Origins of YHWH and the early monolatry in the Hebrew Bible

The origins of YHWH, the God of Israel, and the early stages of monolatry as expressed in the Tanakh (or Old Testament) form a critical area of study in understanding the development of Jewish theology. The name YHWH first emerges in biblical tradition as the unique deity of the Israelites, but its historical and cultural antecedents suggest a more complex process of religious evolution. Early Israelite religion was not immediately monotheistic but likely began as a form of monolatry — a system in which one deity is exclusively worshiped without denying the existence of others. Over time, this monolatrous devotion to YHWH evolved into the monotheism that characterizes later Jewish thought.

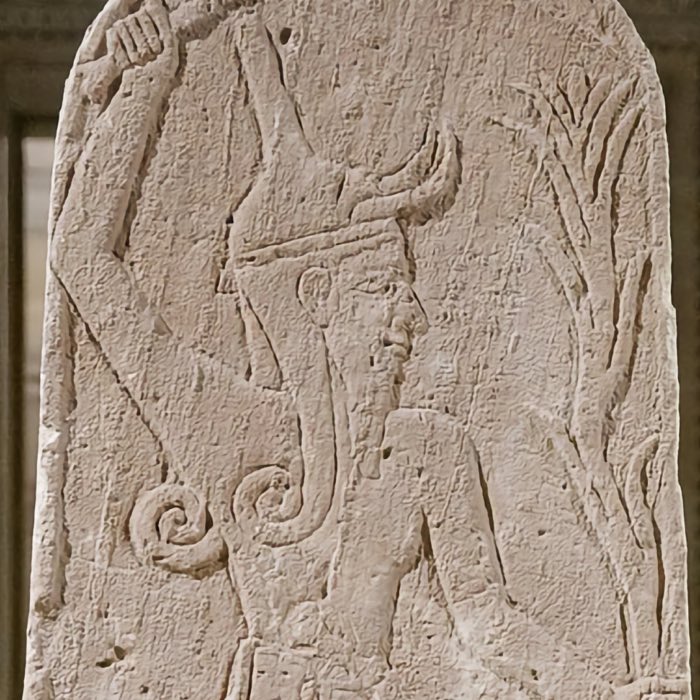

Bronze Statuette of Seated God Ba’al, Hazor, 15th-13th century BCE, Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel. Ba’al was a prominent deity in the Canaanite pantheon and influenced early Israelite religion. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

Origins of YHWH: Historical and etymological insights

The precise origins of YHWH remain a subject of scholarly debate, as the deity’s name and characteristics do not appear in the broader pantheons of Mesopotamia or Canaan in the same way as gods like El, Baal, or Asherah. However, several theories offer plausible explanations for the emergence of YHWH as a distinct deity.

Etymology of YHWH

The name YHWH is derived from the Tetragrammaton, a four-consonant Hebrew root traditionally vocalized as Yahweh. Its exact meaning is debated, but a common interpretation connects it to the Hebrew verb haya (to be), particularly in the context of Exodus 3:14, where God identifies himself to Moses as ehyeh asher ehyeh (“I am who I am” or “I will be who I will be”). This interpretation emphasizes the self-existence and eternality of YHWH.

The Tetragrammaton in Phoenician (12th century BCE to 150 BCE), Paleo-Hebrew (10th century BCE to 135 CE), and square Hebrew (3rd century BCE to present) scripts. It reads from right to left: Yodh, He, Waw, He, meaning YHWH or “I am who I am”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Another view suggests that YHWH’s name may have originated as a theophoric element — a divine name or title embedded in personal or place names — possibly linked to Midianite or Edomite religious traditions. This is supported by biblical passages associating Moses and his father-in-law Jethro, a priest of Midian, with the worship of YHWH (Exodus 18).

The Mesha Stele bears the earliest known reference (840 BCE) to the Israelite god Yahweh. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC-BY-SA 3.0)

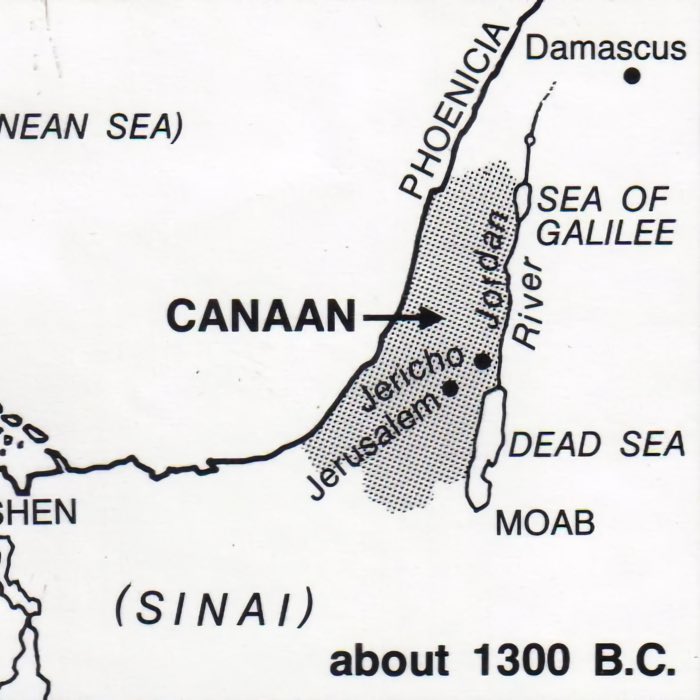

Southern origins: Midian and Edom

Archaeological and textual evidence points to the southern regions of Midian, Edom, and the Sinai Peninsula as significant in the early worship of YHWH. In texts such as Judges 5:4-5 and Deuteronomy 33:2, YHWH is depicted as a deity who comes from the south, specifically from Seir, Paran, or Sinai. These references suggest a connection between YHWH and the southern desert regions, where he may have been venerated as a storm or warrior god associated with volcanic or desert landscapes.

The Midianite hypothesis proposes that the worship of YHWH was introduced to the Israelites through their interactions with southern tribes such as the Midianites or Kenites. This theory is bolstered by the role of Moses as a mediator between these traditions and the emerging Israelite religion.

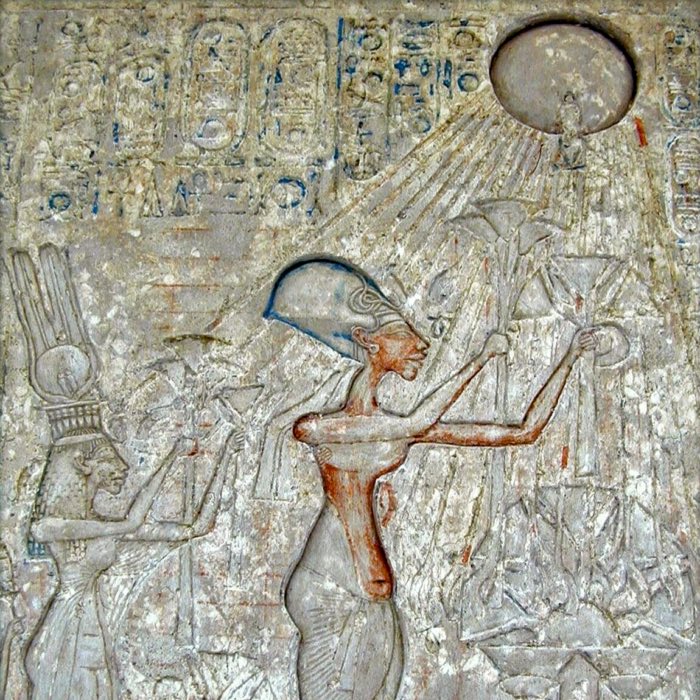

Potential influences of Egyptian beliefs

Scholars have explored the possibility that Egyptian religious concepts may have influenced the development of Israelite theology and the worship of YHWH. During the period traditionally associated with Israelite presence in Egypt, the dominant theological ideas included the worship of Ra, Amun, and other gods in a polytheistic framework, alongside the brief monotheistic experiment under Pharaoh Akhenaten, who elevated Aten, the sun disk, as the sole god. This period of Atenism has drawn particular interest due to its parallels with later Israelite monotheism.

Atenism and early monotheism

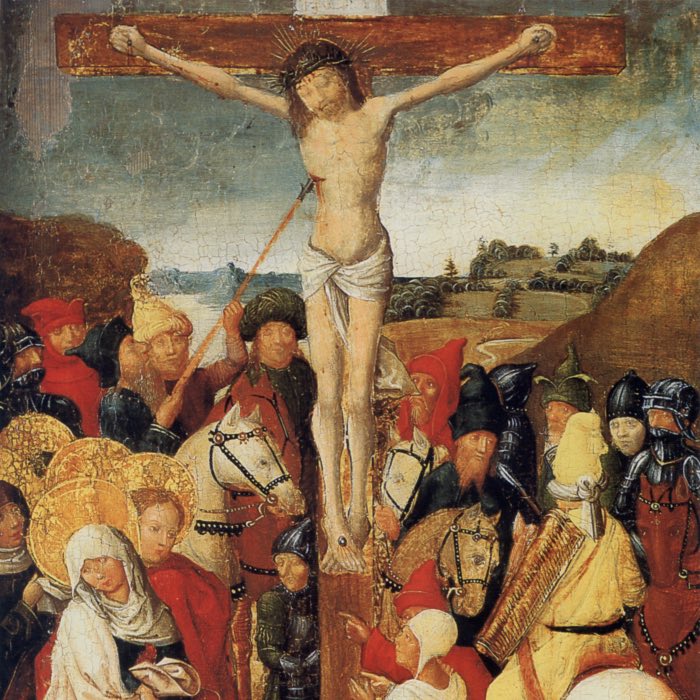

The Amarna period (14th century BCE) under Akhenaten saw a radical shift in Egyptian religion, with Aten being proclaimed as the sole deity. While this experiment was short-lived and largely reversed after Akhenaten’s death, it introduced the concept of a singular divine focus in a polytheistic context. Some scholars propose that memories or remnants of this monotheistic experiment could have influenced the Israelite conception of YHWH as the one true God.

Relief depicting Akhenaten and Nefertiti with three of their daughters under the rays of Aten; Amarna-period, ca. 1350-1340 BCE, limestone. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC-BY-SA 4.0)

The Exodus narrative

The biblical narrative of the Exodus, which describes the Israelites’ liberation from Egypt, may also reflect theological and cultural exchanges. The plagues described in Exodus can be interpreted as symbolic repudiations of specific Egyptian deities, emphasizing YHWH’s supremacy over the gods of Egypt. Additionally, the motif of liberation and covenantal relationship with YHWH could have developed in response to the Israelites’ historical experience in Egypt.

Egyptian symbolism in Israelite worship

Elements of Egyptian religious symbolism appear in early Israelite artifacts and texts. For instance, the cherubim depicted in the Tabernacle and later in Solomon’s Temple may have been inspired by Egyptian iconography, such as the winged figures guarding sacred spaces. The Ark of the Covenant, with its portable shrine design, also bears similarities to Egyptian religious processions.

Early Israelite religion: Monolatry and syncretism

The earliest Israelite religion likely reflected a form of monolatry, in which YHWH was worshiped as the primary deity while the existence of other gods was acknowledged. This stage of religious development is reflected in both archaeological findings and biblical texts, which attest to the coexistence of YHWH worship with elements of Canaanite religion.

Integration with Canaanite religion

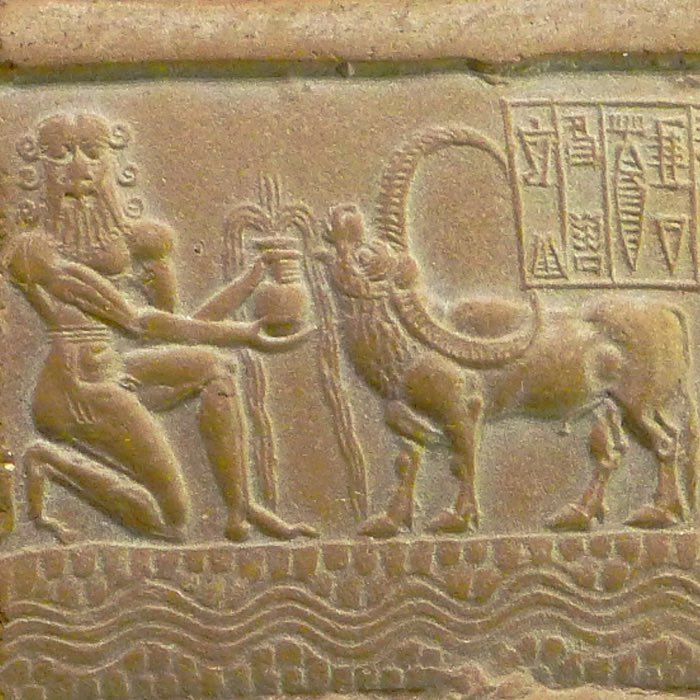

As the Israelites settled in Canaan, their worship of YHWH absorbed and adapted elements of the Canaanite religious framework. The deity El, the high god of the Canaanite pantheon, appears in early Israelite texts as a title or attribute of YHWH. For example, Genesis 33:20 refers to YHWH as El Elohe Yisrael (“El, the God of Israel”), suggesting a merging of YHWH’s identity with that of El.

Similarly, the attributes of Baal, the Canaanite storm god, influenced the depiction of YHWH as a warrior and provider of rain. The biblical imagery of YHWH riding on the clouds (Psalm 68:4) and wielding thunder and lightning echoes Baal’s characteristics, reflecting a period of syncretism in which YHWH’s role was shaped by the religious landscape of Canaan.

Left: Gilded statuette of El from Ugarit. El was a prominent deity in the Canaanite pantheon. He was considered the father of the gods and the creator of the world. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Male votive figure of Baal. This solid cast bronze figurine served as a votive offering, and represents the Canaanite war god, Baal, bringer of the autumnal rains and suppressor of the destructive flood waters. He probably wore a gold skirt and may have carried a mace in one of his clenched fists. Early 2nd millennium BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

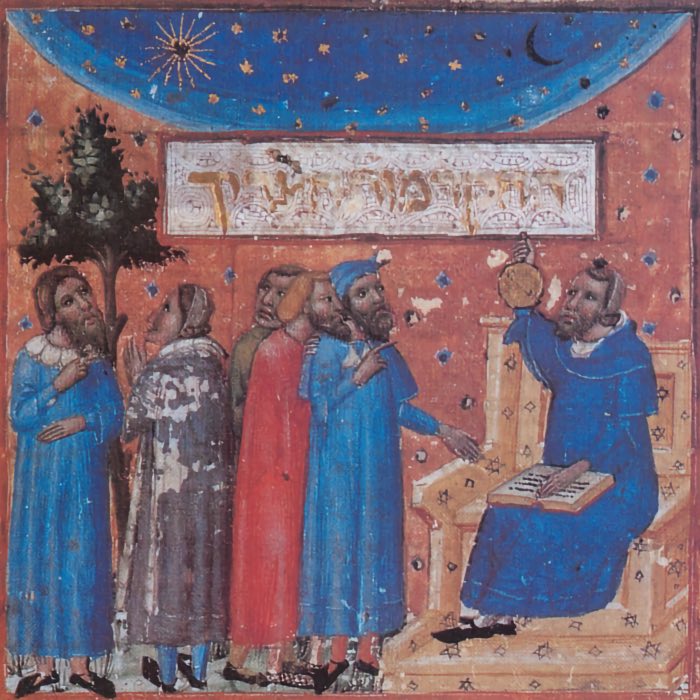

Monolatry in the Tanakh

The Hebrew Bible provides evidence of monolatry in passages that assert YHWH’s supremacy over other gods rather than denying their existence. For instance, Exodus 15:11 asks, “Who is like you, O Lord, among the gods?” implying the presence of other deities while emphasizing YHWH’s unparalleled greatness. Similarly, the first commandment of the Decalogue, “You shall have no other gods before me” (Exodus 20:3), reflects a demand for exclusive worship without explicitly denying the reality of other gods.

Theological innovation: From monolatry to monotheism

The transition from monolatry to monotheism in ancient Israel involved significant theological innovations, driven by historical events, prophetic movements, and the redaction of biblical texts.

The Babylonian exile and the universalization of YHWH

One of the most critical moments in the development of monotheism was the Babylonian exile (586–539 BCE), during which the Israelites faced the destruction of the Temple and the loss of their homeland. This crisis led to a profound rethinking of YHWH’s nature and role, as reflected in the writings of Second Isaiah (Isaiah 40–55).

In these texts, YHWH is depicted as the creator of the entire cosmos, the only true God, and the sovereign ruler of all nations. For example, Isaiah 45:5 declares, “I am the Lord, and there is no other; besides me there is no god.”. This universalization of YHWH marked a decisive break from earlier conceptions of a territorial or national deity, establishing the foundation for Jewish monotheism.

The role of the prophets

Prophetic figures such as Elijah, Hosea, and Jeremiah played a crucial role in promoting exclusive devotion to YHWH and opposing idolatry and syncretism. The prophetic critique of Baal worship and other Canaanite practices emphasized the ethical and covenantal dimensions of YHWH worship, linking religious fidelity to social justice and moral conduct.

Theological codification

The redaction and canonization of biblical texts during and after the Babylonian exile further reinforced monotheism. Priestly and Deuteronomic traditions emphasized YHWH’s uniqueness, the centrality of the covenant, and the rejection of idolatry. These texts reflect a deliberate effort to unify and codify Israelite religion in response to the challenges of exile and diaspora.

Summary

The following table summarizes the stages of YHWH’s development and the evolution of Israelite religion from monolatry to monotheism:

| Stage | Period | Key characteristics | Influences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early polytheism | Pre-12th century BCE | Worship of multiple deities, including El, Baal, and Asherah | Canaanite religion, Mesopotamian beliefs |

| Monolatry | 12th-10th century BCE | Exclusive worship of YHWH while acknowledging other gods | Midianite and Edomite traditions, Canaanite syncretism |

| Early monotheism | 9th-6th century BCE | Emphasis on YHWH’s supremacy and ethical worship | Prophetic movements, regional conflicts, potential Egyptian theological concepts |

| Exilic monotheism | 6th century BCE | Universalization of YHWH as the sole creator and ruler of all | Babylonian exile, Deuteronomic reform |

| Post-exilic monotheism | 5th century BCE onward | Canonization of texts, strict monotheism, rejection of idolatry | Persian influence, priestly redaction |

Conclusion

The origins of YHWH and the development of monolatry in the Hebrew Bible reveal a dynamic process of religious evolution, shaped by historical, cultural, and theological forces. Emerging from the southern regions of the Levant and interacting with Canaanite traditions, YHWH became the central focus of Israelite worship, embodying both continuity with and innovation from the broader religious landscape of the ancient Near East.

The transition from monolatry to monotheism marked a transformative moment in the history of Jewish thought, laying the foundation for the monotheistic traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. By tracing the origins of YHWH and the early stages of Israelite religion, scholars gain insight into the complex interplay of cultural exchange, theological reflection, and historical experience that shaped the religious identity of ancient monotheism.

References and further reading

- Alexander Brungs, Georgi Kapriev, Vilem Mudroch, Die Philosophie des Mittelalters. Bd. 1. Byzanz. Judentum, 2019, Schwabe Verlagsgruppe, ISBN: 9783796526237

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Richard Friedman, Who Wrote The Bible?, 2019, Simon & Schuster, ISBN: 9781501192401

- James Karl Hoffmeier, Akhenaten And The Origins Of Monotheism, 2015, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780199792085

- Jan Assmann, From Akhenaten to Moses - Ancient Egypt and religious change, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9789774166310

- Benjamin D. Sommer, The Bodies Of God And The World Of Ancient Israel, 2009, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521518727

- William G. Dever, Did God have a wife? - Archaeology and folk religion in ancient Israel, 2008, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802863942

- James S. Anderson, Monotheism and Yahweh’s appropriation of Baal, 2015, Bloomsbury T&T Clark, eThe Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies, ISBN: 978-0567683076

- Stephen Mitchell, Peter Van Nuffelen, One God – Pagan monotheism In the Roman Empire, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521194167

- William G. Dever, Who were the early Israelites and where did they come from?, 2006, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802844163

- William M. Schniedewind, How the Bible became a book – The textualization of ancient Israel, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521829465

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bart D. Ehrman, Forged: Writing in the name of God – Why the Bible’s authors are not who we think they are, 2011, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780062012616

- Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus – Apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium, 1999, Oxford University Press on Demand, ISBN: 9780195124736

- Bart D. Ehrman, God’s problem: How the Bible fails to answer our most important question – Why we suffer, 2008, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780061578311

- Israel Knohl, The Messiah Before Jesus - The Suffering Servant Of The Dead Sea Scrolls, 2000, Univ of California Press, ISBN: 9780520215924

- Smith, M. S., The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel, 2002, Eerdmans, ISBN: 978-0802839725

- Coogan, M. D., The Oxford History of the Biblical World, 2001, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192802033

- Miller, P. D., The Religion of Ancient Israel, 2007, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN: 978-0664232375

comments