Archaeological evidence of the Israelites

The search for archaeological evidence of the Israelites — an ancient people whose narratives form the backbone of the Hebrew Bible — has long fascinated scholars and researchers. Archaeology provides a lens through which to understand the historical context of the Israelites, offering insights into their origins, settlement patterns, culture, and interactions with neighboring civilizations. However, the interpretation of archaeological data in relation to the biblical narrative remains a complex and often contentious field, shaped by differing methodologies, theoretical frameworks, and historical assumptions. In this post, we examine the archaeological evidence associated with the Israelites, focusing on their emergence in the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age (circa 1200–1000 BCE) in the Levant, their settlement in the central highlands, and their cultural and material practices. We also discuss the challenges and debates that arise in correlating archaeological findings with the biblical record.

The Amphitheatre in Beit She’an. Beit She’an, a town today in the Northern District of Israel, is believed to be one of the oldest cities in the region. It has played an important role in history due to its geographical location at the junction of the Jordan River Valley and the Jezreel Valley. Beth She’an’s ancient tell contains remains beginning in the Chalcolithic period. When Canaan came under Imperial Egyptian rule in the Late Bronze Age, Beth She’an served as a major Egyptian administrative center. The Hebrew Bible identifies Beit She’an as where the bodies of King Saul and three of his sons were hung by the Philistines after the Battle of Gilboa. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Origins of the Israelites: Historical and archaeological context

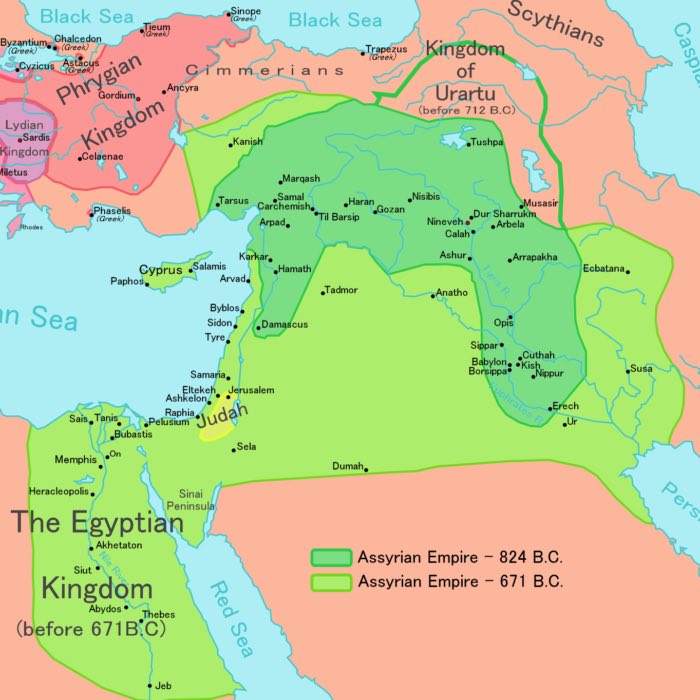

The emergence of the Israelites occurred within the broader cultural and political landscape of the Late Bronze Age collapse (circa 1200 BCE), a period characterized by the decline of major empires and the rise of smaller, decentralized societies in the Levant. This era saw the fragmentation of Canaanite city-states, creating a vacuum in which new groups, including the early Israelites, began to establish themselves.

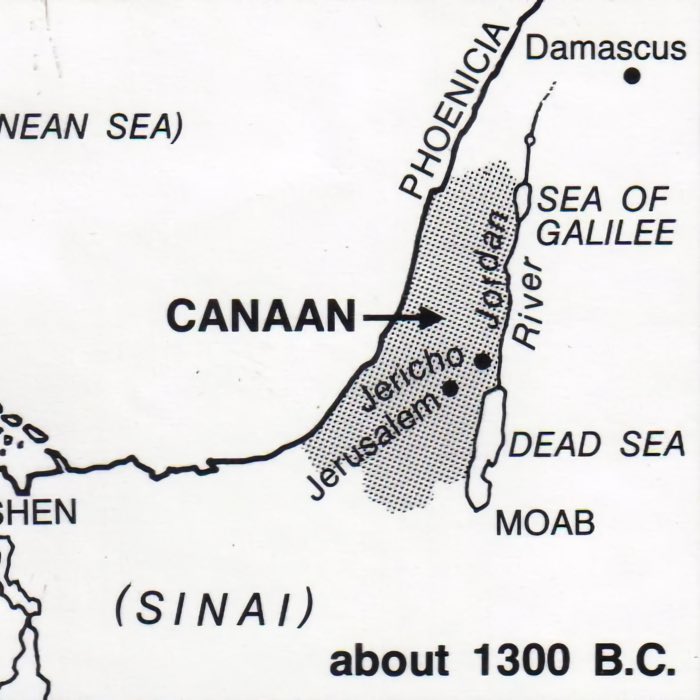

The Levant and Canaan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Levant and Canaan. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Israelites were part of a larger process of cultural and demographic change in the region, involving both continuity with and divergence from the Canaanite population. The question of their origins — whether they emerged from within Canaanite society or migrated from outside — remains a subject of scholarly debate, with archaeological data offering clues but not definitive answers.

Settlement patterns: The central highlands

One of the most significant bodies of archaeological evidence for the early Israelites comes from the central highlands of modern-day Israel and the West Bank. Surveys and excavations in this region have revealed a distinct pattern of settlement that corresponds to the biblical account of the Israelites’ establishment in the land of Canaan.

Villages and subsistence practices

Archaeological surveys have identified hundreds of small, rural settlements in the central highlands, dating to the Iron Age I period (circa 1200–1000 BCE). These settlements are characterized by modest, unfortified villages, typically consisting of a few dozen houses arranged around central courtyards. The material culture of these sites, including pottery styles and architectural features, shows continuity with Late Bronze Age Canaanite traditions but also distinct differences, such as the absence of monumental architecture and luxury goods.

The subsistence practices of these communities, as evidenced by botanical and faunal remains, suggest a focus on mixed farming and pastoralism. The use of terracing and cisterns for water management reflects an adaptation to the highland environment, supporting a sustainable, agrarian lifestyle.

Four-room houses

One of the most distinctive architectural features of early Israelite settlements is the prevalence of the so-called “four-room house.” This structure, with its characteristic layout of three parallel rooms and a central courtyard, became a hallmark of Israelite domestic architecture. While its exact origins are debated, the four-room house is often regarded as a cultural marker of Israelite identity.

A reconstructed Israelite house, 10th–7th century BCE. Eretz Israel Museum, Tel Aviv. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

A reconstructed Israelite house, 10th–7th century BCE. Eretz Israel Museum, Tel Aviv. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Model of Levantine four-roomed house from c. 900 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Model of Levantine four-roomed house from c. 900 BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Material culture and religious practices

The material culture of early Israelite settlements provides valuable insights into their social and religious practices. However, the evidence also highlights the continuity between the Israelites and their Canaanite neighbors, challenging simplistic distinctions between the two groups.

Ceramics and everyday artifacts

The pottery assemblages from early Israelite sites are utilitarian and locally produced, with simple forms and minimal decoration. These assemblages contrast with the more elaborate pottery of the Late Bronze Age Canaanite cities, reflecting the modest lifestyle of the highland settlers. Common artifacts include storage jars, cooking pots, and grinding stones, emphasizing the domestic and subsistence-oriented focus of these communities.

Potsherds and loom-weight found at archaeological sites in Israel. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC-BY-SA 4.0)

Potsherds and loom-weight found at archaeological sites in Israel. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC-BY-SA 4.0)

Cultic practices and religious identity

Archaeological evidence for religious practices in early Israelite settlements is limited but revealing. Sites such as Mount Ebal, associated by some scholars with a biblical altar, have yielded remains that suggest ritual activity, including stone installations and animal bones consistent with sacrificial practices. However, the absence of temples or monumental cultic structures in early Israelite settlements contrasts with the elaborate religious architecture of Canaanite city-states.

The Mesha Stele bears the earliest known reference (840 BCE) to the Israelite god Yahweh. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC-BY-SA 3.0)

The lack of figurative representations of deities in early Israelite contexts has been interpreted as evidence of their distinct religious identity, possibly reflecting a monolatrous or proto-monotheistic tradition centered on the worship of YHWH. However, inscriptions and artifacts from later periods, such as the Kuntillet Ajrud inscriptions referring to “YHWH and his Asherah”, indicate that early Israelite religion may have been more diverse and syncretic than traditionally assumed.

Challenges and debates in correlating archaeology and the Bible

The relationship between the archaeological record and the biblical narrative is a central and contested issue in the study of ancient Israel. While archaeological evidence provides valuable insights into the material and cultural dimensions of early Israelite society, it does not always align neatly with the historical claims of the Bible.

Archaeological excavations at Tell es-Safi/Gath, which is one of the largest pre-Classical sites in Israel, situated approximately halfway between Jerusalem and Ashkelon. The site was settled from prehistoric to modern times, and was of particular importance during the Bronze and Iron Ages, and during the Crusader period. The site is identified as Canaanite and Philistine Gath. The site is also known for its connection to the biblical story of David and Goliath. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Archaeological excavations at Tell es-Safi/Gath, which is one of the largest pre-Classical sites in Israel, situated approximately halfway between Jerusalem and Ashkelon. The site was settled from prehistoric to modern times, and was of particular importance during the Bronze and Iron Ages, and during the Crusader period. The site is identified as Canaanite and Philistine Gath. The site is also known for its connection to the biblical story of David and Goliath. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC-BY-SA 3.0)

The Exodus and conquest narratives

The biblical account of the Exodus and the conquest of Canaan by the Israelites has not been corroborated by direct archaeological evidence. Major cities mentioned in the conquest narrative, such as Jericho and Ai, show little or no evidence of destruction during the relevant period. This has led many scholars to view the biblical account as a later literary construction rather than a historical record.

Depiction of Jehu King of Israel giving tribute to the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III from Nimrud (c.827 BC). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Depiction of Jehu King of Israel giving tribute to the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III from Nimrud (c.827 BC). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Ethnogenesis and identity

Archaeological evidence supports the view that the Israelites emerged as a distinct group within the Canaanite cultural sphere rather than as foreign invaders. The concept of “ethnogenesis”, the formation of a new identity through a combination of cultural continuity and innovation, offers a useful framework for understanding this process. The adoption of unique architectural forms, settlement patterns, and religious practices likely played a role in defining early Israelite identity.

Archaeological evidence under Roman rule and from the Middle Ages

While much of the focus in Israelite archaeology centers on the Late Bronze and Iron Ages, important archaeological findings from later periods, particularly under Roman rule and during the Middle Ages, offer valuable insights into the continuity and transformation of Jewish culture and identity.

Archaeological evidence under Roman rule

The Roman Empire’s control over the region, beginning in 63 BCE, marked a significant period of transformation for Jewish society. This era saw the rise of prominent cities, monumental architecture, and the development of religious sites that reflect the complex interactions between Jewish traditions and Roman influence.

Relief on the Arch of Titus in Rome, erected at the end of the 1st century CE, showing Jewish slaves and Roman war booty from the destroyed Jerusalem Temple are brought to Rome in a triumphal procession after the conquest of Jerusalem (70 CE). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Herodian architecture and the Second Temple

One of the most striking examples of Jewish archaeology under Roman rule is the monumental expansion of the Second Temple by King Herod the Great. Herod’s ambitious building projects, including the construction of the Western Wall and the Temple Mount platform in Jerusalem, illustrate the fusion of Jewish religious tradition with Roman architectural techniques. Excavations in this area have revealed extensive remains of the temple complex, ritual baths (mikva’ot), and artifacts related to Jewish worship practices.

A small diorama/model of what the temple in Jerusalem may have looked like with the surrounding city during the time of Jesus. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

A tetradrachm minted during the Bar Kokhba revolt, featuring the former Second Temple, a lulav (palm branch), and the slogan ‘to the freedom of Jerusalem’. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Herodian palaces, such as those at Masada and Herodium, provide further evidence of the grandeur and complexity of Jewish life under Roman rule. The remains of Masada, in particular, have become emblematic of Jewish resistance during the First Jewish–Roman War (66–70 CE), with excavations uncovering fortifications, storerooms, and frescoed walls.

Synagogue remains

Archaeological evidence of synagogues from this period highlights the evolution of Jewish religious life under Roman rule. Synagogues served as centers for worship, learning, and community gatherings. Notable examples include the synagogues at Gamla, Capernaum, and Magdala, where excavations have uncovered intricately decorated mosaic floors and stone carvings, some depicting menorahs and other Jewish symbols.

Left: Dura-Europos synagogue, courtyard, western porch and prayer hall. The synagogue at Dura-Europos, a city on the Euphrates River in modern-day Syria, is one of the oldest known synagogues in the world. The building dates to the 3rd century CE and features well-preserved frescoes depicting biblical scenes and Jewish symbols. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0) – Right: Fresco of Ezra on wood panel from the Dura-Europos synagogue (3rd century CE). Ezra, a scribe and priest, is traditionally associated with the restoration of Jewish law and religious practices after the Babylonian exile. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Left: Dura-Europos synagogue, fresco showing Moses leading the Israelites across the Red Sea, a temple., ca. 244-245 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: The Torah shrine of Dura-Europos synagogue. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

Samuel anoints David, Dura Europos wall painting, Syria, 3rd century CE. The anointing of David as king is a key moment in the development of the messianic concept in Judaism. It symbolizes divine favor and appointment, establishing the Davidic dynasty as a central theme in messianic thought. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Mosaic in the Tzippori Synagogue (6th century CE). The synagogue at Tzippori (Sepphoris), located in the Galilee region, features a richly decorated mosaic floor with intricate designs. The central panel of the mosaic depicts the zodiac signs, a common motif in ancient synagogue art. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Archaeological evidence from the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages were a period of significant upheaval and change in the Levant, marked by the rise and fall of various empires and the impact of the Crusades. Despite these challenges, Jewish communities continued to thrive in certain regions, leaving behind important archaeological traces.

Medieval synagogues and Jewish quarters

Excavations in cities such as Jerusalem, Tiberias, and Safed have revealed the remains of medieval synagogues and Jewish quarters. These findings provide evidence of the architectural styles and communal life of medieval Jewish communities. For example, the remains of the ancient synagogue in Safed, a city that became a major center of Jewish mysticism (Kabbalah) in the 16th century, offer insights into the spiritual and cultural life of medieval Jewry.

Left: The Cologne Mikveh from the 8th century (rebuilt in the 11th century), rediscovered in 1956. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC-BY-SA 4.0) – Right: MiQua – LVR-Jüdisches Museum im Archäologischen Quartier Köln (former Archäologische Zone Köln), showing the progress of the excavation of the Jewish quarter in Cologne in June 2014. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC-BY-SA 4.0)

Jewish burial sites

Medieval Jewish burial sites, such as those found in the Mount of Olives cemetery in Jerusalem, contain inscriptions and artifacts that shed light on Jewish funerary practices and beliefs during this period. The tombstones often bear Hebrew inscriptions and symbols, providing valuable information about the individuals buried there and the communities they belonged to.

Conclusion

The archaeological evidence for the Israelites provides a rich and nuanced picture of their origins and early development, revealing both their connections to the Canaanite world and their distinct cultural and religious identity. While the archaeological record does not fully align with the biblical narrative, it offers valuable insights into the historical context in which these texts were written and the complex processes that shaped the Israelite people.

References and further reading

- Dever, W. G., What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? Archaeology and the Construction of Ancient Israel, 2001, Eerdmans, ISBN: 978-0802821263

- Finkelstein, I., & Silberman, N. A., The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, 2002, Free Press, ISBN: 978-0684869131

- Faust, A., The Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement, 1988, Israel Exploration Society, ISBN: 978-9652210074

- Levy, T. E. (Ed.), The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land, 1998, Leicester University Press, ISBN: 978-0826469960

- Hershel Shanks, The Rise Of Ancient Israel, 1992, Biblical Archaeology Society, ISBN: 9781880317075

- Amihay Mazar, Ephraim Stern, Archaeology Of The Land Of The Bible - 10,000-586 B.C.E, 1992, Yale University Press, ISBN: 9780300140071

- Steven Fine, Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman world - Toward a new Jewish archaeology, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 9780521145671

- George Ernest Wright, Biblical Archaeology, 1960, Verlag n/a, ISBN: 9780664243067

- Richard S. Hess, Israelite Religions - An Archaeological And Biblical Survey, 2007, Baker Academic, ISBN: 9780801027178

- William G. Dever, Beyond The Texts - An Archaeological Portrait Of Ancient Israel And Judah, 2020, SBL Press, ISBN: 9780884144915

comments