar plague will strike the horses and mules, the camels and donkeys, and all the animals in those camps. Then the survivors from all the nations that have attacked Jerusalem will go up year after year to worship the King, the LORD Almighty, and to celebrate the Festival of Tabernacles. If any of the peoples of the earth do not go up to Jerusalem to worship the King, the LORD Almighty, they will have no rain. If the Egyptian people do not go up and take part, they will have no rain. The LORD will bring on them the plague he inflicts on the nations that do not go up to celebrate the Festival of Tabernacles. This will be the punishment of Egypt and the punishment of all the nations that do not go up to celebrate the Festival of Tabernacles.”

These passages reinforce a recurring theme: God continually revises His approach to humanity, promising destruction but also salvation for His chosen people. This apocalyptic tone created a persistent expectation among the Jewish people that they were destined for a climactic divine intervention.

Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Albrecht Dürer, woodcut, 1498. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

Messianic fever in the 1st Century CE

By the 1st century CE, there was a significant surge in individuals claiming to be the messiah. Prophetic scriptures fueled expectations that a messiah would soon arrive. Figures such as John the Baptist and Simon Magus emerged, each claiming messianic roles.

During the Jewish-Roman war, there are indications that some Jews believed initiating a war with Rome would hasten the apocalypse. Josephus, the Jewish historian, documents various messianic claimants, such as:

- Joshua (1st century BCE)

The name Joshua, later rendered as Jesus, was linked to the biblical figure who led the Israelites into Canaan. In the Hebrew Bible, Joshua is depicted as the leader who succeeded Moses and led the Israelites across the Jordan River into the Promised Land, famously bringing down the walls of Jericho. This act of divine conquest made Joshua a symbolic figure of deliverance and fulfillment of God’s promises, which later messianic claimants sought to emulate. - Theudas (mid-1st century CE)

Theudas gathered a large group of followers and claimed he could part the Jordan River, evoking imagery of Joshua (Jesus) and Moses. His actions were clearly designed to evoke the memory of Joshua and signal his own messianic authority. His movement was suppressed by the Romans, and he was beheaded. Josephus records this event. - The Egyptian (c. 50s CE)

This figure gathered thousands of followers and led them to the Mount of Olives, promising to bring down the walls of Jerusalem through divine power like Joshua did with Jericho. This act, mirroring Joshua’s conquest of Canaan, was intended to signal the fulfillment of apocalyptic prophecies and the imminent arrival of God’s kingdom. However, the Roman governor Felix dispersed the group, and the Egyptian prophet fled, never to be seen again.

Interestingly, the New Testament portrays Jesus of Nazareth as engaging in similar symbolic acts, such as being baptized in the Jordan and preaching on the Mount of Olives. His baptism in the Jordan, conducted by John the Baptist, serves as a significant moment symbolizing a new spiritual beginning, akin to Joshua’s crossing of the Jordan into the Promised Land. Additionally, Jesus’ preaching on the Mount of Olives, a location associated with messianic prophecy (Zechariah 14), reinforces his role as the expected messiah and reflects the symbolic actions of previous claimants like Theudas and the Egyptian. These deliberate parallels in the New Testament narrative emphasize continuity with Jewish messianic expectations and apocalyptic hopes.

In addition to these well-documented figures, several other leaders emerged shortly before and during the Jewish-Roman War, further fueling messianic hopes:

- Judas of Galilee (c. 4 BCE – 6 CE)

Judas of Galilee (also known as Judas the Gaulonite) was a key figure in the resistance to Roman taxation during the census under Quirinius in 6 CE. He led a significant uprising and founded the Zealot movement, which sought to overthrow Roman rule. While not explicitly declared a messiah, his actions fit the mold of a messianic liberator in the eyes of many Jews. - Simon of Peraea (c. 4 BCE)

A former slave of Herod the Great, Simon led a revolt against the Romans shortly after Herod’s death. He declared himself king, which many interpret as a messianic claim. His rebellion was quickly crushed by the Romans, and he was killed. - Athronges (c. 4 BCE)

Athronges was a shepherd who, along with his brothers, led a revolt against Roman rule, also after the death of Herod the Great. He declared himself king and led a significant following, though he was ultimately defeated. - Menahem ben Judah (66–70 CE)

During the Jewish-Roman War, Menahem, the son of Judas of Galilee, led a group of zealots and took control of parts of Jerusalem. He was considered a potential messianic figure but was eventually killed by rival factions. - Simon bar Giora (66–70 CE)

Simon bar Giora was a leader during the Jewish revolt against Rome. Some sources suggest he was seen as a messianic figure by his followers. After the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE, he was captured and executed by the Romans. - John of Gischala (66–70 CE)

Another prominent leader during the Jewish revolt, John of Gischala was viewed by some as a messianic contender. Like Simon bar Giora, he played a major role in the defense of Jerusalem before being captured by the Romans.

While not all these individuals explicitly declared themselves the messiah, they were often perceived as such by their followers. In the context of 1st-century Judaism, messianic expectations were closely linked to the hope for a divinely appointed leader who would liberate Israel from foreign oppression. Hence, any charismatic leader promising divine intervention or political liberation could be viewed as a potential messiah.

Destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, Francesco Haye, oil on canvas, 1867. The painting depicts the destruction of the Second Temple by Roman soldiers. The destruction of the temple in 70 CE was a pivotal event in Jewish history, marking the end of the Second Temple period and the beginning of the Jewish diaspora. The painting captures the chaos and devastation of the siege, with Roman soldiers looting the temple and setting it ablaze. The destruction of the temple had profound religious and cultural implications for the Jewish people, leading to the development of new religious movements and the transformation of Jewish worship practices. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

These repeated failures of messianic movements likely intensified apocalyptic expectations, ultimately setting the stage for the emergence of Christianity, which reinterpreted the messianic role in a spiritual rather than political context.

The prophecies in Daniel 9 and Isaiah 53

Many of these messianic figures met tragic ends, often at the hands of Roman authorities. Despite widespread expectations that the messiah would be a victorious warrior-king, specific biblical prophecies suggested a different narrative — one where the messiah would suffer and die.

Daniel 9 outlines a vision in which “seventy weeks” are decreed for the fulfillment of several key events, including the end of sin, the establishment of everlasting righteousness, and the anointing of a holy figure. Verse 26 explicitly states:

“After the sixty-two ‘sevens,’ the Anointed One will be put to death and will have nothing. The people of the ruler who will come will destroy the city and the sanctuary. The end will come like a flood: War will continue until the end, and desolations have been decreed.”

This passage was interpreted by many as a prophecy foretelling the death of the messiah and the subsequent destruction of Jerusalem, which Christians later linked to the crucifixion of Jesus and the Roman destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE.

Similarly, Isaiah 53 presents a poignant image of a suffering servant who bears the sins of others. The text reads:

“He was despised and rejected by mankind, a man of suffering, and familiar with pain. Like one from whom people hide their faces he was despised, and we held him in low esteem. Surely he took up our pain and bore our suffering, yet we considered him punished by God, stricken by him, and afflicted. But he was pierced for our transgressions, he was crushed for our iniquities; the punishment that brought us peace was on him, and by his wounds we are healed.”

Furthermore, the a Dead Sea peshar explicitly identifies the servant in Isaiah 53 with the messiah of Daniel 9. Dead Sea pesharim, found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, were written by a Jewish sect, likely the Essenes, and provide eschatological interpretations linking various biblical prophecies to their contemporary context. Carrier refers to such a pesher that strengthens the connection between the suffering servant motif and the messianic figure expected to usher in the end times. This linkage strengthened the interpretation that the messiah’s suffering and eventual death were divinely ordained events, paving the way for Christian theology to develop around the idea of Jesus as the prophesied suffering servant.

Psalm 89 also echoes this theme, lamenting the fate of God’s anointed:

“But you have rejected, you have spurned, you have been very angry with your anointed one. You have renounced the covenant with your servant and have defiled his crown in the dust.”

Together, these texts shaped the early Christian understanding of Jesus as the suffering messiah whose death was necessary for the salvation of humanity.

Why is connecting Isaiah 53 to Daniel 9 so important?

Throughout the Hebrew Bible, Israel’s suffering is often attributed to its collective sins. God’s delayed promises of deliverance were seen as contingent upon Israel’s repentance. Thus, the idea of a messiah who would die to atone for these sins was profoundly appealing.

The Gospel narrative appears to be a carefully constructed apocalyptic framework based on these scriptures. The connection between Isaiah 53 and Daniel 9 provided a roadmap for early Christian theology: A messiah who would die for the sins of the people, triggering the end times. It provided a framework for understanding the messiah as a figure whose suffering and death were integral to God’s plan of redemption.

The doomsday timetable in Daniel 9

The prophecy in Daniel 9 outlines a period of seventy weeks, interpreted as seventy sets of seven years. Various groups, including the authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls, experimented with different calendars to pinpoint the timeline. By one method, the prophecy appeared to predict that the messiah would be killed around 30 CE. According to this interpretation, the sequence of events would unfold as follows: the messiah would appear around 30 CE and be killed despite his innocence, after which Jerusalem would be destroyed by an evil prince. A few years later, God’s wrath would be poured out, culminating in the resurrection and the establishment of an eternal, blissful kingdom. However, this apocalyptic sequence did not materialize, prompting further reinterpretations and recalculations by various groups.

Left: Resurrection of the dead (Vision of the Valley of Dry Bones), fresco from the Dura-Europos synagogue. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: The Vision of The Valley of The Dry Bones, Gustave Doré, engraving, 1866. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – The Vision of the Valley of Dry Bones is a prophecy in chapter 37 of the Book of Ezekiel. In his vision, the prophet sees himself standing in the valley full of dry human bones. He is commanded to carry a prophecy. Before him, the bones connect into human figures; then the bones become covered with tendon tissues, flesh and skin. Then God reveals the bones to the prophet as the people of Israel in exile and commands the prophet to carry another prophecy in order to revitalize these human figures, to resurrect them and to bring them to the Land of Israel.

The book of Daniel itself was likely composed around 165 BCE during the Hasmonean resistance to Greek rule. However, it was presented as though it had been written centuries earlier, around 500 BCE, to lend it the appearance of ancient prophetic authority. The original purpose of Daniel’s timetable was to predict the end of the world in 164 BCE, coinciding with the expected defeat of the Seleucid Empire. When this prediction failed, later Jewish interpreters attempted to adjust the timeline, leading to various recalculations, one of which pointed to the 30s CE as the era when the messiah would appear.

Daniel’s prophecy itself can be seen as an attempt to reinterpret another failed prediction — Jeremiah’s prophecy of a seventy-year exile (Jeremiah 25:8). In Jeremiah, it was foretold that Babylon’s reign would end after seventy years, leading to God’s judgment on all nations. When this did not come to pass, the book of Daniel reinterpreted the seventy years as seventy weeks of years, extending the timeline significantly. Despite these reinterpretations, none of the revised prophecies came true, which in turn fueled messianic fervor and apocalyptic expectations in the 1st century CE.

Christianity

As we are used to from Carrier, he critically concludes that amid the plethora of messianic movements, one sect managed to survive: The followers of Jesus of Nazareth, who became known as Christians. Unlike other messianic groups that perished or were violently suppressed, early Christians adapted by reinterpreting the failed apocalyptic prophecies. They maintained that the end was still imminent but adjusted their theology to emphasize spiritual preparation and moral conduct over immediate eschatological fulfillment – however, the expectation of the apocalypse remained a central tenet of their faith.

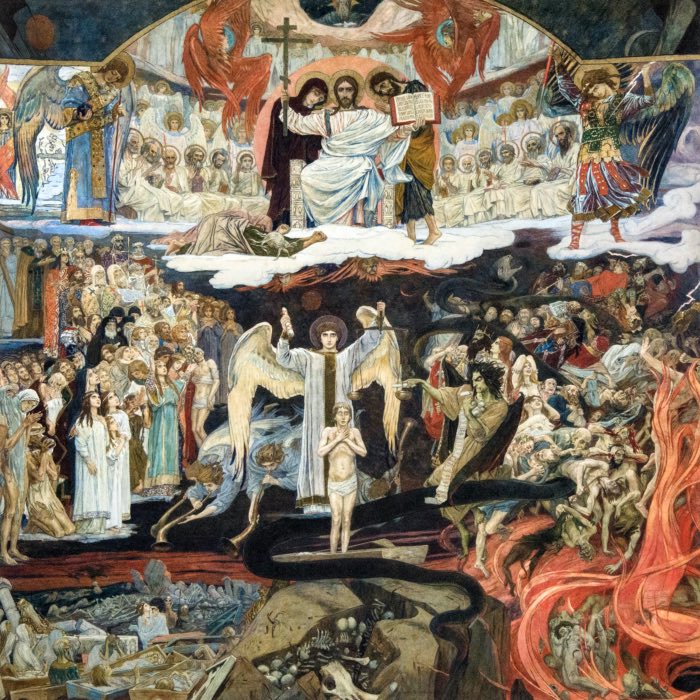

The Last Judgment, Viktor Vasnetsov, 1904. Christian will develop their own, complex eschatological beliefs, including the Last Judgment, the resurrection of the dead, and the establishment of God’s kingdom on earth – built upon the foundation of Jewish apocalyptic expectations. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

A crucial figure in this adaptation was Paul, who significantly broadened the appeal of Christianity by extending its promises beyond the Jewish community. Paul taught that non-Jews could also become part of God’s chosen people through faith in Jesus, effectively transforming Christianity into a universal movement. This shift in focus from a narrowly Jewish apocalyptic expectation to a more inclusive moral and spiritual community enabled Christianity to survive and grow, even as repeated doomsday predictions failed to materialize. Over time, the emphasis on ethical living and the promise of a future resurrection helped sustain the faith despite the persistent absence of the anticipated apocalypse.

Conclusion

Carrier concludes his talk in a cynical but very catchy summary: A failed prophecy from 600 BCE led to the forging of another prophecy in 165 BCE, which in turn inspired messianic expectations in the 1st century CE. These expectations culminated in a series of failed messianic movements, one of which evolved into Christianity, which has now been awaiting the apocalypse for over two millennia. In sum, we have 2500 years of unmet apocalyptic predictions.

The evolution of Jewish apocalyptic beliefs reflects a response to centuries of foreign domination and societal upheaval. Initially influenced by Persian Zoroastrian eschatology during the Babylonian exile, Jewish thinkers began to incorporate notions of a cosmic struggle between good and evil, divine judgment, and resurrection. The prophetic failures of Jeremiah and later the book of Daniel led to continual reinterpretations and recalculations of the end times.

By the 1st century CE, these expectations had reached a fever pitch, resulting in numerous messianic claimants. The turmoil of Roman occupation and the destruction of the Second Temple further intensified apocalyptic hopes. Amid this environment, early Christianity emerged as one of the few surviving movements, reconfiguring Jewish eschatology into a framework centered around Jesus as the suffering messiah.

Christianity’s endurance can be attributed to its shift from an immediate focus on apocalyptic fulfillment to an emphasis on spiritual and ethical living. Key figures like Paul expanded the movement’s reach by making it accessible to non-Jews, fostering its growth into a major world religion. Despite the persistent failure of apocalyptic predictions, Christianity adapted by emphasizing the promise of future salvation and moral community, ensuring its longevity over millennia.

What fascinated me about Carrier’s talkꜛ is how it reveals that entrenched beliefs, often perceived as absolute truths, are subject to change and reinterpretation over time. Far from being static, apocalyptic expectations evolved in response to historical circumstances, illustrating that religious ideologies are shaped by their social and political contexts rather than emerging in a vacuum. I think, many of such attempts can be seen as responses to the uncertainties faced during their times. It demonstrates that even deeply held convictions are products of historical processes and are continually reshaped by external pressures and internal reinterpretations.

References and further reading

- Richar Carrier, From Noah’s flood to rapture day: Dr. Richard Carrier uncovers the origins of doomsday beliefs, 12.11.2024, Talk recorded on YouTubeꜛ

- Richard Carrier, On the historicity of Jesus – Why we might have reason for doubt, 2014, Sheffield Phoenix Press, ISBN: 9781909697492

- Richard C. Carrier, Proving History: Bayes’s Theorem and the Quest for the Historical Jesus, 2012, Prometheus Books, ISBN: 978-1616145590

- Doherty, Earl, Lenz, Arnher E. (translator), The Jesus Puzzle: Did Christianity Begin with a Mythical Christ?, 2003, Angelika Lenz Verlag, ISBN: 978-3933037268

- Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, 2013, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780062206442

- Price, Robert M., The Christ-Myth Theory and Its Problems American Atheist Press, 2012, ISBN: 978-1578840175

comments