The phenomenon of traveling preachers in 1st-century Judea and Galilee

The role of itinerant preachers in 1st-century Judea and Galilee is an essential aspect of understanding the religious and social dynamics of the period. This broader context sheds light on figures like Jesus, who emerged within a tradition of wandering teachers and prophets. Examining the cultural and historical backdrop of itinerant preaching reveals a landscape marked by socio-political unrest, religious ferment, and apocalyptic expectations, where individuals carrying messages of divine justice, repentance, and hope played significant roles.

The prophet Elijah in his chariot in the whirlwind, fresco, Anagni Cathedral, c. 1250. This scene depicts the prophet Elijah being taken up to heaven in a chariot of fire, as described in 2 Kings 2:11. Elijah is a significant figure in Jewish and Christian tradition, known for his miracles and confrontations with idolatry. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The historical and cultural context of itinerant preaching

In the 1st century CE, Judea and Galilee were regions marked by political instability, Roman occupation, and socio-religious ferment. This environment gave rise to numerous movements and figures, including prophets, healers, and apocalyptic preachers. Itinerant preaching was not unique to Jesus; rather, it was a recognized phenomenon shaped by Jewish traditions and the broader Greco-Roman world.

The Jewish prophetic tradition

Jewish religious culture had long valued the role of prophets and teachers who acted as intermediaries between YHWH and the people. Figures like Elijah, Elisha, and Jeremiah served as models for itinerant ministry, often traveling to deliver divine messages or enact symbolic actions. This prophetic tradition laid the groundwork for later narratives about preachers, including John the Baptist and Jesus, whose story operated within a framework that combined proclamation, moral teaching, and eschatological expectation.

Socio-economic factors

The 1st-century landscape was characterized by stark economic inequality and a disenfranchised peasant class. The Roman Empire’s taxation system, coupled with local aristocratic exploitation, created widespread social unrest. Itinerant preachers often emerged as voices of critique and hope, addressing the grievances of the oppressed and offering visions of divine intervention and justice.

Apocalyptic expectations

The period was also rife with apocalyptic expectations. Many Jews anticipated the imminent arrival of YHWH’s kingdom, a belief rooted in texts like Daniel and [Enoch](/weekend_stories/told/2025/2025-01-11-enochs_influence_on_jesus_narrative/. Traveling preachers often drew upon these themes, proclaiming a coming era of divine rule that would overturn existing social and political hierarchies.

Being a traveling preacher in 1st-century Judea and Galilee

To be a traveling preacher in 1st-century Judea and Galilee was to adopt a lifestyle of mobility, dependence, and public proclamation. These individuals operated outside established religious institutions, relying on personal charisma, the hospitality of local communities, and the power of their message to sustain their ministry.

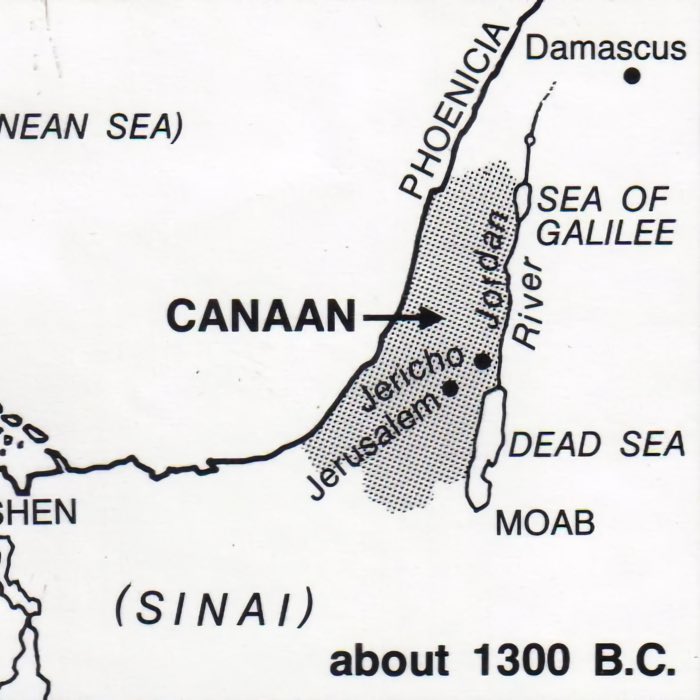

Left: Roman provinces in the 1st century in the Levant. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Satellite map of the Levant and Canaan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Lifestyle and mobility

Traveling preachers often renounced permanent homes and stable livelihoods, embracing itinerancy as a symbolic act of dependence on YHWH. This lifestyle reflected a commitment to their message and distinguished them from local religious authorities, such as priests and Pharisees, who were tied to fixed locations and institutions.

For the figure of Jesus, this lifestyle is evident in his instructions to his disciples: “Take nothing for the journey — no staff, no bag, no bread, no money, no extra shirt” (Luke 9:3). This radical dependence on hospitality underscored the preacher’s role as a messenger of divine truths rather than a self-serving figure.

Modes of proclamation

The primary activity of a traveling preacher was public teaching. This often took place in synagogues, marketplaces, and open fields, where preachers could reach a diverse audience. Their messages typically included calls to repentance, ethical exhortations, and visions of a transformed future. For Jesus, parables became a hallmark of his teaching style, using everyday imagery to convey profound spiritual truths.

In addition to verbal proclamation, traveling preachers often performed symbolic actions — healing the sick, exorcising demons, or staging public demonstrations. These acts reinforced their authority and signified the inbreaking of divine power into the world.

Social role

Traveling preachers often functioned as both critics of the status quo and facilitators of communal renewal. They challenged established authorities, including religious elites and Roman rulers, while fostering communities of followers who shared their vision of YHWH’s kingdom. These preachers were not merely isolated figures but catalysts for social and spiritual movements.

Jesus in the context of other traveling preachers

The figure of Jesus, as portrayed in the Gospels, is one among several itinerant preachers depicted in 1st-century Judea and Galilee. His narrated ministry should be understood alongside other characters from biblical and historical accounts who similarly conveyed messages of repentance, divine justice, and eschatological hope.

John the Baptist

Within the New Testament narrative, John the Baptist is presented as a significant contemporary of Jesus. His role in calling people to repentance and his practice of baptism in the Jordan River serve as a precursor to Jesus’ ministry. The apocalyptic tone of John’s message, emphasizing the imminent judgment of YHWH, reflects the socio-religious expectations of the time. The Gospels depict Jesus as initially associating with John, before diverging in focus by emphasizing themes such as forgiveness and inclusion over judgment.

Other apocalyptic figures

Other figures, such as Theudas and the unnamed “Egyptian prophet” mentioned by Josephus in Antiquities, illustrate the broader phenomenon of apocalyptic preaching. These characters, like those in biblical accounts, gathered followers by proclaiming imminent divine intervention and deliverance. While the narrative surrounding Jesus incorporates similar eschatological themes, it also distinguishes him through an emphasis on inner transformation and non-violence.

The Pharisees and other teachers

The Pharisees, primarily associated with synagogues in the biblical narrative, are also depicted as engaging in forms of itinerant teaching. Their focus on Torah interpretation and moral guidance parallels certain elements of Jesus’ Jesus’ teachings. However, the Gospels highlight tensions between Jesus and the Pharisees, often framing Jesus’ approach as more inclusive and critical of legalistic interpretations of the law.

What did Jesus’ preaching emphasize?

According to the biblical narrative, the core themes of Jesus’ preaching center around the concept of the “Kingdom of God”, repentance, and ethical living. Rooted in Jewish tradition, the portrayal of Jesus in the Gospels emphasizes a message that blends eschatological hope with radical inclusivity and compassion.

Core themes of Jesus’ preaching

“The Kingdom of God” is a central motif in the Gospels’ portrayal of Jesus’ ministry. This multifaceted concept involves divine justice, renewal, and the fulfillment of YHWH’s covenant with humanity. The narrative emphasizes that the Kingdom is both a present reality and a future hope, attainable through personal transformation and communal harmony.

The Kingdom of God

In the Gospel accounts, Jesus frequently conveys that the Kingdom is not a distant event but something accessible through repentance and faith. Passages like Luke 17:21 depict Jesus as declaring, “The Kingdom of God is in your midst”, underscoring an invitation to experience divine grace in the present.

Ethical and social teachings

The ethical dimension of Jesus’ message is exemplified in teachings such as the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5–7). The Beatitudes, in particular, highlight values like humility, mercy, and peacemaking, portraying these qualities as central to the Kingdom. The command to “love your enemies” (Matthew 5:44) and the parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37) challenged conventional boundaries of kinship and moral obligation, redefining neighborly love as universal and unconditional.

Repentance and forgiveness

Repentance is another recurring theme in the Gospels’ depiction of Jesus’ message — a turning away from sin and toward YHWH. Unlike the judgment-centric rhetoric attributed to some other figures, Jesus’ narrative emphasizes forgiveness and reconciliation. Encounters with marginalized individuals, such as the woman caught in adultery (John 8:1–11), serve to illustrate this focus on grace.

The inversion of power structures

The Gospel accounts frequently depict Jesus subverting conventional power dynamics, proclaiming that “the last shall be first” (Matthew 20:16) and that true greatness lies in servanthood (Mark 10:43–45). His parables often contrast the self-righteousness of religious elites with the genuine faith of ordinary people, suggesting an alternative vision of social order.

Eschatological hope

While apocalyptic expectations are a common theme in 1st-century Judean preaching, the Gospels portray Jesus as emphasizing personal and communal renewal over political revolution. This perspective on the Kingdom of God distinguishes his narrative from other apocalyptic figures, focusing on peace and justice rather than violent upheaval.

The methodology of Jesus’ preaching

The Gospels depict Jesus as employing a distinctive approach to preaching, combining relatable storytelling, symbolic acts, and personal engagement to convey his message.

Parables

Parables feature prominently in the Gospel portrayal of Jesus’ teaching method. These short, narratnarrative-driven analogies draw on everyday life to illustrate spiritual truths, inviting listeners to reflect and derive meaning. Stories like the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11–32) and the Sower (Mark 4:1–20) exemplify this technique.

Symbolic actions

Symbolic actions reinforce the narrative’s depiction of Jesus’ authority and message. The cleansing of the Temple (Mark 11:15–17) is presented as a dramatic critique of religious corruption, while healing miracles and exorcisms symbolize the inbreaking of YHWH’s power into the world.

Dialogue and engagement

The Gospel accounts often portray Jesus as engaging in dialogue with diverse audiences, including disciples, skeptics, and adversaries. His responses to questions, whether posed sincerely or as traps, frequently reveal deeper spiritual insights, as exemplified in the exchange about paying taxes to Caesar (Mark 12:13–17).

Inclusivity in outreach

The inclusivity of Jesus’ ministry is a recurring theme in the Gospels. He is depicted as reaching out to marginalized groups, such as tax collectors, Samaritans, and women, challenging prevailing social norms. The encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well (John 4:4–26) illustrates this boundary-crossing approach.

What set Jesus apart?

In the biblical narrative, several aspects of Jesus’ ministry are presented as distinctive:

Authority and authenticity

The Gospels describe Jesus as teaching with an authority that astonished his listeners (Mark 1:22). Unlike the scribes and Pharisees, who relied on established traditions, Jesus is portrayed as asserting direct access to divine truth.

Radical inclusivity

The inclusivity of Jesus’ ministry, as depicted in the Gospels, challenges prevailing religious norms. His association with sinners and outcasts is presented as a defining feature of his message

Integration of word and deed

In the narrative, Jesus’ actions consistently reinforce his teachings. His miracles and acts of compassion are portrayed not merely as displays of power but as embodiments of his message of restoration and hope.

The centrality of love

The Gospels emphasize love — for YHWH, neighbor, and even enemies — as the fulfillment of divine law (Matthew 22:37–40). This theme is presented as a cornerstone of Jesus’ ethical teaching.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of itinerant preaching in 1st-century Judea and Galilee reflects a dynamic interplay of religious tradition, socio-political factors, and personal charisma, contributing to long-term developments in religious movements and practices. This tradition influenced later religious expressions and set a precedent for future spiritual leaders operating outside established institutions. These preachers, within the narrative framework, including figures like John the Baptist and Jesus, emerged as voices of hope and critique in a tumultuous era. The legacy of these figures lies not only in their immediate impact but also in their influence on subsequent religious thought and practice.

References and further reading

- Fredriksen, P., Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews: A Jewish Life and the Emergence of Christianity, 2000, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, ISBN: 978-0679767466

- Crossan, J. D., The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant, 1993, HarperOne, ISBN: 978-0060616298

- Vermes, G., Jesus the Jew: A Historian’s Reading of the Gospels, 2011, SCM Press, ISBN: 978-0334028390

- Sanders, E. P., The Historical Figure of Jesus, 1996, Penguin Books, ISBN: 978-0140144994

- Richard Carrier, On the historicity of Jesus – Why we might have reason for doubt, 2014, Sheffield Phoenix Press, ISBN: 9781909697492

- Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist?, 2013, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780062206442

comments