The assimilation of Greek philosophy into the Roman Empire: Transmission, transformation, and further developments

The assimilation of Greek philosophy into the Roman Empire represents one of the most significant intellectual transitions in the history of Western thought. Beginning in the late Republic and flourishing during the early Empire, Greek philosophy became an integral part of Roman education, culture, and intellectual life. This transmission was facilitated by the Romans’ conquests of Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean, as well as by the enduring appeal of Greek philosophical ideas, which offered frameworks for addressing ethical, political, and metaphysical questions relevant to Roman society.

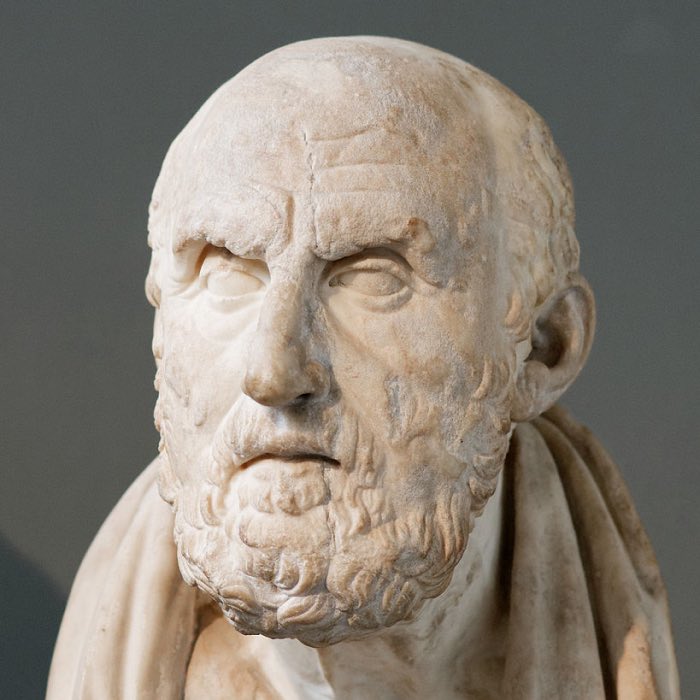

The Roman Empire around 117 CE, at its greatest extent. Greek philosophy profoundly influenced Roman thought and culture, shaping the intellectual landscape of the empire. Greek thought also had a deep impact on early Christian theology and the development of Christian philosophy. After the fall of the West-Roman Empire, Greek philosophy was preserved and transmitted both in upcoming Christianity and by Byzantine – and later Islamic – scholars, who played a crucial role in the preservation and transmission of classical knowledge.

Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Roman Empire around 117 CE, at its greatest extent. Greek philosophy profoundly influenced Roman thought and culture, shaping the intellectual landscape of the empire. Greek thought also had a deep impact on early Christian theology and the development of Christian philosophy. After the fall of the West-Roman Empire, Greek philosophy was preserved and transmitted both in upcoming Christianity and by Byzantine – and later Islamic – scholars, who played a crucial role in the preservation and transmission of classical knowledge.

Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The integration of Greek philosophy into the Roman world not only preserved its core traditions but also stimulated new developments, as Roman thinkers adapted and expanded these ideas to address their own cultural and practical concerns. The result was a synthesis of Greek and Roman intellectual traditions that shaped the course of Western philosophy and laid the foundations for subsequent developments in Christian and medieval thought.

The spread of Greek Philosophy in the Roman world

The Roman engagement with Greek philosophy began in earnest following the Roman conquest of Greece in the 2nd century BCE. Greek intellectuals, including philosophers, rhetoricians, and educators, were brought to Rome as captives, envoys, or voluntary migrants. Over time, they became influential figures in Roman society, teaching philosophy and rhetoric to Roman elites and introducing them to the works of Plato, Aristotle, and the Hellenistic schools.

By the late Republic, Greek philosophy had become a cornerstone of Roman education, particularly among the aristocracy. Wealthy Roman families sent their sons to study in Athens, Rhodes, and other centers of Greek learning, where they were exposed to the teachings of the Stoics, Epicureans, and Academics. Prominent Roman figures such as Cicero and Seneca were deeply influenced by Greek philosophical traditions, integrating them into their writings and public lives.

Philosophy also spread through the translation and dissemination of Greek texts. Roman scholars translated and adapted the works of Greek philosophers into Latin, making them accessible to a wider audience. Cicero, for example, translated and commented on the works of Plato and Aristotle, while Lucretius composed De Rerum Natura, a poetic exposition of Epicurean philosophy. These efforts not only preserved Greek philosophical traditions but also infused them with distinctly Roman perspectives and values.

Roman adaptations of Greek philosophy

The assimilation of Greek philosophy into the Roman Empire was not a passive process but an active reinterpretation that reflected the priorities and values of Roman society. Roman thinkers emphasized the practical and ethical dimensions of philosophy, adapting Greek ideas to address issues of personal conduct, political responsibility, and the nature of the good life.

Stoicism and Roman virtue

Stoicism, with its emphasis on reason, self-control, and living in accordance with nature, found particular resonance in Roman culture. Its teachings aligned with traditional Roman values such as duty, discipline, and the importance of serving the common good. Roman Stoics, including Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius, developed Stoic philosophy into a practical guide for ethical living, emphasizing the cultivation of inner resilience and the acceptance of fate.

Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations exemplifies the Roman adaptation of Stoicism, offering a personal reflection on the challenges of leadership and the pursuit of virtue. His writings highlight the Stoic principles of rationality, equanimity, and the interconnectedness of all human beings, demonstrating the compatibility of Stoic philosophy with the responsibilities of political and imperial power.

Epicureanism and the Roman quest for tranquility

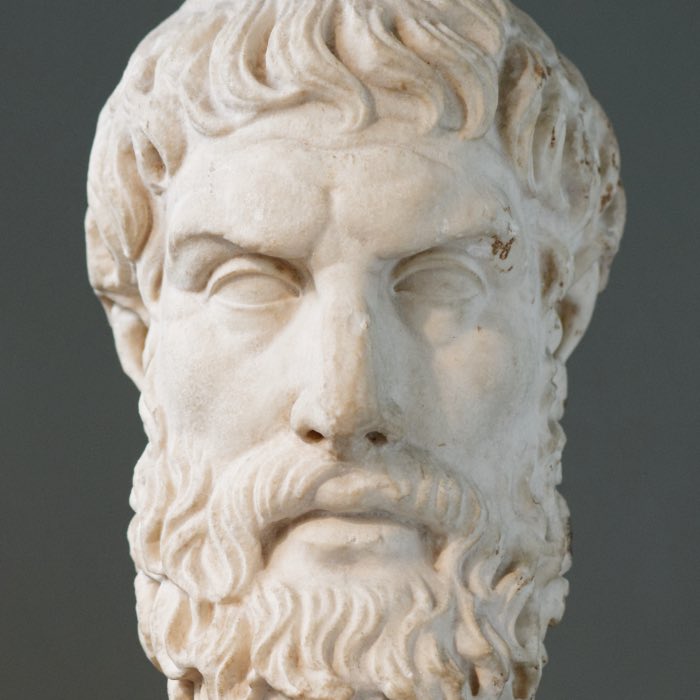

Epicureanism also gained followers in the Roman world, particularly among those seeking a philosophy of personal happiness and freedom from fear. While Epicureanism was often misunderstood and criticized for its hedonistic associations, Roman Epicureans emphasized its ethical core, which advocated for simplicity, friendship, and the avoidance of unnecessary desires.

Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura played a key role in introducing Epicurean ideas to a Roman audience, presenting a naturalistic and atomistic vision of the universe that challenged traditional religious and metaphysical beliefs. His work also reflected Roman concerns with stability and order, linking Epicurean teachings to the pursuit of personal and social harmony.

Platonism and the rise of Neoplatonism

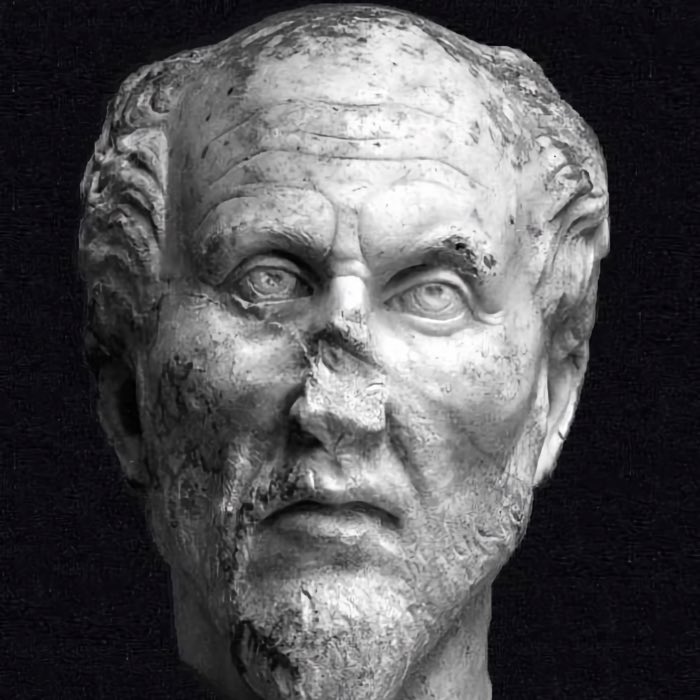

Platonism remained a significant intellectual tradition in the Roman Empire, influencing both pagan and Christian thinkers. In the later Roman period, Platonism evolved into Neoplatonism, a philosophical system developed by Plotinus and his followers that integrated Platonic, Aristotelian, and Stoic ideas into a unified metaphysical framework.

Neoplatonism emphasized the transcendence of the divine and the hierarchical structure of reality, offering a vision of spiritual ascent and unity with the One. This philosophical synthesis resonated with the religious and mystical tendencies of late antiquity, shaping the intellectual and spiritual landscape of the Roman Empire and beyond.

Further developments in philosophy

The assimilation of Greek philosophy into the Roman world not only preserved its core traditions but also stimulated new developments that reflected the unique concerns and contexts of Roman society.

Philosophy and politics

Roman philosophers explored the relationship between philosophy and politics, addressing questions of governance, justice, and the ethical responsibilities of rulers. Cicero, in particular, developed a political philosophy that combined Stoic and Platonic principles with Roman legal and civic traditions, emphasizing the importance of natural law, civic virtue, and the pursuit of the common good.

Philosophy and religion

The integration of Greek philosophy into the Roman Empire also facilitated a dialogue between philosophy and religion, particularly in the context of the emerging Christian tradition. Early Christian thinkers such as Augustine drew on Platonic and Stoic ideas to articulate theological concepts, such as the nature of God, the soul, and moral responsibility. Neoplatonism, with its emphasis on divine transcendence and spiritual ascent, played a particularly influential role in the development of Christian metaphysics and mysticism.

Philosophy and practical ethics

Roman philosophy placed a strong emphasis on practical ethics, providing guidance for navigating the challenges of daily life. Stoic exercises, such as self-reflection, mindfulness, and the contemplation of mortality, became integral to Roman ethical practice, offering tools for cultivating resilience, self-mastery, and inner peace.

Conclusion

The assimilation of Greek philosophy into the Roman Empire represents a pivotal chapter in the history of Western thought. Roman philosophers, educators, and translators preserved, adapted, and expanded the ideas of Plato, Aristotle, the Stoics, and the Epicureans, ensuring their transmission to subsequent generations. This engagement not only safeguarded Greek philosophical traditions but also revitalized them, addressing the unique concerns of Roman society and integrating them into new cultural and intellectual contexts.

The Roman adaptation of Greek philosophy exemplifies the transformative potential of cultural exchange, demonstrating how ideas can be reinterpreted and revitalized in response to historical and social challenges. It also shows the adaptability of the Roman Empire in absorbing and synthesizing diverse intellectual traditions, creating a rich philosophical thought. This synthesis laid the groundwork for the integration of classical philosophy into medieval scholasticism, Renaissance humanism, and modern philosophical traditions, influencing ongoing discussions of ethics, politics, and the human condition.

References and further reading

- Hellmut Flashar, Michael Erler, Günter Gawlick, Woldemar Görler, Peter Steinmetz, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd.4. Die hellenistische Philosophie, 1994, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796509308

- Christoph Riedweg, Christoph Horn, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 5. Die Philosophie der Kaiserzeit und der Spätantike, 2018, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796526299

- Hadot, P., Philosophy as a Way of Life: Spiritual Exercises from Socrates to Foucault, 2010, Blackwell, ISBN: 978-0631180333

- Griffin, M., Seneca: A Philosopher in Politics, 1992, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0198147749

- Long, A. A., Epictetus: A Stoic and Socratic Guide to Life, 2004, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199268856

comments