The rise of Rabbinic Judaism: Jewish philosophy after the Temple’s destruction

The destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE by the Romans marked a profound turning point in the history of Judaism. The event not only brought an end to the central institution of Jewish religious life but also precipitated a period of theological, philosophical, and cultural transformation. In the aftermath, Rabbinic Judaism emerged as the dominant expression of Jewish religious thought and practice, redefining the foundations of Jewish identity and worship.

Siege and Destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans, David Roberts, 1850. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical context: The crisis of 70 CE

The destruction of the Second Temple by Roman forces during the First Jewish-Roman War (66–73 CE) shattered the institutional and theological core of Second Temple Judaism. For centuries, the Temple had served as the focal point of Jewish worship, ritual practice, and communal identity. The sacrificial system, central to the covenantal relationship between God and Israel, was rendered obsolete. Moreover, the political and social upheaval that followed the war exacerbated the sense of dislocation among the Jewish people.

Herod’s Temple as imagined in the Holyland Model of Jerusalem. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Amid this crisis, the rabbis — scholars and teachers who would become the intellectual and spiritual leaders of post-Temple Judaism — developed a new religious framework. This framework preserved the essence of Jewish theology while adapting to the realities of a world without a Temple.

Philosophical innovations of Rabbinic Judaism

The rise of Rabbinic Judaism involved significant philosophical shifts, as the rabbis reinterpreted foundational Jewish concepts and practices to address the challenges of their time. Central to this transformation was the emphasis on Torah, the reinterpretation of divine presence, and the redefinition of sacred space.

The centrality of Torah study

The rabbis elevated Torah study to the heart of Jewish religious life, replacing the sacrificial system with the intellectual and spiritual discipline of engaging with sacred texts. The Torah was no longer seen solely as a legal and ritual code but as a comprehensive guide to all aspects of life. Rabbinic Judaism emphasized the oral tradition (Torah Shebe’al Peh), which the rabbis believed complemented the written Torah (Torah Shebichtav).

This shift reflected a democratization of Jewish religious life. Without the Temple or a centralized priesthood, religious authority became rooted in the study and interpretation of scripture, an activity that could be undertaken by any Jew willing to devote themselves to learning. This transformation positioned the rabbis as the custodians of Jewish tradition and ensured the continuity of Jewish thought in the diaspora.

God’s presence beyond the Temple

The rabbis redefined the concept of the divine presence (Shekhinah), emphasizing its accessibility beyond the confines of the Temple. Rabbinic teachings assert that the Shekhinah dwells wherever Jews engage in Torah study or gather in prayer. This innovation not only addressed the loss of the Temple but also reimagined Jewish worship as a portable and decentralized practice.

Texts such as Pirkei Avot emphasize the sanctity of communal spaces where Torah is studied, declaring, “When two sit together and exchange words of Torah, the Shekhinah dwells among them.” This shift underscored the adaptability of Jewish theology, enabling it to thrive in diverse geographic and cultural contexts.

Redefining sacred space and time

In the absence of the Temple, the rabbis reoriented Jewish religious life around sacred time rather than sacred space. The observance of Shabbat, festivals, and daily prayers became the primary means of maintaining the covenantal relationship with God. Rabbinic Judaism imbued these practices with rich theological significance, ensuring that Jewish identity remained rooted in collective memory and communal worship.

Rabbinic literature: Codifying the new framework

The philosophical and theological innovations of Rabbinic Judaism were codified in a vast body of literature, including the Mishnah, Talmud, and Midrash. These texts served as the foundation for rabbinic thought, offering legal, ethical, and theological guidance.

The Mishnah

Compiled around 200 CE by Rabbi Judah the Prince, the Mishnah represents the first major codification of the oral tradition. Organized thematically, it provides a comprehensive framework for Jewish law (halakhah), addressing issues ranging from ritual purity to ethical behavior. The Mishnah’s emphasis on legal reasoning reflects the rabbinic commitment to integrating religious principles into all aspects of life.

The Talmud

The Talmud, comprising the Babylonian and Jerusalem editions, expands upon the Mishnah through extensive commentary and discussion. Its dialectical method reflects the rabbis’ philosophical approach, emphasizing debate, interpretation, and the pursuit of truth. The Talmud’s exploration of ethical and metaphysical questions underscores the philosophical depth of Rabbinic Judaism.

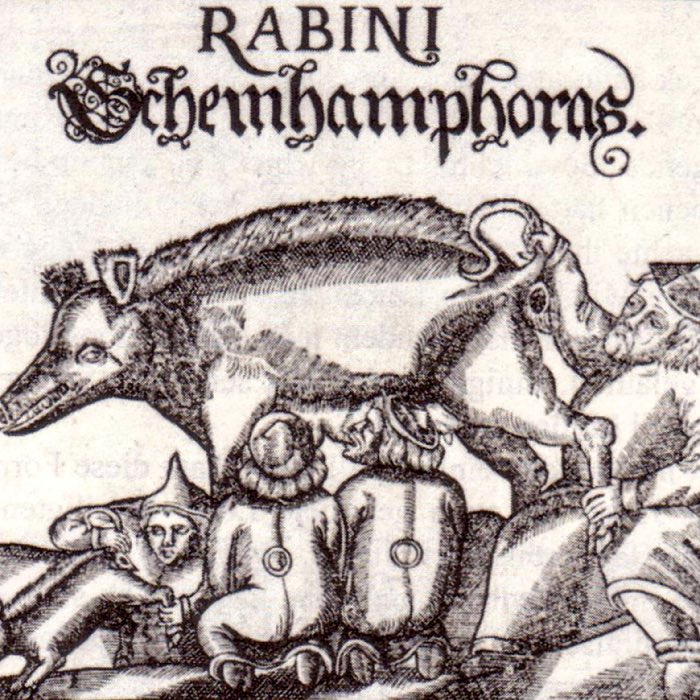

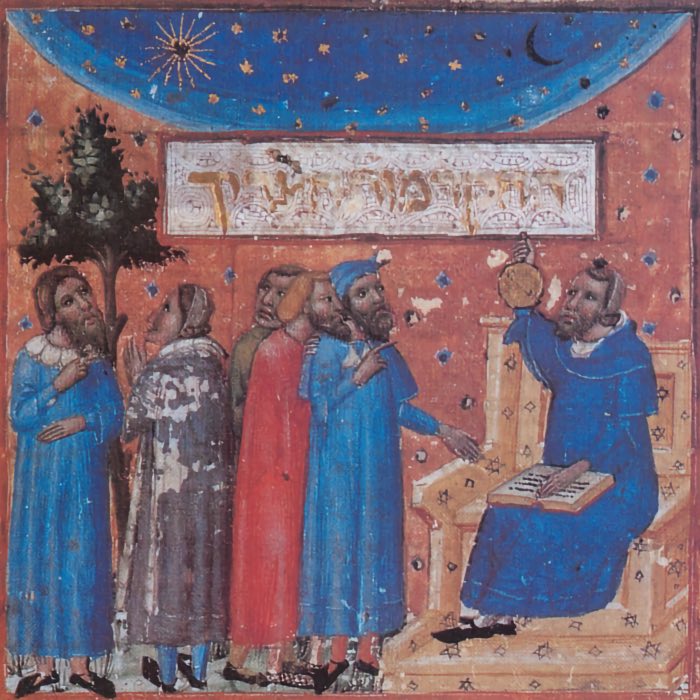

Woodcut carved by Johann von Armssheim (1483). Portrays a disputation between Christian and Jewish scholars. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Midrash

Midrashic literature, which includes both legal (halakhic) and narrative (aggadic) interpretations of scripture, demonstrates the rabbis’ creative engagement with the biblical text. Through allegory, parable, and exegetical analysis, the rabbis infused ancient texts with new meaning, addressing contemporary concerns while preserving the integrity of the tradition.

Rabbinic ethics and philosophy

Rabbinic Judaism’s emphasis on law and interpretation was complemented by a rich ethical philosophy. The rabbis articulated a vision of human responsibility that integrated individual virtue, communal solidarity, and the pursuit of justice.

The concept of Middot (virtues)

Rabbinic teachings emphasize the cultivation of virtues, or middot, as essential to ethical living. Traits such as humility, patience, and generosity are presented as reflections of divine attributes, embodying the principle of imitatio Dei (imitation of God). Texts such as Pirkei Avot offer practical guidance for developing these virtues, reinforcing the connection between ethical conduct and spiritual growth.

Tikkun Olam (repairing the world)

The concept of tikkun olam, often translated as “repairing the world”, encapsulates the rabbinic commitment to social justice and communal responsibility. While initially associated with legal measures to maintain social order, tikkun olam evolved into a broader ethical principle, emphasizing the role of human agency in realizing divine ideals.

Theodicy and human agency

In the aftermath of the Temple’s destruction, the rabbis grappled with questions of suffering, divine justice, and human responsibility. Rabbinic teachings often emphasize the redemptive potential of human actions, portraying ethical behavior as a means of mitigating suffering and bringing about divine favor.

Conclusion

The rise of Rabbinic Judaism after the destruction of the Second Temple represents one of the most significant transformations in Jewish history. By reimagining Jewish identity, worship, and communal practice in a post-Temple era, the rabbis created a dynamic and adaptable framework that ensured the survival and flourishing of Jewish religious and intellectual life across centuries and continents.

Through its emphasis on Torah study, ethical conduct, and communal engagement, Rabbinic Judaism not only preserved Jewish traditions but also contributed to the shared intellectual heritage of the Abrahamic faiths. Its philosophical innovations, particularly in the areas of scripture interpretation and legal thought, influenced emerging Christian and Islamic theologies. The legacy of Rabbinic Judaism lies in its ability to respond to historical upheaval with theological and social creativity, ensuring that Jewish life remained alive and relevant.

References and further reading

- Alexander Brungs, Georgi Kapriev, Vilem Mudroch, Die Philosophie des Mittelalters. Bd. 1. Byzanz. Judentum, 2019, Schwabe Verlagsgruppe, ISBN: 9783796526237

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Richard Friedman, Who Wrote The Bible?, 2019, Simon & Schuster, ISBN: 9781501192401

- James Karl Hoffmeier, Akhenaten And The Origins Of Monotheism, 2015, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780199792085

- Jan Assmann, From Akhenaten to Moses - Ancient Egypt and religious change, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9789774166310

- Benjamin D. Sommer, The Bodies Of God And The World Of Ancient Israel, 2009, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521518727

- William G. Dever, Did God have a wife? - Archaeology and folk religion in ancient Israel, 2008, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802863942

- James S. Anderson, Monotheism and Yahweh’s appropriation of Baal, 2015, Bloomsbury T&T Clark, eThe Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies, ISBN: 978-0567683076

- Stephen Mitchell, Peter Van Nuffelen, One God – Pagan monotheism In the Roman Empire, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521194167

- William G. Dever, Who were the early Israelites and where did they come from?, 2006, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802844163

- William M. Schniedewind, How the Bible became a book – The textualization of ancient Israel, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521829465

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bart D. Ehrman, Forged: Writing in the name of God – Why the Bible’s authors are not who we think they are, 2011, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780062012616

- Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus – Apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium, 1999, Oxford University Press on Demand, ISBN: 9780195124736

- Bart D. Ehrman, God’s problem: How the Bible fails to answer our most important question – Why we suffer, 2008, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780061578311

- Israel Knohl, The Messiah Before Jesus - The Suffering Servant Of The Dead Sea Scrolls, 2000, Univ of California Press, ISBN: 9780520215924

- Smith, M. S., The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel, 2002, Eerdmans, ISBN: 978-0802839725

- Coogan, M. D., The Oxford History of the Biblical World, 2001, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192802033

- Miller, P. D., The Religion of Ancient Israel, 2007, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN: 978-0664232375

comments