The evolution of Judaic philosophy and thought: A matter of constant development

Throughout its long history, Judaism has demonstrated an extraordinary capacity for adaptation and renewal, shaped by both internal evolution and external pressures. Far from being an isolated or static tradition, Judaism has continuously interacted with surrounding cultures, absorbing, reinterpreting, and, at times, resisting external influences. These interactions have played a significant role in the development of Jewish theology, religious practice, and communal identity. This article explores the dynamic relationship between Judaism and the cultures it encountered, highlighting how these exchanges have contributed to the rich diversity of Jewish thought and life.

Kennicott Bible, a 1476 Spanish Tanakh. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical foundations of external interaction

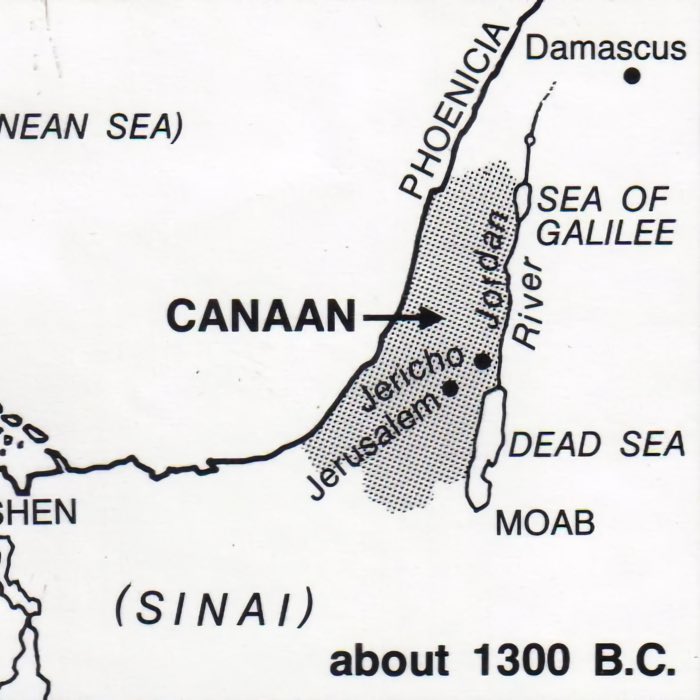

Judaism emerged in the ancient Near East, a region characterized by a complex interplay of civilizations and religious traditions. The early Israelites shared their cultural milieu with Canaanites, Mesopotamians, and Egyptians, whose religious concepts and practices undoubtedly influenced early Israelite religion. As the Israelites transitioned from a loose confederation of tribes to a centralized kingdom, they encountered new cultural and religious ideas, which played a role in shaping their developing monotheism.

The Babylonian exile (586 BCE) marked a pivotal moment in Jewish history. Removed from their homeland and temple, the exiled Jewish population faced the challenge of maintaining their religious identity in a foreign land. The exile prompted significant theological reflection, leading to the development of ideas such as the universal sovereignty of God and the emphasis on the study of sacred texts. This period also set the stage for subsequent interactions with the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman empires, each of which left a lasting imprint on Judaism.

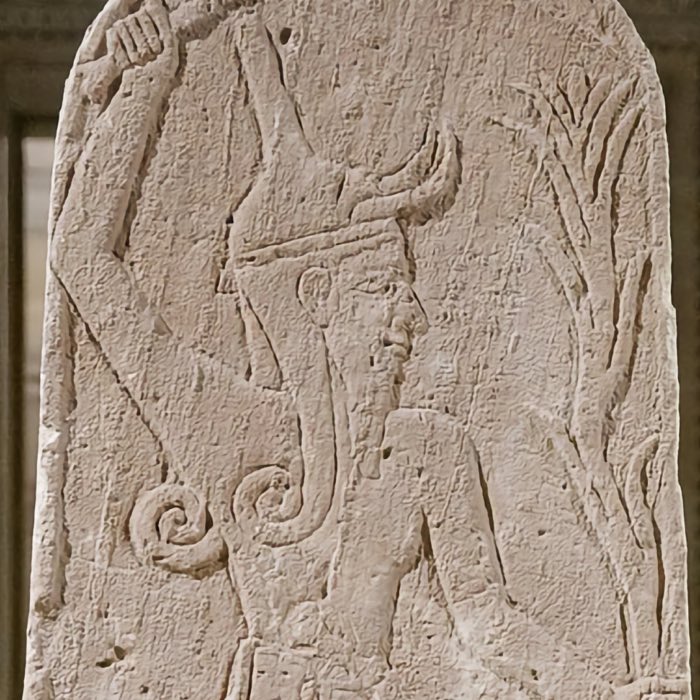

Canaanite influence: Early religious foundations

Before the emergence of Judaism as a distinct monotheistic religion, the early Israelites shared a cultural and religious environment with the Canaanites, the indigenous people of the Levant. Archaeological and textual evidence suggests that early Israelite religion bore significant similarities to Canaanite religious practices. For example, the worship of Yahweh in early Israel likely developed alongside or in response to the Canaanite pantheon, which included prominent deities such as El, Baal, and Asherah.

In particular, the Canaanite god El, often depicted as the chief deity of their pantheon, may have influenced the early conception of Yahweh. In some biblical texts, Yahweh is referred to with titles traditionally associated with El, such as El Shaddai (God Almighty) and Elyon (Most High). The eventual transition from a polytheistic framework to monotheism in Israelite religion can be seen as a process of differentiation from Canaanite traditions while retaining certain elements.

Another notable parallel is the use of sacred high places (bamot) and altars, which were common in both Canaanite and early Israelite worship. The biblical narrative reflects this shared practice while also emphasizing the centralization of worship in Jerusalem as a distinctive development of later Judaism. Additionally, the Canaanite influence is evident in the rich use of agricultural and fertility imagery in early biblical texts, reflecting the agrarian context of the region.

Persian influence: The emergence of eschatology and angelology

The Persian period, following Cyrus the Great’s conquest of Babylon, introduced Jewish communities to Zoroastrianism, a religion with a dualistic worldview, a detailed eschatology, and a hierarchical system of divine beings. While Judaism retained its strict monotheism, it began to incorporate elements reminiscent of Zoroastrian thought, such as the concept of a final judgment, resurrection of the dead, and a more developed angelology. These ideas became prominent in Jewish apocalyptic literature and later influenced both Christianity and Islam.

Hellenistic influence: Philosophical thought and scriptural interpretation

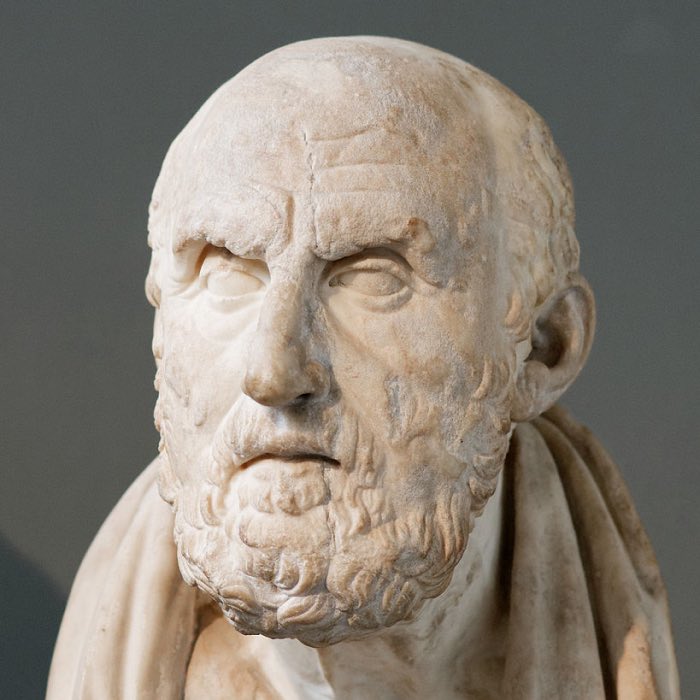

The conquest of the Near East by Alexander the Great ushered in a new era of Hellenistic cultural dominance. Jewish communities, particularly those in Alexandria, encountered Greek philosophy and modes of thought, leading to a period of significant intellectual cross-pollination. The translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek (the Septuagint) not only made Jewish scripture accessible to the wider Hellenistic world but also facilitated new interpretations influenced by Greek philosophical concepts.

Map of the empire of Alexander the Great. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Map of the empire of Alexander the Great. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Philo of Alexandria, a prominent Jewish philosopher of the early first century CE, exemplifies this synthesis of Jewish theology and Hellenistic philosophy. Drawing on Platonic and Stoic ideas, Philo developed an allegorical method of scriptural interpretation, seeking to harmonize Jewish religious teachings with Greek philosophical principles. While Philo’s ideas did not gain widespread acceptance within mainstream Judaism, they played a crucial role in shaping early Christian thought.

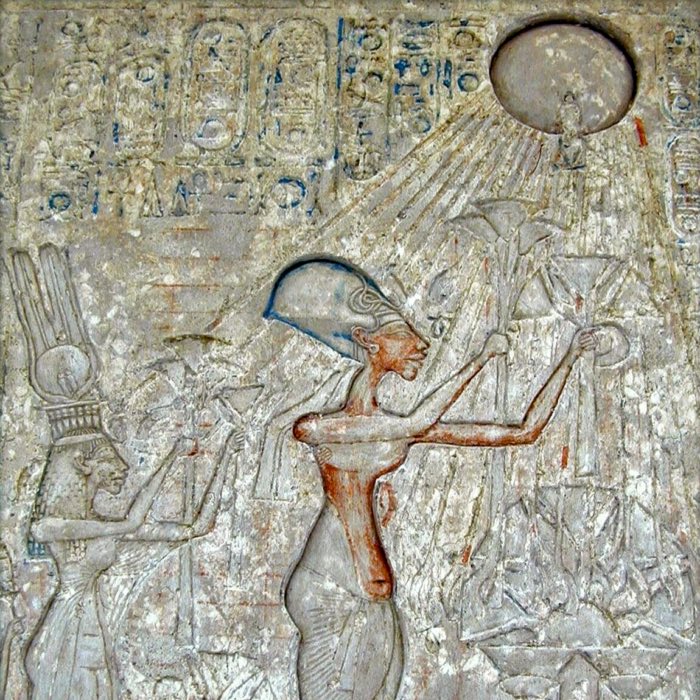

Egyptian influence: Symbols and cosmology

Egypt, with its ancient religious traditions and powerful cultural heritage, exerted a lasting influence on the Israelite religion. The Israelites’ early contact with Egypt is reflected in the biblical narrative of the Exodus, a foundational story of liberation and covenant. Later, during periods of Egyptian political dominance over Canaan and ongoing trade relations, Jewish communities encountered Egyptian religious symbols and cosmological ideas.

While Judaism ultimately rejected the polytheism of Egypt, certain motifs, such as the use of light and darkness in cosmological narratives and the emphasis on ritual purity, bear traces of Egyptian influence. The development of Jewish priestly traditions, as outlined in the Torah, shows parallels with Egyptian temple practices, adapted to fit the monotheistic framework of Judaism.

Roman influence: Diaspora and communal identity

The Roman period saw the dispersion of Jewish communities throughout the Mediterranean world, leading to the development of a vibrant Jewish diaspora. Interaction with Roman society and other religious communities within the empire prompted new challenges and adaptations. Synagogues became central institutions for Jewish religious life, replacing the temple as focal points of worship, study, and community.

Judaism’s encounter with Roman religious pluralism and philosophical schools further stimulated internal debates about law, identity, and theology. Rabbinic Judaism, which emerged in the aftermath of the Temple’s destruction in 70 CE, reflects the synthesis of these diverse influences. The rabbis preserved Jewish distinctiveness while engaging with the surrounding intellectual and cultural environment, ensuring the continuity of Jewish tradition in a rapidly changing world.

Summary table of Jewish belief concepts and external influences

| Jewish belief/concept | Potential origin/influence | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Monotheism | Canaanite religion (El), Egyptian Atenism | Developed from early monolatry, influenced by Canaanite chief deity El. |

| Yahweh (YHWH) | Canaanite religion (El), Egyptian and Mesopotamian deities | Early Israelite worship of Yahweh likely developed alongside Canaanite deities such as El and Baal. Over time, Yahweh became central to Israelite monotheism, transforming from a local war deity into the universal God of Israel. |

| Angelology and Demonology | Zoroastrianism | The hierarchy of angels and dualistic struggle between good and evil. |

| Resurrection and Final Judgment | Zoroastrian eschatology | Concept of bodily resurrection and moral accountability after death. |

| Creation from Chaos | Egyptian and Mesopotamian cosmology | The motif of primordial waters and divine ordering of chaos. |

| Ethical dualism | Zoroastrianism | Emphasis on moral choices between good (truth) and evil (falsehood). |

| Ritual purity and priesthood | Egyptian temple practices | Similar purity laws and priestly functions adapted to a monotheistic context. |

| Sacred high places and altars | Canaanite religious practices | Use of bamot (high places) for early worship before centralization in Jerusalem. |

| Wisdom literature | Hellenistic philosophy (Stoicism, Platonism) | Development of Jewish philosophical thought, exemplified by Philo. |

| Diaspora identity | Roman influence | Synagogues as communal centers and adaptation to pluralistic societies. |

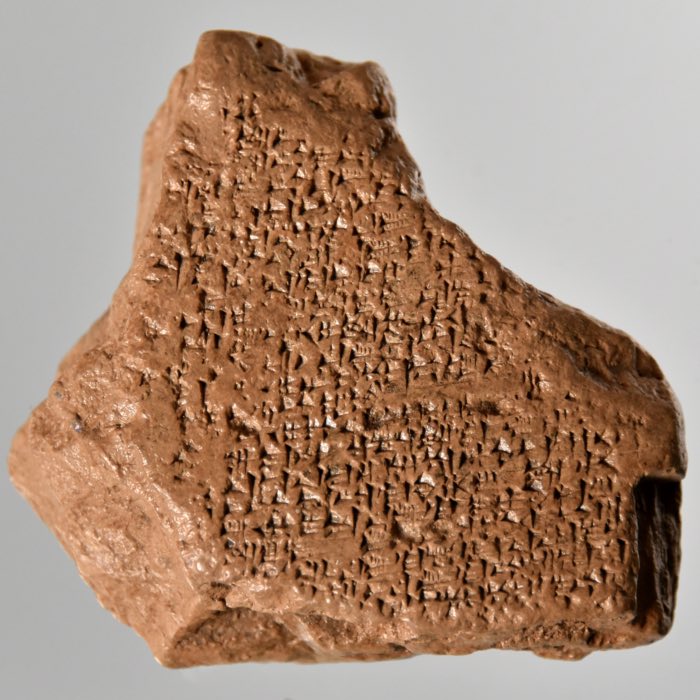

| Flood narrative | Mesopotamian | The biblical story of Noah shares similarities with the Mesopotamian flood myth (Gilgamesh Epos), adapted to fit a monotheistic worldview. |

| Afterlife concept (Sheol) | Mesopotamian underworld beliefs | Early Jewish views of the afterlife echo the shadowy existence in Mesopotamian beliefs about the underworld. |

| Messianic expectations | Canaanite and Persian influence | The concept of a future redeemer draws on Canaanite kingship ideas and Persian eschatological visions of a savior. |

The dialectic of preservation and adaptation

A recurring theme in Judaism’s development is the dialectic between preservation and adaptation. Jewish communities have consistently sought to preserve core elements of their religious identity—such as monotheism, covenant, and Torah observance—while remaining open to external influences that could enrich their understanding and practice of faith. This dynamic process has enabled Judaism to remain both rooted in tradition and responsive to new cultural contexts.

One example of this dialectic is the evolution of Jewish law (halakha). While halakha is grounded in the Torah and Rabbinic interpretation, it has developed over time in response to changing circumstances and external influences. The adaptability of Jewish law has allowed Jewish communities to maintain their distinctiveness while participating in diverse societies.

Conclusion

The constant development of Judaism in relation to external influences underscores the religion’s dynamic and resilient nature. Far from being a closed system, Judaism has evolved through ongoing dialogue with the cultures and philosophies it encountered, resulting in a rich and multifaceted tradition. This interplay of preservation and adaptation not only ensured Judaism’s survival through millennia of exile and dispersion but also contributed to the development of new religious ideas that have had a lasting impact on world history.

References and further reading

- Assmann, Jan, Of God and Gods: Egypt, Israel, and the Rise of Monotheism, 2008, University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN: 978-0299225544

- Grabbe, Lester L., A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period: Volume 1, 2006, T&T Clark, ISBN: 978-0567043528

- Hengel, Martin, Judaism and Hellenism: Studies in their Encounter in Palestine during the Early Hellenistic Period, 2003, Wipf and Stock, ISBN: 978-1592441860

- Tcherikover, Victor, Hellenistic Civilization and the Jews, 1999, Baker Academic, ISBN: 978-0801047855

- Alexander Brungs, Georgi Kapriev, Vilem Mudroch, Die Philosophie des Mittelalters. Bd. 1. Byzanz. Judentum, 2019, Schwabe Verlagsgruppe, ISBN: 9783796526237

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Alexander Brungs, Georgi Kapriev, Vilem Mudroch, Die Philosophie des Mittelalters. Bd. 1. Byzanz. Judentum, 2019, Schwabe Verlagsgruppe, ISBN: 9783796526237

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Hershel Shanks, The Rise Of Ancient Israel, 1992, Biblical Archaeology Society, ISBN: 9781880317075

- Amihay Mazar, Ephraim Stern, Archaeology Of The Land Of The Bible - 10,000-586 B.C.E, 1992, Yale University Press, ISBN: 9780300140071

- Steven Fine, Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman world - Toward a new Jewish archaeology, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521145671

- Richard S. Hess, Israelite Religions - An Archaeological And Biblical Survey, 2007, Baker Academic, ISBN: 9780801027178

- William G. Dever, Beyond The Texts - An Archaeological Portrait Of Ancient Israel And Judah, 2020, SBL Press, ISBN: 9780884144915

- Richard Friedman, Who Wrote The Bible?, 2019, Simon & Schuster, ISBN: 9781501192401

- James Karl Hoffmeier, Akhenaten And The Origins Of Monotheism, 2015, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780199792085

- Jan Assmann, From Akhenaten to Moses - Ancient Egypt and religious change, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9789774166310

- Benjamin D. Sommer, The Bodies Of God And The World Of Ancient Israel, 2009, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521518727

- William G. Dever, Did God have a wife? - Archaeology and folk religion in ancient Israel, 2008, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802863942

- James S. Anderson, Monotheism and Yahweh’s appropriation of Baal, 2015, Bloomsbury T&T Clark, eThe Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies, ISBN: 978-0567683076

- Stephen Mitchell, Peter Van Nuffelen, One God – Pagan monotheism In the Roman Empire, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521194167

- William G. Dever, Who were the early Israelites and where did they come from?, 2006, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802844163

- William M. Schniedewind, How the Bible became a book – The textualization of ancient Israel, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521829465

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bart D. Ehrman, Forged: Writing in the name of God – Why the Bible’s authors are not who we think they are, 2011, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780062012616

- Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus – Apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium, 1999, Oxford University Press on Demand, ISBN: 9780195124736

- Bart D. Ehrman, God’s problem: How the Bible fails to answer our most important question – Why we suffer, 2008, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780061578311

- Israel Knohl, The Messiah Before Jesus - The Suffering Servant Of The Dead Sea Scrolls, 2000, Univ of California Press, ISBN: 9780520215924

comments