Christianity: A syncretic religion in historical context

Christianity, as one of the world’s major religions, has long been the subject of extensive academic inquiry. Its origins, core teachings, and historical development have been studied through various disciplinary lenses, including theology, history, anthropology, and comparative religion. Scholars have debated how Christianity emerged, the nature of its earliest communities, and how it evolved into an institutionalized faith. In this post, we examine current scholarship on Christianity, focusing on its syncretic nature and historical context.

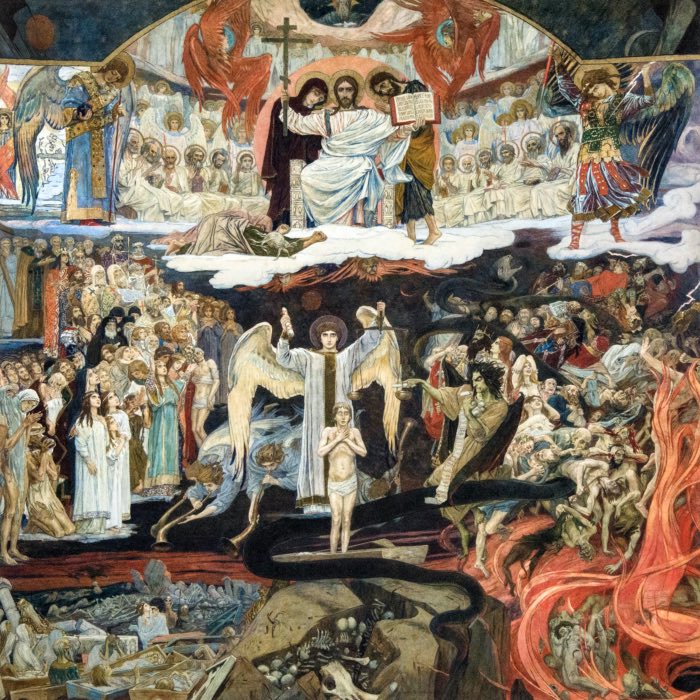

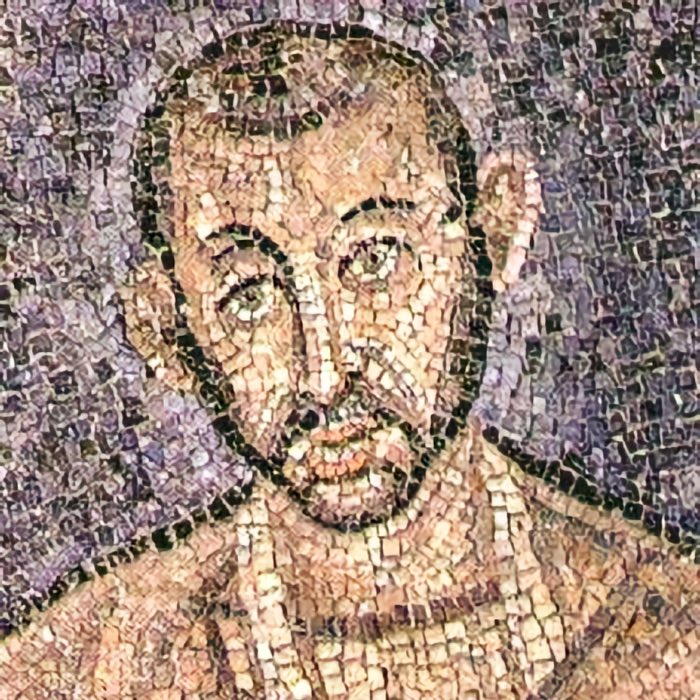

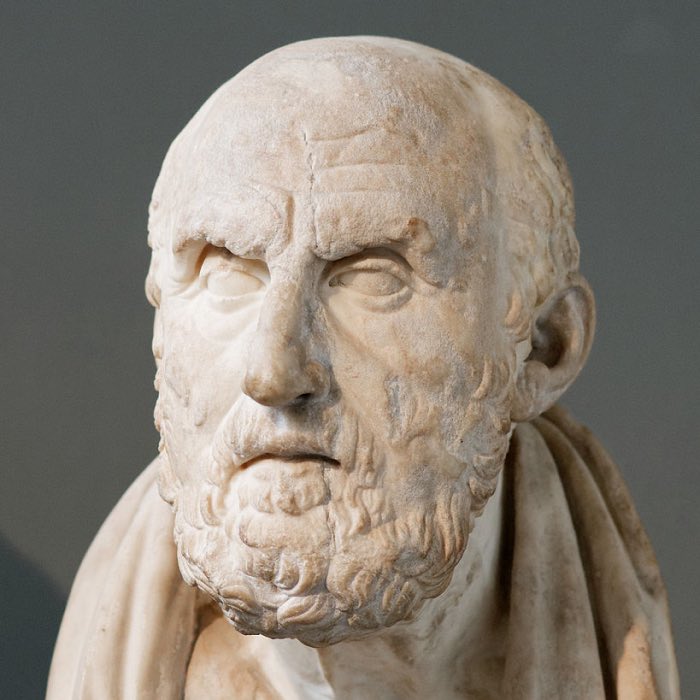

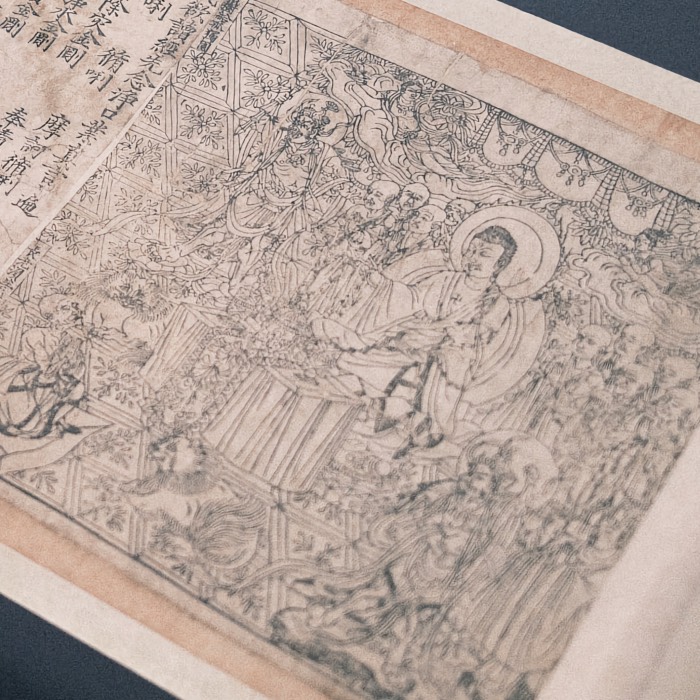

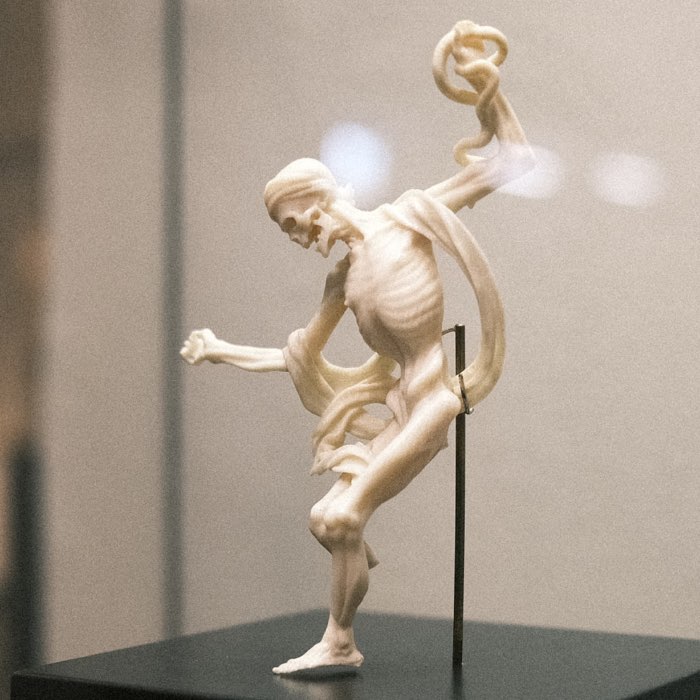

Jesus Christ - detail from Deesis mosaic, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (today: Istanbul). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Defining Christianity

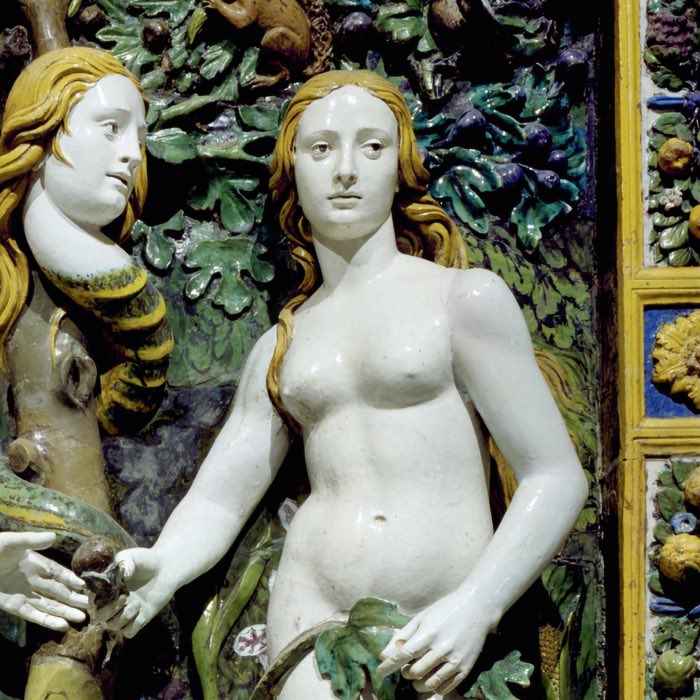

Christianity is traditionally defined as a monotheistic religion centered on the life, teachings, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth. Its earliest adherents, known as Christians, regarded Jesus as the Messiah prophesied in Jewish scripture and the Son of God who brought salvation to humanity. However, beyond this basic definition, Christianity’s nature and identity have been shaped by diverse theological interpretations, cultural influences, and historical developments. From its earliest formation as a sect within Second Temple Judaism to its establishment as the dominant religion of the Roman Empire, Christianity underwent significant transformations, adapting to new contexts and challenges.

Modern scholarship has expanded the definition of Christianity to account for its diversity and complexity. Different denominations and movements have emerged over the centuries, each interpreting core Christian doctrine in distinct ways. Today, Christianity encompasses a wide range of traditions, including Catholicism, Orthodoxy, and various Protestant denominations.

Christianity’s origins: From Jewish sect to syncretic faith

Jewish roots

The earliest form of Christianity emerged within the Jewish milieu of the Second Temple period. The figure of Jesus, as narrated in the Gospels, is portrayed as a Jew whose earliest followers, including the apostles, identified with Jewish traditions. Many scholars argue that early Christianity was initially viewed as a reform movement within Judaism, aiming to reinterpret the Torah and prophetic texts in light of the teachings and resurrection of this figure.

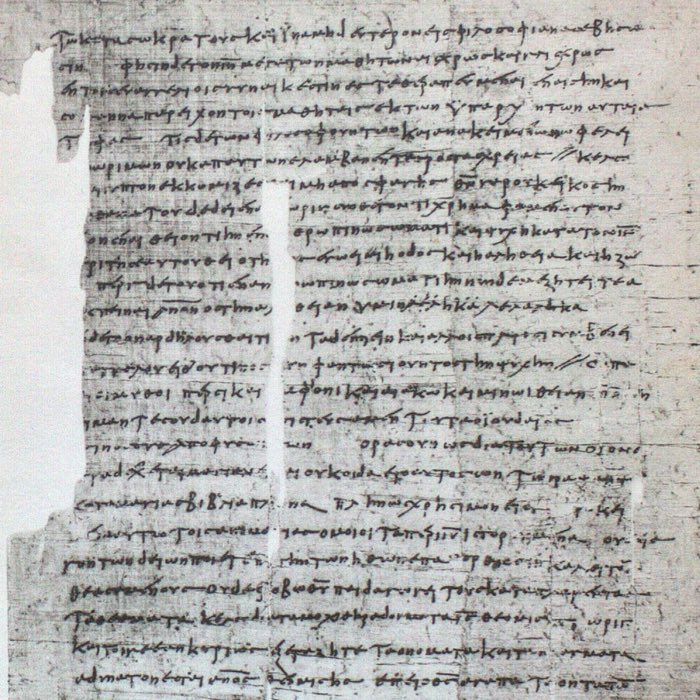

Early Christian texts, particularly the letters of Paul and the synoptic Gospels, reflect this Jewish heritage. They frequently reference Jewish scriptures, traditions, and concepts, framing Jesus as the fulfillment of Messianic prophecies. However, as the movement expanded beyond Palestine and began attracting Gentile converts, tensions arose between Jewish and Gentile Christians regarding adherence to Jewish law.

Syncretism with Hellenistic and Roman elements

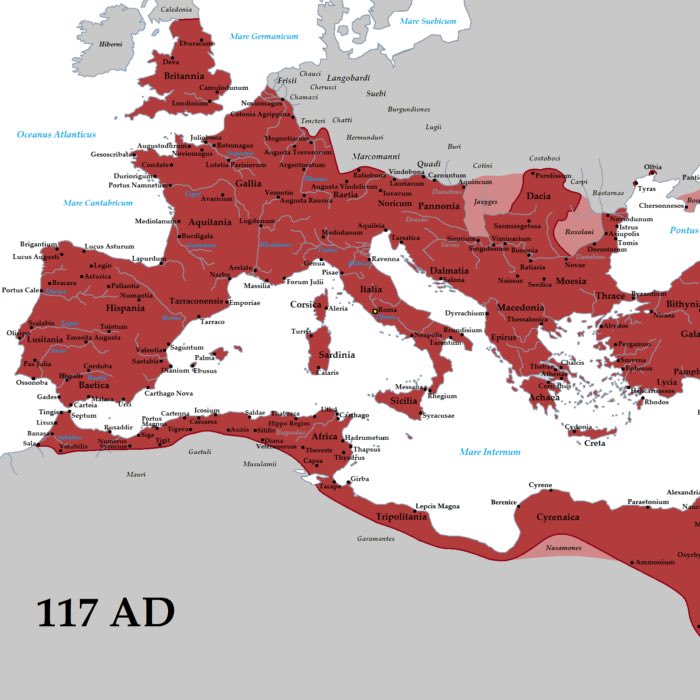

While Christianity began as a Jewish sect, it rapidly absorbed elements from the broader Hellenistic and [Roman](/weekend_stories/told/2025/2025-01-22-roman_empire/) cultural milieu. The spread of Christianity through the Greco-Roman world brought it into contact with various philosophical schools, religious traditions, and cultural practices. This interaction led to the incorporation of Hellenistic philosophical concepts, such as logos theology, and the adaptation of certain rites and symbols from Greek mystery cults.

According to scholars like Richard Carrier, early Christianity may have functioned as a syncretic mystery cult. Mystery cults in the ancient Mediterranean world typically revolved around secret rites, initiatory practices, and the promise of personal salvation through participation in the death and rebirth of a savior figure. Carrier argues that Christianity fits within this pattern, with its emphasis on baptism, the Eucharist, and the death and resurrection of the figure of Jesus as described in the Gospels.

From an apocalyptic sect to a distinct religion

To further examine Christianity’s emergence as an apocalyptic movement within the Jewish community, the following articles will discuss specific aspects of its early development:

Jewish context:

- Scriptures rewritten: How pseudepigraphy shaped the New Testament

- How Paul’s epistles engineered early Christianity

- The mythological character of the Gospels: A critical examination of Richard Carrier’s theories

- Richard Carrier and the historicity of Jesus: Was Christianity born from a mystery cult?

- Philo of Alexandria’s logos concept and its potential influence on the development of the Jesus narrative

- Enoch: Another exemplar for the Jesus narrative?

- Why did Jewish apocalypticism culminate in the 1st century CE?

- The role of sacrificial blood rituals in Judaism and its reinterpretation in Christianity

- The resurrection of Jesus as a mythological tool for early Christian legitimization

Doctrinal evolution and institutional frameworks:

- How Jesus became God: Exploring Bart D. Ehrman’s thesis on the development of Christian belief in Jesus’s divinity

- Twelve Apostles, one myth: Debunking the foundation of institutional Christianity

- Speculating on Lazarus as the beloved disciple of Jesus

- Jesus’ apocalyptic message: Did the apostles spread a narrower version of Jesus’ teachings?

Cultural interactions and community practices:

- The spread of early Christianity

- The life and practices of early Christians

- Dura-Europos: One of the earliest Christian house churches and oldest synagogues in a religious melting pot

- The Apostolic Council: A turning point in the expansion of early Christianity

- Why Jews did not believe in Jesus: Historical and theological roots of the Jewish-Christian divergence

- How much does Christianity actually differ from Judaism?

- Faith or order? The true reasons behind Roman persecution of Christians

- The cult of Mithras and Roman mystery religions: Christianity in a spiritual melting pot

Early evolution of rituals, symbols, and hierarchies:

- The Didache: The blueprint of a developing church and the birth of ritualized Christianity

- Trinity: An example of how Christianity engineered itself beyond its original scriptures

- The birth of Christian priesthood and hierarchical structures: From egalitarian communities to institutionalized religion

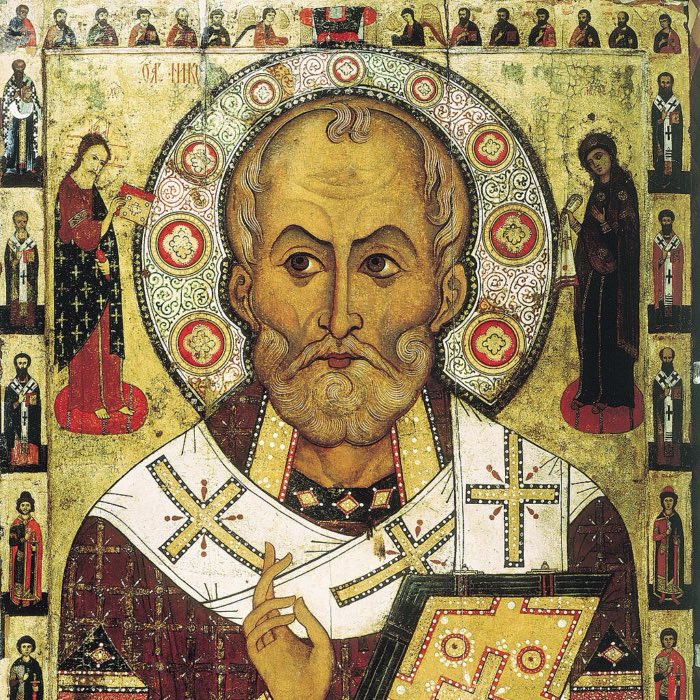

- Earliest depictions of Jesus

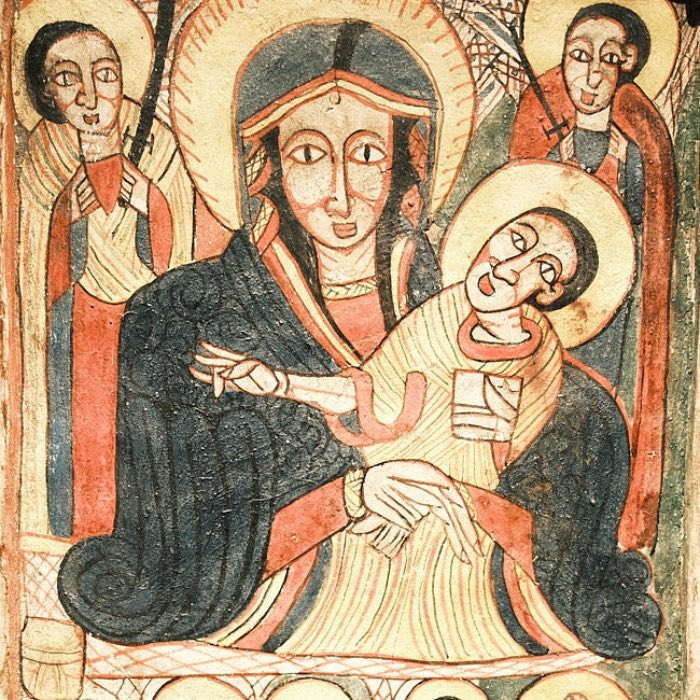

- Mother of God cult in the Roman Empire and its transformation into Marian devotion

The beginnings of a separate identity:

- Origen of Alexandria: Elevating Christianity from a mystery clut to systematic theology

- Theology of Augustine of Hippo

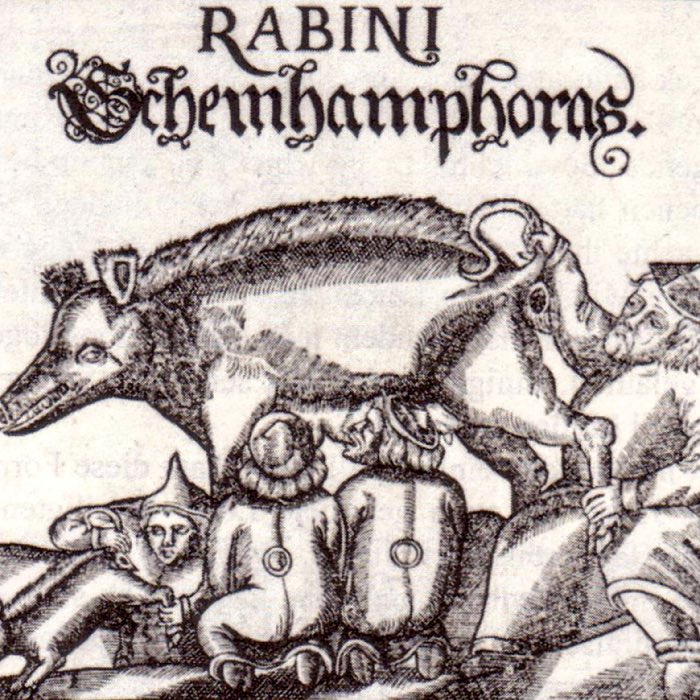

- Foundation of Christian antisemitism and the role of Augustine of Hippo

- Dogma and its role in Christian orthodoxy

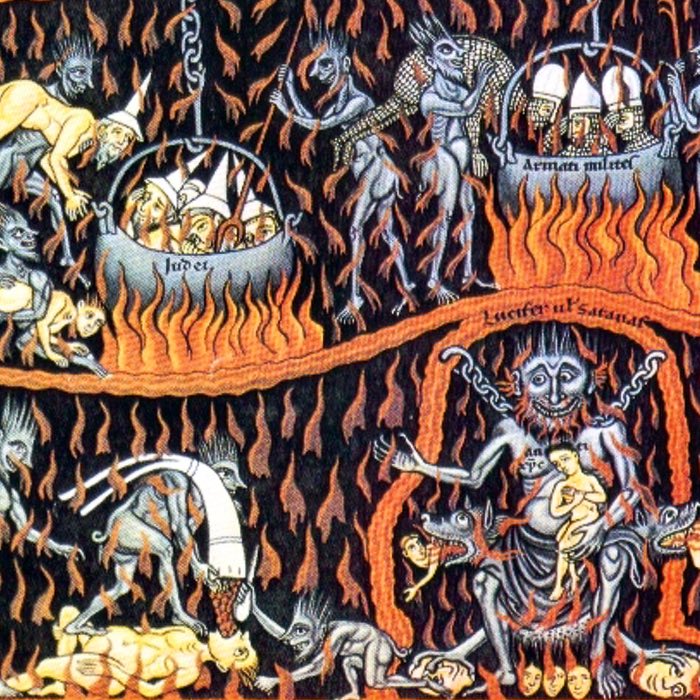

- The concept of hell and its instrumentalization by the Church

Finally, this post examines the evolution of Christian theology, tracing its transformation from an apocalyptic Jewish sect into a structured religious system deeply rooted in Hellenistic and Roman intellectual traditions.

Christianity as a mystery cult

Some scholars, such as Richard Carrier, have proposed that early Christianity shared significant similarities with ancient mystery cults, suggesting that it functioned as a syncretic religious movement that incorporated elements from various cultural traditions. Carrier’s hypothesis challenges traditional views of Christianity’s origins and development, positing that it emerged as a mystery cult within the Greco-Roman world. In the following, we briefly outline Carrier’s theory and its implications for understanding Christianity’s early history.

Core features of a mystery cult

Carrier’s hypothesis posits that early Christianity shared several defining features of ancient mystery cults:

- Initiation rites: Baptism served as the primary initiation ritual in early Christianity, symbolizing the believer’s participation in Jesus’s death and resurrection.

- Secret teachings: While early Christianity emphasized public preaching, certain theological concepts were only fully explained to initiated members, reflecting the esoteric nature of mystery cults.

- Savior figure: Central to mystery cults was the figure of a dying-and-rising god, such as Osiris or Mithras. Carrier suggests that Jesus originally functioned as a celestial savior figure whose death and resurrection took place in a mythical realm rather than historical Palestine.

It is within this framework that Carrier interprets the Gospels and early Christian texts, viewing them as mythological narratives designed to convey spiritual truths rather than historical events. According to Carrier, the Gospel accounts of Jesus’s life, teachings, and miracles should be read as symbolic expressions of theological concepts rather than factual records.

Evolution from imaginary to historical Jesus

One of Carrier’s more controversial claims is that Jesus was initially conceived as a purely celestial being. Early Christians, according to Carrier, believed in a heavenly Jesus who revealed divine truths through visions and hidden messages in Jewish scriptures. Over time, as Christianity grew and sought to establish its legitimacy, this celestial Jesus was historicized into a real person who lived and preached in Galilee.

Carrier uses the term “euhemerization” to describe this process, drawing on the example of Euhemerus, a Greek writer who argued that gods were originally historical figures later deified. In Carrier’s view, the Gospels represent the final stage of this process, transforming a mythic savior into a historical teacher and prophet.

Criticisms of Carrier’s hypothesis

While Carrier’s hypothesis has sparked interest, it remains a minority view among scholars. Some critics argue that Carrier overemphasizes parallels with mystery cults and may underplay the distinctiveness of early Christian beliefs. Nevertheless, Carrier’s interpretation has gained traction among those advocating for a broader, more syncretic understanding of Christianity’s origins. Scholars who uphold the historicity of Jesus typically rely on limited and only indirect evidence, which leaves room for alternative hypotheses like Carrier’s to be explored.

Implications: Myth vs. history in early Christianity

Carrier’s work has significantly contributed to ongoing debates about the nature of early Christianity and the interplay between myth and history in the Gospel narratives. If true, his theory would necessitate a radical reimagining of Christianity’s origins, framing it as a syncretic mystery cult rather than a historical religion founded by an earthly-divine figure. I think, Carrier’s hypothesis still leaves room for an actual historical Jesus to have existed. However, it challenges traditional Christian narratives and invites a reevaluation of the Gospels’ theological and historical significance, being seen as mythological rather than historical accounts of any possible historical figure of Jesus.

Core teachings

Despite debates about its origins, certain core teachings of Christianity can be identified in its earliest texts:

- Monotheism: Christianity inherited Jewish monotheism but reinterpreted it through the lens of Jesus’s divinity and the concept of the Trinity.

- Salvation through faith: Central to Paul’s writings is the idea that salvation is granted through faith in Jesus Christ, rather than adherence to the Mosaic law.

- Ethical teachings: Early Christian ethics emphasized love, compassion, and humility, drawing on both Jewish and Hellenistic moral traditions.

- Eschatology: Early Christians believed in the imminent return of Jesus and the establishment of God’s kingdom, a belief that shaped their worldview and missionary zeal.

Christianity’s claim to absolute truth and its historical consequences

Beyond these core teachings, Christianity also developed a self-view of being the sole holder of absolute truth, which had far-reaching historical consequences. From its early stages, Christians viewed their faith as the ultimate revelation of divine truth, which naturally excluded those who did not accept or convert to it. This exclusivist stance fostered a dualistic worldview that categorized non-believers as being outside the realm of salvation.

Although this notion is not explicitly found in the teachings transmitted by the Gospels, it became an integral part of Christianity’s identity over time. This self-perception of superiority, combined with the belief in possessing the ultimate truth, justified actions such as forced conversions, the legitimization of violence, and the suppression of dissent. These tendencies became particularly pronounced following Constantine’s endorsement of Christianity in the early 4th century, which marked the beginning of a close alliance between the Church and secular power.

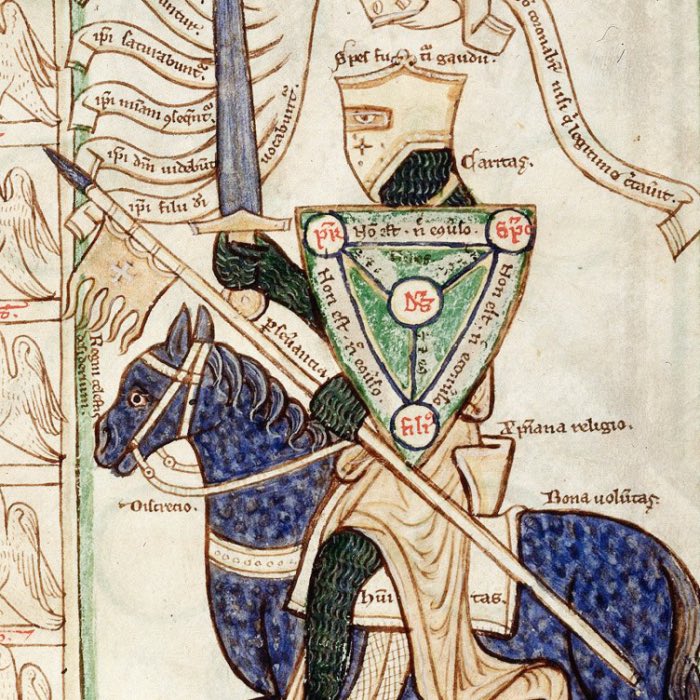

The institutionalized Church, once persecuted, became a dominant force, often using its newfound power to enforce orthodoxy and eliminate rival interpretations. The conviction of holding absolute truth provided a rationale for numerous historical events, including the Crusades, the Inquisition, and missionary efforts that often involved coercion. While many Christian movements have since repudiated such practices, the historical legacy of these actions remains a critical aspect of Christianity’s development as a global religion.

Thus, alongside its core ethical and spiritual teachings, Christianity’s self-image as the custodian of absolute truth significantly shaped its interaction with the broader world, contributing to its expansion, influence, and, at times, its darker historical episodes.

Historical overview of Christianity

The following timeline provides a chronological overview of key events and developments in the history of Christianity:

- c. 50: First written references of figure called ‘Jesus’

Paul writes the first written testimonies of a messianic figure, Jesus, likely including letters such as 1 Thessalonians, Galatians, and Corinthians. First indications that a missionary branch of Judaism within the Roman Empire gave rise to a group believing in a heavenly Messiah. - c. 50: Apostolic Council

This (alleged) early meeting of Christian leaders aimed to resolve key doctrinal disputes regarding whether Gentile converts to Christianity were required to follow Jewish law, such as circumcision and dietary restrictions. The outcome, which relaxed these requirements, was significant in shaping Christianity as a universal faith distinct from Judaism, facilitating its spread across the Roman Empire and establishing a foundation for later theological developments. - c. 50–60: Paul’s missionary missions

Paul’s missions, traveling extensively across the Roman Empire to regions such as Asia Minor, Greece, and Rome, played a critical role in spreading Christian teachings and establishing the first early Christian communities. His efforts were instrumental in transitioning Christianity from a Jewish sect into a distinct religious movement, emphasizing salvation through faith in Jesus Christ rather than adherence to Jewish law. - c. 64–313: Era of Christian martyrdom

A period of persecution of Christians by the Roman authorities, beginning with the Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE and culminating in the Diocletianic Persecution in the early 4th century. Victims of these period are later venerated as martyrs and saints, contributing to the development of Christian identity and the cult of the saints. - 70: Destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem

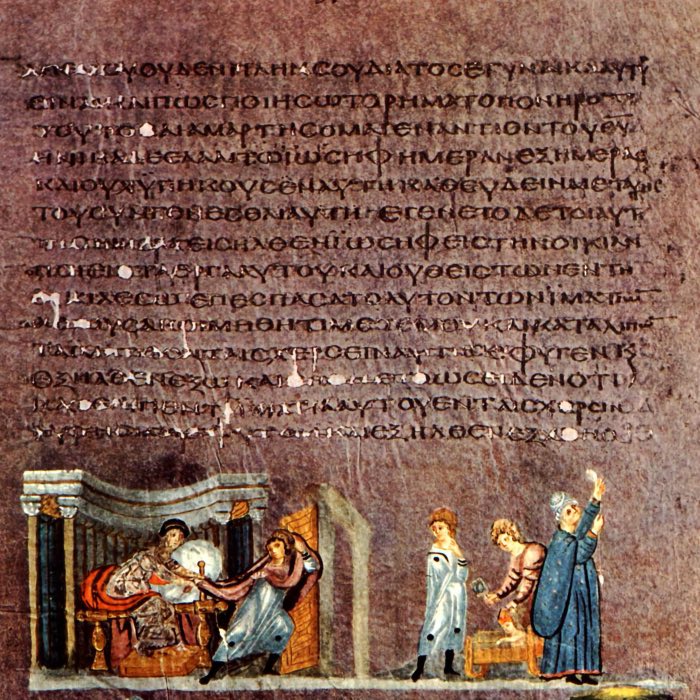

Jews lose a key identity symbol. This event significantly impacted early Christian theology, contributing to the separation from Judaism and the development of a distinct Christian identity. - c. 70–120: The Gospels are written, Jesus is historicized

Composition of additional writings and the four canonical Gospels, and the mythological figure of Jesus is historicized:- 70–75: Gospel of Mark Characterized by its brevity, emphasis on Jesus’ suffering, and portrayal of disciples as misunderstanding his mission.

- 80–85: Gospel of Luke

Characterized by its detailed narrative, focus on social justice, and inclusiveness toward Gentiles. - 80–90: Gospel of Matthew

Characterized by its Jewish orientation, frequent references to Hebrew Scriptures, and depiction of Jesus as the new Moses. - 90–100: Gospel of John

Characterized by its theological depth, emphasis on Jesus’ divinity, and use of symbolic language. - Other gospels not canonized:

- c. 120: Gospel of Thomas

A collection of 114 sayings attributed to Jesus, emphasizing mystical knowledge. - c. 140: Gospel of Peter

Known for its distinctive resurrection account and early docetic tendencies. - c. 150: Gospel of Mary Magdalene Highlights Mary Magdalene’s role and includes gnostic themes.

- c. 180: Gospel of Judas

Presents Judas Iscariot in a more positive light and reflects Gnostic interpretations.

- c. 120: Gospel of Thomas

- c. 95: Book of Revelation

Revelation of John: An apocalyptic text rich in symbolic imagery, addressing early Christian persecution and offering hope for the faithful. - c. 100: The Didache

The Didache can be interpreted as a blueprint of a developing church hierarchy and the birth of ritualized Christianity. - c. 144: Marcion of Sinope

A controversial figure who rejected the Hebrew Bible and advocated for a radical reinterpretation of Christian theology. His teachings, which emphasized the dichotomy between the Old and New Testaments, led to his excommunication and the formation of the Marcionite sect (or Marcionism). - c. 150: Valentinus

A prominent Gnostic teacher who developed a complex cosmology and theology, blending Christian, Jewish, and Hellenistic elements. His teachings influenced early Christian thought and contributed to the development of Gnostic Christianity. His movement, known as Valentinianism, was later declared heretical by the emerging orthodox Church. - c. 184–253: Origen of Alexandria

An influential early Christian theologian and scholar, Origen made significant contributions to biblical exegesis, theology, and philosophy. He is best known for his allegorical interpretation of Scripture and his work On First Principles, which laid the foundation for later Christian doctrinal development. His ideas on the pre-existence of souls and universal salvation were controversial, influencing Christian thought for centuries while also leading to posthumous condemnation by later Church authorities. - 2nd century: Peak of Gnosticism

A diverse religious movement characterized by esoteric knowledge, dualism, and the belief in a transcendent God. Gnosticism influenced early Christian thought and produced a wide range of texts, including the Nag Hammadi Library, which offered alternative perspectives on Jesus, salvation, and the nature of reality. However, Gnostic beliefs were eventually declared heretical by the orthodox Church, leading to their suppression and marginalization. - c. 230: Dura-Europos house church

One of the earliest known Christian house churches, offering valuable insights into early Christian worship practices, community life, and the transition from informal gatherings to organized religious institutions. - c. 248: Contra Celsum

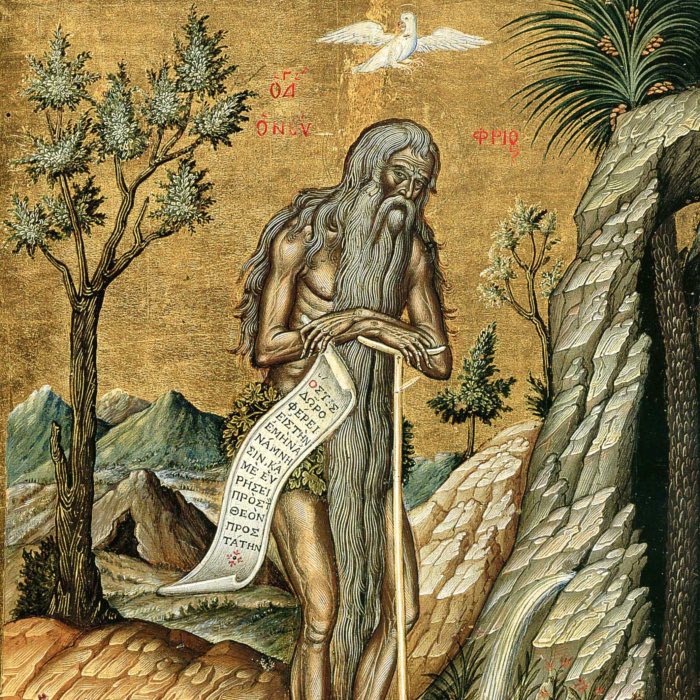

Origen’s response and the irony of survival. - 3rd–4th century: The Desert Fathers

A group of early Christian hermits, monks, and ascetics who lived in the Egyptian desert. Their practices of severe self-discipline and solitary prayer laid the foundations for Christian monasticism. The Desert Fathers’ teachings, compiled in texts such as the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, greatly influenced later Christian spirituality and the development of communal monastic orders. - 313: Edict of Milan

Christianity is no longer persecuted in the Roman Empire. - 314: Council of Ancyra This early council issued one of the first known Church canons condemning homosexual acts, equating them with other sexual sins and prescribing penance for those who engaged in them.

- c. 325–337: Constantine the Great

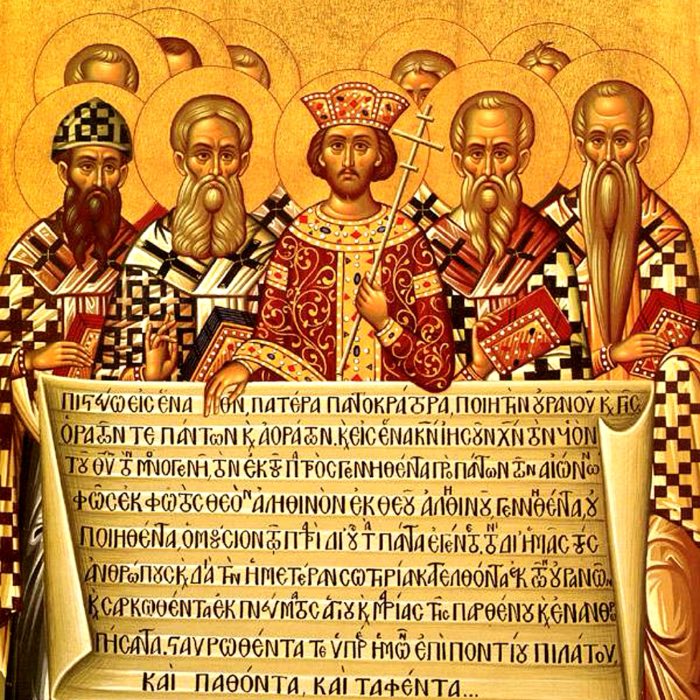

First Roman emperor to convert to Christianity, instrumental in legitimizing and promoting the faith throughout the empire, and convened the First Council of Nicaea. - 325: Council of Nicaea

Council defining the (politically motivated) creed and Jesus’ divinity. - 354–430: Augustine of Hippo

One of the most influential figures in Western Christianity and philosophy. His works, such as Confessions and The City of God, shaped Christian theology, particularly in areas such as original sin, grace, and predestination. Augustine’s thought deeply influenced the development of medieval scholasticism and the Protestant Reformation, making him a pivotal bridge between classical philosophy and Christian doctrine. - 380: Edict of Thessalonica

Theodosius I declares Christianity the state religion. - 381: First Council of Constantinople

The council reaffirmed the Nicene Creed and addressed theological controversies surrounding the Holy Spirit, further solidifying Christian orthodoxy. - 390: Edict of Theodosius I

Theodosius I issues a law prescribing death by burning for male homosexual acts. This law reflected a harsh shift in legal treatment of homosexuality under Christian influence. - 391: Destruction of the Serapeum of Alexandria

Christianity’s shift from persecuted to persecutor. - c. 400—814: Formation of various Christian branches

- Christians in India (traditionally traced to c. 52)

- Copts (emerged c. 1st–4th century)

- Syriac Church (developed c. 2nd–3rd century)

- Armenian Church: The first national church in Christian history (established c. 301)

- Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (established c. 4th century)

- The Kingdom of Iberia: Early Christian civilization in the Caucasus (adopted Christianity c. 4th century)

- Byzantine orthodoxy (formalized c. 5th–6th century)

- Church of the East (emerged c. 5th century)

- Nubian Christianity (flourished c. 6th–14th century)

- c. 400—814: The Migration Period

Fall of the Western Roman Empire (476). This event led to significant political fragmentation in Western Europe and paved the way for the rise of the medieval kingdoms and the spread of Christianity (5th–10th century) among the Germanic tribes. - c. 400–461: Pope Leo I

The architect of papal primacy, asserting the Pope’s authority over the Church and secular rulers. - 451: Council of Chalcedon

Defined the dual nature of Christ (both human and divine) and led to significant schisms, including the formation of Oriental Orthodox Churches. - c. 525: Formation of the Christian calendar Shift from the Roman calendar to the Christian calendar (Anno Domini, AD)

- 527–565: Justinian I

Brief restoration of the Roman Empire. - 529: Closure of the Academy in Athens

Emperor Justinian I ordered the closure of the Academy in Athens, which was considered the last stronghold of classical philosophy. This event marked a significant shift in intellectual history, symbolizing the dominance of Christian theology over ancient Greek philosophical traditions and the end of the ancient classical era. - 529 CE – Code of Justinian

Emperor Justinian I’s legal reforms explicitly criminalized homosexual acts, defining them as contrary to divine law and nature. The code prescribed severe punishments, including execution, and linked homosexual behavior to natural disasters and divine retribution. - 570–632: Muhammad

Muhammad, founder of Islam, whose teachings and leadership transformed the Arabian Peninsula both religiously and politically. The rapid expansion of Islamic empires after his death led to significant interactions with and influences on Christian territories. - 7th century: Islamic conquests of formerly Christian/Roman territories

Following the rise of Islam, the Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphates rapidly expanded into territories that were once part of the Christian Roman Empire, including the Levant, North Africa, and the Iberian Peninsula. These conquests led to significant cultural and religious exchanges, as well as periods of both conflict and coexistence between Islamic and Christian societies. - 7th-14th century: Christianization attempts of the Far East Christianization attempts of the Far East in the Middle Ages.

- c. 742–814 CE Charlemagne

Charlemagne, King of the Franks and later crowned Holy Roman Emperor, played a crucial role in the spread of Christianity in Western Europe. His military campaigns, political alliances, and patronage of learning contributed to the Carolingian Renaissance and the consolidation of Christian authority in the region. However, his policies also included brutal defeat of his opponents (including Christians) and forced conversions of pagans. - 8th century: Forgery of the Donation of Constantine

A historical lie that bolstered the Church’s claim to temporal power. This document, later exposed as a forgery, granted the Pope control over vast territories and significantly shaped medieval Church authority, influencing relations with secular rulers for centuries. - 1054: The Great Schism

The Great Schism between the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church, marking a significant division in Christian history. - 1096: The pogroms in Speyer, Mainz, and Worms of 1096

The first great Jewish pogrom of the West and the beginning of the Crusades. - 1096–1270: The Crusades

A series of religious wars initiated and conducted in the name of God and Jesus by the Catholic Church, aimed at reclaiming the Holy Land from Islamic rule. These campaigns had significant religious, political, and cultural consequences, including increased tension between Christians and Muslims, as well as lasting impacts on European and Middle Eastern history. - 11th–14th century: Scholasticism

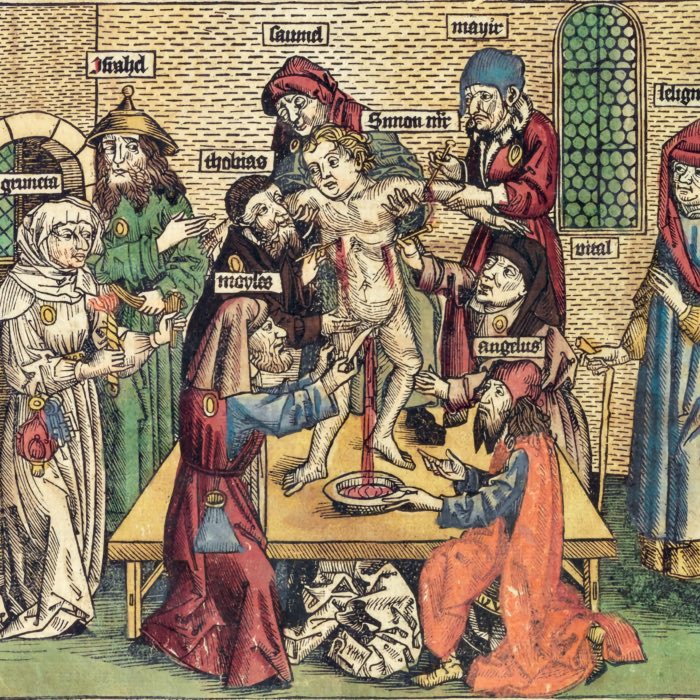

A philosophical and theological movement that sought to reconcile faith and reason, particularly within the Christian tradition. Scholastic thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas, Anselm of Canterbury, and Peter Abelard engaged with classical philosophy, Islamic thought, and Christian theology to address questions of metaphysics, ethics, and the nature of God. Scholasticism played a crucial role in the development of Western intellectual history and influenced subsequent philosophical and theological movements. - 1144: The incident of William of Norwich

The incident of William of Norwich marks the beginning of the Blood Libel myth, which falsely accused. - 1179: Lateran Council III

This ecumenical council officially condemned sodomy (a term broadly used to describe non-procreative sexual acts) as a grave sin. Clerics found guilty of homosexual acts were to be defrocked, and laypeople were to be excommunicated. - 1190: The York Pogrom A violent attack on the Jewish community in York, England.

- 12th century: Rediscovery of ancient philosophical texts

This period saw the reintroduction of Greek and Roman works, primarily through translations from Arabic and Latin. The renewed access to Aristotle, Plato, and other classical thinkers greatly influenced medieval European thought, leading to the development of scholasticism and shaping Christian theology, science, and philosophy for centuries. - 12th–19th century: Era of the Inquisition

The Inquisition: The dark legacy of the Church, including the Medieval Inquisition, Spanish Inquisition, and Roman Inquisition, each with distinct phases and impacts on European society. While the primary focus of the Inquisition was heresy, it also extended to moral offenses, including sodomy. Accusations of homosexual behavior could lead to trials, imprisonment, and execution by burning. - 1215: The Fourth Lateran Council

Institutionalized restrictions on Jews and the origins of systematic anti-Jewish policies. - 1241: Pogrom in Frankfurt

A devastating pogrom culminated in the massacre of a significant portion of the Jewish community in Frankfurt — an event grimly remembered as Judenschlachten (“Slaughter of Jews”) - c. 1260–1327: Meister Eckhart

Eckhart played a significant role in the development of Christian mysticism. His writings, which combined Neoplatonic and Christian thought, emphasized the union of the soul with God and the importance of inner spiritual transformation. Eckhart’s teachings influenced later mystics, including John Tauler and the Friends of God, and contributed to the broader tradition of Western mysticism. - 1290: Expulsion of the Jews from England

This event marks the beginning of a series of expulsions and persecutions of Jewish communities across Europe, driven by religious, economic, and political factors. - 13th century: Mendicant Orders

The rise of the Franciscans and Dominicans, who emphasized poverty and preaching, greatly influencing medieval Christian spirituality. - 1309–1377: Avignon Papacy

A period when the Popes resided in Avignon rather than Rome, leading to tensions and weakening papal authority. - 1349: Pogrom in Frankfurt

Another pogrom in Frankfurt. This event, like the 1241 pogrom, resulted in the massacre of many Jews. - 1378–1417: Western Schism

A division within the Catholic Church with multiple claimants to the papacy, eventually resolved by the Council of Constance. - 1386–1456: John Capistrano

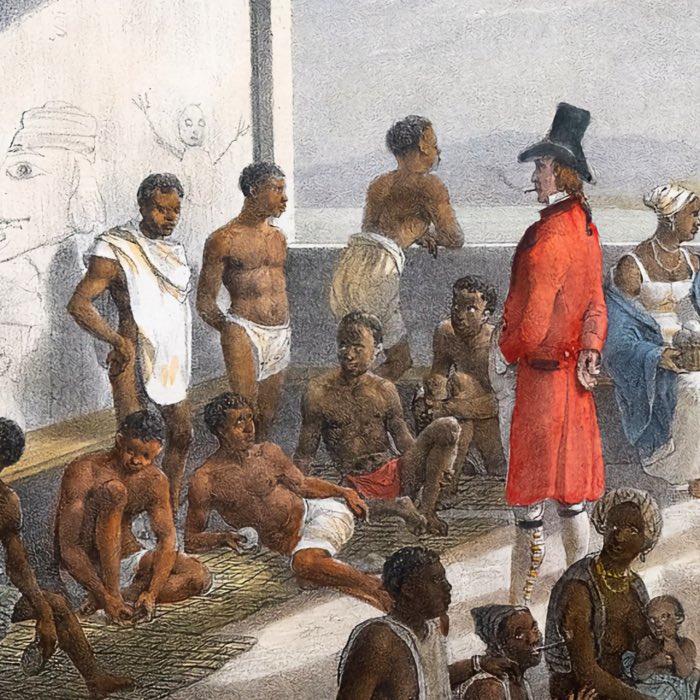

A saint and an anti-Semite, demonstrating the moral decay of the Catholic Church. - 1452: Papal Bull Dum Diversas

Issued by Pope Nicholas V, this bull authorized the Portuguese monarchy to enslave Muslims and other non-Christians, effectively legitimizing the Portuguese slave trade in Africa. - 1453: Fall of Constantinople

The fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire, marking the end of the Byzantine Empire and the beginning of the Ottoman era in the region. - 1455: Papal Bull Romanus Pontifex

Issued by Pope Nicholas V, this bull reinforced the 1452 bull Dum Diversas, granting Portugal the exclusive right to conquer lands and enslave inhabitants, particularly in West Africa. - 1455: Printing of the Gutenberg Bible

The first major book printed using movable type, revolutionizing access to Scripture and spreading literacy. - 1471-1531: The ‘Renassaince Popes’

A period marked by the papacy’s involvement in politics, nepotism, and corruption, including the infamous Borgia family:- 1471–1484: Sixtus IV

- 1492–1503: Alexander VI

- 1503–1513: Julius II

- 1475: Simon of Trento

A prominent example of the Blood Libel myth. - 1483-1546: Martin Luther

The Protestant Reformation: Martin Luther’s 95 Theses and the beginning of the Reformation, leading to the fragmentation of Western Christianity. However, he is also known for his antisemitism, advocacy of violence against peasants and other marginalized groups. - 1492: Expulsion of Jews from Spain and the Sephardic diaspora

The Spanish Catholic Monarchs order the expulsion of Jews, forcing Sephardic communities to migrate to Portugal, North Africa, the Ottoman Empire, and the Netherlands. The Ottoman sultan Bayezid II welcomes Jewish refugees, integrating them into Ottoman commerce and administration. - 1493: Papal Bull Inter Caetera

Issued by Pope Alexander VI, this bull divided the non-Christian world between Spain and Portugal, leading to the colonization and exploitation of indigenous peoples in the Americas and Africa, which included the enslavement of indigenous and African peoples. - 15th–17th century: Witch huntings

The witch hunts of the early modern period, fueled by religious, social, and political factors, led to the persecution a high number of women accused of witchcraft. - 1517–1648: Reformation

A religious and political movement initiated by Martin Luther’s 95 Theses, challenging the authority and practices of the Catholic Church, including indulgences. This period saw the rise of Protestant denominations, significant doctrinal shifts, and widespread social and political upheaval across Europe, ultimately leading to the fragmentation of Western Christianity. - 1533 CE – Buggery Act

Under King Henry VIII, England passed the Buggery Act, making homosexual acts punishable by death. This law reflected the influence of Christian moral doctrine on secular governance. - 1537: Papal Bull Sublimus Dei

Issued by Pope Paul III, it condemned the enslavement of Native Americans, stating that they were rational beings who should not be deprived of liberty. However, it did not explicitly apply to African slavery, which continued under Church-backed colonial rule. - 1545–1563: Council of Trent

Central to the Counter-Reformation, addressing doctrinal and disciplinary reforms within the Catholic Church. The council also reaffirmed the Church’s teachings on sexual morality, emphasizing marriage as a sacrament and condemning all forms of non-marital sexual activity, including homosexuality. - 1545–1648: Counter-Reformation

A movement initiated by the Catholic Church in response to the Protestant Reformation. Spearheaded by the Council of Trent (1545–1563), it aimed to reform internal Church practices, clarify Catholic doctrine, and counter the spread of Protestantism. The Counter-Reformation also led to the rise of new religious orders such as the Jesuits, who played a significant role in missionary work and education. This period was marked by efforts to regain lost territories in Europe and a renewed emphasis on art, architecture, and religious fervor, which influenced the Baroque style. - 1555: Peace of Augsburg

Allowed rulers within the Holy Roman Empire to choose between Lutheranism and Catholicism for their realms, establishing a principle of religious tolerance. - 16th century: Genocide in South America

The Spanish conquest of the Americas led to the decimation of indigenous populations through violence, disease, and forced labor. The Catholic Church played a complex role in this process, with some clergy advocating for the protection of indigenous peoples while others supported the encomienda system (a system of forced labor) and the forced conversion of native populations. The devastating impact of European colonization on indigenous cultures and societies remains a significant historical legacy. - c. 16th century: Christianization attempts of Japan

The arrival of European missionaries in Japan, leading to the spread of Christianity and subsequent persecution of converts. - 1618–1648: Thirty Years’ War

A devastating conflict primarily fought in Central Europe, involving most of the major European powers. Originating as a religious war between Protestant and Catholic states within the fragmented Holy Roman Empire, it evolved into a more general political struggle for power. The war resulted in significant casualties, widespread destruction, and the eventual decline of the Holy Roman Empire’s influence, while also leading to the Peace of Westphalia, which established principles of state sovereignty and religious tolerance in Europe. - 1614–1616: Fettmilch Uprising in Frankfurt

The Jewish community in Fankfurt was violently expelled from the city. The revolt of the guilds was originally directed against the mismanagement of the city council, which was dominated by patricians, but degenerated into the looting of the Judengasse and the expulsion of all Frankfurt Jews. It was finally put down with the help of the Emperor, the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel and the Electorate of Mainz. - 17th century: Baroque era

Baroque as a response to Reformation and restoration of Catholic authority. - 17th–18th century: Enlightenment

A period of new philosophical ideas challenging traditional Christian authority and dogma, shaping modern secular thought. - 1777: Joseph II of Austria’s penal code reform

While not directly from the Church, this reform is notable because it abolished the death penalty for homosexual acts, replacing it with severe imprisonment. The earlier laws in Austria had been influenced by Church doctrine on sexual morality. - 18th–20th century: The Magdalen Laundries scandal

Forced separation of babies and little children from their mothers by Catholic homes in Ireland. - 1815: Congress of Vienna

Papal States after the Congress of Vienna: Reaction and restoration of the papacy. - 1839: Papal Bull In Supremo Apostolatus and the abolition of the slave trade

Pope Gregory XVI condemned the slave trade, yet it had little effect on Catholic nations actively engaged in slavery. - 19th–20th century: Ethnocide of Native American children in Canada

Ethnocide by Catholic residential schools, with involvement from Catholic and other Christian denominations. - 1933–1945: Holocaust

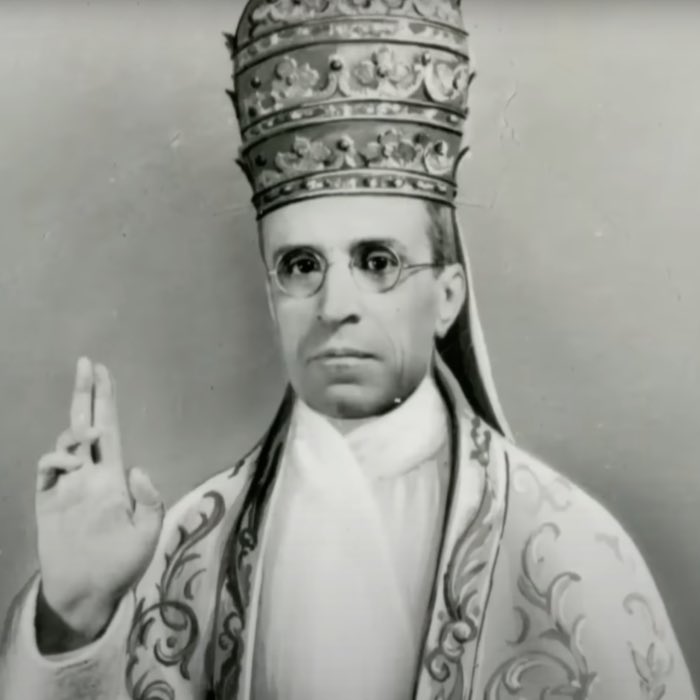

The Catholic Church’s role during the Holocaust remains a topic of significant historical debate. Pope Pius XII, who led the Church during World War II, has been criticized for his perceived silence and lack of public condemnation of the Nazi regime’s systematic extermination of Jews. - 1933–1945: Persecution of homosexuals under the Nazi regime

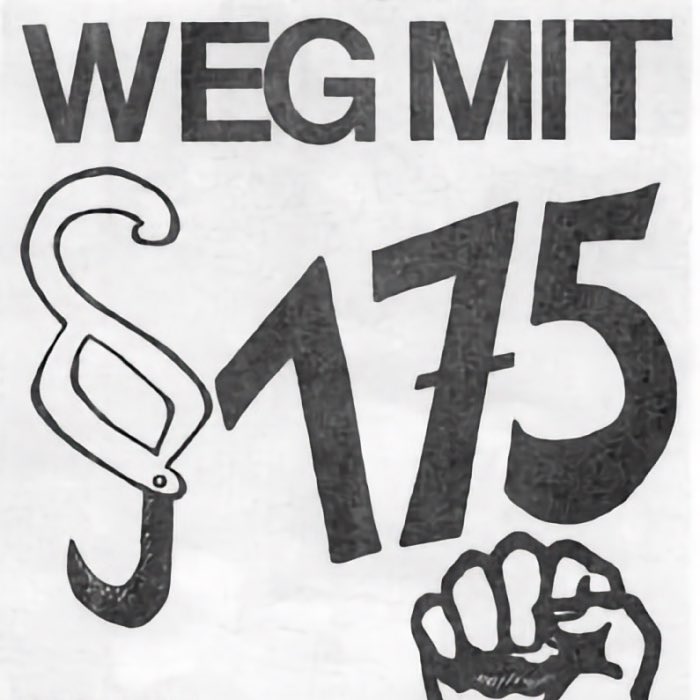

Thousands of homosexuals were persecuted, imprisoned, and executed under the Nazi regime. This systematic oppression can be seen as a consequence of centuries-long condemnation of homosexuality by the Church, which had deeply influenced societal norms and laws in Europe. - Post-1945: Ratlines

Refers to the escape routes used by Nazi officials to flee Europe after World War II, facilitated by some members of the Church. - Post-1945: The Church’s role in the Cold War

Justification of fascists and brutal dictators from before World War II continues. - 1961: The Catholic Church’s declaration on sexual ethics

This Vatican document reaffirmed traditional Christian views on sexual morality, condemning homosexual acts as intrinsically disordered while distinguishing between homosexual orientation and behavior. - 1962–1965: Second Vatican Council

Brought significant modernization to the Catholic Church, including reforms in liturgy, ecumenism, and Church relations with the modern world. - 1980s–present: The HIV/AIDS crisis

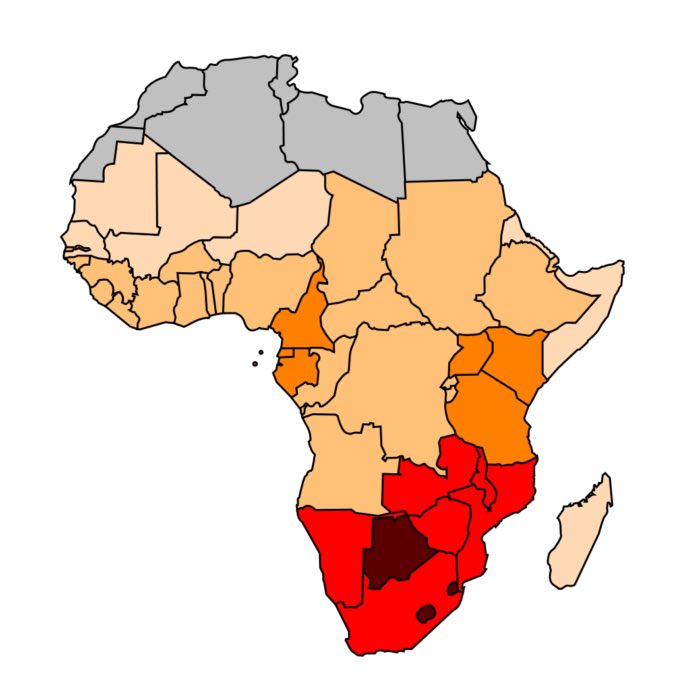

The Catholic Church’s stance on condoms and contraception during the HIV/AIDS crisis has been a source of controversy and criticism. The Church’s opposition to condom use as a means of preventing the spread of HIV/AIDS has been seen as contributing to the epidemic’s severity especially in Africa. - 20th–21st century: The sexual abuse scandal

The sexual abuse of children and the Church’s system of concealment.

Conclusion

The study of Christianity’s origins and development remains a dynamic field of research. While traditional narratives emphasize its roots in Judaism and the historical figure of Jesus, alternative theories, such as Richard Carrier’s hypothesis, propose a more complex and syncretic origin involving mystery cult influences. Regardless of one’s perspective, it is clear that Christianity emerged from a rich cultural and religious milieu, evolving over time into a diverse and multifaceted faith. Its teachings, practices, and historical impact have shaped the course of Western civilization.

Whether one views these impacts as positive or negative, they continue to resonate in contemporary Western societies. The study of Christianity, therefore, offers valuable insights into the complexities of today’s world, particularly regarding religious identity, cultural integration, power dynamics, and the fate of marginalized or victimized groups throughout history. Understanding the syncretic beginnings and subsequent evolution of Christianity not only deepens our grasp of its role in shaping Western civilization and thought but also fosters a more nuanced view of how religious narratives influence modern societal structures and interfaith interactions.

References and further reading

- Richard Carrier, On the historicity of Jesus – Why we might have reason for doubt, 2014, Sheffield Phoenix Press, ISBN: 9781909697492

- Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, 2013, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780062206442

- Bart D. Ehrman, How Jesus became God – The exaltation of a Jewish preacher from Galilee, 2014, Harper Collins, ISBN: 9780062252197

- Dunn, James D.G. The Partings of the Ways: Between Christianity and Judaism and Their Significance for the Character of Christianity. 2006, SCM Press, ISBN: 978-0334029991

- Bruce Manning Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The text of the New Testament – Its transmission, corruption, and restoration, 2005, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195166675

- Bart D. Ehrman, Lost scriptures: Books that did not make it into the New Testament, 2003, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195141825

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- William M. Schniedewind, How the Bible became a book – The textualization of ancient Israel, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521829465

- Richard Friedman, Who Wrote The Bible?, 2019, Simon & Schuster, ISBN: 9781501192401

- Udo Schnelle, Die ersten 100 Jahre des Christentums 30-130 n. Chr. - Die Entstehungsgeschichte einer Weltreligion, 2016, UTB, ISBN: 9783825246068

- Thomas Böhm, Peter Bruns, Wolfram Drews, Michael Durst, Michael Fiedrowicz, Johannes Franzkowiak, Reinhard Meßner, Eckhard Wirbelauer, Gerhard Philipp Wolf, Die Geschichte Des Christentums – Die Zeit des Anfangs (bis 250), 2005, Herder, Ungekürzte Sonderausgabe, Hrsg.: Norbert Brox, Jean-Marie Mayeur, Charles Piétri, Luce Piétri, ISBN: 3-451-29100-2

- Karlheinz Deschner, series: Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums, 10 volumes, Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986ff:

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 1 Die Frühzeit, 1996, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012632

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 2 Die Spätantike, 1996, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499601422

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 3 Die Alte Kirche, 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498012854

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 4 Frühmittelalter - Von König Chlodwig I. (um 500) bis zum Tode Karls ‘des Großen’ (814), 1997, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499603440

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 5 von Ludwig dem Frommen (814) bis zum Tode Ottos III. (1002). 9. und 10. Jahrhundert, 1998, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499605567

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 6 11. und 12. Jahrhundert: Von Kaiser Heinrich II., dem “Heiligen” (1002), bis zum Ende des Dritten Kreuzzugs (1192) (1986)s, 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498013097

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 7 12. und 14. Jahrhundert: Von Kaiser Heinrich VI. (1190) zu Kaiser Ludwig IV. dem Bayern (1347), 1986, Rowohlt, ISBN: 9783498013202

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 8 Das 15. und 16. Jahrhundert. Vom Exil der Päpste in Avignon bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden, 2006, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499616709

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 9 -Mitte des 16. bis Anfang des 18. Jahrhunderts. Vom Völkermord in der Neuen Welt bis zum Beginn der Aufklärung, 2010, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499624438

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums: Bd. 10 18. Jahrhundert und Ausblick auf die Folgezeit. Könige von Gottes Gnaden und Niedergang des Papsttums, 2014, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN: 9783499630200

- Karlheinz Deschner, Hubert Mania, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums 1-10: Sachregister und Personenregister, 2014, Rowohlt, Reinbek, ISBN 978-3-499-63055-2

- Karlheinz Deschner, Abermals krähte der Hahn - Eine kritische Kirchengeschichte von den Evangelisten bis zu den Faschisten, 2015, Alibri Verlag, ISBN: 9783865691880

- Karlheinz Deschner, Horst Herrmann, Der Anti-Katechismus - 200 Gründe gegen die Kirchen und für die Welt, 1993, Goldmann, ISBN: 9783442123438

- Karlheinz Deschner, Der gefälschte Glaube - eine kritische Betrachtung kirchlicher Lehren und ihrer historischen Hintergründe, 2004, Knesebeck, ISBN: 9783896602282

- Karlheinz Deschner, Mit Gott und den Faschisten. Der Vatikan im Bunde mit Mussolini, Franco, Hitler und Pavelić, 2012, Günther, Stuttgart, 1965, Neuauflage: Ahriman, Freiburg im Breisgau 2012, ISBN 978-3-89484-610-7

- Karlheinz Deschner, Das Kreuz mit der Kirche. Eine Sexualgeschichte des Christentums, 1974, Econ, Düsseldorf 1974; überarbeitete Neuausgabe 1992; Sonderausgabe 2009, ISBN 978-3-9811483-9-8

- Karlheinz Deschner, Ein Jahrhundert Heilsgeschichte. Die Politik der Päpste im Zeitalter der Weltkriege, 182/83, 2 Bände, Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Köln, ISBN 978-3-86569-116-3

- Karlheinz Deschner, Die Vertreter Gottes. Eine Geschichte der Päpste im 20. Jahrhundert, 1994, Heyne, München, ISBN 3-453-07048-8

comments