Essential terms and concepts in Greek philosophy and their thinkers

Greek philosophy offers a treasure trove of concepts and ideas that have profoundly influenced the intellectual traditions of the Western world. Many of these terms encapsulate complex philosophical systems, debates, and insights, often tied to specific thinkers or schools. I thought, it would be useful to have a reference guide to some of the essential terms and concepts in Greek philosophy and the philosophers associated with them. This list is by no means exhaustive but aims to provide a starting point for exploring classical Greek thought.

Adiaphora

In classical ¢Greek philosophy](/weekend_stories/told/2025/2025-01-03-greek_philosophy/), adiaphora (ἀδιάφορα) refers to things that are “indifferent” or “neutral” in moral and philosophical terms. These are matters or actions considered neither inherently good nor bad, and thus, they do not directly contribute to or detract from the attainment of a virtuous life or eudaimonia (human flourishing).

The concept of adiaphora was developed primarily in the context of Hellenistic philosophies, particularly by the Stoics, but it also appears in the works of earlier thinkers.

Key philosophers:

- Zeno of Citium: The founder of Stoicism, who laid the groundwork for the Stoic ethical framework, including the classification of adiaphora.

- Epictetus: A later Stoic philosopher who emphasized the distinction between what is within our control (virtue) and what is not (adiaphora).

- Sextus Empiricus: A prominent Skeptic who discussed the role of adiaphora in achieving ataraxia through suspension of judgment.

Stoicism

The Stoics elaborated the idea of adiaphora extensively within their ethical framework. According to Stoic doctrine, the ultimate goal of life is to live in accordance with nature, which entails living a life of virtue. Virtue alone is considered the highest good (summum bonum), while vice is the only true evil. Everything else—such as health, wealth, pleasure, pain, and external possessions—is categorized as adiaphora because these things are neither good nor bad in themselves.

However, the Stoics introduced a further subdivision within adiaphora:

- Preferred indifferents (προηγμένα): These are things that are naturally desirable, such as health, wealth, and education. While not constituting true goods, they are to be “preferred” as they align with nature and facilitate virtuous living.

- Dispreferred indifferents (ἀποπροηγμένα): These are things naturally undesirable, such as illness, poverty, or pain, but they do not prevent one from living a virtuous life.

This distinction underscores the Stoic emphasis on inner virtue as the only determinant of happiness, with external circumstances relegated to a secondary, neutral status.

Skepticism

The Skeptics, particularly those in the Pyrrhonian tradition, also employed the concept of adiaphora but in a different manner. For the Skeptics, adiaphora reflects their suspension of judgment (epoché). Since Skeptics refrain from making definitive claims about what is good or bad, they treat all external matters as indifferent, thereby achieving a state of mental tranquility (ataraxia).

Epicureanism

While the Epicureans did not use the term adiaphora as systematically as the Stoics or Skeptics, they also implicitly addressed the idea of indifference. Epicurus distinguished between natural and necessary desires, natural but unnecessary desires, and vain desires. The latter category, such as excessive wealth or fame, could be seen as parallel to adiaphora, as these things do not contribute to true happiness.

Historical development and influence

The notion of adiaphora gained further significance in early Christian thought, particularly in theological and ethical discussions. Christian writers like the self-proclaimed “apostle” Paul adapted the term to denote matters that are morally neutral and do not affect one’s salvation, such as dietary choices or observing specific holy days (e.g., Romans 14). Later, during the Reformation, the concept was revived in debates over adiaphoristic controversies, concerning which church practices were essential or indifferent to faith.

Agathon

Agathon (ἀγαθόν) refers to “the good” in classical Greek philosophy. It represents the ultimate ideal or purpose of human life and action, embodying the highest value and serving as a central focus in ethics, metaphysics, and theology.

Key philosophers:

- PlatoPlato: Developed the concept of the Form of the Good as the ultimate reality and source of all knowledge.

- Aristotle: Interpreted agathon as the practical and achievable goal of human life, grounded in virtue and reason.

- Zeno of Citium: Stoic founder who emphasized virtue as the sole intrinsic good.

- Epicurus: Reinterpreted agathon in terms of hedonistic tranquility.

- Plotinus: Identified agathon with the One, the source of all existence in Neoplatonic thought.

Plato

In Platonic philosophy, agathon is a cornerstone of his metaphysical system. Plato describes the Form of the Good (to agathon) as the highest and most transcendent of all Forms, the source of truth, beauty, and being. In the Republic, Socrates compares the Good to the sun, which illuminates and enables knowledge and existence. The Form of the Good is what gives intelligibility to all other Forms and represents the ultimate goal of philosophical inquiry and virtuous living.

Plato’s idea of agathon is inherently abstract and absolute, emphasizing that the Good is beyond direct comprehension but is the source of all reality and knowledge.

Aristotle

Aristotle approaches agathon differently, grounding it in practical and teleological contexts. In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle identifies the highest good with eudaimonia (flourishing or happiness), which is achieved through virtuous activity in accordance with reason. For Aristotle, agathon is not an abstract Form but the end (telos) that all human actions aim to achieve.

Aristotle’s ethics and metaphysics emphasize a more practical understanding of the Good, closely tied to human nature and the function (ergon) of a rational being.

Stoicism

The Stoics regard agathon as synonymous with virtue, which they see as the only true good. External factors such as wealth, health, and pleasure are categorized as “indifferents” (adiaphora) because they do not contribute to or detract from virtue. For the Stoics, living in harmony with nature and reason is the path to achieving the Good.

Epicureanism

Epicureans redefine agathon in terms of pleasure (hedone), specifically the absence of pain and disturbance. For Epicurus, the Good is a life of tranquility and self-sufficiency, achieved by satisfying natural and necessary desires while avoiding unnecessary or harmful ones.

Neoplatonism

In Neoplatonism, agathon is equated with the One, the ultimate principle of reality from which all existence emanates. Plotinus describes the Good as the ineffable source of unity and being, transcending all categories of thought and existence. The journey toward agathon involves the soul’s ascent through contemplation and self-purification.

Historical development and influence

The concept of agathon has profoundly influenced Western philosophy, shaping ethical, metaphysical, and theological discussions. It remains central to debates about the nature of value, purpose, and the ultimate aims of human life.

Aitia

Aitia (αἰτία) translates as “cause” or “reason” and is a foundational concept in Greek philosophy, particularly in discussions of metaphysics, epistemology, and natural science. It refers to the principles or explanations that account for why things are the way they are.

Key philosophers:

- Aristotle: His four causes remain a cornerstone in understanding causation.

- Plato: His metaphysical interpretation of ultimate and secondary causes.

- Pre-Socratics: Their exploration of natural principles as explanatory causes.

Aristotle

Aristotle’s treatment of aitia is perhaps the most systematic and influential. In his work Physics and Metaphysics, Aristotle identifies four types of causes that provide a comprehensive framework for understanding change and existence:

- Material Cause (ὑλική αἰτία): The substance or matter out of which something is made. For example, the marble of a statue.

- Formal Cause (εἶδος): The form or essence that defines what a thing is. For the statue, it is the design or pattern it follows.

- Efficient Cause (κινοῦν): The agent or process that brings something into being. For the statue, it is the sculptor’s work.

- Final Cause (τέλος): The purpose or end for which something exists. For the statue, it could be to honor a deity or decorate a space.

This framework has profoundly influenced subsequent philosophical and scientific inquiry by emphasizing a holistic understanding of causation.

Plato

While Plato does not systematize causes as Aristotle does, he discusses causation extensively, especially in the Timaeus and the Phaedo. For Plato, the ultimate aitia is the Form of the Good, which is the source of order and purpose in the cosmos. Secondary causes, such as the Demiurge in the Timaeus, function as intermediaries that shape the material world according to the patterns of the Forms.

Pre-Socratic Thought

The concept of aitia can be traced back to early Greek thinkers who sought natural explanations for the cosmos. For example:

- Thales attributed causes to natural elements like water.

- Anaximander proposed the apeiron (the infinite) as the origin and principle of all things.

- Heraclitus emphasized the role of change and logos as fundamental causes.

Stoicism

In Stoic philosophy, aitia is closely tied to the concept of logos, the rational principle governing the universe. The Stoics view causation as deterministic, where every event has a cause rooted in the rational order of nature.

Akatalepsia

Akatalepsia (ἀκαταληψία) translates to “incomprehensibility” or “incapability of being grasped”. It is a concept central to Skeptic philosophy, particularly in its Pyrrhonian and Academic forms, and it signifies the belief that human beings cannot attain certain knowledge about the nature of things.

Key philosophers:

- Sextus Empiricus: A prominent Pyrrhonian Skeptic who extensively articulated the role of akatalepsia in achieving tranquility.

- Arcesilaus: An Academic Skeptic who emphasized the impossibility of certain knowledge and promoted probabilistic reasoning.

- Carneades: Developed the Academic Skeptic stance further, refining the idea of using plausible beliefs as guides for action without claiming certainty.

Pyrrhonian skepticism

In Pyrrhonian skepticism, akatalepsia represents the acknowledgment that absolute certainty is unattainable. This view leads Skeptics to suspend judgment (epoché) on all matters, avoiding assertions about what is true or false. According to Sextus Empiricus, by maintaining a stance of akatalepsia, Skeptics achieve mental tranquility (ataraxia), as they are no longer disturbed by the search for definitive answers or the fear of being wrong.

Academic skepticism

The concept of akatalepsia was also a cornerstone of the Academic Skeptics, particularly during the era of Arcesilaus and Carneades. They argued that since nothing can be known with absolute certainty, the wise person should rely on probabilities rather than definitive claims. This probabilistic approach allowed them to navigate practical life while maintaining intellectual humility.

Contrast with Stoicism

The Stoics directly opposed the idea of akatalepsia. They argued that some perceptions, which they called kataleptic impressions (phantasiai katalēptikai), are self-evident and bear the mark of truth. For the Stoics, such impressions serve as the foundation for certain knowledge. The dispute between the Stoics and Skeptics over the possibility of katalepsis (certain knowledge) was a significant philosophical debate in antiquity.

Historical development and influence

The concept of akatalepsia influenced later philosophical and theological traditions, including debates about the limits of human reason in early Christian and medieval thought. Its emphasis on intellectual humility and the suspension of judgment continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about epistemology and the nature of belief.

Aklineis

Aklineis (ἀκλινής) refers to a state of being “unwavering” or “unshaken”. It is a term used to describe a philosophical disposition or mental attitude characterized by steadfastness, stability, and resistance to external disturbances or internal doubt. ** **Key philosophers:

- Epictetus: Emphasized unwavering control over one’s internal state, maintaining a resolute adherence to Stoic principles.

- Sextus Empiricus: His works illustrate the Skeptic’s commitment to mental stability through non-attachment to absolute truths.

Stoicism

The term aligns closely with Stoic ideals of resilience and inner tranquility. For the Stoics, aklineis reflects the sage’s unshaken adherence to reason and virtue, regardless of external circumstances. This steadfastness is seen as essential for achieving ataraxia (peace of mind) and living in accordance with nature. A Stoic sage remains aklineis in the face of adversity, guided by the conviction that external events are beyond one’s control and thus indifferent (adiaphora).

Skepticism

In Pyrrhonian skepticism, aklineis is associated with the ideal mental state resulting from suspension of judgment (epoché). By avoiding dogmatic commitments, the Skeptic achieves freedom from doubt and disturbance, embodying an unwavering equanimity in the face of competing claims about truth.

Epicureanism

Although the term is not explicitly used by the Epicureans, the concept of mental steadfastness resonates with their ideal of a tranquil mind (ataraxia). For Epicurus, aklineis would be the unwavering focus on avoiding pain and fear, achieved through philosophical reflection and the cultivation of simple pleasures.

Akradantous

Akradantous (ἀκραδάντους) translates to “unshakable” or “unwavering”. It describes a state of steadfastness and resolute firmness, particularly in one’s beliefs, convictions, or character. The term is often associated with philosophical ideals of inner strength and immutability in the face of external challenges or internal doubts.

Key philosophers:

- Epictetus: His teachings often emphasize the importance of remaining resolute and unshaken in the face of adversity by focusing only on what is within one’s control.

- Sextus Empiricus: Advocated for mental steadiness through the suspension of judgment, allowing for a life free of turmoil.

- Epicurus: Though not directly using the term, his advocacy for a tranquil and fearless life resonates with the concept of unshakable resolve.

Stoicism

In Stoic philosophy, akradantous aligns with the ideal of the sage, who remains unshaken by external circumstances or emotional turbulence. For the Stoics, an unshakable character is achieved through the cultivation of virtue and rationality, enabling the individual to maintain equanimity regardless of external events. This steadfastness is essential for achieving ataraxia (tranquility) and living in harmony with nature.

Skepticism

While Skeptics emphasize the suspension of judgment (epoché), akradantous can be seen as a byproduct of their philosophy. By refusing to commit to absolute truths, Skeptics achieve a kind of unwavering mental state, free from the disturbances caused by dogmatic beliefs. Sextus Empiricus highlights this stability as a pathway to ataraxia, as it eliminates the inner conflicts associated with certainty and doubt.

Epicureanism

Although not explicitly using the term akradantous, Epicurean philosophy values a steady and unshaken mind as a component of a tranquil life. For Epicurus, freedom from fear and disturbance (ataraxia) is achieved by focusing on simple pleasures and avoiding unnecessary desires or fears, particularly those rooted in superstition or fear of death.

Historical development and influence

The concept of akradantous reflects enduring ideals of resilience and steadfastness, influencing subsequent philosophical and ethical systems. It remains a central theme in discussions of character, virtue, and the philosophical pursuit of inner stability.

Aletheia

Aletheia (ἀλήθεια) translates to “truth” or “unconcealment” in classical Greek. It represents a central concept in Greek philosophy, emphasizing the nature of reality as it is revealed and understood. Unlike the modern notion of truth as correspondence, aletheia often carries a sense of disclosure or bringing forth what is hidden.

Key philosophers:

- Heraclitus: Emphasized truth as the understanding of the dynamic and unified nature of the cosmos.

- Parmenides: Distinguished aletheia as the path of reason and being, opposed to the deceptive realm of opinion.

- Plato: Connected aletheia to the intellectual apprehension of the eternal Forms.

- Aristotle: Defined truth as correspondence, but also explored its role in uncovering reality’s principles.

- Stoics: Saw truth as living in accordance with nature and reason, accessible through clear perceptions.

Pre-Socratic philosophy

The concept of aletheia is prominent in early Greek thought. Heraclitus, for instance, viewed truth as the understanding of the underlying unity and change of the cosmos, revealed through the logos. Parmenides also explored aletheia in his poem, contrasting it with “opinion” (doxa), which he considered deceptive and tied to sensory perception. For Parmenides, aletheia reflects the eternal and unchanging nature of being.

Plato

In Platonic philosophy, aletheia is tied to the realm of the Forms. For Plato, truth is apprehended through intellectual insight rather than sensory experience. The allegory of the cave in the Republic illustrates this: aletheia is the light of the sun that illuminates the true reality outside the cave, contrasted with the shadows of illusion. Truth, in this sense, is a process of uncovering and ascending toward knowledge of the Good.

Aristotle

Aristotle adopted a more practical and systematic approach to aletheia. For him, truth is the correspondence between thought and reality: “To say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true”. While this definition aligns more closely with modern notions of truth, Aristotle’s exploration of aletheia also extends into metaphysics, where the pursuit of knowledge involves uncovering the principles and causes of things.

Stoicism

The Stoics regarded aletheia as an alignment with reason and nature. Truth was accessible through kataleptic impressions (“clear and distinct perceptions”) that reliably correspond to reality. Living according to aletheia meant aligning one’s life with the rational order of the cosmos.

Heidegger (modern engagement):

While not part of classical Greek thought, Martin Heidegger’s reinterpretation of aletheia as “unconcealment” brings renewed focus to its original Greek sense. Heidegger contrasts aletheia with the modern emphasis on truth as mere accuracy, emphasizing instead the process by which beings are revealed in their fullness.

Historical development and influence

The concept of aletheia has profoundly shaped Western thought, influencing discussions about the nature of reality, knowledge, and the human condition. Its emphasis on uncovering and revealing resonates in philosophical, theological, and scientific traditions.

Amatha

Amatha (ἄμαθα) translates to “ignorance” or “lack of learning” in classical Greek. It denotes not merely the absence of knowledge but a more profound inability or unwillingness to engage with truth, reason, or ethical understanding. In philosophical discourse, amatha is often contrasted with wisdom (sophia) or learning (paideia).

Key philosophers:

- Heraclitus: Critiqued ignorance as blindness to the logos and the dynamic nature of the cosmos.

- Plato: Explored amatha as a fundamental obstacle to justice, knowledge, and the good life, depicting it vividly in the allegory of the cave.

- Aristotle: Addressed ignorance in the context of moral error and the necessity of practical wisdom.

- Epictetus: Tied ignorance to irrationality and emphasized the importance of philosophical education in overcoming it.

Pre-Socratic philosophy

In early Greek thought, amatha was often associated with the failure to understand the natural order or the principles governing the cosmos. Heraclitus, for example, criticized those who failed to grasp the logos, the underlying rational principle of the universe, as living in a state of amatha. He saw ignorance as a barrier to living in harmony with nature.

Plato

Plato frequently addresses amatha in his dialogues, contrasting it with the pursuit of wisdom and virtue. In works such as the Republic, ignorance is depicted as the root of injustice and disorder, both in the soul and in society. The allegory of the cave vividly illustrates amatha as a state of being trapped in illusions, mistaking shadows for reality. For Plato, overcoming amatha requires education (paideia) and the ascent toward knowledge of the Forms, culminating in the understanding of the Good (to agathon).

Aristotle

While Aristotle does not use the term amatha as extensively as Plato, he addresses the concept in his discussions of intellectual and moral virtues. Ignorance, for Aristotle, can be either culpable or non-culpable, depending on whether it results from a lack of effort or unavoidable circumstances. In the Nicomachean Ethics, he links ignorance to moral error, emphasizing the importance of practical wisdom (phronesis) in making virtuous decisions.

Stoicism

The Stoics view amatha as a failure to live in accordance with reason and nature. For Stoic philosophers such as Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, ignorance is the source of irrational desires, fears, and emotional disturbances. Overcoming amatha involves cultivating an understanding of the natural order and aligning one’s actions with the rational principles of the cosmos.

Skepticism

While Skeptics do not explicitly use the term amatha, their philosophy implicitly acknowledges it by highlighting the limits of human knowledge. By practicing suspension of judgment (epoché), Skeptics aim to avoid the dogmatism that they associate with ignorance, thus achieving a state of tranquility (ataraxia).

Historical development and influence

The concept of amatha has remained a cornerstone in philosophical discussions about the nature of knowledge, ethical responsibility, and human flourishing. Its role as a counterpoint to wisdom continues to inform debates about education, morality, and the human condition.

Anamnesis

Anamnesis (ἀνάμνησις) translates to “recollection” or “remembrance” in classical Greek philosophy. It refers to the process of recalling knowledge or truths that are innate to the soul but forgotten due to its embodied existence. This concept is most famously associated with Plato, who uses it to explain the acquisition of knowledge as a process of remembering rather than learning afresh.

Key philosophers:

- Plato: Developed the concept of anamnesis as the foundation of his theory of knowledge and the soul’s immortality.

- Plotinus: Integrated anamnesis into Neoplatonic mysticism, emphasizing spiritual ascent and unity with the One.

- Aristotle: While critical of Platonic anamnesis, he contributed to discussions of memory and learning as natural processes tied to sensory experience.

Plato

In Platonic philosophy, anamnesis is central to his epistemology and metaphysics, particularly as expressed in dialogues such as the Meno and Phaedo. Plato posits that the soul is immortal and has encountered the Forms—eternal, unchanging truths—prior to its incarnation in the physical body. According to this view, learning is not the acquisition of new information but the recollection of these pre-existing truths. For instance, in the Meno, Socrates demonstrates anamnesis by guiding a slave boy to “remember” geometric principles he had not been explicitly taught, thereby illustrating the soul’s inherent knowledge.

Aristotle

Aristotle diverges significantly from Plato on the concept of anamnesis. While he acknowledges the role of memory and recollection in human cognition, he grounds these processes in empirical experience rather than innate knowledge. For Aristotle, knowledge arises from sensory experience and intellectual abstraction, not from the recollection of pre-existing truths.

Stoicism

Though Stoicism does not explicitly adopt anamnesis, its focus on aligning with the rational order of the cosmos resonates with the Platonic idea that truth is not created but discovered. Stoics emphasize the importance of reason as a tool for recognizing universal truths inherent in nature and the self.

Neoplatonism

Plotinus and later Neoplatonists expand on Plato’s idea of anamnesis. For them, recollection becomes a spiritual process of returning to the One, the ultimate source of all being. This ascent involves purifying the soul and stripping away the distractions of the material world to remember its divine origin and unity with the One.

Historical development and influence

The idea of anamnesis profoundly influenced later philosophical and theological traditions. Early Christian thinkers such as Augustine adapted the concept to describe the soul’s longing for God and the recovery of divine truths through introspection and grace. The theme of recollection continues to inspire modern philosophical inquiries into the nature of knowledge, memory, and the human condition.

Anepikrita

Anepikrita (ἀνεπίκριτα) translates to “unresolved” or “undecided” in classical Greek. It signifies questions or matters that remain open, lacking definitive answers or conclusions. The term is often used in philosophical discussions to describe states of intellectual uncertainty or issues that resist final judgment.

Key philosophers:

- Sextus Empiricus: Emphasized anepikrita as central to Skeptic philosophy, highlighting the benefits of suspending judgment.

- Arcesilaus: Advocated for the Academic Skeptic approach of withholding assent on unresolved issues.

- Carneades: Developed the idea of relying on probabilities while acknowledging the limits of certainty.

- Chrysippus: Countered the concept of anepikrita by defending the Stoic claim to certain knowledge through reason and clear impressions.

Skepticism

In the Pyrrhonian Skeptic tradition, anepikrita captures the essence of their epistemological stance. Skeptics maintain that many questions about the nature of reality are inherently undecidable due to the equal weight of opposing arguments. By suspending judgment (epoché), Skeptics accept the unresolved nature of these issues, leading to a state of mental tranquility (ataraxia). Sextus Empiricus, a key figure in Skepticism, frequently emphasizes the value of acknowledging anepikrita as part of the philosophical journey.

Academic skepticism

The Academic Skeptics, particularly during the time of Arcesilaus and Carneades, also engaged with anepikrita. They argued that since certainty is unattainable, it is rational to withhold assent on undecidable issues. Instead, they advocated for relying on probabilities to guide practical action, while still recognizing the unresolved nature of ultimate truths.

Stoicism

While the Stoics opposed the Skeptical embrace of anepikrita, they addressed the concept indirectly in their defense of kataleptic impressions (“clear and distinct perceptions”). For the Stoics, these impressions serve as the basis for certain knowledge, resolving questions that Skeptics might deem anepikrita. The Stoics argued that reason enables humans to achieve clarity and certainty, countering the unresolved stance of their Skeptical counterparts.

Neoplatonism

In Neoplatonism, unresolved questions (anepikrita) are seen as part of the soul’s ascent toward higher knowledge. Plotinus acknowledges that some matters may remain undecided at lower levels of understanding, but through contemplation and spiritual purification, the soul can transcend intellectual uncertainty and approach unity with the One, where all apparent contradictions dissolve.

Historical development and influence

The idea of anepikrita has had a lasting impact on philosophical discussions about doubt, inquiry, and the limits of human knowledge. It continues to inform contemporary debates in epistemology, particularly in contexts where certainty is unattainable, and open-ended exploration is valued.

Aphasia

Aphasia (ἀφασία) translates to “speechlessness” or “inability to speak” in classical Greek. In philosophical contexts, it denotes a deliberate silence or refusal to make definitive assertions about the nature of reality. The term is closely associated with the practice of suspending judgment (epoché) in Skeptic philosophy, reflecting a state of mental tranquility and freedom from dogmatic belief.

Key philosophers:

- Sextus Empiricus: A leading advocate of aphasia as a means to achieve tranquility and avoid dogmatic errors.

- Arcesilaus: While not fully endorsing aphasia, he emphasized the limits of certainty in Academic skepticism.

- Chrysippus: A Stoic critic of aphasia, defending the possibility of clear and rational knowledge.

Pyrrhonian skepticism

In Pyrrhonian skepticism, aphasia is a cornerstone of the philosophical method. By refraining from asserting anything as true or false, Skeptics maintain a neutral stance toward competing claims. Sextus Empiricus describes aphasia as the natural outcome of the Skeptic’s suspension of judgment. This silence is not ignorance but a conscious strategy to avoid the disturbances caused by dogmatic assertions, thereby achieving mental peace (ataraxia).

Academic skepticism

While the Academic Skeptics also emphasized doubt and uncertainty, they did not advocate for complete aphasia. Philosophers like Arcesilaus and Carneades used arguments to challenge dogmatic positions, but they engaged in probabilistic reasoning to guide practical decisions. Thus, aphasia in its strictest sense was more characteristic of Pyrrhonian skepticism.

Stoicism

Stoic philosophy opposed aphasia, viewing it as an abdication of reason and the pursuit of truth. The Stoics argued that certain knowledge could be achieved through kataleptic impressions (“clear and distinct perceptions”). For them, the refusal to assert truths undermined the rational capacity of humans to align with the natural order.

Historical development and influence

The concept of aphasia influenced later philosophical and theological traditions, particularly in discussions about the limits of human understanding. It remains a significant theme in epistemology, highlighting the tension between doubt, assertion, and the quest for certainty.

Aporia

Aporia (ἀπορία) translates to “perplexity” or “impasse” in classical Greek. It describes a state of puzzlement or uncertainty that arises when one encounters a question or problem for which no clear solution or answer is immediately available. In philosophy, aporia is both a methodological tool and a critical moment in inquiry, often marking the starting point for deeper reflection and understanding.

Key philosophers:

- Socrates: Master of using aporia to challenge assumptions and stimulate philosophical inquiry.

- Plato: Explored aporia as a means to provoke deeper examination of ethical and metaphysical concepts.

- Aristotle: Systematically analyzed aporiai to advance the study of metaphysics and natural philosophy.

- Sextus Empiricus: Highlighted aporia as a central feature of Skeptic practice, leading to tranquility.

Socratic philosophy

In the dialogues of Plato, Socrates frequently employs aporia as a method to expose the inadequacies of his interlocutors’ assumptions. By leading them to a state of perplexity through rigorous questioning, Socrates encourages a recognition of ignorance, which he views as the first step toward genuine knowledge. For example, in the Meno, the dialogue culminates in an aporetic state about the nature of virtue, prompting the exploration of new avenues of thought.

Aristotelian thought

Aristotle uses aporia differently, treating it as a systematic tool for identifying and addressing philosophical problems. In his Metaphysics, Aristotle introduces aporiai (plural of aporia) as difficulties or contradictions that arise when examining fundamental questions, such as the nature of being or the causes of change. Resolving these aporiai is central to advancing philosophical understanding.

Skepticism

For Skeptics, aporia signifies the suspension of judgment (epoché) that results from encountering equally compelling arguments on opposing sides of an issue. Sextus Empiricus frames this state as a pathway to ataraxia (tranquility), as the absence of definitive conclusions frees one from the anxiety of dogmatic commitment.

Stoicism

While Stoic philosophy does not embrace aporia as a method, it acknowledges moments of perplexity in the journey toward wisdom. Stoics emphasize the importance of using reason and virtue to navigate and resolve such impasses, aligning one’s understanding with the natural order of the cosmos.

Historical development and influence

The concept of aporia has remained a vital tool in philosophical and critical inquiry, influencing methodologies in epistemology, ethics, and metaphysics. Its emphasis on questioning and the recognition of uncertainty continues to resonate in contemporary philosophical debates and education.

Arete

Arete (ἀρετή) translates to “excellence” or “virtue” in classical Greek. It signifies the highest quality or fulfillment of purpose that an individual or object can achieve. In philosophical and ethical contexts, arete refers to the cultivation of moral and intellectual virtues, embodying the ideal of living in accordance with one’s highest potential.

Key philosophers:

- Homer: Introduced the concept of arete as excellence in action, particularly in heroic contexts.

- Socrates: Reframed arete as intellectual and moral virtue, rooted in knowledge and the pursuit of the Good.

- Plato: Explored arete as the harmonious development of virtues essential to individual and societal well-being.

- Aristotle: Systematized arete within his ethical framework, emphasizing its role in achieving eudaimonia.

- Zeno of Citium: Emphasized arete as the Stoic ideal of living virtuously in alignment with nature.

Homeric tradition

In early Greek thought, particularly in Homer’s epics, arete is associated with physical prowess, bravery, and honor in battle. It reflects the qualities that define a hero, such as Achilles or Odysseus, in achieving greatness and recognition through their deeds. This understanding of arete emphasizes excellence within a specific context, such as warfare or leadership.

Socratic philosophy

Socrates redefines arete as a moral and intellectual virtue rather than external achievements. In dialogues such as the Meno and Apology, Socrates argues that arete is tied to knowledge and wisdom, as true excellence requires understanding what is good and just. He emphasizes the inseparability of virtue from knowledge, proposing that ignorance is the root of moral failure.

Plato

In Plato’s philosophy, arete encompasses the virtues necessary for achieving the harmonious functioning of the soul and society. In the Republic, the cardinal virtues—wisdom, courage, moderation, and justice—are the expressions of arete. Plato also connects arete to the idea of the Good (to agathon), suggesting that true excellence involves aligning oneself with the ultimate reality of the Forms.

Aristotle

For Aristotle, arete is central to his ethical system as outlined in the Nicomachean Ethics. He defines arete as a habitual disposition to act in accordance with reason and the mean between extremes of excess and deficiency. Moral virtues such as courage, temperance, and justice are examples of arete that lead to eudaimonia (flourishing or happiness). Intellectual virtues, such as wisdom (sophia) and practical reason (phronesis), are also integral to achieving the highest form of human excellence.

Stoicism

In Stoic philosophy, arete is synonymous with living in accordance with nature and reason. The Stoics emphasize that virtue is the only true good and is sufficient for achieving a fulfilling life. For them, arete involves the development of rationality, self-control, and alignment with the cosmic order.

Epicureanism

Although the Epicureans focus on pleasure (hedone) as the highest good, they recognize virtues such as prudence and moderation as instrumental to achieving tranquility and freedom from pain. In this sense, arete serves as a practical guide rather than an intrinsic end.

Historical development and influence

The concept of arete has shaped ethical thought throughout history, influencing not only Greek philosophy but also Roman, medieval, and modern ethical systems. Its emphasis on excellence and virtue continues to inspire discussions about the nature of human potential, character development, and the good life.

Astathmēta

Astathmēta (ἀστάθμητα) translates to “unmeasured”, “unpredictable”, or “unstable” in classical Greek. It describes phenomena or situations that resist precise quantification or control, often evoking a sense of unpredictability or uncertainty. In philosophical contexts, the term is used to reflect the inherent complexity and variability of life, nature, or human affairs.

Key philosophers:

- Heraclitus: Emphasized the flux and instability of existence, highlighting the astathmēta character of the cosmos.

- Plato: Contrasted the instability of the material world with the unchanging stability of the Forms.

- Aristotle: Explored the role of prudence in navigating life’s unpredictability.

- Epictetus: Advocated for inner stability and virtue as responses to the unpredictable nature of external events.

- Sextus Empiricus: Addressed the variability of appearances and the suspension of judgment as a response to astathmēta.

Pre-Socratic philosophy

The concept of astathmēta aligns with the pre-Socratic focus on the flux and instability of the cosmos. Heraclitus, for instance, emphasized the constant change and unpredictability of the universe, encapsulated in his statement that “you cannot step into the same river twice”. This idea underscores the astathmēta nature of existence as a dynamic and ever-shifting reality.

Plato

In Platonic thought, astathmēta is often contrasted with the stability and perfection of the Forms. While the material world is marked by instability and imperfection, the realm of the Forms represents unchanging truth and order. Plato’s philosophy suggests that understanding and transcending the astathmēta aspects of the physical world is essential for attaining knowledge and aligning with the Good.

Aristotle

Aristotle acknowledges the unpredictable nature of certain aspects of life, particularly in his discussions of chance (tyche) and contingency. In the Nicomachean Ethics, he highlights the role of prudence (phronesis) in navigating the astathmēta elements of human life, emphasizing the importance of practical wisdom in making decisions amid uncertainty.

Stoicism

Stoic philosophy embraces the astathmēta of external events as part of the natural order. The Stoics teach that while external circumstances are often unpredictable and beyond human control, individuals can maintain inner stability by focusing on their own rationality and virtue. The concept of astathmēta thus reinforces the Stoic distinction between what is within our control and what is not.

Skepticism

For the Skeptics, astathmēta reflects the limitations of human knowledge and the variability of appearances. The acknowledgment of instability in perceptions and judgments leads to the suspension of belief (epoché), fostering a sense of tranquility (ataraxia) amidst the unpredictable nature of life.

Historical development and influence

The concept of astathmēta has influenced philosophical approaches to uncertainty, change, and the limits of human control. Its emphasis on unpredictability continues to resonate in discussions of ethics, epistemology, and the philosophy of science, where variability and instability remain central challenges to understanding and action.

Ataraxia

Ataraxia (ἀταραξία) translates to “tranquility” or “freedom from disturbance” in classical Greek. It represents a state of inner calm and unshakable peace, achieved through the absence of mental agitation and emotional turmoil. In philosophical contexts, ataraxia is often portrayed as the ultimate goal of life, a state where one is undisturbed by external events or internal anxieties.

Key philosophers:

- Sextus Empiricus: Described ataraxia as the outcome of Skeptic practices, emphasizing suspension of judgment.

- Epicurus: Linked ataraxia to the elimination of fear and the pursuit of simple pleasures.

- Epictetus: Advocated for inner peace through the Stoic discipline of focusing on what is within one’s control.

- Democritus: Highlighted the importance of balance and moderation in achieving a cheerful and tranquil life.

Skepticism

Ataraxia is a central concept in Pyrrhonian skepticism, where it arises as a result of suspending judgment (epoché) about the nature of reality. Sextus Empiricus argues that by refraining from making definitive claims about what is true or false, individuals can avoid the mental disturbances caused by dogmatic beliefs. This suspension leads to a state of ataraxia, characterized by a serene acceptance of life’s uncertainties.

Epicureanism

In Epicurean philosophy, ataraxia is achieved through the absence of fear, particularly the fear of gods and death. Epicurus teaches that by understanding the natural causes of phenomena and recognizing the finality of death, individuals can free themselves from irrational fears. Ataraxia in this context is paired with physical pleasure (aponia), creating a life of balance and contentment.

Stoicism

While the term ataraxia is not central to Stoic philosophy, its essence is reflected in the Stoic ideal of maintaining equanimity regardless of external circumstances. For the Stoics, inner peace is achieved by focusing on what is within one’s control (virtue and rationality) and accepting what is not (external events) as part of the natural order. This perspective aligns with the practical attainment of tranquility in the face of life’s challenges.

Pre-Socratic philosophy

Although not explicitly named, the notion of ataraxia can be seen in the teachings of Democritus, who advocates for moderation and the cultivation of cheerfulness (euthymia). His view emphasizes the importance of inner harmony and freedom from excessive desires or fears as keys to a tranquil life.

Historical development and influence

The concept of ataraxia has profoundly influenced philosophical and ethical thought, shaping approaches to mental well-being and resilience. Its emphasis on inner tranquility continues to inspire modern discussions in philosophy, psychology, and mindfulness practices.

Autarkeia

Autarkeia (αὐτάρκεια), meaning “self-sufficiency” or “independence”, is a central concept in ancient Greek philosophy, particularly in ethical and political contexts. It refers to the state of being complete and self-contained, requiring nothing external to achieve fulfillment or functionality. While initially rooted in political philosophy, autarkeia later became a cornerstone in ethical and individualist thought, particularly in the works of the Cynics, Stoics, and Epicureans.

Key philosophers:

- Aristotle: Explored autarkeia in political contexts, emphasizing the self-sufficiency of the city-state as the foundation of autonomy and stability.

- Diogenes of Sinope: Promoted ethical autarkeia through radical independence from material needs and social conventions.

- Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius: Stoic philosophers who connected autarkeia with inner tranquility and mastery over emotions and desires.

- Epicurus: Advocated for a form of autarkeia achieved through a simple life and the pursuit of intellectual and social pleasures.

Political origins

In early Greek thought, particularly in the works of Aristotle, autarkeia was primarily a political concept. In Politics, Aristotle defines a city-state (πόλις) as achieving autarkeia when it becomes self-sufficient in providing for its citizens’ needs, such as food, security, and governance. This political self-sufficiency was considered the foundation of stability and autonomy.

Ethical development

The ethical dimension of autarkeia evolved with the rise of philosophical schools that emphasized personal virtue and inner peace. Here, autarkeia shifted from a political ideal to an individual one, focusing on the independence of the soul from external circumstances.

Cynicism

The Cynics were among the earliest proponents of ethical autarkeia. Diogenes of Sinope, a key figure in Cynicism, argued that true self-sufficiency could only be achieved by renouncing material possessions and social conventions. For the Cynics, autarkeia was a radical form of independence, requiring complete freedom from external needs and reliance solely on virtue and reason.

Stoicism

In Stoicism, autarkeia became closely associated with inner tranquility and resilience. Stoics like Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius taught that self-sufficiency lies in the alignment of one’s will with nature and the rational order of the cosmos. External goods, such as wealth or status, were considered indifferent (ἀδιάφορα), and true autarkeia was achieved by mastering one’s desires and emotions through reason and virtue.

Epicureanism

Epicurus also emphasized autarkeia but framed it in terms of the simple life and the pursuit of pleasure (defined as the absence of pain and disturbance). For Epicureans, autarkeia was the ability to find contentment with minimal material needs, focusing instead on intellectual pleasures, friendship, and freedom from fear.

Philosophical significance

Autarkeia represents a broader philosophical ideal of independence and self-mastery that transcends its specific interpretations in individual schools. It challenges individuals to evaluate their dependencies, whether material, emotional, or societal, and to cultivate an inner source of stability and fulfillment. In doing so, autarkeia bridges ethical, political, and metaphysical dimensions, influencing not only ancient philosophy but also modern discussions of autonomy and self-reliance.

Demiurge

The Demiurge (Greek: Δημιουργός, “craftsman” or “artisan”) is a central concept in later Greek philosophy, particularly in Plato’s Timaeus and subsequent Neoplatonic and Gnostic thought. The Demiurge is depicted as a divine creator who shapes the material world, imposing order upon chaos by using eternal Forms as archetypes.

Key philosophers:

- Plato: Introduced the concept of the Demiurge in Timaeus, emphasizing its role as a rational and benevolent craftsman shaping the cosmos.

- Philo of Alexandria: Integrated the Platonic Demiurge into Jewish monotheistic frameworks, presenting it as a divine intermediary.

- Plotinus: Reinterpreted the Demiurge as the Nous, a manifestation of the divine intellect in Neoplatonism.

- Valentinian Gnostics: Transformed the Demiurge into a malevolent force in their cosmological dualism.

Plato’s Demiurge

Plato introduces the Demiurge in his dialogue Timaeus as a rational and benevolent craftsman. Unlike the gods of myth, the Platonic Demiurge is not a supreme deity but a metaphysical principle that bridges the perfect realm of Forms with the imperfect material world. The Demiurge works with pre-existing chaotic matter (the Receptacle or Khōra) to create a cosmos that reflects the order and harmony of the Forms.

- Role in creation: The Demiurge uses reason and the Good as guiding principles to fashion the cosmos. For Plato, this creative act explains the presence of order, beauty, and purpose in the universe.

- Non-omnipotence: The Demiurge’s creation is limited by the inherent imperfections of matter, which resists perfect realization of the Forms.

Middle Platonism

During the period of Middle Platonism (1st century BCE to 3rd century CE), the Demiurge was reinterpreted and integrated into broader metaphysical systems. Philosophers such as Philo of Alexandria identified the Demiurge with the God of monotheistic traditions, emphasizing its role as a supreme creator and a bridge between the divine and the material.

- Ethical implications: The Demiurge’s rational and benevolent nature served as a model for human virtue, reflecting the alignment of reason with the Good.

- Cosmological significance: The Demiurge’s creative act provided a framework for understanding the origin and structure of the cosmos.

Gnosticism

In Gnostic traditions, the Demiurge undergoes a dramatic transformation. Far from being a benevolent creator, the Gnostic Demiurge is often portrayed as an ignorant or malevolent being responsible for the flawed material world. Gnostic texts, such as the Apocryphon of John from the Nag Hammadi Library, describe the Demiurge (often named Ialdabaoth) as a deluded entity who falsely claims to be the ultimate god.

- Dualism: Gnosticism posits a stark dualism between the spiritual realm (associated with a transcendent, unknowable God) and the material world (governed by the Demiurge and its Archons).

- Salvation: In Gnostic cosmology, human souls contain divine sparks trapped in the material world. Liberation from the Demiurge’s dominion requires gnosis—esoteric knowledge of one’s true spiritual nature.

Influence on Neoplatonism

In Neoplatonism, particularly the works of Plotinus, the Demiurge is reinterpreted as the Nous (Divine Intellect), the second hypostasis in the hierarchy of being. Plotinus’s Demiurge does not act upon chaotic matter but emanates order from the One, the ultimate source of all existence.

- Unified cosmology: The Neoplatonic Demiurge integrates creation into a hierarchical structure where all levels of reality flow from the One.

- Mystical ascent: Neoplatonism emphasizes the soul’s journey back to the One, transcending the material world shaped by the Demiurge.

Impact on Christianity

The concept of the Demiurge had a profound influence on early Christian theology and debates about creation, divine justice, and the problem of evil:

- Orthodox Christianity: While rejecting Gnostic dualism, early Church Fathers like Origen engaged with Platonic ideas, aligning the Christian God with the rational and benevolent aspects of Plato’s Demiurge.

- Problem of evil: The inherent imperfections in the material world, attributed to the resistance of chaotic matter in Platonic thought, informed theological discussions on the origins of sin and suffering.

Dikaiosyne

Dikaiosyne (δικαιοσύνη) translates to “justice” or “righteousness” in classical Greek. It encompasses fairness, moral integrity, and adherence to ethical principles in both personal conduct and societal structures. The term reflects the ideal of living in harmony with laws, reason, and virtue, playing a central role in Greek ethical and political philosophy.

Key philosophers:

- Homer: Laid the groundwork for justice as social and divine order.

- Plato: Defined justice as harmony within the individual and society, linked to the ultimate Good.

- Aristotle: Distinguished forms of justice and emphasized proportionality in ethical and political contexts.

- Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius: Advocated justice as a Stoic virtue, essential for living in harmony with reason and nature.

- Epicurus: Framed justice as a practical agreement fostering peace and security.

Homeric tradition

In Homeric epics, dikaiosyne is often portrayed in terms of social and divine order. Justice involves fulfilling one’s role within the community and respecting the decrees of the gods. Leaders like Agamemnon and Odysseus are judged based on their ability to uphold justice in their actions and decisions, maintaining balance and order.

Plato

For Plato, dikaiosyne is one of the cardinal virtues, essential for both the individual and the state. In the Republic, Plato defines justice as a condition in which every individual fulfills their appropriate role within society, creating harmony between its classes. On a personal level, justice is the harmonious functioning of the soul, where reason governs spirit and appetite, aligning the individual with the Good (to agathon). Justice, in this sense, is both a moral and metaphysical principle.

Aristotle

Aristotle provides a detailed analysis of dikaiosyne in the Nicomachean Ethics and Politics. He distinguishes between general justice, which encompasses all virtues in relation to others, and particular justice, which pertains to fairness in distribution and rectification. Aristotle’s view emphasizes proportionality—treating equals equally and unequals unequally according to their merits—as the foundation of justice. He also explores legal justice, which aligns human laws with the natural order.

Stoicism

The Stoics regard dikaiosyne as a fundamental virtue, rooted in living according to nature and reason. Justice, for the Stoics, involves recognizing the interconnectedness of humanity and acting in ways that promote the common good. Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus highlight justice as central to a virtuous life, emphasizing fairness, compassion, and duty to others.

Epicureanism

For the Epicureans, dikaiosyne is a social contract established to ensure mutual security and tranquility. Justice is not intrinsic but instrumental, arising from agreements that prevent harm and promote harmonious coexistence. Epicurus ties justice to the absence of fear and conflict, aligning it with the pursuit of a peaceful life.

Historical development and influence

The concept of dikaiosyne has profoundly shaped Western thought, influencing legal, ethical, and political systems. Its emphasis on fairness, order, and the common good continues to inform debates about justice, rights, and moral responsibility in contemporary philosophy and society.

Dogma

Dogma (δόγμα) translates to “opinion”, “belief”, or “teaching” in classical Greek. In its philosophical usage, it refers to doctrines or principles considered authoritative and unchanging, often serving as the foundation for ethical, metaphysical, or epistemological systems. While the term evolved to acquire theological connotations, in ancient philosophy, it had a broader application.

Key philosophers:

- Epictetus: Highlighted dogmata as rational principles guiding Stoic practice.

- Sextus Empiricus: Criticized dogmatism as a barrier to tranquility and philosophical openness.

- Epicurus: Presented clear and actionable dogmata to guide individuals toward a life free of fear and disturbance.

Stoicism

In Stoic philosophy, dogma refers to foundational principles or axioms derived from reason and aligned with nature. These doctrines guide the Stoic way of life, emphasizing the pursuit of virtue as the highest good and the alignment of human action with universal reason (logos). Stoics such as Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius regarded adherence to dogmata as essential for achieving inner peace and living in harmony with the cosmos.

Skepticism

For Skeptics, particularly in the Pyrrhonian tradition, dogma is viewed with suspicion. Sextus Empiricus criticizes the rigid adherence to dogmata, arguing that it leads to dogmatism and mental disturbance. Skeptics advocate for the suspension of judgment (epoché), rejecting fixed beliefs in favor of ongoing inquiry and tranquility (ataraxia).

Epicureanism

In Epicurean philosophy, dogma represents the core teachings of Epicurus, such as the pursuit of pleasure (hedone) and the avoidance of pain as the ultimate goals of life. These doctrines are presented as rational principles that liberate individuals from fear of the gods and death, fostering a life of simplicity and tranquility.

Plato and Aristotle

While Plato and Aristotle do not explicitly use the term dogma in their philosophical systems, their teachings have been interpreted as embodying foundational doctrines. Plato’s theory of Forms and Aristotle’s principles of causation and virtue ethics serve as enduring dogmata in the history of philosophy.

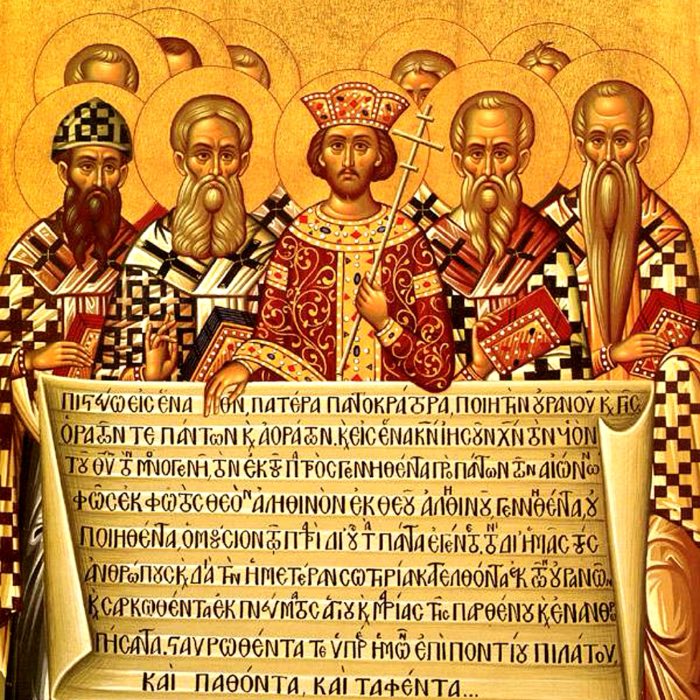

Early Christian thought

In the development of Christian theology, dogma acquires a more specific meaning, referring to authoritative teachings or doctrines of the Church. Early Christian councils, such as the Council of Nicaea, formulated dogmata to establish orthodox beliefs and combat heresy. These creeds and declarations became foundational to Christian faith and practice.

Historical development and influence

The concept of dogma has had a profound impact on the development of philosophical and theological traditions. While in its classical usage, it often referred to guiding principles, its later adoption in religious contexts emphasized immutable truths. The tension between adhering to dogmata and maintaining intellectual openness continues to influence contemporary debates in philosophy, science, and theology.

Episteme

Episteme (ἐπιστήμη) translates to “knowledge” or “understanding” in classical Greek. It represents a systematic, rational, and demonstrable form of knowledge, often contrasted with opinion (doxa). In philosophical contexts, episteme encompasses the pursuit of true knowledge grounded in reason and principles, distinguishing it from mere perception or belief.

Key philosophers:

- Plato: Elevated episteme as knowledge of the eternal and unchanging Forms.

- Aristotle: Defined episteme as demonstrative knowledge derived from first principles, foundational to scientific inquiry.

- Epictetus: Emphasized the Stoic ideal of episteme as knowledge aligned with reason and virtue.

- Sextus Empiricus: Critiqued the possibility of achieving episteme, advocating for suspension of judgment.

- Epicurus: Highlighted the role of episteme in liberating individuals from fear through understanding the natural world.

Plato

For Plato, episteme is central to his theory of knowledge and metaphysics. In dialogues like the Republic and the Theaetetus, Plato contrasts episteme with doxa, emphasizing that true knowledge is concerned with the eternal and unchanging Forms, rather than the transient and imperfect world of sensory experience. The allegory of the cave vividly illustrates this distinction, showing how episteme involves an intellectual ascent from the shadows of illusion to the light of truth.

Aristotle

Aristotle refines the concept of episteme in his works, particularly in the Posterior Analytics. For him, episteme is a form of demonstrative knowledge derived from first principles (archai). These principles are self-evident truths from which other propositions can be logically deduced. Aristotle distinguishes episteme from practical knowledge (phronesis) and productive knowledge (techne), situating it as the foundation of scientific inquiry and theoretical understanding.

Stoicism

In Stoic philosophy, episteme represents the ideal state of knowledge achieved by the sage. The Stoics argue that true knowledge is certain and based on kataleptic impressions (“clear and distinct perceptions”) that align with the rational order of the cosmos. For the Stoics, episteme is intimately tied to living virtuously, as knowledge and virtue are inseparable.

Skepticism

Skeptics, particularly in the Pyrrhonian tradition, challenge the possibility of attaining episteme. Sextus Empiricus argues that because all claims to knowledge are subject to doubt, suspending judgment (epoché) is the most rational response. This suspension leads to mental tranquility (ataraxia), in contrast to the certainty sought by other philosophical schools.

Epicureanism

While the Epicureans focus on practical knowledge that contributes to a life free from fear and disturbance, they also recognize a role for episteme in understanding the natural world. Epicurus emphasizes the importance of studying nature to dispel irrational fears of gods and death, grounding episteme in empirical observation and rational inference.

Historical development and influence

The concept of episteme has profoundly influenced the development of epistemology, science, and philosophy. Its distinctions from belief, practical knowledge, and empirical observation continue to inform debates about the nature and limits of human understanding.

Epoché

Epoché (ἐποχή) translates to “suspension” or “cessation” in classical Greek. In philosophical contexts, it signifies the suspension of judgment about the truth or falsity of propositions. Originating in ancient Skepticism, epoché is a methodological tool used to achieve mental tranquility (ataraxia) by refraining from making definitive assertions about uncertain matters.

Key philosophers and thinkers:

- Sextus Empiricus: Articulated epoché as a means to achieve mental tranquility in Skepticism.

- Arcesilaus and Carneades: Incorporated epoché into Academic skepticism, combining it with probabilistic reasoning.

- Chrysippus: Critiqued epoché from a Stoic perspective, emphasizing the reliability of kataleptic impressions.

- Edmund Husserl: Reinterpreted epoché as a phenomenological method for examining pure consciousness.

Pyrrhonian skepticism

The concept of epoché is central to Pyrrhonian skepticism, as developed by Sextus Empiricus. Skeptics argue that for every argument, an equally persuasive counterargument can be made, leading to a state of isosthenia (balance of opposing views). Faced with this equilibrium, the Skeptic suspends judgment (epoché), neither affirming nor denying any claim. This suspension fosters ataraxia, a state of peace free from the disturbances of dogmatic belief.

Academic skepticism

Although the Academic Skeptics, such as Arcesilaus and Carneades, share similarities with Pyrrhonian skepticism, their approach to epoché differs. Academic Skeptics use suspension of judgment as a provisional stance while engaging in probabilistic reasoning to navigate practical life. For them, epoché serves as a philosophical starting point rather than an ultimate goal.

Stoicism

The Stoics criticize epoché for its rejection of certainty. They argue that kataleptic impressions (clear and undeniable perceptions) provide a basis for certain knowledge, rendering suspension of judgment unnecessary. However, the Stoics recognize the value of careful deliberation and the avoidance of hasty conclusions in maintaining rationality.

Phenomenology

In modern philosophy, epoché is revived by Edmund Husserl in the context of phenomenology. Husserl employs epoché as a methodological suspension of all naturalistic and metaphysical assumptions to focus purely on the contents of consciousness. By bracketing out preconceptions, phenomenologists aim to examine phenomena as they appear, leading to a more precise understanding of subjective experience.

Historical development and influence

The concept of epoché has profoundly shaped the history of philosophy, influencing ancient Skepticism, Stoicism, and modern phenomenology. Its emphasis on withholding judgment continues to resonate in contemporary epistemology, ethics, and methodology, offering insights into the nature of belief, doubt, and inquiry. epoché remains a vital tool for cultivating intellectual openness and critical reflection.

Eudaimonia

Eudaimonia (εὐδαιμονία) translates to “flourishing”, “happiness”, or “the good life” in classical Greek. It represents the highest human good and the ultimate aim of life, encompassing a state of fulfillment and well-being achieved through virtuous living and the realization of one’s potential.

Key philosophers:

- Socrates: Identified virtue and self-examination as the core of eudaimonia.

- Plato: Linked eudaimonia to the realization of justice and alignment with the Good.

- Aristotle: Defined eudaimonia as a life of virtuous activity in accordance with reason.

- Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius: Advocated the Stoic ideal of flourishing through rationality and virtue.

- Epicurus: Emphasized the role of pleasure, tranquility, and the avoidance of pain in achieving happiness.

Socratic philosophy

Socrates redefined happiness as a result of living a virtuous and examined life. In Socratic thought, eudaimonia is intrinsically linked to moral virtue and wisdom, as ignorance leads to moral failure and unhappiness. Socrates emphasized that eudaimonia is not achieved through external possessions but through the cultivation of the soul and ethical reasoning.

Plato

For Plato, eudaimonia is the harmonious alignment of the soul, achieved through justice and the other cardinal virtues: wisdom, courage, and moderation. In the Republic, Plato describes eudaimonia as living in accordance with the Good (to agathon), the highest metaphysical principle. Knowledge of the Good, attained through philosophical inquiry, enables an individual to live a fully realized and virtuous life.

Aristotle

Aristotle’s conception of eudaimonia, as detailed in the Nicomachean Ethics, emphasizes it as the ultimate end (telos) of human life. For Aristotle, eudaimonia is not a transient emotional state but a lifelong activity of virtuous practice in accordance with reason. He distinguishes between intellectual virtues (sophia, theoretical wisdom) and moral virtues (phronesis, practical wisdom), both of which contribute to achieving eudaimonia. External goods, such as health and friendship, are also considered supportive conditions but not determinants of true happiness.

Stoicism

In Stoic philosophy, eudaimonia is synonymous with living in harmony with nature and reason. The Stoics argue that virtue alone is sufficient for achieving eudaimonia, as external factors are beyond one’s control and therefore irrelevant to true flourishing. By focusing on the development of rationality and self-discipline, Stoics maintain tranquility (ataraxia) and resilience in the face of adversity.

Epicureanism

For Epicurus, eudaimonia is closely tied to pleasure (hedone), specifically the absence of pain (aponia) and mental disturbance (ataraxia). Epicurus teaches that by satisfying natural and necessary desires, avoiding vain pursuits, and cultivating friendships, one achieves a state of lasting tranquility and happiness.

Historical development and influence

The concept of eudaimonia has shaped ethical theories throughout history, from ancient virtue ethics to contemporary discussions of well-being and human flourishing. Its emphasis on moral development and purposeful living continues to inform modern philosophical, psychological, and social approaches to happiness and fulfillment.

Eusebeia

Eusebeia (εὐσέβεια) translates to “piety”, “reverence”, or “devotion” in classical Greek. It signifies a deep respect for the divine, a commitment to religious duties, and a harmonious relationship with the gods, society, and moral principles. In philosophical contexts, it reflects the integration of spiritual and ethical dimensions of life.

Key philosophers:

- Socrates: Reframed eusebeia as an ethical and philosophical pursuit beyond mere ritual observance.

- Plato: Linked piety to justice and the philosophical understanding of divine principles.

- Aristotle: Incorporated eusebeia into his framework of justice and moral virtue.

- Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius: Advocated a Stoic interpretation of piety as rational reverence for the divine order.

Homeric tradition

In the Homeric epics, eusebeia is portrayed as reverence for the gods and adherence to rituals and customs. Characters demonstrate eusebeia through sacrifices, prayers, and respect for divine authority, which ensures favor and avoids divine wrath. Piety is closely tied to maintaining social and cosmic order.

Socratic philosophy

Socrates challenges conventional notions of eusebeia in dialogues like the Euthyphro. He seeks a deeper understanding of piety beyond ritualistic observance, questioning whether acts are pious because the gods approve them or if the gods approve them because they are inherently pious. This inquiry shifts eusebeia toward an ethical and philosophical examination of justice, morality, and the divine.

Plato

Plato extends the discussion of eusebeia as part of a just and virtuous life. In his works, piety is linked to the broader concept of justice (dikaiosyne) and the alignment of the soul with the Good (to agathon). True eusebeia, for Plato, involves not only fulfilling religious obligations but also understanding and aligning with divine principles through reason and philosophical inquiry.

Aristotle

While Aristotle does not focus extensively on eusebeia, he incorporates it into his ethical framework as part of justice. In the Nicomachean Ethics, he describes piety as a form of distributive justice, giving the gods their due through worship and respect. For Aristotle, eusebeia contributes to the harmonious functioning of society and the individual’s moral development.

Stoicism

For the Stoics, eusebeia is integral to living in accordance with nature and reason. It involves recognizing the divine rational order of the cosmos and aligning one’s actions with it. Piety, in this sense, is not confined to religious rituals but extends to a rational and virtuous life that honors the divine principles governing existence.

Historical development and influence

The concept of eusebeia has influenced religious, ethical, and philosophical traditions throughout history. Its emphasis on reverence, moral integrity, and alignment with higher principles continues to resonate in discussions of spirituality, ethics, and the role of religion in human life.

Hexis

Hexis (ἕξις) translates to “state”, “habit”, or “disposition” in classical Greek. It signifies a stable and enduring quality of character or being, formed through repeated actions or practices. In philosophical contexts, hexis refers to the cultivated traits or conditions that shape an individual’s ethical and intellectual life.

Key philosophers:

- Aristotle: Defined hexis as a stable disposition formed through habituation, central to his virtue ethics.

- Epictetus: Advocated for the Stoic practice of cultivating enduring qualities aligned with reason.

- Epicurus: Emphasized habits that lead to lasting tranquility and freedom from pain.

- Plato: Implicitly acknowledged the role of cultivated dispositions in ethical and intellectual development.

Aristotle

Aristotle provides the most systematic treatment of hexis in his ethical and metaphysical works. In the Nicomachean Ethics, he describes hexis as a disposition that results from habituation (ethos). For Aristotle, virtues are hexeis (plural of hexis), stable dispositions that enable individuals to act in accordance with reason and the “golden mean” between excess and deficiency. For example, courage is a hexis that balances recklessness and cowardice. Similarly, intellectual virtues such as wisdom (sophia) and practical reason (phronesis) are hexeis developed through study and reflection.

In metaphysics, hexis is understood as the state of possessing or being in a particular condition, as opposed to a transient state. This broader understanding highlights the enduring and formative nature of hexis in shaping both character and reality.

Stoicism

While the Stoics do not use the term hexis extensively, their philosophy aligns with its principles. The Stoics emphasize the importance of cultivating stable and virtuous dispositions through rational practice and alignment with the natural order. For the Stoics, a virtuous life requires developing enduring qualities, akin to Aristotle’s hexeis, that enable individuals to remain resilient and rational in the face of external challenges.

Epicureanism

The Epicureans also touch on concepts related to hexis through their emphasis on cultivating habits that lead to tranquility (ataraxia). Although not explicitly using the term, their focus on developing consistent practices to avoid pain and achieve mental stability reflects the essence of hexis as a stable and beneficial disposition.

Platonic thought

In Plato’s works, the idea of hexis can be inferred from his discussions of education and the development of virtues. Plato emphasizes the importance of repetitive practice and philosophical inquiry in shaping the soul’s orientation toward the Good (to agathon). While he does not use the term hexis explicitly, the cultivation of virtuous habits aligns with its meaning.

Historical development and influence

The concept of hexis has had a profound impact on ethical philosophy, particularly in discussions of virtue ethics and character formation. Its emphasis on stability, repetition, and the development of enduring qualities continues to influence contemporary debates about moral education, self-improvement, and the cultivation of excellence.

Hybris

Hybris (ὕβρις) translates to “excessive pride”, “arrogance”, or “outrage” in classical Greek. It refers to an overstepping of bounds, often through acts of insolence, disrespect, or overconfidence that challenge the natural or divine order. In both literary and philosophical contexts, hybris is closely associated with moral failure and serves as a warning against excessive self-assertion.

Key philosophers and thinkers:

- Homer: Depicted hybris as a violation of divine and societal order, punished by the gods.

- Sophocles and Euripides: Explored hybris in tragedy as a driving force of human downfall.

- Plato: Identified hybris as an imbalance within the soul that undermines justice and reason.

- Aristotle: Analyzed hybris as a deliberate act of arrogance, central to ethical and tragic failure.

- Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius: Advocated for humility and rationality to counter the destructive effects of hybris.

Homeric tradition

In Homeric epics, hybris is portrayed as a grave offense against the gods and societal norms. Characters who display hybris, such as Agamemnon in his conflicts with Achilles, disrupt the harmony of the community and often suffer dire consequences. Hybris in this context reflects the dangers of unchecked ambition or arrogance that defies divine or communal authority.

Tragedy

In Greek tragedy, hybris plays a central role in the downfall of protagonists. Figures like Oedipus in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex or Pentheus in Euripides’ The Bacchae exemplify how excessive pride or defiance of divine will leads to catastrophic outcomes. The concept serves as a moral and dramatic lesson about the necessity of humility and respect for limits.

Plato

In Platonic philosophy, hybris is viewed as a disruption of the soul’s harmony. In dialogues such as the Republic, Plato identifies hybris with an imbalance where desires and appetites overpower reason, leading to injustice and moral decay. For Plato, the cultivation of virtues like moderation (sophrosyne) is essential to counteract the destructive tendencies of hybris.

Aristotle

Aristotle analyzes hybris in his Rhetoric and Poetics. In the Rhetoric, he defines it as an intentional act that brings shame or harm to others, motivated by a sense of superiority rather than necessity. In the Poetics, Aristotle links hybris to the tragic flaws (hamartia) of characters whose excessive pride blinds them to reality and leads to their downfall. For Aristotle, hybris is an ethical failure rooted in an imbalance of character.

Stoicism

The Stoics regard hybris as a failure to live in accordance with reason and nature. They emphasize the dangers of arrogance and overconfidence, advocating instead for humility and self-awareness as key virtues. Hybris disrupts the Stoic ideal of inner harmony and rational self-control, leading to irrational and destructive behaviors.

Historical development and influence

The concept of hybris has had a lasting impact on Western thought, shaping literary, ethical, and philosophical traditions. Its warnings against excessive pride and disregard for limits remain relevant in discussions of morality, leadership, and human behavior. Hybris continues to serve as a cautionary principle in both classical studies and contemporary ethical discourse.

Kairos

Kairos (καιρός) translates to “the right time”, “opportune moment”, or “critical occasion” in classical Greek. It signifies a qualitative concept of time, focusing on the timeliness and appropriateness of actions rather than the quantitative measurement of time (chronos). In philosophical and rhetorical contexts, kairos emphasizes the importance of seizing the right moment to act or speak effectively.

Key philosophers and thinkers:

- Gorgias and Protagoras: Developed kairos as a cornerstone of rhetorical adaptability and effectiveness.

- Plato: Highlighted the implicit role of timing and context in philosophical dialogue and ethical persuasion.

- Aristotle: Systematized kairos as part of rhetorical theory, emphasizing its role in persuasion and audience engagement.

- Epictetus: Advocated for recognizing and acting on kairos in accordance with reason and virtue.

Homeric tradition

In Homeric epics, while the term kairos is not explicitly used, the concept is evident in the timing of heroic actions and decisions. Heroes like Odysseus exemplify the mastery of kairos by choosing the right moment to act decisively, whether in battle or in diplomacy, ensuring success and survival.

Sophists