Origins of the books of the Jewish scriptures

The Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, often perceived as a divinely inspired and immutable text, is in fact the product of centuries of human effort, cultural evolution, and theological reflection. Far from being a monolithic or static creation, the Bible emerged through a dynamic process of oral tradition, textual composition, compilation, and redaction. This process was deeply intertwined with the historical and social developments of ancient Israel and its surrounding cultures. The Bible’s origins reveal it to be a living and evolving work, reflecting the diverse voices, perspectives, and experiences of its authors and editors.

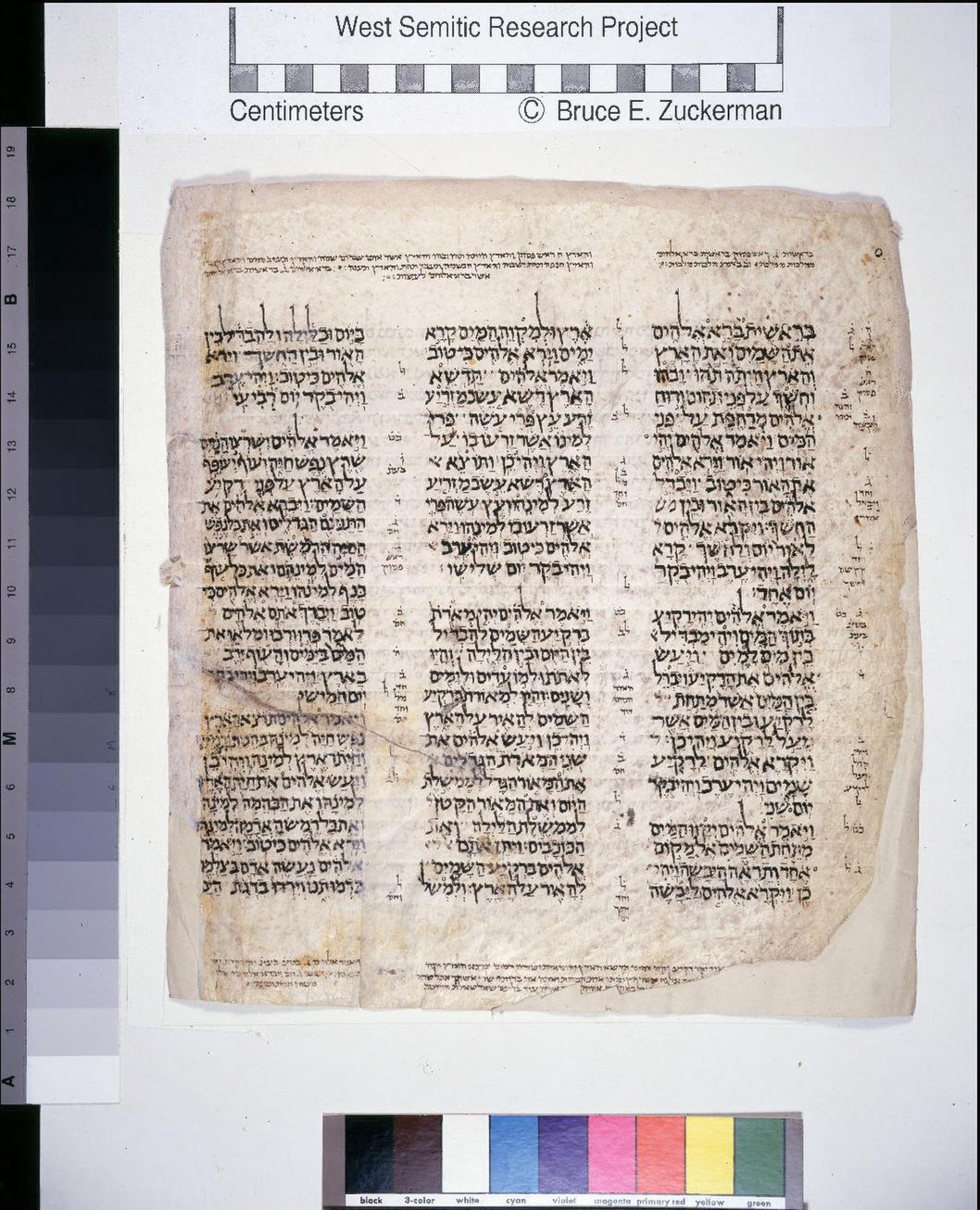

A page from the Codex Leningradensis, the oldest complete manuscript of the Hebrew Bible. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The transition from oral tradition to textualization

The earliest stages of biblical development were rooted in oral traditions. Stories, laws, hymns, and prophecies were transmitted orally within communities, serving as a means of preserving collective memory and identity. These oral traditions were fluid and adaptable, allowing for reinterpretation and adaptation to changing circumstances.

Orality and collective memory

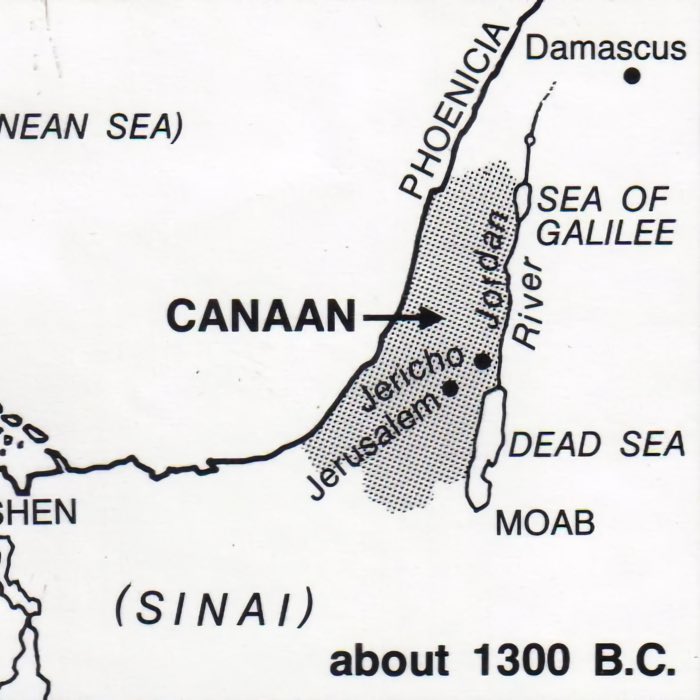

In the ancient Near East, oral traditions played a central role in shaping cultural and religious identity. For early Israel, these traditions encompassed foundational narratives such as the Exodus, the conquest of Canaan, and the establishment of the covenant. These stories were recited and transmitted in communal settings, such as festivals, rituals, and public assemblies, reinforcing their authority and relevance.

The advent of writing

The transition from orality to textualization was not abrupt but occurred over centuries, driven by the adoption of writing technologies and the political centralization of Israel and Judah. Writing allowed for the preservation of traditions in a more fixed form, reducing the variability inherent in oral transmission. The earliest written texts, such as legal codes, royal inscriptions, and cultic regulations, likely served administrative and liturgical purposes before evolving into the narrative and poetic forms found in the Bible.

Historical context and the rise of textualization

The textualization of the Bible was deeply influenced by the historical and political contexts of ancient Israel, including the establishment of monarchies, the Babylonian exile, and the subsequent Persian period. Each of these periods contributed to the collection, editing, and canonization of biblical texts.

The monarchical period

During the reigns of David and Solomon (circa 1000–930 BCE), the establishment of centralized political and religious institutions likely encouraged the creation of written records. Texts such as royal chronicles, genealogies, and temple regulations were produced to legitimize the monarchy and centralize worship in Jerusalem. While these texts do not survive in their original form, their influence is evident in later biblical narratives, such as those in Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles.

The monarchical period also saw the emergence of prophetic traditions, with figures such as Nathan and Gad playing roles in shaping the theological and moral discourse of the time. The writings of later prophets, including Isaiah, Amos, and Hosea, reflect a continuation and expansion of these traditions.

The Babylonian exile

The destruction of Jerusalem and the Babylonian exile (586–539 BCE) marked a turning point in the textualization of the Bible. The loss of the temple and the dispersion of the population created a crisis of identity that spurred the collection and preservation of sacred traditions. Texts such as the Deuteronomic history (Deuteronomy through Kings) and the priestly traditions in the Torah were likely compiled during this period, reflecting efforts to reinterpret Israel’s history and covenant in light of the exile.

The exile also fostered the development of synagogue worship and the study of sacred texts as a means of sustaining communal identity. The shift from temple-based to text-based religion had profound implications for the formation of the Hebrew Bible.

The Persian period and canon formation

The return from exile under Persian rule (539–332 BCE) provided the conditions for the further compilation and canonization of biblical texts. The rebuilding of the temple under Ezra and Nehemiah was accompanied by efforts to codify the Torah as the foundation of Jewish identity and law. The Persian administration’s support for local autonomy through religious law likely encouraged this process, leading to the elevation of the Torah as the core of Jewish scripture.

The role of redaction and compilation

The formation of the Hebrew Bible was not a linear process but involved multiple stages of redaction and compilation, reflecting diverse theological perspectives and historical contexts. The final form of many biblical texts represents a synthesis of earlier traditions, often incorporating competing voices and viewpoints.

The documentary hypothesis

The Pentateuch, or Torah, illustrates the complexity of redaction in biblical composition. The Documentary Hypothesis, first articulated by Julius Wellhausen, posits that the Pentateuch is composed of four main sources — J (Yahwist), E (Elohist), D (Deuteronomic), and P (Priestly) — each reflecting distinct theological and historical contexts. These sources were gradually woven together by redactors to create a unified narrative, albeit one that retains traces of its composite origins.

Chronicles and the deuteronomistic history

The books of Chronicles and the Deuteronomistic history (Joshua through Kings) provide another example of editorial activity. Chronicles reinterprets earlier traditions, emphasizing themes of divine faithfulness and the centrality of the temple, while the Deuteronomistic history offers a more critical perspective on Israel’s failures and the consequences of covenantal disobedience. Both reflect the theological priorities of their respective communities and periods.

The Bible as a dynamic and unfinished work

The textualization of the Hebrew Bible was not a single event but an ongoing process that continued into the Second Temple period and beyond. The canonization of the Hebrew Bible, solidified by the first century CE, did not mark the end of its interpretive life. Instead, it served as the foundation for ongoing engagement and reinterpretation in Jewish and later Christian traditions.

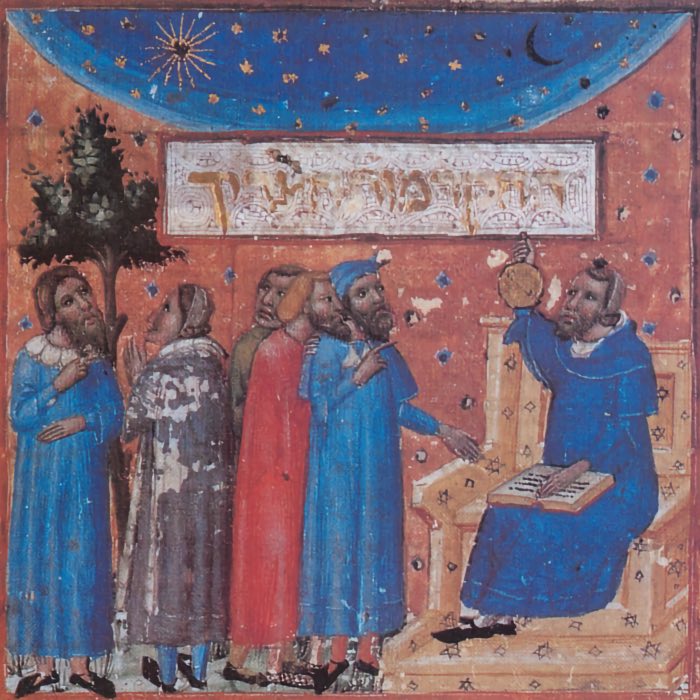

Midrash and Rabbinic interpretation

The dynamic nature of the Bible is evident in the tradition of midrash, which explores the gaps and ambiguities in the biblical text to generate new meanings and applications. Rabbinic literature demonstrates how the Bible continued to evolve as a living document, responding to new historical and cultural contexts.

Theological implications

Understanding the Bible as a dynamic and humanly mediated work does not diminish its theological significance. Instead, it highlights the ways in which divine revelation operates through human history, culture, and creativity. The process of textualization reflects the collaborative nature of faith, inviting successive generations to participate in the ongoing interpretation and application of sacred texts.

Conclusion

The origins of the Hebrew Bible reveal it to be a dynamic and evolving work, shaped by centuries of oral tradition, textual composition, and redaction. Far from being a static product of divine fiat, the Bible reflects the complex interplay of human agency and religious thought, responding to the historical, social, and theological challenges of its time.

Writing a Torah scroll. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

References and further reading

- Alexander Brungs, Georgi Kapriev, Vilem Mudroch, Die Philosophie des Mittelalters. Bd. 1. Byzanz. Judentum, 2019, Schwabe Verlagsgruppe, ISBN: 9783796526237

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Richard Friedman, Who Wrote The Bible?, 2019, Simon & Schuster, ISBN: 9781501192401

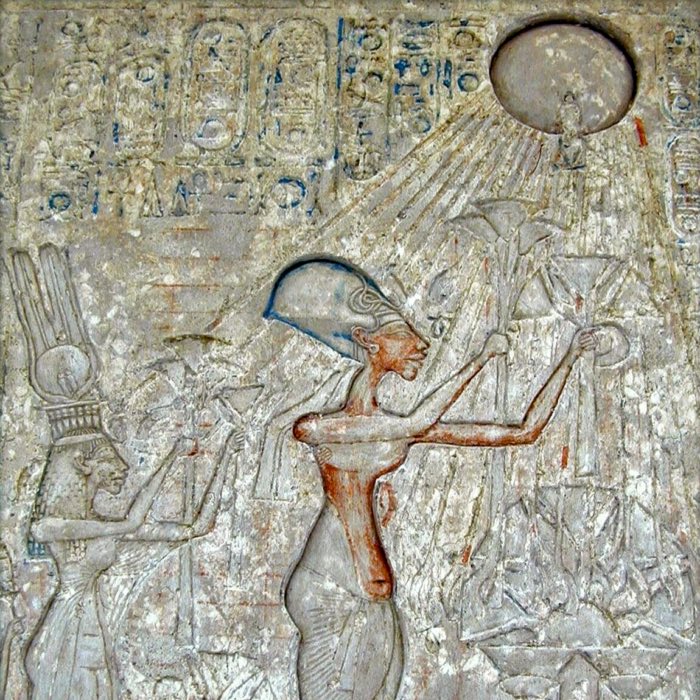

- James Karl Hoffmeier, Akhenaten And The Origins Of Monotheism, 2015, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780199792085

- Jan Assmann, From Akhenaten to Moses - Ancient Egypt and religious change, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9789774166310

- Benjamin D. Sommer, The Bodies Of God And The World Of Ancient Israel, 2009, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521518727

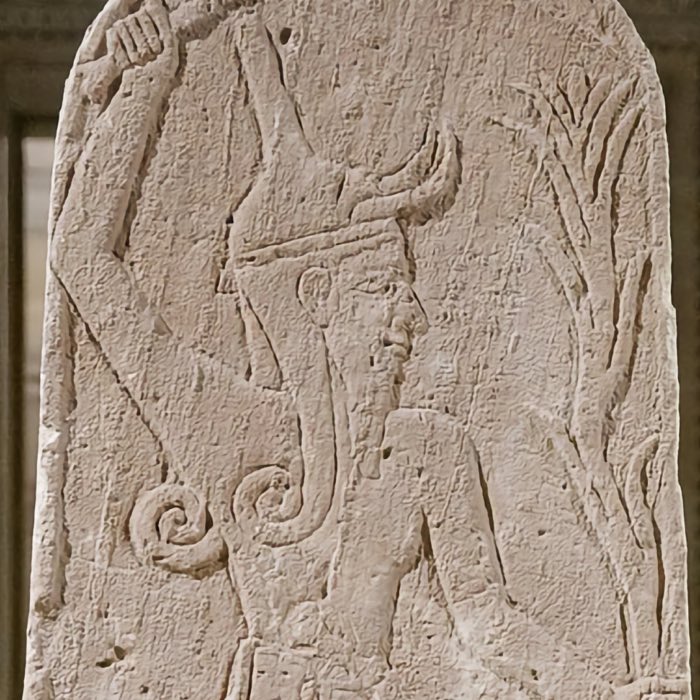

- William G. Dever, Did God have a wife? - Archaeology and folk religion in ancient Israel, 2008, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802863942

- James S. Anderson, Monotheism and Yahweh’s appropriation of Baal, 2015, Bloomsbury T&T Clark, eThe Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies, ISBN: 978-0567683076

- Stephen Mitchell, Peter Van Nuffelen, One God – Pagan monotheism In the Roman Empire, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521194167

- William G. Dever, Who were the early Israelites and where did they come from?, 2006, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802844163

- William M. Schniedewind, How the Bible became a book – The textualization of ancient Israel, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521829465

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bart D. Ehrman, Forged: Writing in the name of God – Why the Bible’s authors are not who we think they are, 2011, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780062012616

- Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus – Apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium, 1999, Oxford University Press on Demand, ISBN: 9780195124736

- Bart D. Ehrman, God’s problem: How the Bible fails to answer our most important question – Why we suffer, 2008, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780061578311

- Israel Knohl, The Messiah Before Jesus - The Suffering Servant Of The Dead Sea Scrolls, 2000, Univ of California Press, ISBN: 9780520215924

- Smith, M. S., The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel, 2002, Eerdmans, ISBN: 978-0802839725

- Coogan, M. D., The Oxford History of the Biblical World, 2001, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192802033

- Miller, P. D., The Religion of Ancient Israel, 2007, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN: 978-0664232375

comments