Richard Carrier and the historicity of Jesus: Was Christianity born from a mystery cult?

The question of whether Jesus of Nazareth was a historical individual or a purely mythical figure has long engaged theologians, historians, and laypeople alike. In his book, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (2014), Richard Carrier challenges conventional scholarly assumptions and proposes that Christianity could have originated without a historical founder. Instead, it might represent a Jewish adaptation of what Carrier calls a “mystery cult”, following patterns already established in other ancient Mediterranean religious traditions.

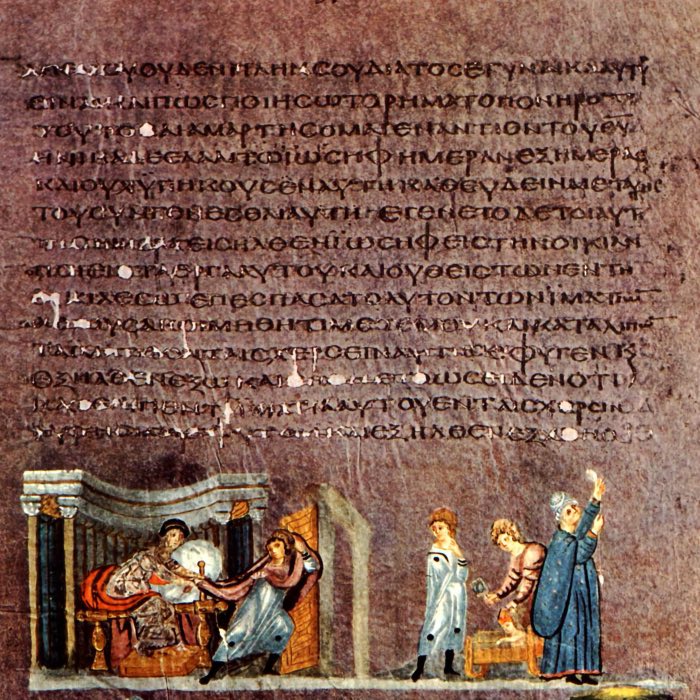

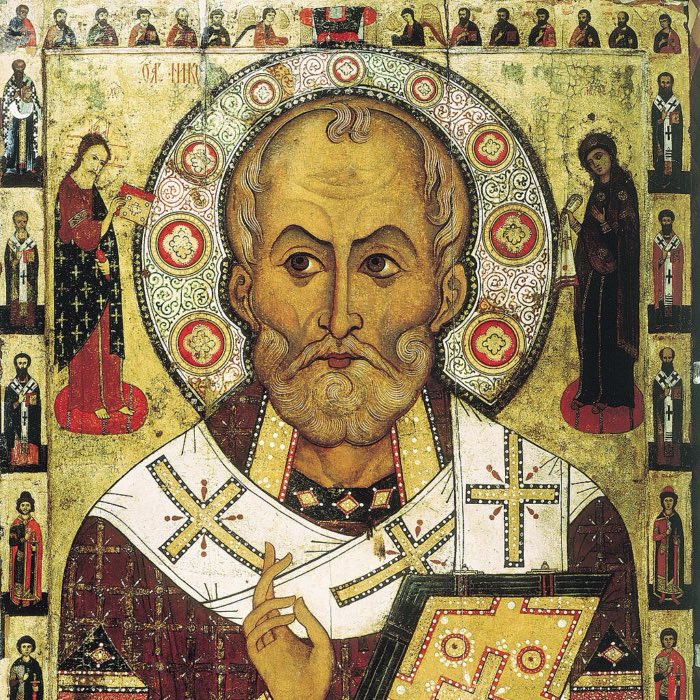

Deciphering the figure of Jesus as a mythological construct, interpreted by DALL•E.

Drawing upon the scholarly consensus, methodological critiques, parallel religious traditions, textual analysis of the Pauline epistles, and the literary nature of the Gospels, Carrier puts forth an argument suggesting that early Christians may have begun with the worship of a celestial Jesus and only later placed him into human history. This post summarizes and expands upon the main lines of argument Carrier presents, based on a recorded talk in which he outlines the major findings of his research.

Carrier’s core thesis: A mythical Jesus

Richard Carrier’s central thesis is that Jesus of Nazareth did not begin as a historical figure but was instead conceived as a celestial being. Carrier argues that early Christians initially believed in a pre-existent archangelic Jesus, who revealed divine secrets through visions and interpretations of Jewish scripture. Only later, Carrier suggests, was this celestial figure historicized into a human biography to strengthen doctrinal control and create a tangible origin for Christian teachings. In the following sections, we discuss the main arguments Carrier employs to support this thesis.

Carrier’s main arguments

Carrier’s thesis is supported by a range of arguments drawn from textual analysis, historical context, and comparative religious studies. In the following, we outline some of the key points Carrier presents in his case for a mythical Jesus.

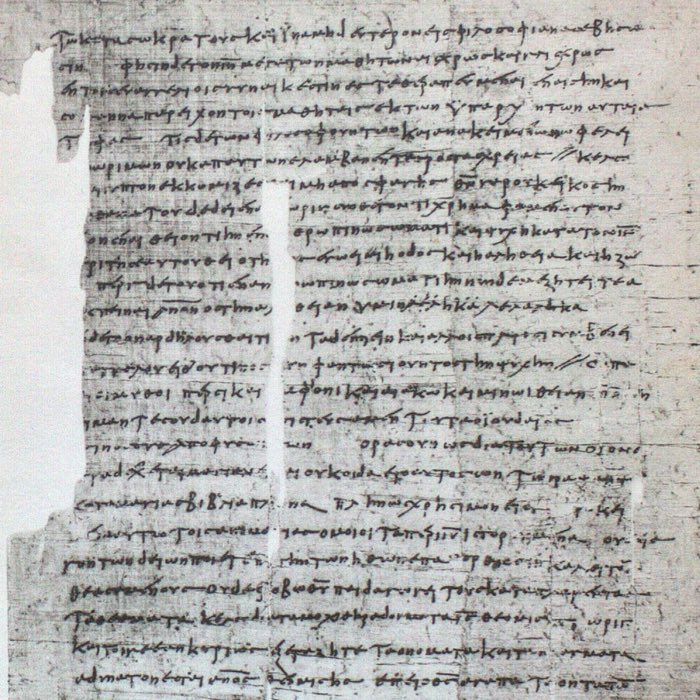

The Pauline epistles

The epistles of Paul, written in the 50s CE, form the earliest extant Christian texts. Carrier argues that these letters present Jesus not as a historical person but as a mythical or celestial figure, existing in a heavenly realm. According to Carrier, Paul’s writings depict a Jesus who was never described as a living teacher or prophet walking the earth, but rather as a preexistent being whose death and resurrection took place in a celestial sphere.

Traces of a non-earthly Jesus

Carrier argues that the earliest Christian documents, particularly the seven undisputed Pauline letters (e.g., Romans, Galatians, 1 Corinthians), present Jesus not as a historical person but as a mythical or celestial figure, existing in a heavenly realm. This general argument serves as a foundation for the more detailed analysis that follows, where Carrier explores specific passages and themes in Paul’s letters, such as the absence of references to an earthly ministry, ambiguous language about Jesus’s birth, and the interpretation of terms like “brothers of the Lord.” According to Carrier, Paul’s writings depict a Jesus who was never described as a living teacher or prophet walking the earth, but rather as a preexistent being whose death and resurrection took place in a celestial sphere.

This assumption — that Jesus was initially a celestial being rather than a historical person — is rooted in Carrier’s analysis of the Pauline epistles, which comprise the earliest extant Christian texts, written in the 50s CE — about two decades before the Gospels. Carrier argues that when examined without presuppositions, these letters only show a Jesus who communicates from heaven through visions and revelations and through hidden meanings in the Jewish scripture. Paul never clearly alludes to Jesus preaching in Galilee, calling or training disciples, or teaching in parables. Instead, Paul underscores revelation — repeatedly stating that his Gospel was not conveyed by any human being but through direct communication from the risen Christ (Galatians 1:11-12). According to Carrier, this observation fits better if we presume Paul understood Jesus as a cosmic figure only later historicized. Furthermore, Paul’s writings lack specific references to key aspects of Jesus’s earthly life, such as his birth, family, or ministry, details that would likely appear if Jesus were a recently known historical figure.

Carrier also draws upon Jewish angelology, a tradition in which celestial beings, particularly archangels, were assigned critical roles in divine plans. He suggests that this perspective helps explain Pauline references to Jesus being ‘born of a woman’ in a non-literal sense, implying a divinely fashioned rather than naturally born body. By linking Jesus to the role of an archangel, Carrier argues that early Christians understood him as a cosmic savior whose flesh was created directly by divine intervention — an interpretation that aligns with Jewish angelological traditions and supports the broader mythicist thesis.

“Born” or “made”?

Some of the most cited Pauline passages appear to indicate an earthly Jesus. Two key arguments include references to Jesus being “descended from David” and “born of a woman.” Yet Carrier points to the original Greek terms, which suggest “manufactured” or “made”, not the usual word denoting human birth. This ambiguity opens an interpretative possibility that Paul perceived Jesus’s flesh as divinely formed — similar to how Adam’s body was shaped from the dust.

Carrier contends that, in certain manuscript traditions, scribes even corrected or replaced terms in ways that push for a more conventional notion of human birth, implying that earlier Christians may not have originally taken the text in a strictly literal sense.

Brothers of the Lord

A further objection to the mythicist perspective is that Paul mentions “brothers of the Lord”. Traditionally, scholars assume these “brothers” were Jesus’s literal siblings, making him a historical person. However, in many early Christian contexts, “brothers” (and “sisters”) was a generic term for fellow believers. Carrier reads Paul in light of Galatians 3:26–29, where all baptized Christians become adopted sons (and hence siblings) of Christ. The ambiguous nature of the phrase “brothers of the Lord” does not definitively point to a real flesh-and-blood family, but could rather be an internal reference to baptized followers.

Jesus as a sacrifice in heaven

In Hebrews 9:11-12 (if the letter to the Hebrews is attributed to Paul), it is described that Jesus did not enter an earthly sanctuary, but a “heavenly sanctuary” in order to offer a sacrifice there. Carrier interprets this to mean that Paul and his followers believed that the salvation event took place in a heavenly sphere, not on earth.

“Angel Jesus”

Jesus as a celestial figure in Paul’s letters

Carrier derives the idea of Jesus as an angel primarily from Paul’s letters, though Paul never explicitly refers to Jesus as an “angel.” Instead, Carrier argues that certain descriptions of Jesus’s nature and role exhibit characteristics typical of heavenly angels in Jewish thought. He speculates that Paul viewed Jesus as an already existing celestial figure who later took on human form.

The name “Jesus” as a functional title

One key argument Carrier presents is that the name “Jesus” (Yeshua, meaning “God saves”) was initially a functional title rather than a personal name. This interpretation aligns with other angelic names in Jewish tradition, such as Michael (“Who is like God?”) and Gabriel (“God is strong”), which reflect their divine missions. Carrier suggests that early Christians conceived of Jesus as a heavenly being whose primary role was to bring salvation.

Jesus as mediator and preexistent being

Paul consistently describes Jesus as a mediator between YHWH and humanity, a role traditionally assigned to angels in Jewish theology. In Galatians 3:19, Paul mentions that the Law was delivered through angels, implying that divine revelations often came through such intermediaries. Carrier argues that this framework supports the idea that Jesus, too, was initially understood as an angelic figure who facilitated a new covenant.

Additionally, Carrier emphasizes the theme of preexistence and self-humiliation in Philippians 2:6-8, where Paul writes that Jesus existed “in the form of God” before “taking the form of a servant” and becoming human. Carrier interprets this passage as evidence that Jesus was originally perceived as a heavenly being who descended into the material world, echoing other Jewish angelic traditions where celestial beings take on earthly roles.

Jesus as the ‘firstborn among brothers’

Another point Carrier highlights is Paul’s description of Jesus as the “firstborn among many brothers” in Romans 8:29. Carrier speculates that these “brothers” could be understood as other angels, making Jesus the preeminent figure among a heavenly host. This interpretation further supports the notion that Jesus was regarded as an exalted angelic being within an established celestial hierarchy.

Implicit angelology and Familiarity with the concept

Despite the lack of an explicit designation of Jesus as an angel, Carrier argues that Paul’s audience would have already been familiar with the concept of angelic mediators and would have understood Jesus within this framework without requiring further clarification.

Parallels with the Wisdom tradition

Carrier also draws a parallel between Jesus and the personified Wisdom of God (Chokhmah) in Jewish literature, which is depicted as a preexistent entity involved in creation (Proverbs 8:22-31). Paul’s portrayal of Jesus as a preexistent being who participates in creation (1 Corinthians 8:6, Colossians 1:16) reflects this Wisdom tradition, suggesting that Jesus was initially conceived as a personification of divine attributes, later evolving into a distinct heavenly figure with salvific functions.

Parallels in ancient mystery cults

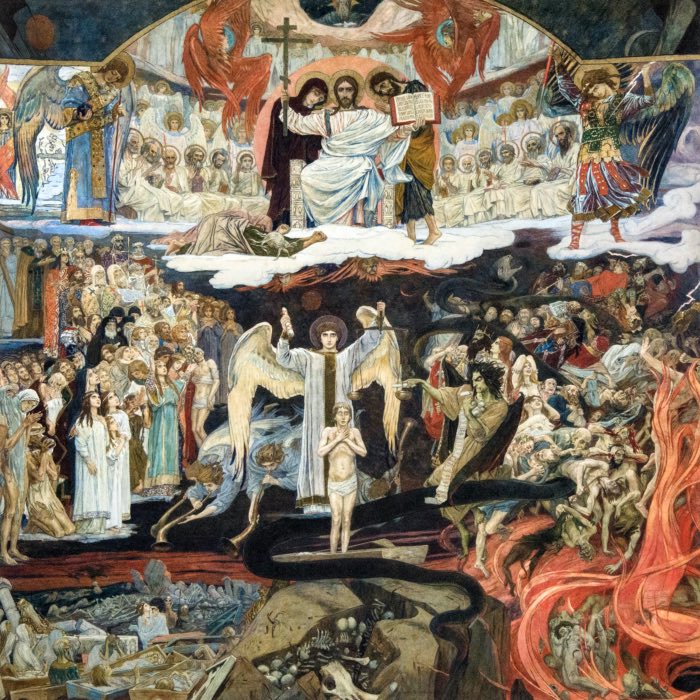

Carrier traces a long-standing pattern in which mythic or semi-mythic figures were retroactively given historical biographies. He points to Old Testament patriarchs such as Abraham and Moses, who, despite being associated with genealogical details and historically resonant contexts, are often surrounded by legendary narratives and miraculous events that many modern scholars regard as predominantly non-historical.

In the broader pagan world, mystery cults of the Hellenistic and Roman periods featured savior deities such as:

- Osiris: Egyptian deity associated with death, resurrection, and the afterlife. Followers believed in personal salvation through symbolic participation in Osiris’s death and rebirth, often involving ritual reenactments of Osiris’s myth. Carrier suggests that early Christian baptism rites might have drawn on similar practices, symbolizing the believer’s identification with Jesus’s death and resurrection, akin to the way followers of Osiris symbolically partook in their deity’s journey through death to new life.

- Dionysus: Greek god of wine, fertility, and ecstasy. Dionysian rites involved initiations and symbolic rebirth, emphasizing mystical union with the deity. These rites often included intoxicating substances, music, and ecstatic dances designed to induce altered states of consciousness, allowing initiates to experience a direct connection with Dionysus. Early Christian communal rituals, which symbolized unity with Christ, show parallels in their emphasis on communal participation and symbolic acts representing spiritual transformation.

- Mithras: Persian-origin deity popular in the Roman Empire. Mithraic cults featured elaborate initiations and the promise of immortality through Mithras’s cosmic sacrifice. Mithraic rituals included a complex series of seven initiatory grades, each associated with specific symbolic meanings. The Mithraic banquet ritual, involving a shared sacred meal symbolizing divine communion, has notable parallels with the early Christian Eucharist.

- Zalmoxis: Thracian deity who was believed to offer immortality to his followers. The cult of Zalmoxis involved initiatory rites and teachings about life after death. Followers of Zalmoxis practiced a form of esoteric wisdom, emphasizing personal transformation and preparation for the afterlife. Early Christian eschatological teachings about resurrection and eternal life bear similarities to Zalmoxian beliefs, particularly in their focus on immortality and spiritual renewal.

- Romulus: Legendary founder of Rome, later deified. Romulus’s apotheosis symbolized the divine approval of Roman rule and offered a model of heroic ascent to godhood. The story of Romulus, including his mysterious disappearance and later deification, mirrors elements of the Christian resurrection narrative, where Jesus’s earthly departure culminates in his exaltation as a divine figure. Both narratives serve to legitimize the authority of their respective religious communities.

- Inanna: Mesopotamian goddess of love, war, and fertility. Inanna’s descent into the underworld is one of the earliest known myths involving death and resurrection. She undergoes a symbolic death, is stripped of her powers, and is later revived and restored to her former glory. This myth shares thematic similarities with the Christian narrative of Jesus’s death and resurrection, highlighting the concept of triumph over death and renewal of life. Early Christian theology may have drawn upon such motifs in constructing its soteriological framework.

These figures (except for Mithras) were revered as “dying-and-rising gods”, offering personal salvation through symbolic death and rebirth. Although these deities were sometimes linked to specific historical times and places, historians generally agree that they were never intended to represent actual historical individuals.

Carrier highlights a widespread religious development during the late Hellenistic and early Imperial periods, where local cults often blended with Greek-style mystery religions, resulting in syncretic faiths centered on personal salvation and initiation rites. He argues that, given this cultural backdrop, it was almost inevitable that a “Jewish version” of such a mystery religion would emerge, blending Jewish theological concepts with Hellenistic soteriological themes.

In Carrier’s view, Christianity was not an unprecedented religious innovation but rather a Jewish adaptation of this mystery-cult model. Key elements such as a saving deity, a passion narrative, the promise of triumph over death, and the goal of ultimate union with the divine were all prevalent within the religious environment of the early Roman Empire. Christianity, therefore, fit seamlessly into this existing trend of syncretic salvation cults, while adapting these themes to a distinctly Jewish context.

Literary nature of the Gospels

Late composition and allegorical structure

The canonical Gospels — Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John — appear between the late 60s CE and the early 2nd century, placing them decades after Paul’s letters. Carrier draws from a range of scholarship characterizing these texts as highly literary works, constructed primarily to convey theological and allegorical points rather than to serve as historiographies. Mark’s Gospel, in particular, resembles an “extended parable”, wherein every scene can be read symbolically or thematically.

Exemplifying the fig tree narrative

A notable illustration Carrier highlights is Mark’s story of Jesus cursing a fig tree for failing to produce fruit out of season. This episode would seem illogical if interpreted literally, yet scholars have proposed that the fig tree signifies the Jewish Temple, with Jesus’s “cursing” symbolizing its destruction in 70 CE. This would indicate that Mark’s audience was dealing with post-70 theological questions, shaping the story retroactively.

Carrier points to numerous comparable examples throughout the Gospels — apparent “sandwiched” episodes, inclusio structures, and supernatural events — difficult to reconcile with historical reportage. Such features suggest that the evangelists composed narratives designed to illustrate theological truths, not to document raw history.

Contradicting epistolary silence

Remarkably, the epistles never mention Jesus’s parables, exorcisms, or controversies with Pharisees — central elements of the synoptic Gospels. Carrier sees these late and elaborately symbolic Gospel compositions as further evidence that early Christians first conceptualized Jesus as a celestial being, only to situate him in human history when allegorical storytelling better served community formation and doctrinal unity.

Additional evidence and analogies

Non-independent sources and forgeries

Besides the four canonical Gospels, many later Christian documents (such as infancy Gospels) are demonstrably fabricated or heavily embellished. Carrier notes that the famous passages in Josephus that mention Jesus are likely medieval interpolations, or at best derivative of Christian claims.

If Josephus were indeed repeating church tradition in the late 1st century, that tradition would already be shaped by whatever stories existed about Jesus at the time. Thus, Josephus would not be an independent witness, even if those references were authentic. Carrier further disputes other supposed non-Christian corroborations (e.g., Thallus) as misread or nonexistent.

The ‘Roswell’ parallel

Carrier provides an analogy to explain how a purely celestial Jesus could have been historicized. He compares the development of the Jesus story to the post–World War II Roswell incident in the United States. Within just a few decades, rumors of alien bodies and flying saucers had proliferated, despite the original story likely involving mere sticks and tinfoil. Analogously, 1st-century believers in a revelatory Jesus need not have had any historical figure to start with. Only later might they have projected such stories into a historical frame, leaving us with a “pious fraud” turned widely accepted tradition.

Carrier’s conclusion: The euhemerization of Jesus

Bases on his arguments we have discussed above, Carrier suggests that Jesus was initially conceived as a celestial being — a pre-existent archangel — who revealed divine secrets through visions and hidden meanings in Jewish scripture. What eventually became the “Gospel”, according to Carrier, emerged not from the testimony of earthly disciples, but from these revelations. Early Christian communities, he argues, believed that this archangelic Jesus had outwitted Satan by incarnating and being crucified in a spiritual realm, somewhere in the heavens. This heavenly crucifixion, Carrier contends, was meant to atone for humanity’s sins and herald the eschatological age. In this framework, no historical Galilean context was initially assumed; it was only later that Christian authors situated this celestial figure within a human narrative to ground the story in history.

To support his thesis, Carrier draws parallels between Jesus and other ancient Mediterranean “dying-and-rising gods” such as Osiris, Dionysus, and Inanna. These deities often symbolized themes of death and rebirth, framed within mythic rather than historical contexts. Carrier speculates that Jesus similarly originated as a purely celestial savior figure, worshipped by an apocalyptic Jewish sect blending Jewish eschatological beliefs with Hellenistic mystery cult traditions. Over time, Jesus was historicized, making his story more relatable and providing a firmer foundation for the growing Christian movement.

Carrier uses the term “euhemerization”, referencing the ancient Greek writer Euhemerus, who portrayed gods as historical figures by recasting them as legendary rulers or kings of a distant past. In Carrier’s view, early Christians engaged in a similar process: they began with a heavenly Jesus and recast him as a historical figure to establish doctrinal authority. Anchoring Jesus in history allowed early Christian leaders to marginalize rival sects that based their claims on new revelations. By asserting an unbroken lineage from disciples who had supposedly known a real, historical Jesus, dominant Christian groups could legitimize their doctrines and dismiss alternative interpretations. This “historicizing” of Jesus thus became a potent means of institutional control and theological dominance.

Paul’s motivation

Carrier speculates about the origins of the belief in a mythological Jesus and the possible motivations of Paul and other early Christians to write about a heavenly Messiah.

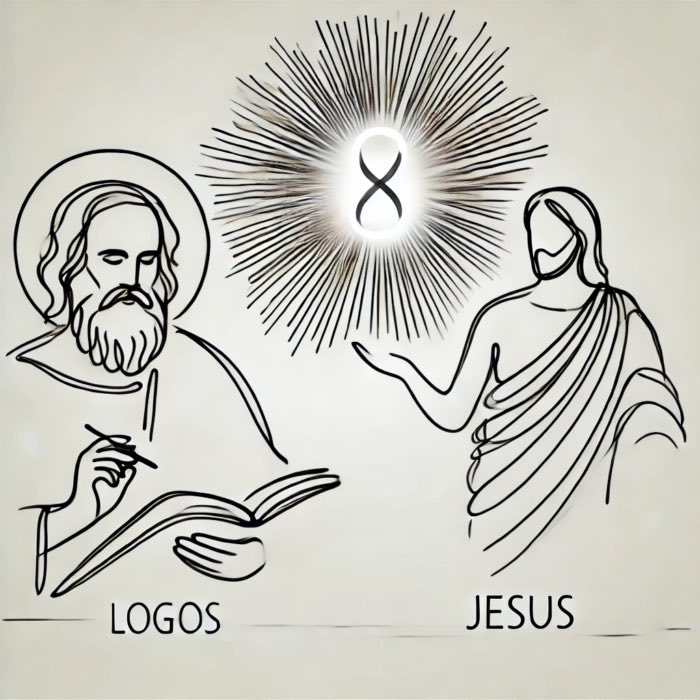

Jewish roots

Carrier argues that the idea of a heavenly Messiah was not novel and had precedence in certain Jewish circles, drawing on key influences from Jewish philosophy and apocalyptic literature. Philo of Alexandria, a Jewish philosopher, described a heavenly figure called the logos, who acted as an intermediary between YHWH and humanity. Philo depicted the Logos as a divine being that existed in a higher spiritual realm, mediating between the material world and the divine. In addition to Philo’s philosophical framework, Jewish apocalyptic literature, such as the Book of Daniel and [1 Enoch](/weekend_stories/told/2025/2025-01-11-enochs_influence_on_jesus_narrative/, features heavenly beings tasked with cosmic roles in YHWH’s salvific plan, often operating in spiritual rather than earthly realms.

Inspired by these existing traditions, Carrier suggests that early Christians developed the belief in a heavenly redeemer, a divine figure who underwent crucifixion in a spiritual realm to atone for humanity’s sins. Unlike later interpretations, this Messiah did not initially appear on Earth but completed his salvific mission entirely in a celestial domain.

Paul’s central role

Carrier identifies Paul as a key figure in spreading the belief in a heavenly Jesus. He suggests that Paul’s theological framework was shaped by visions and ecstatic experiences that convinced him of the existence and redemptive role of a celestial Messiah.

Paul’s motivations, according to Carrier, could have been driven by several factors:

- Missionary zeal: Paul viewed himself as divinely appointed to bring the message of salvation to the Gentiles. The belief in a heavenly Messiah who had already conquered death provided a universal and compelling message that could appeal to both Jews and Gentiles.

- Apocalyptic expectation: Like many of his contemporaries, Paul expected the imminent end of the world and the return of the Messiah. A cosmic savior who would soon appear in glory fit well within this apocalyptic worldview.

- Rejection of traditional Messianic expectations: Paul may have rejected the conventional Jewish idea of a political, earthly Messiah, as it appeared to have failed in liberating the Jewish people from Roman rule. Instead, he promoted a spiritual Messiah who offered personal and cosmic redemption.

Early Christian communities

Carrier argues that the belief in a mythological Jesus spread among early Christian communities primarily through two key processes: visions and scriptural exegesis. Paul frequently emphasizes that his Gospel was received not from human sources but through direct revelation from Christ, as highlighted in Galatians 1:11-12. Carrier interprets this as evidence that the early Christians did not initially conceive of Jesus as a historical figure, but rather experienced him through visionary encounters. These revelations, according to Carrier, formed the basis of early Christian faith, with believers interpreting their spiritual experiences as direct communication with a celestial savior.

In addition to visions, early Christians engaged in extensive reinterpretation of Jewish scripture. Paul and other early believers sought to uncover hidden meanings in the Hebrew Bible that, when viewed allegorically, seemed to predict the suffering, death, and resurrection of a messianic figure. Carrier suggests that the phrase “according to the Scriptures” in 1 Corinthians 15:3 reflects this allegorical approach, implying that the narrative of Jesus’s death and resurrection was derived from symbolic readings of ancient texts rather than from historical events. Thus, visionary experiences combined with scriptural reinterpretation provided the theological framework for a mythological Jesus long before he was cast as a historical figure.

Transition to historicization

Carrier suggests that the belief in a mythological Jesus was gradually historicized over time for several reasons:

- Consolidation of faith: Presenting Jesus as a historical figure made the faith more relatable and credible to new converts.

- Competition with other groups: A historical Jesus allowed dominant Christian sects to claim authority through apostolic succession, marginalizing rival sects that relied on ongoing revelations.

- Theological narrative: The Gospels, according to Carrier, were theological constructs designed to ground the celestial Jesus in a historical context, creating a compelling narrative for the early Christian movement.

A synthesis of Jewish and Hellenistic elements

The development of early Christian belief, according to Carrier, involved the synthesis of Jewish apocalyptic expectations, mystical experiences, and the influence of surrounding Hellenistic religious traditions. Paul’s role was instrumental, as he not only shaped and disseminated the belief in a heavenly Jesus but also provided the theological groundwork through his letters and missionary efforts. This belief, initially based on revelations and scriptural reinterpretations, gradually evolved into a more concrete narrative as later Christian writers placed Jesus within a historical framework. Carrier’s analysis highlights how these processes led to the eventual historicization of a celestial figure, offering a speculative but compelling alternative to traditional views on Christian origins by underscoring the fusion of Jewish and Hellenistic elements in the formation of early Christian doctrine.

Implications of a non-historicity of Jesus

If we speculate that Carrier’s hypothesis is correct, it would necessitate a fundamental reinterpretation of Christianity’s origins. Rather than being a unique revelation centered on a historical figure, Christianity would need to be understood as a Jewish-Hellenistic mystery cult, akin to those of Mithras, Osiris, Dionysus, or Orpheus. In this scenario, early Christian rituals, theology, and narratives would be viewed as part of a broader cultural milieu of syncretic salvation cults prevalent in the Greco-Roman world.

Christianity as a Jewish mystery cult

Initiation through rituals

In this perspective, Christianity, like other mystery cults, would be based on secret teachings and ritual initiations. Baptism, for example, could be interpreted as an initiation rite symbolizing the believer’s participation in the death and resurrection of the celestial Jesus (Romans 6:3-4). This ritual would serve as a symbolic gateway into the mysteries of salvation.

Salvation through mystical union

The central salvific motif would not focus on moral conduct in earthly life but rather on achieving a mystical union with the heavenly Jesus. Just as followers of Osiris or Dionysus symbolically partook in the death and rebirth of their deities, early Christians would have viewed participation in Jesus’s death and resurrection as the path to immortality and spiritual fulfillment.

Secret revelations

Paul frequently speaks of revelations and “mysteries” (1 Corinthians 2:7, Romans 16:25) accessible only to the initiated. Carrier suggests that these references indicate a tradition of secret teachings, reminiscent of the esoteric knowledge imparted in mystery cults. In this context, Paul’s epistles would represent a form of early Christian mystagogy (initiation instruction), guiding initiates into deeper spiritual truths.

Jesus as a mythological savior deity

Parallels to dying and rising gods

If Jesus was originally conceived as a mythological savior deity, he would closely parallel figures such as Osiris, Mithras, or Dionysus, who offered immortality through their death and resurrection. In this view, Jesus’s crucifixion would not be a one-time historical event but an eternally significant cosmic act, performed in a mythical realm to secure universal salvation.

Heavenly salvation rather than Earthly liberation

The message of early Christianity, according to this interpretation, would have been primarily concerned with heavenly salvation rather than political or social liberation. This focus on spiritual deliverance could explain why early Christians distanced themselves from earthly power struggles and instead emphasized the imminent arrival of a heavenly kingdom.

Paul as the founder of the cult

If Carrier’s theory holds, Paul should be seen not as a disciple of a historical Jesus but as the founder of a new mystery cult, synthesizing Jewish apocalyptic expectations with Hellenistic notions of salvation. His theological innovations, centered on a heavenly Christ, would have provided the foundation for what became the Christian faith.

Gospels as mythical narratives

In this framework, the Gospels would not be historical accounts but rather theological myths, crafted to place the heavenly Jesus within a historical narrative. Like the stories of Heracles or Dionysus, the Gospel narratives could be understood as allegorical tales conveying profound spiritual truths through symbolic storytelling.

Christianity in competition with other mystery cults

Under this interpretation, early Christianity would have been one of many competing mystery cults in the Greco-Roman world. Several factors might have contributed to its eventual dominance:

- Monotheism: Unlike polytheistic mystery cults, Christianity offered a single, universal God, appealing to a broad audience.

- Ethical teachings: Christianity combined mystery cult elements with a strong ethical framework, distinguishing itself from other religious movements.

- Community support: Early Christian communities provided social cohesion and mutual aid, making them attractive in a time of widespread social instability.

- Historization of myth: By grounding the story of Jesus in a historical context, Christianity gained an additional layer of credibility and relatability that other cults lacked.

Futility of fundamentalist appeals

Undoubtedly, Christianity began as a fluid, evolving religious movement, adapting to diverse cultural influences and theological developments. Even viewed through Carrier’s mythicist lens, the faith’s origins remain complex and multifaceted. Attempts to return to any imagined “original” form of Christianity would be misguided, as the faith was never monolithic or static. Instead, early Christian communities engaged in a dynamic process of theological innovation and adaptation, responding to the needs and challenges of their time.

Revising the self-image of Christianity

The self-image of Christianity as an original Jewish sect must also be revised in light of Carrier’s hypothesis. According to this view, the beginnings of Christianity are better understood as part of a syncretistic process in which Jewish, Hellenistic, and Roman influences merged to create a new religious movement. Just as the cult of Osiris blended Egyptian and Greek elements, early Christianity can be seen as a similar fusion, incorporating distinctively Jewish traditions into a broader Greco-Roman mystery cult framework.

This reinterpretation suggests that Christianity was not a purely Jewish phenomenon but one of the numerous “fashionable” mystery cult movements that emerged in the Roman Empire. By presenting itself as a religion offering a singular path to eternal life and a universal savior figure, Christianity positioned itself as a unique yet familiar alternative within the competitive religious landscape of the time. Carrier’s argument implies that this syncretic blending allowed Christianity to stand out among other mystery cults, providing it with both a sense of ancient legitimacy through its Jewish roots and broader appeal through its incorporation of Hellenistic and Roman religious elements. This dual identity may have contributed significantly to the rapid spread of Christianity and its eventual dominance in the Roman world.

Church as custodian of a mystery cult

The Church would be seen as the head and administrator of a mystery cult, responsible for safeguarding and transmitting the secret teachings and rituals integral to salvation. In practice, the Church fulfilled this role already in its history. The clergy functioned as intermediaries between the divine and the faithful, guiding believers through the mysteries and interpreting their spiritual significance. The sacraments, such as baptism and the Eucharist, were already understood as initiatory rites leading believers toward a mystical union with the cult’s salvific deity, Jesus Christ. Thus, the Church’s role as the custodian of a mystery cult would be a continuation of its historical function.

Consequences for theology: Christianity as a spiritual path

If Christianity originated as a mystery cult, this reinterpretation would carry profound implications for its theology. First, the concept of Jesus as a historical role model would need to be discarded. The idea that Jesus served as a moral exemplar rooted in historical events would no longer hold, as his significance would instead derive from his symbolic and mythological role as a savior figure. This shift would fundamentally alter the basis of Christian ethical teaching, moving away from historical imitation toward symbolic participation in a divine narrative.

Additionally, there would be a diminished emphasis on historical facts. Debates surrounding the historicity of key events, such as the resurrection, would lose their relevance. Instead, theological focus would shift toward interpreting the spiritual and allegorical meanings embedded in these narratives. The resurrection, for example, would be seen not as a literal event but as a metaphor for personal transformation and the promise of eternal life.

Finally, Christianity could be reimagined as a spiritual path akin to ancient mystery cults. In this view, the faith would emphasize rituals, mystical experiences, and personal transformation over adherence to historical doctrines. Practices such as baptism and the Eucharist would be understood as initiatory rites leading believers toward a mystical union with the divine. This interpretation would place Christianity within a broader tradition of religious movements that seek to bridge the human and the divine through symbolic acts and spiritual enlightenment.

Critical perspectives on Carrier’s theory

Carrier’s hypothesis, though intriguing, has been met with significant criticism from both historians and theologians. Critics argue that Carrier’s reliance on parallels with ancient mystery cults and his interpretation of Paul’s writings as exclusively referring to a celestial Jesus are speculative and lack sufficient textual evidence.

Methodological concerns

One of the primary critiques involves Carrier’s application of Bayesian reasoning to historical inquiry. While Bayesian analysis is a powerful statistical tool, many historians contend that its use in evaluating ancient texts and events is problematic. Historical data is often incomplete and context-dependent, making it difficult to assign precise probabilities to complex historical questions. Critics argue that Carrier’s prior assumptions about the prevalence of mythical savior figures in antiquity skew his analysis toward a predetermined conclusion.

Overreliance on parallels

Carrier’s comparison of Jesus with figures from Hellenistic mystery cults, such as Osiris and Dionysus, has been criticized for overreliance on superficial similarities, also known as parallelomania. While dying-and-rising god motifs were present in some ancient religions, many scholars emphasize that Jewish monotheism was distinct from Greco-Roman polytheistic traditions. They argue that early Christian theology emerged primarily from a Jewish apocalyptic context, making the direct influence of mystery cults less plausible than Carrier suggests.

Selective reading of Paul’s letters

Another point of contention is Carrier’s interpretation of Paul’s epistles. Critics note that while Paul does emphasize revelation and visions, he also makes references to Jesus’s human lineage, such as being “descended from David” (Romans 1:3) and “born of a woman” (Galatians 4:4). These passages are traditionally understood as affirmations of Jesus’s historical existence. Carrier’s argument that these references are metaphorical or non-literal is viewed by some as an overly speculative reading that disregards conventional interpretations.

The role of early Christian communities

Scholars also question Carrier’s depiction of early Christian communities as primarily oriented around mystical experiences and esoteric teachings. While early Christianity did involve visionary elements, most historians argue that it also had a strong ethical and communal dimension grounded in the teachings of a historical Jesus. Carrier’s emphasis on Christianity as a mystery cult is seen by some as an oversimplification that underplays the diversity of early Christian beliefs and practices.

Conclusion of critical perspectives

Despite these criticisms, Carrier’s work has contributed to the ongoing debate about the historicity of Jesus by encouraging scholars to reexamine traditional assumptions and explore alternative explanations. His hypothesis serves as a provocative challenge to established narratives, prompting further investigation into the complex interplay of history, myth, and theology in the origins of Christianity.

Conclusion

Richard Carrier’s hypothesis presents a bold and speculative challenge to the traditional understanding of Christian origins. His core thesis posits that Jesus of Nazareth was not initially a historical figure but a celestial being, whose story was later historicized by early Christian communities. By drawing on Jewish angelology, Paul’s writings, and parallels with Hellenistic mystery cults, Carrier builds an argument that early Christianity began as a mystical faith centered on a heavenly savior. According to Carrier, Paul’s epistles depict a cosmic Jesus who revealed divine truths through visions and scriptural interpretations, without ever existing in a human context. This interpretation aligns with Jewish apocalyptic expectations and Hellenistic religious trends of the period.

Carrier emphasizes Paul’s critical role in the formation of early Christianity. He portrays Paul as a visionary theologian who shaped the belief in a heavenly Messiah through his missionary efforts. Paul’s emphasis on personal revelation and mystical experiences provided the theological groundwork for a cult-like movement, which later adapted Jewish scripture to fit its salvific narrative. Over time, as the movement grew, the figure of Jesus was historicized, allowing early Christian leaders to consolidate doctrinal authority and establish institutional control.

Carrier’s comparison of Christianity with other ancient mystery cults underscores his broader argument that the faith did not emerge in a vacuum but was part of a syncretic religious milieu. Mystery cults of the Greco-Roman world often revolved around dying-and-rising gods, personal salvation, and initiation rites. Carrier suggests that early Christianity followed a similar pattern, positioning Jesus as a divine figure whose death and resurrection promised eternal life. The Gospels, in this framework, are seen as theological narratives rather than historical accounts, crafted to place the celestial Jesus into a relatable human setting.

The implications of Carrier’s hypothesis are significant. If Christianity indeed began as a Jewish-Hellenistic mystery cult, its theology would require a fundamental reinterpretation. The emphasis would shift from historical events to symbolic and mystical meanings, reframing Jesus as a mythological savior rather than a historical moral exemplar. Such a shift would diminish the relevance of debates over historicity and focus instead on Christianity as a spiritual path emphasizing ritual, mysticism, and personal transformation.

While Carrier’s theory remains speculative and controversial, it offers a provocative lens through which to reconsider the origins of one of the world’s major religions. By highlighting the fusion of Jewish traditions with Hellenistic religious elements, Carrier invites scholars and readers alike to explore how myth, history, and theology intertwined in the development of early Christianity.

References and further reading

- Richard Carrier, On the historicity of Jesus – Why we might have reason for doubt, 2014, Sheffield Phoenix Press, ISBN: 9781909697492

- Richar Carrier, Jesus from outer space: What the earliest Christians really believed about Christ, 2020, Pitchstone Publishing, ISBN: 978-1634311946

- Richard C. Carrier, Proving History: Bayes’s Theorem and the Quest for the Historical Jesus, 2012, Prometheus Books, ISBN: 978-1616145590

- Doherty, Earl, Lenz, Arnher E. (translator), The Jesus Puzzle: Did Christianity Begin with a Mythical Christ?, 2003, Angelika Lenz Verlag, ISBN: 978-3933037268

- Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, 2013, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780062206442

- Price, Robert M., The Christ-Myth Theory and Its Problems American Atheist Press, 2012, ISBN: 978-1578840175

- Crossan, J. D., The Power of Parable: How Fiction by Jesus Became Fiction about Jesus, 2013, HarperOne, ISBN: 978-0061875700

- Helms, R., Gospel Fictions, 1988, Prometheus Books, ISBN: 978-0879755720

- Karlheinz Deschner, Der gefälschte Glaube - eine kritische Betrachtung kirchlicher Lehren und ihrer historischen Hintergründe, 2004, Knesebeck, ISBN: 9783896602282

comments