The role of synagogues in the diaspora

The expansion of the Jewish diaspora during the Hellenistic and Roman periods profoundly shaped the nature and influence of Judaism within the Mediterranean world. As Jewish communities established themselves in the Greek-speaking metropolises of the Roman Empire, synagogues emerged as central institutions for religious, social, and cultural life. These spaces facilitated the practice of Judaism in a diasporic context, enabled the transmission of Jewish teachings in the lingua franca of Greek, and became venues of interaction between Jews and non-Jews. The unique role of synagogues as both sacred and communal spaces contributed to the gradual popularization of Judaism in the Roman world, while also highlighting tensions between inclusivity and exclusivity in Jewish religious practice.

Archaeological remains of a first-century synagogue at Herodium. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Historical context: The Jewish diaspora in the Roman Empire

By the time of Roman ascendancy in the Mediterranean world, Jewish communities were firmly established across the empire, particularly in major urban centers such as Alexandria, Antioch, Rome, and Corinth. This widespread diaspora was facilitated by earlier exilic movements, trade networks, and the Hellenistic expansion following the conquests of Alexander the Great.

Map showing the location of other synagogues in the Jewish Diaspora during the first two centuries CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The integration of Jewish communities into the Roman world was marked by both continuity and adaptation. While maintaining their distinct religious identity, diaspora Jews engaged with Greco-Roman culture, adopting the Greek language, participating in economic and civic life, and navigating the legal structures of the Roman state. This dual identity is evident in the establishment of synagogues, which served as both sacred spaces for Jewish worship and hubs of communal life.

Archaeological remains of a first-century synagogue at Masada. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Synagogues in the diaspora: Sacred and communal spaces

Synagogues in the Roman metropolises were multifunctional institutions that played a central role in preserving Jewish identity and facilitating religious practice in a diasporic context. These structures were not merely places of prayer but also spaces for education, legal proceedings, and social interaction.

Worship and the reading of scripture

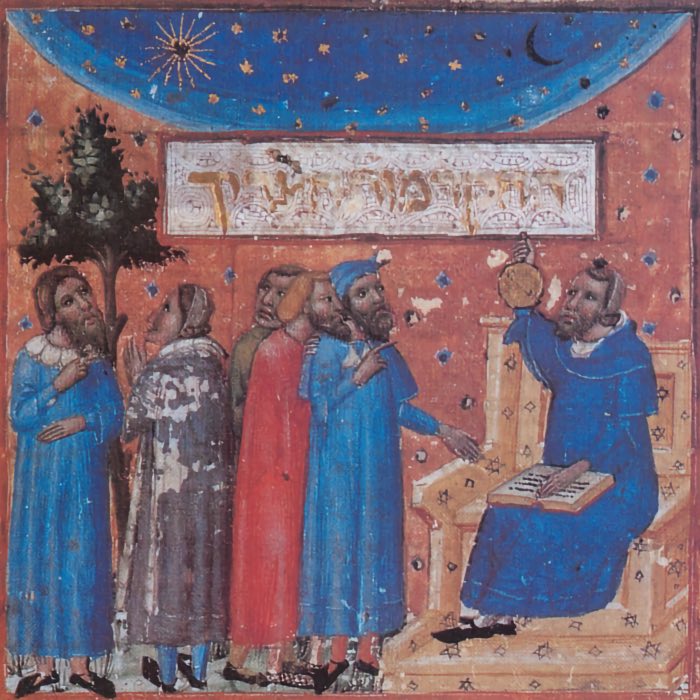

The primary function of synagogues was to facilitate communal worship and the reading of the Torah and other sacred texts. In the diaspora, these readings were often conducted in Greek, reflecting the linguistic reality of Jewish communities living outside Judea. The translation of Hebrew scriptures into Greek, exemplified by the Septuagint, allowed Jews to engage with their sacred heritage while also making these texts accessible to Greek-speaking non-Jews.

Archaeological remains of a mosaic in the Tzippori Synagogue, built in the first half of the 5th century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The weekly reading and interpretation of scripture provided a means of reinforcing religious identity and transmitting Jewish teachings across generations. It also emphasized the centrality of the Torah as a unifying force within diverse Jewish communities.

Education and social cohesion

Synagogues served as centers of education, where children and adults could study Jewish law, ethics, and history. This educational role was essential for maintaining religious knowledge and continuity within the diaspora. Additionally, synagogues functioned as spaces for community gatherings, fostering social cohesion and mutual support among members of the Jewish community.

Architectural and artistic features

The architecture and decoration of synagogues reflected both Jewish traditions and the influence of local cultures. Synagogues in the Roman Empire often incorporated Greco-Roman architectural styles, such as colonnades and mosaics, while also including distinctly Jewish symbols, such as the menorah, the ark of the Torah, and inscriptions in Hebrew or Greek. These features illustrate the dynamic interplay between cultural integration and religious distinctiveness.

Archaeological remains of the synagogue of Kfar Bar’am, built ca. 220 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Synagogues as sites of interaction between Jews and non-Jews

The presence of synagogues in major urban centers made Judaism visible and accessible to non-Jews, many of whom were drawn to its ethical teachings, monotheistic theology, and communal practices. This phenomenon contributed to the gradual popularization of Judaism within the Roman world, particularly among individuals dissatisfied with traditional Greco-Roman polytheism.

The Old Synagogue in Erfurt, Germany, is the oldest intact synagogue building in Europe, in parts around 1100 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The appeal of Judaism to non-Jews

Judaism’s ethical monotheism, as articulated in the teachings of the Torah and the Prophets, appealed to many Greco-Roman individuals seeking a more personal and morally grounded religious framework. The emphasis on justice, compassion, and the worship of a single, transcendent God stood in contrast to the ritualistic and transactional nature of traditional pagan religions.

Non-Jews who were attracted to Judaism often attended synagogue gatherings, where they could hear the reading of scripture and learn about Jewish teachings. Some became “God-fearers” (theosebeis), individuals who admired and partially adhered to Jewish practices without undergoing full conversion. These God-fearers played a significant role in the dissemination of Jewish ideas and the formation of early Christian communities.

Barriers to full inclusion

While synagogues facilitated interaction between Jews and non-Jews, Judaism remained fundamentally an ethnoreligious tradition, closely tied to the covenant between God and the descendants of Abraham. Full conversion to Judaism required adherence to the Mosaic law, including circumcision, dietary restrictions, and ritual observances. These requirements posed significant barriers to non-Jews, particularly in the context of Greco-Roman society, where such practices were often viewed with suspicion or hostility.

The transition to Christianity: Resolving the tensions of inclusivity

The inclusivity of synagogue life and the barriers to full conversion created a dynamic that would profoundly influence the development of early Christianity. The Apostolic Covenant, as articulated in the Acts of the Apostles and the Pauline epistles, addressed these tensions by offering a new framework for religious identity and inclusion.

Paul’s mission to the gentiles

The self-proclaimed “apostle” Paul, himself a product of the Jewish diaspora and its Hellenistic environment, emphasized the universality of the Christian message. Drawing on Jewish wisdom and ethical teachings, Paul argued that faith in Christ transcended ethnic and cultural boundaries, eliminating the need for converts to adhere to the full corpus of Mosaic law. This approach made Christianity accessible to non-Jews while maintaining its roots in Jewish theological traditions.

The role of synagogues in the spread of Christianity

Synagogues served as important venues for the early spread of Christianity, providing a ready audience of Jews and God-fearers who were already familiar with the teachings of the Hebrew scriptures. Paul and other early Christian missionaries often began their outreach in synagogues, using scripture to articulate their message about the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus.

Conclusion

The role of ancient synagogues in the Roman metropolises highlights the dynamic interplay between Jewish religious life, diaspora identity, and cultural integration. As centers of worship, education, and community, synagogues preserved Jewish traditions while also facilitating interaction with the broader Greco-Roman world. This interaction not only contributed to the popularization of Judaism but also set the stage for the emergence of Christianity, which built upon the ethical and theological foundations of Jewish wisdom while addressing the barriers to inclusivity. Without the vibrant and multifaceted life of the ancient synagogues, the spread and transformation of both Judaism and Christianity would have taken a markedly different course.

References and further reading

- Rajak, T., The Jewish Dialogue with Greece and Rome: Studies in Cultural and Social Interaction, 2000, Brill, ISBN: 978-9004112858

- Levine, L. I., The Ancient Synagogue: The First Thousand Years, 2005, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300106282

- Feldman, L. H., Jew and Gentile in the Ancient World: Attitudes and Interactions from Alexander to Justinian, 1996, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691029276

- Goodman, M., Mission and Conversion: Proselytizing in the Religious History of the Roman Empire, 1996, Clarendon Press, ISBN: 978-0198263876

comments