The consequence of the Babylonian exile: The placeless god and a religious revolution

The Babylonian exile (586–539 BCE) stands as one of the most transformative events in the history of ancient Israel and the development of its religion. This period, marked by the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem and the forced displacement of the Judean elite to Babylon, presented an existential crisis for the exiled community. The loss of the Temple, the central locus of worship and divine presence, necessitated a rethinking of theological concepts and religious practices. The result was a revolutionary shift in the conception of God and the nature of worship, with YHWH emerging as a “placeless” deity — one no longer bound to a physical sanctuary or specific geographical location. This theological innovation had profound implications for the development of Judaism and later monotheistic traditions, as it marked a departure from the territorial and cultic structures typical of ancient Near Eastern religions.

Depiction of the Babylonian exile, with the Ishtar Gate (one of the city gates of Babylon) and Jerusalem in flames. Assyrian wall carving, from Nineveh, South West Palace 790 - 592 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Historical context: The Babylonian exile and its challenges

The Babylonian exile followed the conquest of the Kingdom of Judah by Nebuchadnezzar II in 586 BCE. The destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple was not only a political and cultural catastrophe but also a theological crisis. In the ancient Near East, temples were seen as the earthly dwelling places of the gods, and the destruction of a temple was often interpreted as the defeat of the deity it housed.

The Flight of the Prisoners, c. 1896-1902, by Joseph Tissot. The painting depicts the deportation and exile of the Jews of the ancient Kingdom of Judah to Babylon and the destruction of Jerusalem and Solomon’s temple. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

For the Judeans, the loss of the Temple in Jerusalem raised profound questions about YHWH’s power, presence, and covenantal promises. How could YHWH, the God of Israel, be worshiped without a temple? Had He been defeated by the Babylonian gods, as many ancient Near Eastern frameworks would suggest? These challenges prompted a reevaluation of YHWH’s nature and the dynamics of the covenant.

Waters of Babylon, Gebhard Fugel, 1920. Jews sit on the banks of the Tigris, which flows through Babylon, and remembering Jerusalem. Psalm 137 about this event: “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion. If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning.”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Theological innovation: The emergence of the placeless god

In response to the exile, Judean thinkers and religious leaders developed a radical reinterpretation of YHWH’s identity, emphasizing his transcendence and universal sovereignty. This theological innovation can be seen as a reaction to the limitations of traditional territorial and temple-based conceptions of the divine.

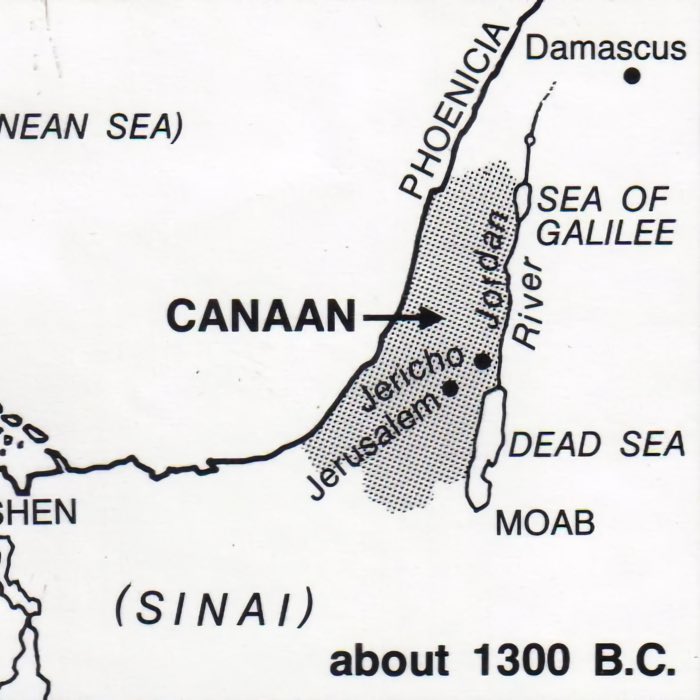

From a territorial god to a universal deity

In pre-exilic theology, YHWH was often understood as the national deity of Israel, associated with the land of Canaan and particularly with Jerusalem and its Temple. While He was acknowledged as supreme among the gods (as in monolatry), his presence was closely tied to specific sacred spaces.

The exile disrupted this territorial framework, leading to the affirmation of YHWH as a universal God whose presence and power extended beyond any single location. Prophetic texts such as Second Isaiah (Isaiah 40–55) articulate this vision of YHWH’s universal sovereignty. Isaiah 66:1 declares, “Heaven is my throne, and the earth is my footstool. What is the house that you would build for me?” This proclamation reflects the theological shift from a localized to a cosmic understanding of God.

Theological decentralization and worship

The exile also necessitated new forms of worship and community organization, as the sacrificial rituals central to Temple worship were no longer possible. This shift led to the emergence of synagogue gatherings, the centrality of prayer, and the study of sacred texts as alternative means of maintaining religious identity and connection to YHWH. These developments underscored the idea that God’s presence was not confined to a physical sanctuary but could be accessed through communal and individual devotion.

YHWH as a god of history and covenant

The exilic prophets emphasized YHWH’s role as the Lord of history, who used the Babylonian conquest as a means of disciplining his people and fulfilling his purposes. This interpretation reframed the exile not as a defeat of YHWH but as an expression of his justice and covenantal faithfulness. Texts such as Jeremiah 29:10-14 and Ezekiel 36:22-28 present the exile as a temporary phase in YHWH’s plan, with the promise of restoration reinforcing his enduring commitment to his people.

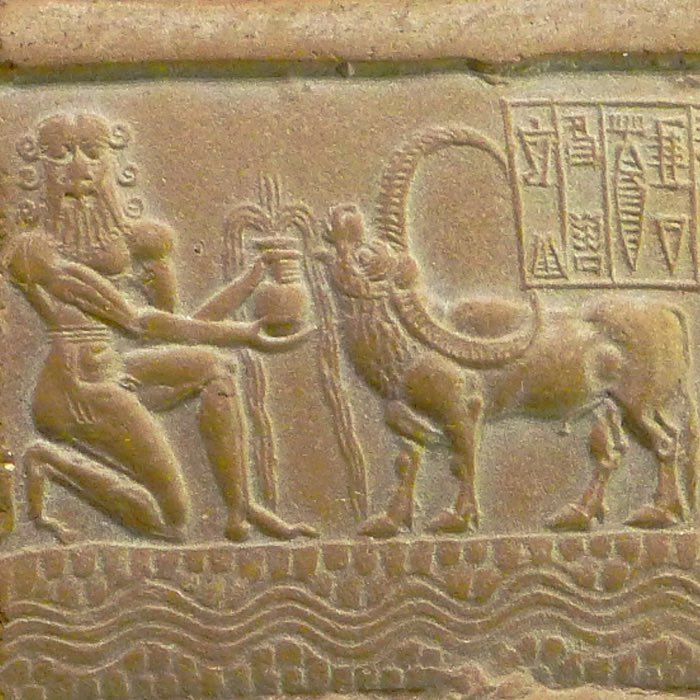

Contrasts with Mesopotamian religions: A unique theological vision

The development of the concept of a placeless God set Israelite religion apart from the broader religious landscape of the ancient Near East. In Mesopotamian religions, deities were typically associated with specific cities, temples, and geographic regions. For example, Marduk was inseparably linked to Babylon, and his power was demonstrated through the grandeur of the Esagila temple.

By contrast, the exilic theology of YHWH presented a deity who transcended geographic and architectural boundaries. This shift allowed the exiled community to maintain its identity and faith while adapting to the realities of displacement and diaspora. It also laid the groundwork for the eventual emergence of Judaism as a portable and text-centered religion, capable of thriving in diverse cultural and geographic contexts.

The legacy of the placeless God in post-exilic and later traditions

The theological innovations of the Babylonian exile had lasting implications for the development of Judaism and later monotheistic traditions. The concept of a placeless God not only enabled the restoration of religious life in the post-exilic period but also shaped the foundations of rabbinic Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Second Temple period

The return from exile and the rebuilding of the Temple under Persian sponsorship did not negate the theological advances made during the exile. Instead, these advances enriched the religious life of the restored community. The Second Temple itself was understood as a symbol of YHWH’s covenantal presence rather than a limitation on his universal sovereignty.

Diaspora Judaism

The placeless God concept became particularly significant for Jewish communities living in the diaspora during the Hellenistic and Roman periods. The emphasis on prayer, ethical conduct, and the study of Torah allowed Jewish identity and worship to flourish without reliance on a central sanctuary.

Christianity and Islam

The universalistic vision of YHWH developed during the exile influenced the theological frameworks of both Christianity and Islam. In Christianity, the concept of God’s universal presence was expanded through the teachings of Jesus and the missionary efforts of the early Church. In Islam, the idea of a single, transcendent God who is not confined to any particular place is central to the Qur’anic vision of Allah.

Conclusion

The Babylonian exile catalyzed a revolutionary shift in the theological understanding of YHWH, transforming Him from a territorial deity into a universal and placeless God. This innovation not only addressed the immediate challenges of exile but also laid the foundation for a dynamic and enduring religious tradition. By embracing a vision of God that transcended geographic and architectural constraints, the exilic community ensured the resilience and adaptability of their faith, shaping the trajectory of monotheism for millennia.

References and further reading

- Alexander Brungs, Georgi Kapriev, Vilem Mudroch, Die Philosophie des Mittelalters. Bd. 1. Byzanz. Judentum, 2019, Schwabe Verlagsgruppe, ISBN: 9783796526237

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Richard Friedman, Who Wrote The Bible?, 2019, Simon & Schuster, ISBN: 9781501192401

- James Karl Hoffmeier, Akhenaten And The Origins Of Monotheism, 2015, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780199792085

- Jan Assmann, From Akhenaten to Moses - Ancient Egypt and religious change, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9789774166310

- Benjamin D. Sommer, The Bodies Of God And The World Of Ancient Israel, 2009, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521518727

- William G. Dever, Did God have a wife? - Archaeology and folk religion in ancient Israel, 2008, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802863942

- James S. Anderson, Monotheism and Yahweh’s appropriation of Baal, 2015, Bloomsbury T&T Clark, eThe Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies, ISBN: 978-0567683076

- Stephen Mitchell, Peter Van Nuffelen, One God – Pagan monotheism In the Roman Empire, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521194167

- William G. Dever, Who were the early Israelites and where did they come from?, 2006, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802844163

- William M. Schniedewind, How the Bible became a book – The textualization of ancient Israel, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521829465

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bart D. Ehrman, Forged: Writing in the name of God – Why the Bible’s authors are not who we think they are, 2011, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780062012616

- Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus – Apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium, 1999, Oxford University Press on Demand, ISBN: 9780195124736

- Bart D. Ehrman, God’s problem: How the Bible fails to answer our most important question – Why we suffer, 2008, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780061578311

- Israel Knohl, The Messiah Before Jesus - The Suffering Servant Of The Dead Sea Scrolls, 2000, Univ of California Press, ISBN: 9780520215924

- Smith, M. S., The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel, 2002, Eerdmans, ISBN: 978-0802839725

- Coogan, M. D., The Oxford History of the Biblical World, 2001, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192802033

- Miller, P. D., The Religion of Ancient Israel, 2007, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN: 978-0664232375

comments