The development of the concept of the Messiah in Judaism

The concept of the Messiah (Mashiach, “anointed one”) is one of the most enduring and evolving theological ideas in Judaism, reflecting the dynamic interplay between historical events, theological reflection, and communal aspirations. Rooted in the Hebrew Bible, the messianic idea emerged as a response to the political, social, and spiritual crises faced by the Jewish people, evolving over centuries into a rich and multifaceted tradition. While initially centered on kingship and divine appointment, the concept later expanded to encompass apocalyptic, eschatological, and redemptive dimensions.

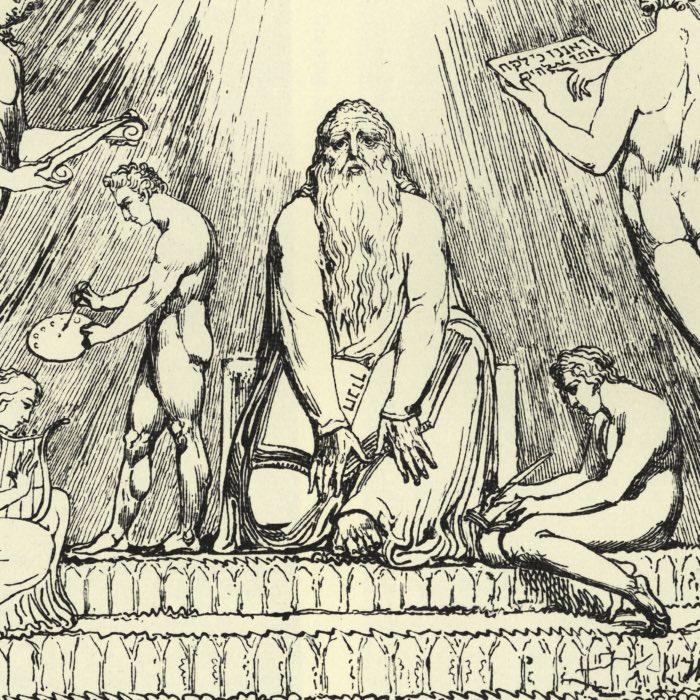

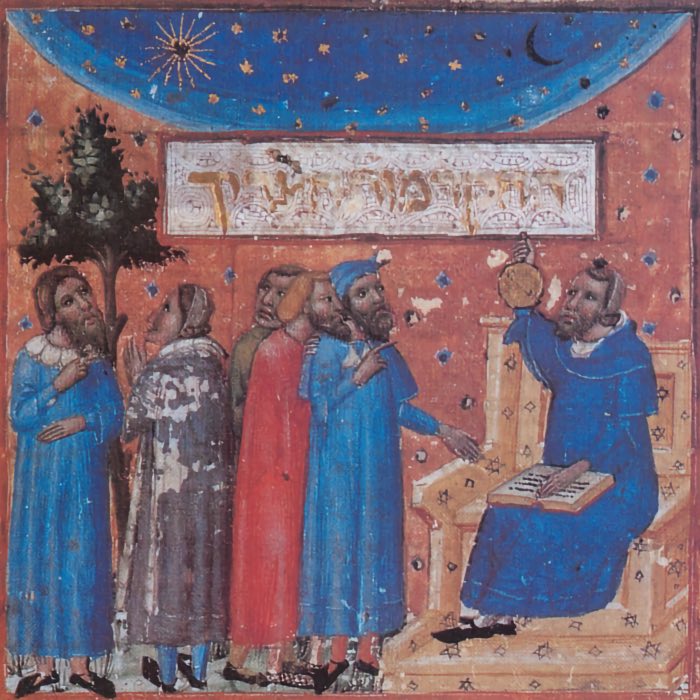

Samuel anoints David, Dura Europos wall painting (detail; see larger detail hereꜛ), Syria, 3rd century CE. The anointing of David as king is a key moment in the development of the messianic concept in Judaism. It symbolizes divine favor and appointment, establishing the Davidic dynasty as a central theme in messianic thought. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Biblical origins: Kingship, anointment, and divine favor

The messianic concept in Judaism finds its origins in the institution of kingship, particularly the anointing of leaders as a symbol of divine favor and authority. The Hebrew Bible frequently uses the term mashiach to refer to anointed individuals, including kings, priests, and prophets, who were consecrated for specific roles in service to God.

The Davidic ideal

The reign of King David (circa 1000 BCE) and the covenantal promise made to him in 2 Samuel 7 became a foundational moment in the development of the messianic idea. God’s promise to establish an everlasting dynasty through David’s lineage gave rise to the belief in a divinely appointed king who would embody justice, righteousness, and peace. This Davidic ideal became a central theme in messianic thought, symbolizing the hope for a future leader who would restore Israel’s fortunes and fulfill the covenantal promises.

Prophetic contributions

The prophets of the Hebrew Bible further shaped the messianic vision, often linking the figure of the Messiah to eschatological and redemptive themes. Isaiah 11:1-9, for example, describes a future ruler from the line of David endowed with wisdom, justice, and the spirit of God. This ruler is depicted as bringing peace and harmony to the world, reflecting both political and cosmic dimensions of messianic hope.

Similarly, texts such as Jeremiah 23:5-6 and Ezekiel 34:23-24 emphasize the role of the Messiah as a shepherd-king who will gather the scattered people of Israel, restore the nation’s independence, and reestablish the covenantal relationship with God.

Second Temple Judaism: Apocalypticism and diverse expectations

The Second Temple period (516 BCE–70 CE) witnessed significant developments in the messianic concept, shaped by the political upheavals and theological ferment of the time. The destruction of the First Temple, the Babylonian exile, and subsequent foreign domination created a context in which messianic hope became increasingly associated with deliverance and divine intervention.

Messianic diversity in Second Temple texts

The literature of the Second Temple period reveals a diversity of messianic expectations, reflecting the varied experiences and aspirations of the Jewish people. Texts such as the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Psalms of Solomon, and apocalyptic writings like 1 Enoch and 4 Ezra offer differing portrayals of the Messiah, ranging from a royal Davidic figure to a priestly or even angelic redeemer.

- Davidic Messiah: Many texts continued to emphasize the role of the Davidic Messiah as a political and military leader who would overthrow foreign oppressors and restore Israel’s sovereignty. This expectation is particularly evident in the Psalms of Solomon 17, which describes a king who will “purge Jerusalem from Gentiles” and establish a just and holy rule.

- Priestly Messiah: In some traditions, particularly among the Essenes, the Messiah is envisioned as a priestly figure who will purify the Temple and restore proper worship. This reflects the growing importance of priestly authority and ritual purity in Second Temple Judaism.

- Apocalyptic Messiah: Apocalyptic literature introduces cosmic and eschatological dimensions to the messianic idea, portraying the Messiah as a heavenly figure who will defeat the forces of evil, inaugurate the end of days, and establish God’s eternal kingdom. Texts such as 1 Enoch and 4 Ezra emphasize the universal scope of messianic redemption, linking it to the final judgment and the renewal of creation.

- Messianism and sectarianism

The diversity of messianic expectations during the Second Temple period contributed to the emergence of sectarian movements within Judaism, each promoting its own interpretation of messianic hope. The Dead Sea Scrolls, for example, reflect the views of the Qumran community, which anticipated the arrival of two messianic figures: a priestly Messiah from the line of Aaron and a royal Messiah from the line of David. This dual-messianic expectation highlights the theological creativity and fragmentation of the period.

Rabbinic Judaism: Redefining the messiah after the temple’s destruction

The destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE and the subsequent dispersion of the Jewish people prompted a reevaluation of messianic expectations. Rabbinic Judaism, which emerged as the dominant expression of Jewish thought in the post-Temple era, reinterpreted the messianic concept in ways that emphasized spiritual resilience and communal continuity.

The Messiah as a future redeemer

Rabbinic literature preserves the hope for a future Messiah, often portraying him as a human descendant of David who will restore Israel, rebuild the Temple, and bring about an era of peace and justice. However, the rabbis downplayed the immediate urgency of messianic fulfillment, instead focusing on the ethical and spiritual responsibilities of the Jewish people in the present.

Ethics and eschatology

The rabbis linked the arrival of the Messiah to the moral and spiritual condition of the Jewish people, emphasizing the role of repentance (teshuvah) and adherence to Torah as prerequisites for redemption. This shift reflects a broader rabbinic strategy of fostering communal resilience and continuity in the face of exile and oppression.

Caution against speculation

The rabbis also expressed caution about messianic speculation, recognizing its potential to destabilize communities and provoke false expectations. In Pirkei Avot (1:2), the rabbis emphasized the centrality of Torah study, worship, and acts of kindness as the pillars of Jewish life, steering attention away from apocalyptic speculation.

Conclusion

The development of the messianic idea reflects a dynamic and evolving tradition that has responded to the historical, theological, and existential challenges faced by the Jewish people. From its biblical roots in the Davidic covenant to its apocalyptic elaboration in Second Temple literature and its reinterpretation in rabbinic thought, the messianic concept has served as a source of hope, resilience, and identity throughout Jewish history.

Beyond its foundational role in Judaism, the messianic idea became a focal point of divergence and dialogue with Christianity, which developed its own interpretation centered on the figure of Jesus of Nazareth. Over time, the concept continued to inspire various religious movements, including Jewish mysticism, Zionism, and Hasidism, each adapting messianic themes to their specific contexts and aspirations.

References and further reading

- Brown, Raymond E., The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, 1999, Anchor Bible Reference Library, ISBN: 978-0385494472

- Israel Knohl, The Messiah Before Jesus - The Suffering Servant Of The Dead Sea Scrolls, 2000, Univ of California Press, ISBN: 9780520215924

- Alexander Brungs, Georgi Kapriev, Vilem Mudroch, Die Philosophie des Mittelalters. Bd. 1. Byzanz. Judentum, 2019, Schwabe Verlagsgruppe, ISBN: 9783796526237

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Richard Friedman, Who Wrote The Bible?, 2019, Simon & Schuster, ISBN: 9781501192401

- James Karl Hoffmeier, Akhenaten And The Origins Of Monotheism, 2015, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780199792085

- Jan Assmann, From Akhenaten to Moses - Ancient Egypt and religious change, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9789774166310

- Benjamin D. Sommer, The Bodies Of God And The World Of Ancient Israel, 2009, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521518727

- William G. Dever, Did God have a wife? - Archaeology and folk religion in ancient Israel, 2008, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802863942

- James S. Anderson, Monotheism and Yahweh’s appropriation of Baal, 2015, Bloomsbury T&T Clark, eThe Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies, ISBN: 978-0567683076

- Stephen Mitchell, Peter Van Nuffelen, One God – Pagan monotheism In the Roman Empire, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521194167

- William G. Dever, Who were the early Israelites and where did they come from?, 2006, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802844163

- William M. Schniedewind, How the Bible became a book – The textualization of ancient Israel, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521829465

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bart D. Ehrman, Forged: Writing in the name of God – Why the Bible’s authors are not who we think they are, 2011, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780062012616

- Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus – Apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium, 1999, Oxford University Press on Demand, ISBN: 9780195124736

- Bart D. Ehrman, God’s problem: How the Bible fails to answer our most important question – Why we suffer, 2008, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780061578311

- Smith, M. S., The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel, 2002, Eerdmans, ISBN: 978-0802839725

- Coogan, M. D., The Oxford History of the Biblical World, 2001, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192802033

- Miller, P. D., The Religion of Ancient Israel, 2007, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN: 978-0664232375

comments