Greek mystery cults

Between the 6th century BCE and late antiquity, the Greek world witnessed the flourishing of numerous “mystery cults” that promised personal salvation, secret knowledge, and a sense of communion with the divine. Unlike the public, civic cults dedicated to Olympian gods, these more esoteric religions were defined by initiation rites that shielded certain doctrines and rituals from the uninitiated. Early Christianity would emerge within the broader context of these Hellenistic religious experiments, and any comparative study of Christian origins stands to benefit from an understanding of the mystery cults that shaped the intellectual and spiritual environment of the time.

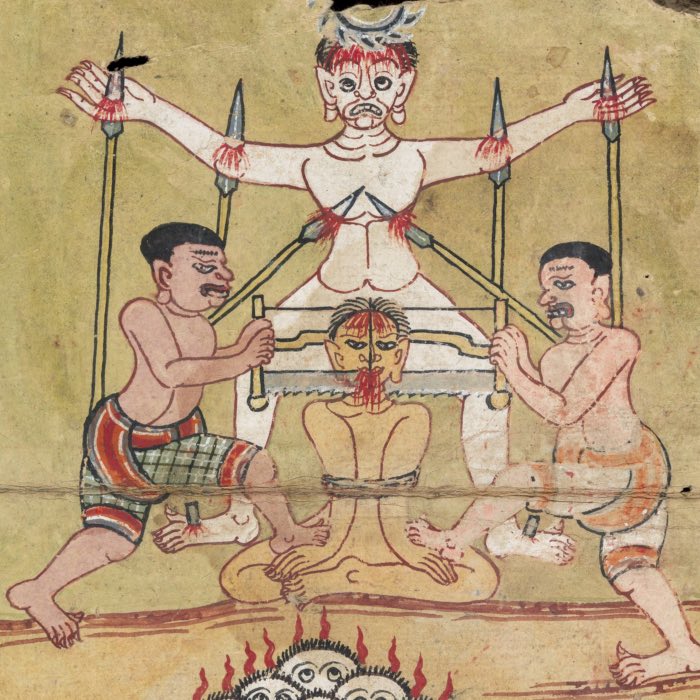

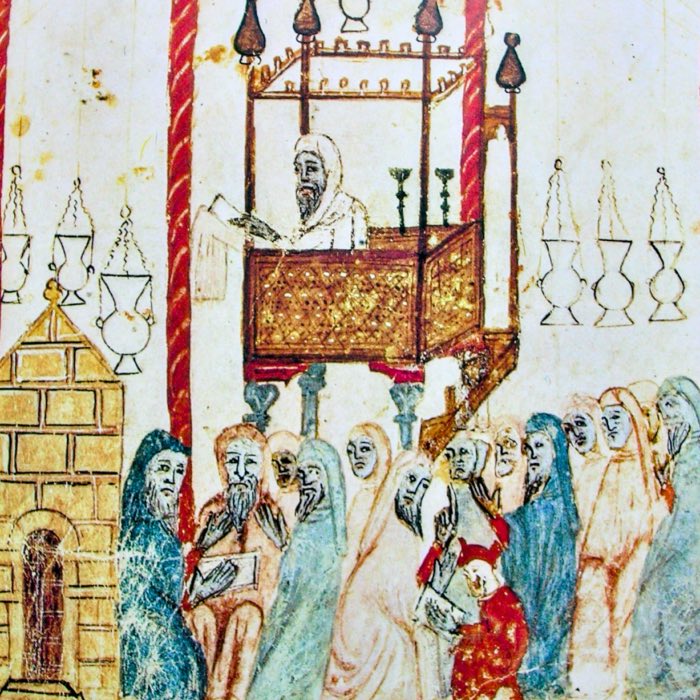

Example of an ancient Greek mystery cult: Triptolemos between Demeter (left), who hands him ears of corn, and Persephone (right), who blesses him. This scene derives from the Eleusinian mysteries, a prominent cult in ancient Greece. Roman copy of votive relief dating to the Early Imperial period (27 BCE - 14 CE). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Historical overview of greek mystery cults and their relation to classical greek philosophy

Greek mystery cults emerged around the 6th century BCE, during a period of significant transformation in the Greek world. As the polis (city-state) rose, fostering public religious life centered on Olympian deities, personal and esoteric forms of worship developed, giving birth to mystery cults.

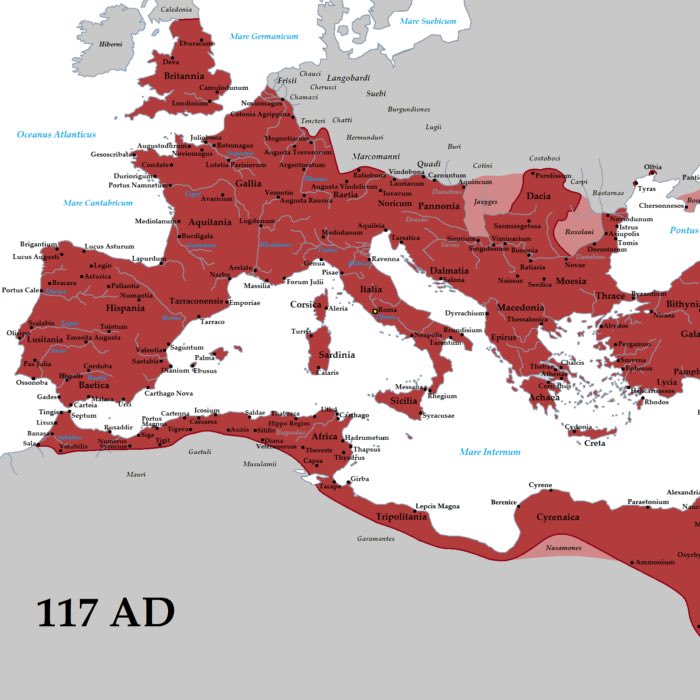

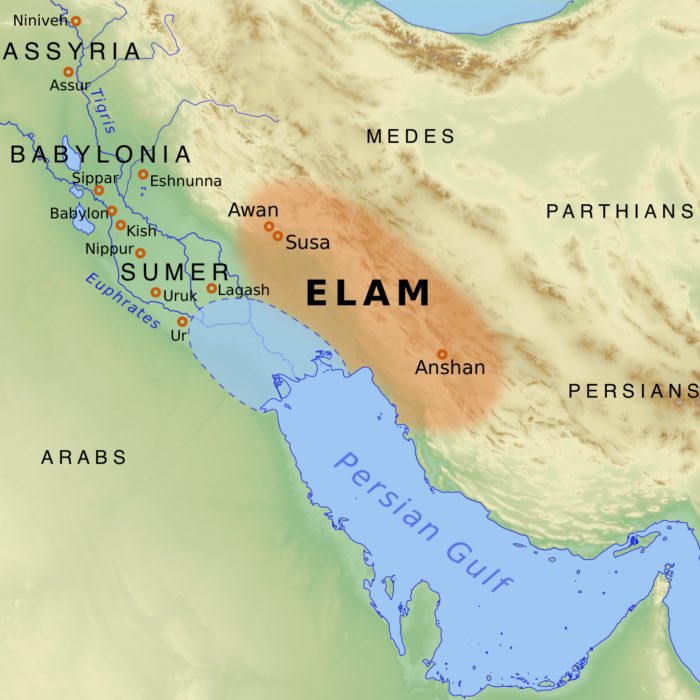

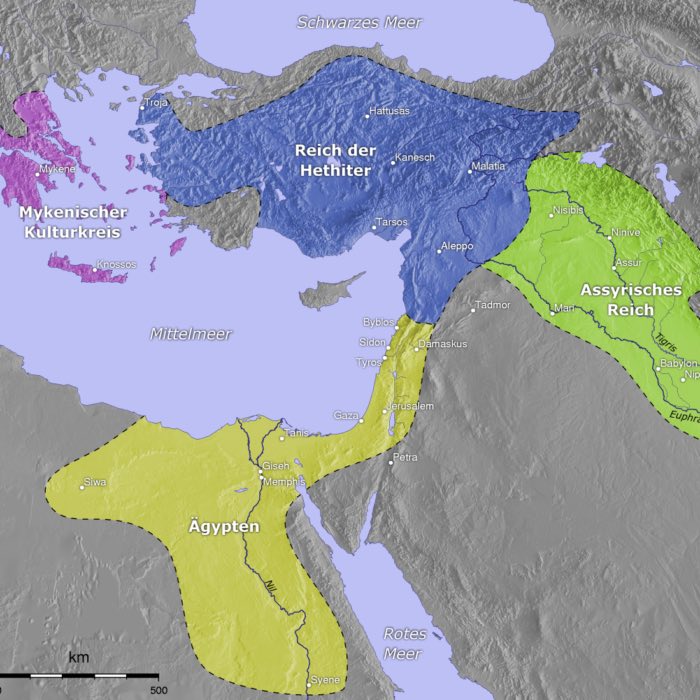

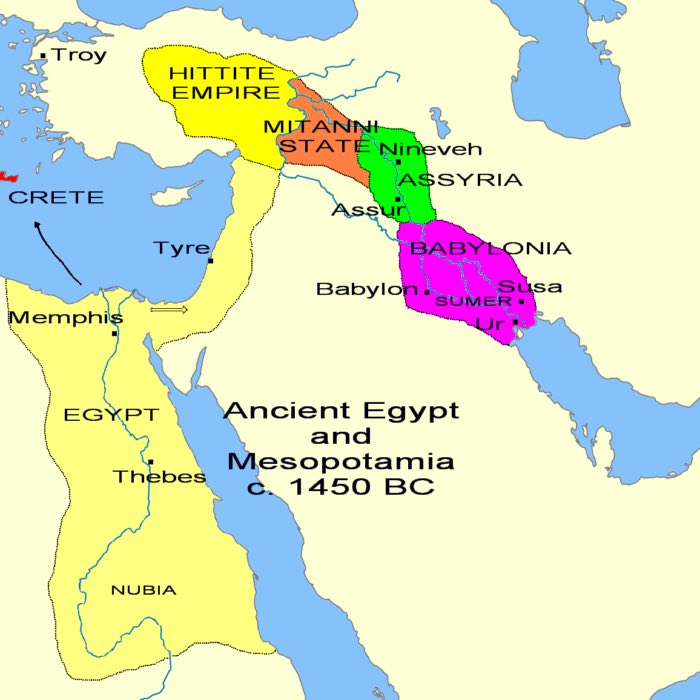

Early traditions like the Eleusinian mysteries likely evolved from pre-Hellenic agricultural rites. Over time, they formalized into elaborate initiatory systems. The Hellenistic period (4th to 1st century BCE) saw an expansion of these cults, influenced by increased Mediterranean cultural interaction and the blending of Greek religious forms with Egyptian, Persian, and Anatolian elements, resulting in hybrid cults such as those of Isis and Mithras.

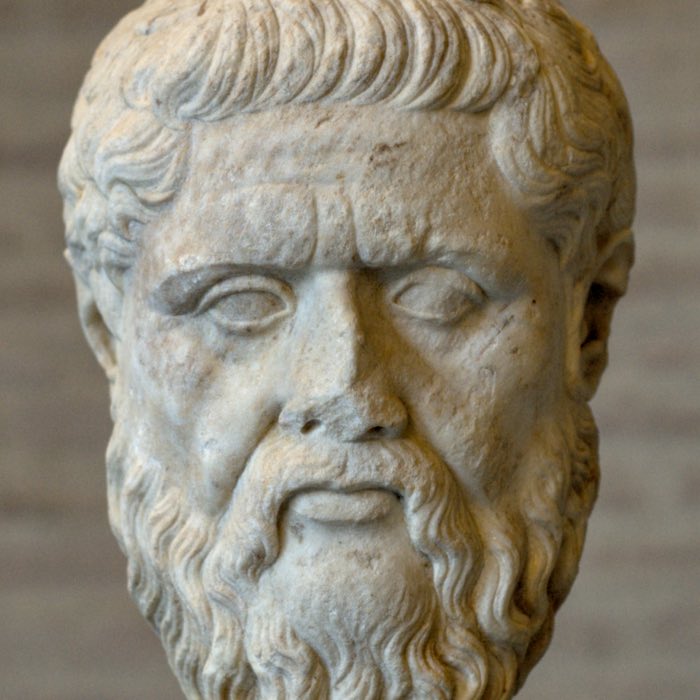

In parallel, Greek philosophy evolved from early thinkers like the Pre-Socratics, who sought to explain the cosmos through reason. Philosophers such as Heraclitus and Pythagoras shared affinities with the mystery traditions, emphasizing hidden truths and personal transformation. Pythagoreanism, with its initiatory practices and esoteric doctrines, closely mirrored mystery cult structures.

By the Classical period, philosophy and mystery cults had distinct but overlapping domains. While Plato and Aristotle distanced themselves from mythic elements, they engaged deeply with themes of the soul, immortality, and the divine. Plato, notably in the Phaedo and Symposium, used the language of initiation to explore the soul’s ascent to higher knowledge.

In the Hellenistic and Roman periods, schools like Stoicism and Neoplatonism incorporated elements of mystery cults. Neoplatonists, particularly Plotinus, viewed initiation as an allegory for the soul’s journey toward unity with the One, echoing the transformative experience of the mysteries.

Thus, Greek mystery cults and philosophy evolved in parallel, mutually influencing their approaches to understanding existence and the divine. Mystery cults offered experiential paths to salvation, while philosophy provided a rational framework for similar questions. Together, they shaped the spiritual and intellectual landscape of ancient Greece, influencing the broader development of Western thought.

Defining the mysteries

The term “mystery” (Greek: mystērion) in ancient religious contexts derived from “muō”, meaning “to close” or “to shut”, alluding to the secretive nature of the cultic practices. Initiates, known as mystai, were sworn to silence regarding the exact details of their rituals and teachings. This veil of secrecy gave the cults an aura of exclusivity and heightened their spiritual appeal. Rather than focusing on collective civic duties, the mysteries provided a personal religious experience: participants were said to gain knowledge about the afterlife and assurances of divine protection or immortality.

The role of initiation

Initiation into these cults often involved purification rites, sacrifices, dramatic reenactments of mythic episodes, and symbolic gestures conveying the transition from an “outsider” to an “insider.” Although these rites varied from one mystery cult to another, they shared a structure: the initiate faced a symbolic death or rebirth that transformed their status in both social and spiritual dimensions. Through this process, mystai believed they forged a special bond with the deity presiding over the cult — often a god or goddess who had themselves triumphed over death, hardship, or adversity.

Mythic narratives and ritual structures

Central myths of suffering and renewal

A salient feature of many Greek mysteries was a mythic narrative of suffering, death, and renewal. The stories of Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis, for example, illustrated themes of loss, descent into darkness, and eventual rebirth, all of which paralleled the cyclical changing of the seasons. In the Orphic and Dionysian traditions, participants encountered myths in which gods or heroes experienced dismemberment, torment, or traveling between realms, only to be restored or reborn. These narratives resonated with initiates’ own yearnings for spiritual regeneration.

Communal participation

Rituals within the mysteries often involved communal feasting, dances, sacred objects, and liturgical processions. While each cult had its distinctive symbols — the hiera (“sacred objects”) in Eleusis, the torches in Dionysian revels, or the bull-slaying imagery in the later mystery cult of Mithras — participation created profound group cohesion among initiates. Cultic gatherings could include theatrical performances that dramatized the central myth, reinforcing the parallels between the deity’s narrative and the initiate’s spiritual transformation.

Key examples of Greek mystery cults

- Eleusinian mysteries

Centered on the worship of Demeter and Persephone, the Eleusinian mysteries near Athens attracted initiates from across the Greek world. Their main promise was a blessed afterlife, tied to Demeter’s gift of agriculture and renewal of life. - Orphic mysteries

Based on the poetry attributed to Orpheus, an archetypal musician and underworld-traveler, Orphic traditions advocated ascetic practices and a distinct cosmology. They prized the idea that souls must undergo purification to break free from a cycle of rebirth. - Dionysian mysteries

Worshipers of Dionysus (or Bacchus) held ecstatic rituals involving wine, dance, and the dissolution of normal social boundaries. Mythic narratives of Dionysus’s death and return underscored themes of divine madness, frenzy, and the liberating power of divine life. - Mithraic mysteries (although not originally Greek, these later Roman-era mysteries were heavily influenced by Hellenistic modes of worship)

Centered on Mithras’s heroic acts, including his sacrificial slaying of a cosmic bull, the Mithraic cult featured complex underground temples, a hierarchy of initiatory grades, and a shared ritual meal.

Social function and appeal

A personal path to salvation

The greatest innovation of the mystery cults was their promise of personal salvation or rebirth. In contrast to mainstream Greek religion, which revolved around civic festivals and sacrifices aimed at preserving the welfare of the city-state, the mysteries addressed individual spiritual needs. By offering a sense of divine intimacy and an escape from post-mortem oblivion, they resonated especially with those who sought more direct and personal contact with the gods.

Cultural integration and syncretism

As Hellenistic and later Roman influence spread, these cults integrated local deities and customs with pan-Mediterranean ideas. The cult of Isis, for instance, imported from Egypt, adapted Greek concepts of mystērion to shape a new soteriological framework. The result was a tapestry of “hybrid” religious forms that flourished under different sociopolitical environments, each adopting local customs, languages, and theological motifs to appeal to broader segments of the population.

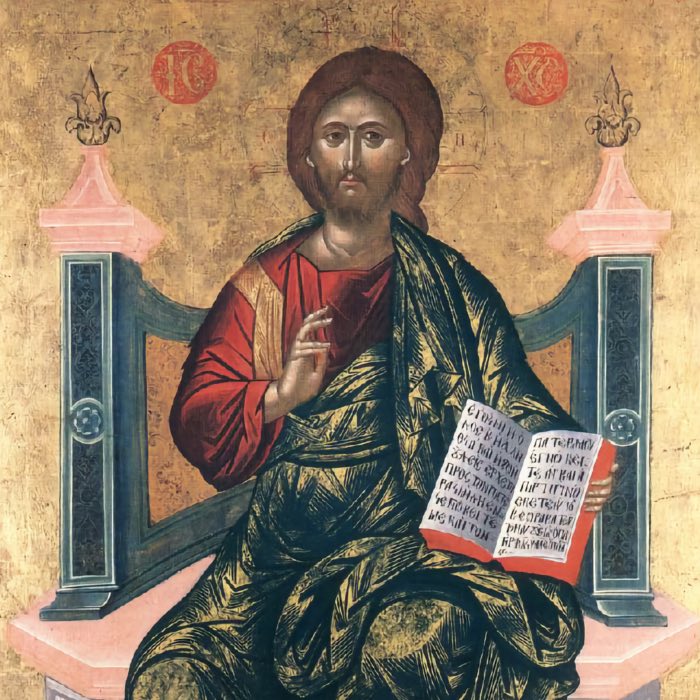

Influence on later religious movements

While it remains a subject of ongoing scholarly discussion, many researchers point out structural resemblances between Greek mysteries and the emerging Christian tradition. Baptismal rites, sacred meals, communal confessions, and narratives of the death and resurrection of a divine figure all bear striking parallels to the patterns established within earlier Greek (and more broadly Hellenistic) mystery cults.

Symbolism of death and rebirth

The Eleusinian mysteries, for example, emphasized themes of death, rebirth, and personal transformation through initiation rites centered on the myth of Demeter and Persephone. In Christianity, the ritual of baptism symbolizes a similar spiritual rebirth, with water functioning as a purifying element, akin to the cleansing rites in mystery cults. Sacred meals, such as the Eleusinian kykeon and the communal feasts in Dionysian mysteries, bear a conceptual resemblance to the Christian Eucharist, where the consumption of bread and wine signifies a profound union with the divine.

Communal aspects of worship

Communal participation was another shared feature. Mystery cult initiates often formed close-knit communities bound by shared rites and experiences, fostering a sense of belonging and spiritual support. Early Christian communities likewise emphasized mutual support, communal worship, and shared identity as followers of Christ. Both traditions offered a pathway to personal salvation and a means of transcending worldly suffering.

Comparative caution

Despite the parallels, scholars caution against simplistic comparisons — a critique often labeled as parallelomania. Mystery cults were not monolithic; each had distinct myths, practices, and social roles. Christianity, by contrast, emerged from a Jewish milieu with a unique monotheistic and scriptural heritage that shaped its doctrines in ways not wholly reducible to Hellenistic influence.

Nonetheless, the influence of Greek mystery cults on later religious movements remains significant, particularly regarding ritual practices, narrative themes, and communal structures. Baptismal rites, sacred meals, and resurrection narratives, central to Christian tradition, bear striking similarities to mystery cult motifs. Early Christianity also developed within a religious environment where these cults were popular and diverse across the Greek and Roman worlds. Thus, studying these shared elements provides valuable insights into how Christianity adapted and transformed existing spiritual motifs.

Conclusion

Greek mystery cults offered a transformative religious experience, centered on secret rites and personal salvation, that stood in contrast to the official public cults of the city-state. Their emphasis on individual spiritual renewal, eschatological hope, and ritual communion contributed to a religious climate in which new or adapted mystery religions could thrive. By understanding the structure, function, and social appeal of these earlier cults, scholars gain valuable context for examining the rise of Christianity and other late Hellenistic sects. Whether one sees direct influence or merely a shared cultural atmosphere, the study of Greek mystery cults remains indispensable for appreciating the varied spiritual landscapes of antiquity.

References and further reading

- Burkert, Walter, Ancient mystery cults, 1989, Harvard University Press, ISBN: 978-0674033870

- Mylonas, George Emmanuel, Eleusis and the Eleusinian mysteries, 2015, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691622040

- Graf, Fritz, Magic in the ancient world, 1999, Harvard University Press, ISBN: 978-0674541535

- Dillon, John, The Middle Platonists: 80 B.C. to A.D. 220, 1996, Cornell University Press, ISBN: 978-0801483165

- Bowden, Hugh, Mystery cults of the ancient world, 2023, Thames & Hudson Ltd, ISBN: 978-0500297278

- Richard Carrier, On the historicity of Jesus – Why we might have reason for doubt, 2014, Sheffield Phoenix Press, ISBN: 9781909697492

- Richard C. Carrier, Proving History: Bayes’s Theorem and the Quest for the Historical Jesus, 2012, Prometheus Books, ISBN: 978-1616145590

comments