The concept of sin in Judaism and its central emphasis

The concept of sin (chet) in Judaism is deeply embedded within its theological framework, serving as a pivotal element in the relationship between humanity and YHWH. Rooted in the covenantal relationship established in the Torah, sin is understood as a deviation from the divine will, a breach of the moral and legal obligations set forth in Jewish law (halakhah). Unlike some religious traditions that view sin primarily as an inherent flaw or state of being, Judaism conceptualizes sin in dynamic and relational terms, emphasizing human agency, repentance, and the possibility of reconciliation.

Cain slaying Abel, by Peter Paul Rubens, c. 1600. The story of Cain and Abel is one of the earliest narratives in the Hebrew Bible, illustrating the consequences of sin and the nature of human moral responsibility. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The origins of sin in the Hebrew scriptures

The Hebrew Bible introduces the concept of sin as an act of disobedience or transgression against God’s commandments. The narratives, laws, and prophetic writings of the Bible present sin in various forms, ranging from individual failings to collective violations, each carrying profound moral and theological implications.

Sin as missing the mark

The Hebrew word most commonly translated as “sin” is chet, derived from a root meaning “to miss the mark.” This term conveys the idea of failing to align one’s actions with the divine will. In this sense, sin is not an inherent state but a specific act or choice that disrupts the intended harmony between humanity, God, and creation.

The story of Cain and Abel (Genesis 4:1-16) exemplifies this understanding of sin. God warns Cain, “Sin is crouching at your door; it desires to have you, but you must rule over it” (Genesis 4:7). Here, sin is depicted as a force that must be resisted, emphasizing human agency and moral responsibility.

Sin and covenant

In the biblical worldview, sin is primarily understood in the context of the covenant between God and Israel. The covenant, established at Sinai, outlines the moral and legal obligations that Israel must uphold as God’s chosen people. Sin, therefore, represents a breach of this covenant, disrupting the relationship between God and the community.

The Decalogue (Ten Commandments) and the broader corpus of Torah law define the parameters of righteous living, addressing both ethical conduct and ritual obligations. Violations of these laws, whether intentional or unintentional, are categorized as sins with varying degrees of severity and consequences.

Part of the All Souls Deuteronomy, containing the oldest extant copy of the Decalogue (Ten Commandments) from the Hebrew Bible. It is dated to the early Herodian period, between 30 and 1 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Collective responsibility and national sin

The Hebrew Bible also addresses the concept of collective sin, where the actions of the community as a whole lead to divine judgment. The prophetic literature frequently emphasizes this theme, with prophets such as Amos, Isaiah, and Jeremiah condemning social injustice, idolatry, and covenantal unfaithfulness. The Babylonian exile is portrayed as a consequence of Israel’s collective sins, highlighting the interconnectedness of individual and communal responsibility.

Rabbinic interpretations: Expanding the Concept of sin

The rabbis of the Talmudic and post-Talmudic periods expanded and refined the biblical concept of sin, integrating it into a broader philosophical and legal framework. Rabbinic thought emphasizes the interplay between divine justice, human free will, and the potential for repentance (teshuvah).

Sin as a legal and ethical violation

Rabbinic literature categorizes sins into various types, including mitzvot aseh (positive commandments) and mitzvot lo ta’aseh (negative commandments). Violations of these commandments are further classified based on intent (e.g., inadvertent vs. deliberate) and the nature of the transgression (e.g., ritual vs. ethical). This detailed categorization reflects the rabbis’ commitment to integrating theological principles with practical legal reasoning.

The Mishnah and Talmud discuss specific examples of sin and their remedies, emphasizing the role of halakhah in guiding ethical behavior. For instance, Masechet Yoma explores the process of atonement on Yom Kippur, detailing the steps required to achieve forgiveness for various types of sins.

The Yetzer Hara and Yetzer Hatov

Rabbinic thought introduces the concept of the yetzer hara (evil inclination) and yetzer hatov (good inclination) as forces within the human soul that influence moral decision-making. The yetzer hara is not inherently evil but represents natural desires and impulses that, if left unchecked, can lead to sin. The rabbis emphasize the importance of self-discipline, Torah study, and communal support in overcoming the yetzer hara and cultivating the yetzer hatov.

Teshuvah: The path to reconciliation

A central innovation of rabbinic theology is the emphasis on teshuvah (repentance) as a means of rectifying sin and restoring the relationship with God. The process of teshuvah involves three key steps: recognition of the sin (hakara), remorse (charatah), and a commitment to change (kabalah al ha’atid). Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, serves as the culmination of this process, providing an annual opportunity for communal and individual reflection and reconciliation.

The Jewish tabernacle and priesthood, George C. Needham, 1874. The painting shows the High Priest on Yom Kippur. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The rabbinic emphasis on teshuvah underscores the possibility of transformation and renewal, portraying sin not as an insurmountable barrier but as an opportunity for spiritual growth.

Theological dimensions of sin in Judaism

The concept of sin in Judaism is deeply intertwined with its theological principles, reflecting the covenantal relationship between God and humanity, the balance between justice and mercy, and the role of divine forgiveness.

Justice and mercy

Jewish theology emphasizes the tension between divine justice (din) and mercy (rachamim). While God is portrayed as a just judge who holds individuals accountable for their actions, He is also depicted as compassionate and forgiving. Texts such as Exodus 34:6-7 describe God as “abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness”, highlighting His willingness to forgive those who sincerely repent.

This balance between justice and mercy is reflected in rabbinic teachings, which assert that God’s mercy often tempers His judgment, allowing for the possibility of forgiveness and redemption.

Covenantal faithfulness and divine forgiveness

Sin in Judaism is ultimately understood in relational terms, as a breach of the covenantal bond between God and His people. The concept of divine forgiveness is central to this relationship, emphasizing God’s enduring faithfulness and His desire for humanity to return to Him. The prophetic literature often portrays God as a loving parent or spouse, willing to forgive Israel’s transgressions and renew the covenant.

Practical implications: Sin, ethics, and community

The concept of sin in Judaism extends beyond theological abstraction, shaping ethical behavior and communal life. Jewish teachings on sin emphasize accountability, the importance of ethical conduct, and the role of community in supporting moral and spiritual growth.

Accountability and responsibility

Judaism places a strong emphasis on individual and collective responsibility for sin. This responsibility includes not only acknowledging one’s own failings but also addressing the consequences of sin within the community. The principle of arvut (mutual responsibility) underscores the interconnectedness of individuals within the covenantal community.

Ethical conduct and social justice

The focus on sin as a breach of ethical obligations highlights the centrality of justice, compassion, and integrity in Jewish life. The prophetic critique of social injustice and the rabbinic emphasis on ethical behavior reflect a commitment to aligning human actions with divine values.

Ritual and reflection

Jewish rituals, such as Yom Kippur and the recitation of the Vidui (confessional prayer), provide structured opportunities for reflecting on sin and seeking forgiveness. These practices reinforce the communal and relational dimensions of sin, emphasizing the importance of humility, introspection, and reconciliation.

Christian interpretation of sin and its relationship to Jewish thought

In Christianity, the concept of sin shares similarities with the Jewish understanding but introduces key theological distinctions, particularly regarding human nature, redemption, and the role of Jesus.

Original sin and human nature

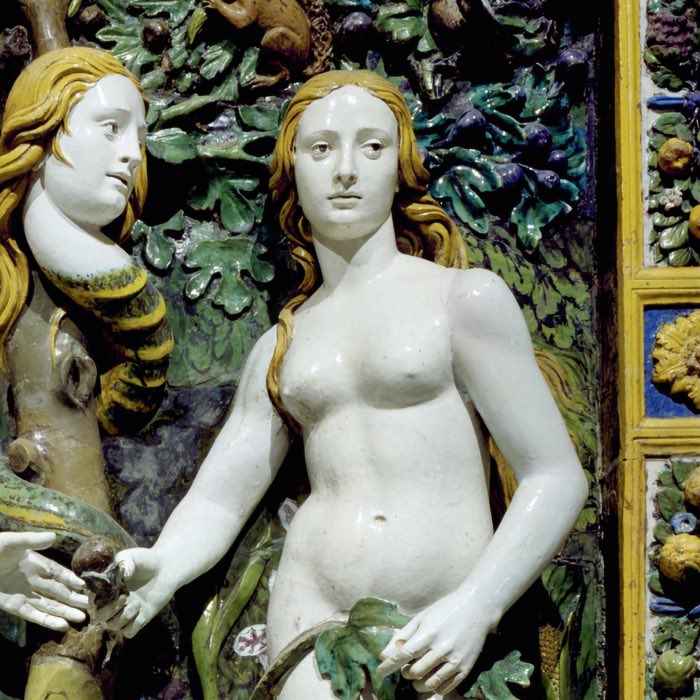

One major difference lies in the doctrine of original sin, articulated by early Christian theologians such as Augustine of Hippo. According to this doctrine, humanity inherited a sinful nature due to Adam and Eve’s transgression in the Garden of Eden. This contrasts with the Jewish view, which does not emphasize inherited sin but rather focuses on individual responsibility and the capacity for moral choice.

One of the earliest depictions of Adam and Eve, from catacombs of Saints Marcellinus and Peter, Rome, 4th century. This catacomb is located on the Via Labicana near a villa of Constantine (r. 306-337 CE). The motif of Adam and Eve is a common theme in early Christian art, symbolizing the fall of humanity and the promise of redemption. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

While Judaism sees sin as an act of “missing the mark” that can be corrected through repentance, Christianity often views sin as an inherent condition that requires divine grace for redemption.

The role of Jesus and atonement

A central element of Christian theology is the belief that Jesus’ sacrificial death and resurrection provide atonement for humanity’s sins. In Christian thought, Jesus is seen as the ultimate means of reconciling humanity with God. This contrasts with the Jewish emphasis on teshuvah and Yom Kippur as ongoing processes of repentance and atonement.

Despite these differences, both traditions share a belief in the possibility of forgiveness and the importance of ethical behavior. The emphasis on divine mercy and human responsibility is present in both frameworks, though they differ in their mechanisms for achieving reconciliation with God.

Ethical implications and communal responsibility

Both Judaism and Christianity stress the importance of ethical conduct and communal support in addressing sin. While Jewish teachings emphasize adherence to halakhah and mutual responsibility within the covenantal community, Christian ethics often focus on the principles of love, grace, and service to others.

In practice, both traditions call for introspection, humility, and efforts to improve oneself and the community. The Jewish practice of Yom Kippur and the Christian practice of confession and penance serve as structured means of reflecting on sin and seeking reconciliation.

Similarities in moral teachings

Despite theological differences, there are significant overlaps in the moral teachings of Judaism and Christianity. Both traditions uphold principles such as justice, compassion, and integrity, drawing on shared scriptural foundations. The prophetic calls for social justice in the Hebrew Bible resonate with Christian teachings on love and service.

Conclusion

The concept of sin in Judaism is a rich and multifaceted element of its theological and ethical framework. Rooted in the covenantal relationship between God and humanity, sin is understood as a deviation from divine will that disrupts both individual and communal harmony. Through its emphasis on human agency, repentance, and divine forgiveness, Judaism presents a vision of sin that is both challenging and redemptive. The later emerged Christianity, on the other hand, introduces the doctrine of original sin and highlights the necessity of divine grace for redemption through Jesus Christ. Despite these theological differences, both traditions underscore the importance of ethical conduct, communal responsibility, and the pursuit of reconciliation with the divine.

References and further reading

- Alexander Brungs, Georgi Kapriev, Vilem Mudroch, Die Philosophie des Mittelalters. Bd. 1. Byzanz. Judentum, 2019, Schwabe Verlagsgruppe, ISBN: 9783796526237

- Walter Dietrich, Hans-Peter Mathys, Thomas Römer, Rudolf Smend, Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments, 2014, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, ISBN: 9783170203549

- Richard Friedman, Who Wrote The Bible?, 2019, Simon & Schuster, ISBN: 9781501192401

- James Karl Hoffmeier, Akhenaten And The Origins Of Monotheism, 2015, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780199792085

- Jan Assmann, From Akhenaten to Moses - Ancient Egypt and religious change, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9789774166310

- Benjamin D. Sommer, The Bodies Of God And The World Of Ancient Israel, 2009, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521518727

- William G. Dever, Did God have a wife? - Archaeology and folk religion in ancient Israel, 2008, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802863942

- James S. Anderson, Monotheism and Yahweh’s appropriation of Baal, 2015, Bloomsbury T&T Clark, eThe Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies, ISBN: 978-0567683076

- Stephen Mitchell, Peter Van Nuffelen, One God – Pagan monotheism In the Roman Empire, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521194167

- William G. Dever, Who were the early Israelites and where did they come from?, 2006, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN: 9780802844163

- William M. Schniedewind, How the Bible became a book – The textualization of ancient Israel, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521829465

- Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament – A historical introduction to the early Christian writings, 2000, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN: 9780195126396

- Bart D. Ehrman, Forged: Writing in the name of God – Why the Bible’s authors are not who we think they are, 2011, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780062012616

- Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus – Apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium, 1999, Oxford University Press on Demand, ISBN: 9780195124736

- Bart D. Ehrman, God’s problem: How the Bible fails to answer our most important question – Why we suffer, 2008, HarperOne, ISBN: 9780061578311

- Israel Knohl, The Messiah Before Jesus - The Suffering Servant Of The Dead Sea Scrolls, 2000, Univ of California Press, ISBN: 9780520215924

- Smith, M. S., The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel, 2002, Eerdmans, ISBN: 978-0802839725

- Coogan, M. D., The Oxford History of the Biblical World, 2001, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192802033

- Miller, P. D., The Religion of Ancient Israel, 2007, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN: 978-0664232375

comments