Scriptures rewritten: How pseudepigraphy shaped the New Testament

The New Testament, a foundational collection of texts for Christianity, consists of 27 books that span a range of literary genres, including historical narratives, theological treatises, letters, and apocalyptic visions. Traditional Christian views hold that these books were written by apostles or their close associates, lending them an air of direct apostolic authority. However, modern biblical scholarship has questioned the authenticity of several New Testament books, suggesting that many were forged or editorially reworked in antiquity. In this post, we explore the phenomenon of pseudepigraphy (writing in the name of another) in the New Testament, the historical context of forgery, and the implications for understanding early Christian communities.

“Scriptures rewritten: How pseudepigraphy shaped the New Testament”, interpreted by DALL•E.

The context of pseudepigraphy in antiquity

In antiquity, pseudepigraphy was a widespread literary practice. Unlike modern notions of forgery, which are associated with fraud and deception, ancient pseudepigraphy often served more complex purposes. It was common in Jewish, Greek, and Roman literary traditions to attribute works to revered figures, thereby enhancing the text’s authority and legitimacy. Philosophical schools frequently composed treatises in the name of their founders, while religious movements produced writings under the names of prophets or apostles to strengthen doctrinal positions.

In the context of early Christianity, pseudepigraphy played a similar role. As the nascent Christian movement sought to define its identity and beliefs, attributing writings to apostolic figures lent them the weight of direct divine inspiration and continuity with Jesus’ original disciples. This practice, while accepted or even expected in some circles, has posed significant challenges to later efforts at canonization and interpretation.

Disputed Pauline epistles

Paul of Tarsus, one of the most influential figures in early Christianity, is traditionally credited with writing 13 letters (epistles) found in the New Testament. However, modern scholarship has identified significant differences in style, vocabulary, and theological emphasis among these letters, leading to the division of Paul’s letters into three categories: undisputed, disputed, and pseudonymous.

The undisputed epistles — Romans, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, and Philemon — are widely regarded as authentic writings of Paul. These letters exhibit a consistent style and theological focus, reflecting Paul’s missionary activities and concerns regarding early Christian communities.

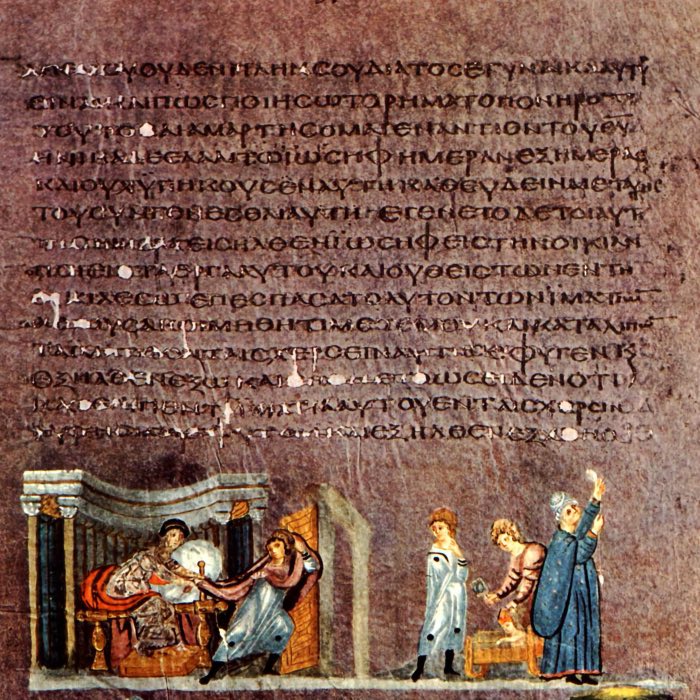

Papyrus 46, one of the oldest New Testament papyri, showing 2 Cor 11:33–12:9. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

In contrast, the authorship of Colossians and 2 Thessalonians is disputed. While these letters contain Pauline elements, they also exhibit notable differences in vocabulary and theological themes, particularly regarding eschatology (the study of end times) and ecclesiology (the structure of the church). Some scholars argue that they may have been written by close disciples of Paul, who sought to preserve and expand his teachings in a changing context.

The pastoral epistles — 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus — are widely regarded as pseudonymous. These letters address issues of church organization, leadership, and orthodoxy that became prominent in the early 2nd century, well after Paul’s lifetime. The vocabulary and style differ significantly from Paul’s authentic letters, and the emphasis on hierarchical church structure reflects a later stage in Christian development. Most scholars believe these letters were written by later authors seeking to lend apostolic authority to emerging ecclesiastical norms.

The general epistles: James, Peter, and Jude

Several general epistles, also known as Catholic epistles, are attributed to prominent early Christian figures such as James (the brother of Jesus), Peter, and Jude. Among these, the Epistle of James and 1 Peter are subject to scholarly debate regarding their authenticity.

The Epistle of James is traditionally attributed to James, the leader of the Jerusalem church and the brother of Jesus. However, its polished Greek style and lack of direct reference to key events in the life of Jesus suggest that it may have been composed by a later writer familiar with Hellenistic literary conventions. Despite these doubts, some scholars maintain that it may reflect genuine teachings of James, later compiled and edited by others.

1 Peter, traditionally attributed to the apostle Peter, also exhibits a high level of Greek sophistication, inconsistent with what might be expected of a Galilean fisherman. Additionally, the letter addresses a Christian audience experiencing persecution, a context more consistent with the late 1st century than with Peter’s lifetime. While some scholars argue that Peter could have employed a secretary to compose the letter, others view it as a pseudonymous work written by a follower of Peter.

2 Peter is almost universally regarded as pseudepigraphal. Its significant stylistic differences from 1 Peter, heavy reliance on Jude, and references to the delayed return of Christ (parousia) suggest a 2nd-century origin. Early church leaders were slow to accept 2 Peter into the canon, further supporting the view that it was a later composition.

The Epistle of Jude, while short, presents its own challenges. It references apocryphal Jewish works such as the Book of Enoch and the Assumption of Moses, raising questions about its theological outlook and audience. While its authorship by Jude, the brother of Jesus, is traditionally accepted, some scholars view it as a later work that incorporates earlier Jewish traditions.

The Gospels: Anonymous works with traditional attributions

The four canonical Gospels — Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John — are anonymous works, with their traditional attributions to apostolic figures emerging in the 2nd century. Modern scholarship has challenged these attributions, emphasizing that the Gospels were likely composed by educated Greek-speaking Christians rather than by the apostles themselves (if they actually existed).

Mark, generally considered the earliest gospel, is traditionally associated with John Mark, a companion of Peter. However, the gospel itself does not claim this authorship, and its portrayal of Jesus’ disciples is often critical, suggesting that it was written by someone outside the immediate circle of the apostles.

Matthew and Luke both incorporate large portions of Mark and a hypothetical source known as “Q,” a collection of Jesus’ sayings. The traditional attribution of Matthew to the tax collector and apostle of the same name is questioned due to the gospel’s reliance on Mark, suggesting that the author was not an eyewitness but a later interpreter of earlier traditions.

Luke is traditionally attributed to a companion of Paul, but the gospel’s prologue and its sequel, Acts, suggest that it was written by a well-educated historian addressing a Greek-speaking audience. While some scholars accept the possibility that Luke was a historical figure associated with Paul, others emphasize the theological agendas present in Luke-Acts, indicating a later composition.

John, the most theologically developed gospel, is traditionally ascribed to the apostle John. However, its distinct style and theological outlook have led many scholars to conclude that it was written by members of a Johannine community rather than by John himself. The gospel’s late date (c. 90–110 CE) further supports this view.

Revelation: A unique case

Revelation, attributed to John of Patmos, presents a special case in the discussion of authorship. While early Christian tradition associated the author with John the apostle, modern scholars distinguish between the two figures due to differences in style and content compared to the Gospel of John. Revelation’s apocalyptic imagery and symbolic language reflect a genre that was common in Jewish and early Christian literature, making it difficult to assess its historical authorship. Despite these uncertainties, Revelation is generally considered an authentic product of early Christian prophetic tradition.

Summary: Authenticity of New Testament scriptures

The following table summarizes the scholarly consensus on the authenticity of the New Testament scriptures, including their traditionally attributed authors and estimated dates of composition:

| Scripture | Author | Year (CE) | Authorship status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Romans | Paul | 55–58 | Authentic |

| 1 Corinthians | Paul | 53–54 | Authentic |

| 2 Corinthians | Paul | 55–56 | Authentic |

| Galatians | Paul | 48–49 | Authentic |

| Philippians | Paul | 60–62 | Authentic |

| 1 Thessalonians | Paul | 50–51 | Authentic |

| Philemon | Paul | 60–61 | Authentic |

| Colossians | Possibly a follower of Paul | 60–70 | Disputed |

| 2 Thessalonians | Possibly a follower of Paul | 50–60 | Disputed |

| Ephesians | Unknown, attributed to Paul | 70–90 | Pseudonymous |

| 1 Timothy | Unknown, attributed to Paul | 100–120 | Pseudonymous |

| 2 Timothy | Unknown, attributed to Paul | 100–120 | Pseudonymous |

| Titus | Unknown, attributed to Paul | 100–120 | Pseudonymous |

| Hebrews | Unknown | 60–100 | Disputed |

| James | Possibly James, brother of Jesus | 60–90 | Disputed |

| 1 Peter | Possibly a disciple of Peter | 80–100 | Disputed |

| 2 Peter | Unknown | 100–120 | Pseudonymous |

| Jude | Possibly Jude, brother of Jesus | 70–110 | Disputed |

| Mark | Unknown, attributed to John Mark | 65–70 | Anonymous, traditionally attributed |

| Matthew | Unknown, attributed to Matthew | 80–90 | Anonymous, traditionally attributed |

| Luke | Unknown, attributed to Luke | 80–100 | Anonymous, traditionally attributed |

| John | Unknown, attributed to John | 90–110 | Anonymous, traditionally attributed |

| Acts | Unknown, attributed to Luke | 80–100 | Anonymous, traditionally attributed |

| Revelation | John of Patmos | 90–100 | Disputed |

Out of the 27 books in the New Testament, only 7 are widely accepted as authentic (written by their traditionally attributed authors). The remaining 20 books are either disputed or considered pseudonymous. Thus, the majority of New Testament books were likely not authored by the figures to whom they are traditionally attributed, reflecting a common feature of literary practice in antiquity, where pseudepigraphy was often used to lend authority to religious and philosophical works.

Conclusion

While traditional Christian doctrine holds that the New Testament books were written by apostles and their close associates, critical scholarship suggests that about half of these books are pseudepigraphal or editorially reworked. Of the 27 books, only around 7 are widely accepted as authentic in terms of their traditional attribution, with the remaining books either disputed or considered pseudonymous. Forgery and editorial rewriting were common practices in antiquity, particularly within religious and philosophical circles, as a means to lend authority to particular teachings or ideas. The New Testament reflects this broader cultural context, where writing in the name of revered figures was not seen as fraudulent in the modern sense but rather as a legitimate way to promote doctrinal continuity and orthodoxy.

References and further reading

- Bart D. Ehrman, Forged: Writing in the name of God – Why the Bible’s authors are not who we think they are, 2011, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780062012616

- Metzger, Bruce M., The canon of the New Testament: Its origin, development, and significance, 1997, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0198269540

- Finkelstein, I., & Silberman, N. A., The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, 2002, Free Press, ISBN: 978-0684869131

- Thompson, Thomas L., The mythic past: Biblical archaeology and the myth of Israel, 2000, Basic Books, ISBN: 978-0465006496

- Richard Carrier, On the historicity of Jesus – Why we might have reason for doubt, 2014, Sheffield Phoenix Press, ISBN: 9781909697492

- Richard C. Carrier, Proving History: Bayes’s Theorem and the Quest for the Historical Jesus, 2012, Prometheus Books, ISBN: 978-1616145590 Doherty, Earl, Lenz, Arnher E. (translator), The Jesus Puzzle: Did Christianity Begin with a Mythical Christ?, 2003, Angelika Lenz Verlag, ISBN: 978-3933037268

- Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, 2013, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780062206442

- Price, Robert M., The Christ-Myth Theory and Its Problems American Atheist Press, 2012, ISBN: 978-1578840175

comments