Zoroastrian influence on Judaism

The interaction between Zoroastrianism and Judaism is a subject of considerable scholarly interest, particularly because both religious traditions share striking similarities in their cosmology, eschatology, and ethical dualism. Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest known monotheistic religions, developed in ancient Persia around the 6th century BCE, a period that coincides with significant historical events in Jewish history, such as the Babylonian exile and subsequent Persian rule. This temporal and geographical proximity provides a plausible framework for cultural and religious exchange.

The so-called rings of the Fravashi decorated tiles. The Fravashi are guardian spirits in Zoroastrianism.

Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical context of interaction

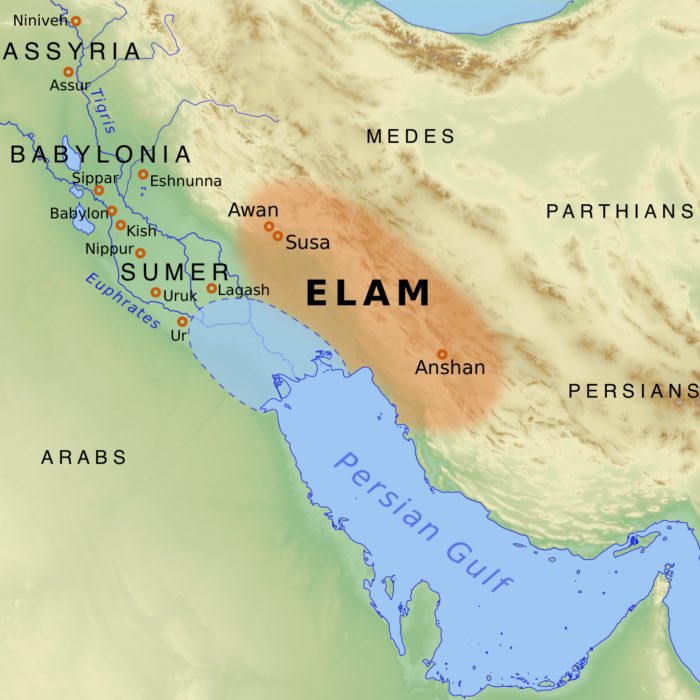

The most significant point of contact between Judaism and Zoroastrianism occurred during and after the Babylonian exile (586–538 BCE). Following the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid Empire and a Zoroastrian, the Jewish exiles were allowed to return to their homeland and rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem. Cyrus is even referred to as a messianic figure in the Hebrew Bible (Isaiah 45:1), reflecting the gratitude and reverence with which the Jewish people regarded him.

During the Persian period (538 BCE–332 BCE), Jewish communities lived under Persian rule, and there was ample opportunity for the exchange of religious and philosophical ideas. The Zoroastrian worldview, with its emphasis on cosmic dualism, ethical responsibility, and eschatological judgment, may have influenced evolving Jewish theological concepts during this period.

Key areas of Zoroastrian influence on Judaism

Cosmology and dualism

One of the most striking parallels between Zoroastrianism and post-exilic Judaism is the concept of cosmic dualism. In Zoroastrianism, the world is seen as a battleground between two opposing forces: Ahura Mazda, the god of light and wisdom, and Angra Mainyu (Ahriman), the spirit of darkness and chaos. Although Judaism remains strictly monotheistic, the post-exilic texts reflect an increasing emphasis on the opposition between good and evil, light and darkness.

For instance, the Dead Sea Scrolls, particularly the War Scroll and the Community Rule, describe a cosmic battle between the forces of light and darkness, a theme reminiscent of Zoroastrian dualism. Moreover, the figure of Satan in the Hebrew Bible evolves from being merely an accuser in early texts (e.g., the Book of Job) to a more adversarial figure in later Jewish literature, potentially reflecting Zoroastrian influence.

Angelology and demonology

Zoroastrianism possesses a well-developed system of angelology and demonology, with divine beings (Amesha Spentas) serving Ahura Mazda and demonic forces aiding Angra Mainyu. In later Jewish texts, particularly in apocalyptic literature such as the Book of Daniel and the Book of Enoch, we observe a more elaborate hierarchy of angels and demons. This development is not as prominent in pre-exilic Jewish texts, suggesting a possible influence from Zoroastrian religious ideas.

The idea of archangels with specific roles, such as Michael and Gabriel, bears similarity to the Zoroastrian concept of Yazatas, divine entities who serve different functions in the cosmic order. The demonization of certain figures in Jewish texts, such as Azazel, may also reflect parallels with Zoroastrian demonology.

Eschatology and resurrection

Zoroastrianism is known for its detailed eschatological vision, including the resurrection of the dead, a final judgment, and the ultimate triumph of good over evil. The idea of bodily resurrection and a final judgment becomes more prominent in Judaism during the Second Temple period. Prior to this period, the Hebrew Bible presents a more ambiguous view of the afterlife, often referring to Sheol, a shadowy existence after death.

The Book of Daniel, one of the latest books of the Hebrew Bible, explicitly mentions the resurrection of the dead and a final judgment (Daniel 12:2). This eschatological framework, which later became central to both Rabbinic Judaism and Christianity, bears a resemblance to Zoroastrian eschatology. Additionally, the notion of a messianic figure who will bring about the final redemption aligns with the Zoroastrian concept of the Saoshyant, a savior who will lead humanity in the final battle against evil.

Ethical dualism and free will

Zoroastrian ethics emphasize the constant choice between good and evil, truth (asha) and falsehood (druj), with significant moral responsibility placed on individuals. This dualistic ethical framework may have influenced Jewish thought during the Persian period, as reflected in the increasing emphasis on moral responsibility and individual accountability in post-exilic Jewish texts.

The emphasis on free will in Zoroastrianism — the idea that humans must choose between the forces of good and evil — finds a parallel in Jewish wisdom literature and later Rabbinic teachings. The moral dichotomy presented in the Book of Proverbs and the ethical exhortations of the prophets resonate with Zoroastrian ethical dualism.

Scholarly perspectives and debates

Scholars remain divided on the extent of Zoroastrian influence on Judaism. While some argue for significant direct borrowing of ideas, others caution against overestimating the impact, emphasizing that many of these developments in Jewish thought could have arisen independently. However, the temporal and geographical context of Jewish-Persian interaction makes a strong case for at least some level of influence.

Mary Boyce, a prominent scholar of Zoroastrianism, has argued that the ethical and eschatological parallels between the two religions are too substantial to be coincidental. On the other hand, Lester Grabbe contends that while there may have been some influence, the distinctiveness of Jewish monotheism and its unique covenantal theology should not be overlooked.

Conclusion

The influence of Zoroastrianism on Judaism is a compelling example of how religious traditions evolve through interaction and exchange. While Judaism retained its fundamental monotheistic framework, the Persian period appears to have introduced new theological ideas that enriched Jewish cosmology, eschatology, and ethics. These developments not only shaped the trajectory of Judaism but also had a lasting impact on Christianity and Islam, both of which inherited many of these concepts from Jewish tradition.

References and further reading

- Boyce, M., Zoroastrians: their religious beliefs and practices, 1979, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415239035

- Grabbe, Lester L., Judaism from Cyrus to Hadrian, 2012, SCM PRESS, ISBN: 978-0334025788

- Alexander Brungs, Georgi Kapriev, Vilem Mudroch, Die Philosophie des Mittelalters. Bd. 1. Byzanz. Judentum, 2019, Schwabe Verlagsgruppe, ISBN: 9783796526237

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Richard Friedman, Who Wrote The Bible?, 2019, Simon & Schuster, ISBN: 9781501192401

- James Karl Hoffmeier, Akhenaten And The Origins Of Monotheism, 2015, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780199792085

- Jan Assmann, From Akhenaten to Moses - Ancient Egypt and religious change, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9789774166310

- Benjamin D. Sommer, The Bodies Of God And The World Of Ancient Israel, 2009, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521518727

- William G. Dever, Did God have a wife? - Archaeology and folk religion in ancient Israel, 2008, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802863942

- James S. Anderson, Monotheism and Yahweh’s appropriation of Baal, 2015, Bloomsbury T&T Clark, eThe Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies, ISBN: 978-0567683076

- Stephen Mitchell, Peter Van Nuffelen, One God – Pagan monotheism In the Roman Empire, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521194167

- William G. Dever, Who were the early Israelites and where did they come from?, 2006, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802844163

- William M. Schniedewind, How the Bible became a book – The textualization of ancient Israel, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521829465

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bart D. Ehrman, Forged: Writing in the name of God – Why the Bible’s authors are not who we think they are, 2011, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780062012616

- Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus – Apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium, 1999, Oxford University Press on Demand, ISBN: 9780195124736

- Bart D. Ehrman, God’s problem: How the Bible fails to answer our most important question – Why we suffer, 2008, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780061578311

- Israel Knohl, The Messiah Before Jesus - The Suffering Servant Of The Dead Sea Scrolls, 2000, Univ of California Press, ISBN: 9780520215924

- Smith, M. S., The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel, 2002, Eerdmans, ISBN: 978-0802839725

- Coogan, M. D., The Oxford History of the Biblical World, 2001, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192802033

- Miller, P. D., The Religion of Ancient Israel, 2007, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN: 978-0664232375

- Smith, Mark S., The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel’s Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts, 2003, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195167689

comments