Greek and Indian philosophy: A comparative analysis

Greek and Indian philosophies represent two of the most influential intellectual traditions in human history, both emerging independently but sharing certain common concerns: The nature of reality, the self, ethics, and the path to knowledge and wisdom. Despite arising in distinct cultural contexts, they exhibit parallels in their early developments, as well as significant differences in their metaphysical assumptions, methodologies, and ultimate goals. After exploring both traditions in separate post series, this post compares the development and characteristics of Greek and Indian philosophy, highlighting both their unique trajectories and shared themes.

Composite image of the Greek letter “Phi” and the “Om” ligature in Devanagari script. Om is used as a religious symbol in Hinduism. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical development

Greek philosophy

Greek philosophy began in the 6th century BCE with the pre-Socratic philosophers, who sought to explain the cosmos through reason rather than mythology. Thinkers like Thales, Heraclitus, and Parmenides laid the groundwork for metaphysical inquiry by asking fundamental questions about change, permanence, and the underlying substance of reality.

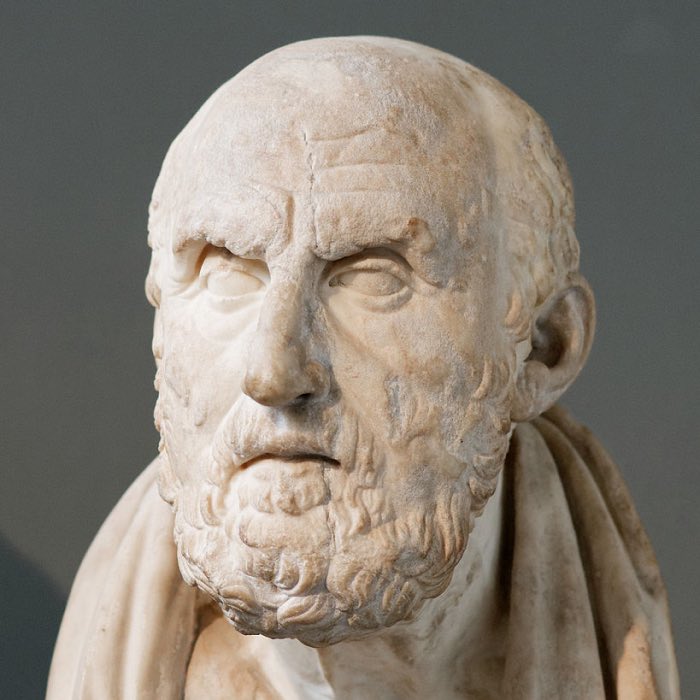

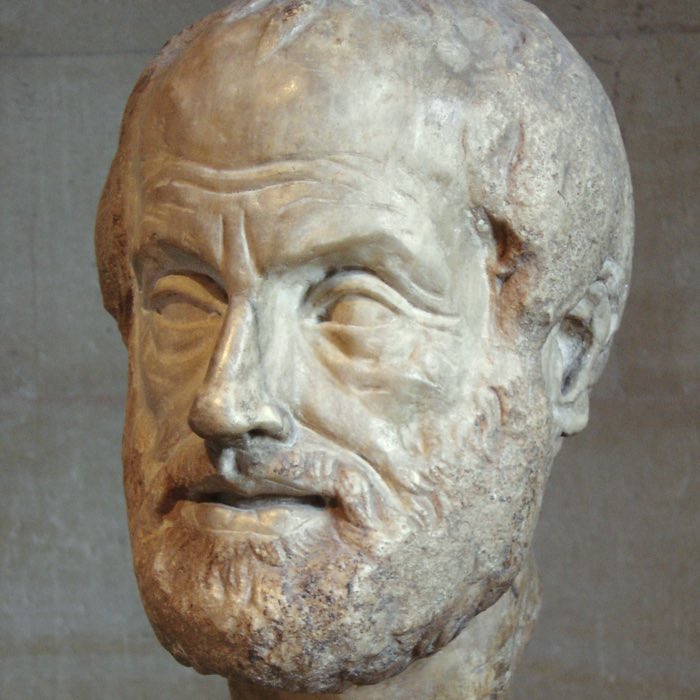

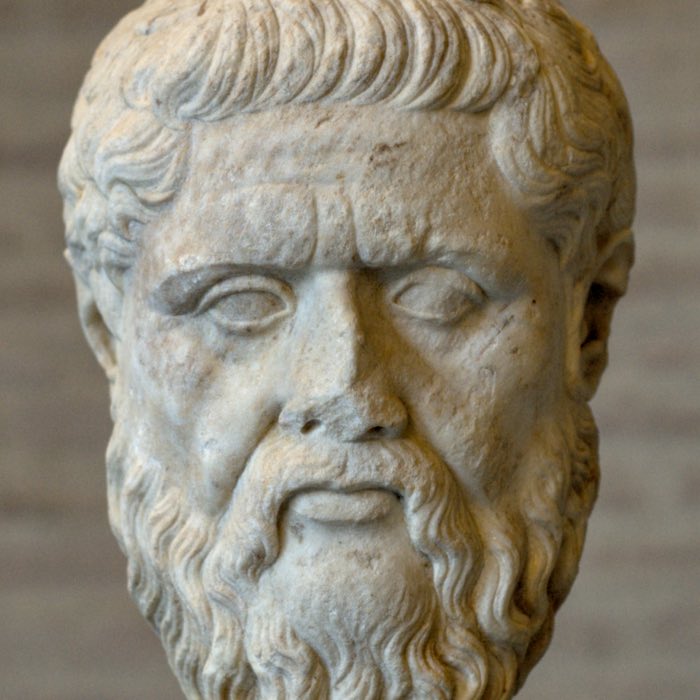

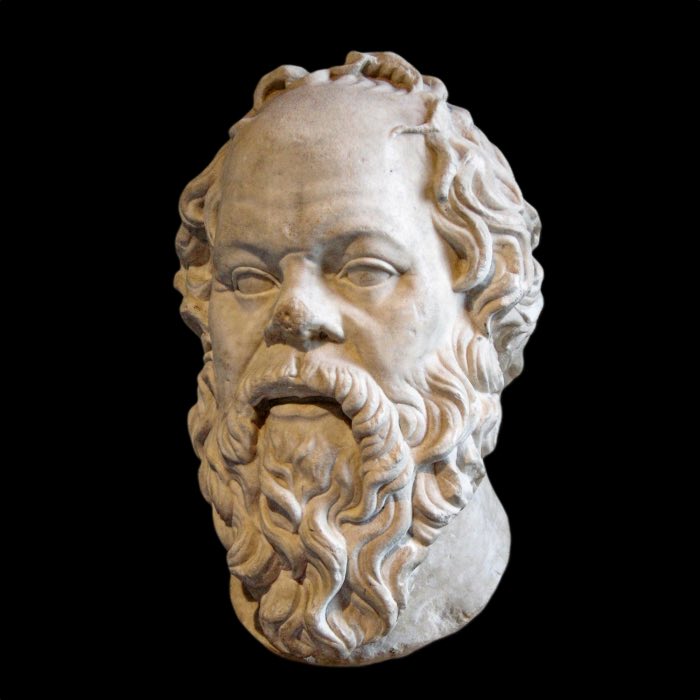

Classical Greek philosophy reached its peak with Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, who developed comprehensive systems of ethics, politics, metaphysics, and epistemology. Socratic philosophy emphasized ethical inquiry and the pursuit of virtue, while Plato and Aristotle explored the nature of reality, knowledge, and the ideal state.

Later, Hellenistic schools such as Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Skepticism shifted focus toward personal ethics and the question of how to live a good life in a changing world.

Key phases of Greek philosophy:

- Pre-Socratic phase: Focus on natural philosophy and metaphysics.

- Classical phase: Socratic ethical inquiry, Platonic idealism, and Aristotelian empiricism.

- Hellenistic phase: Emphasis on ethics and personal well-being.

Indian philosophy

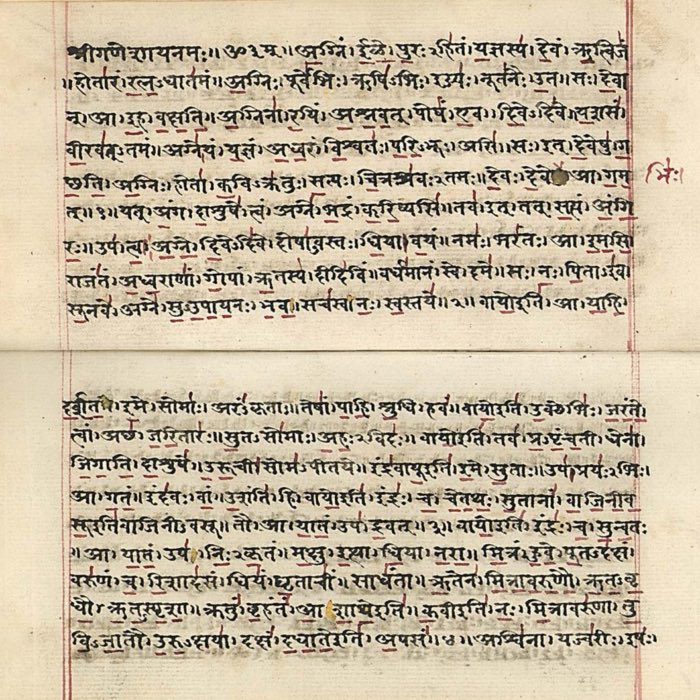

Indian philosophy also began in the 6th century BCE or earlier, with the Vedic tradition forming its earliest foundation. The Upanishads (circa 800–300 BCE) marked a transition from ritualistic Vedic religion to philosophical inquiry, focusing on metaphysical concepts such as brahman (ultimate reality) and ātman) (self).

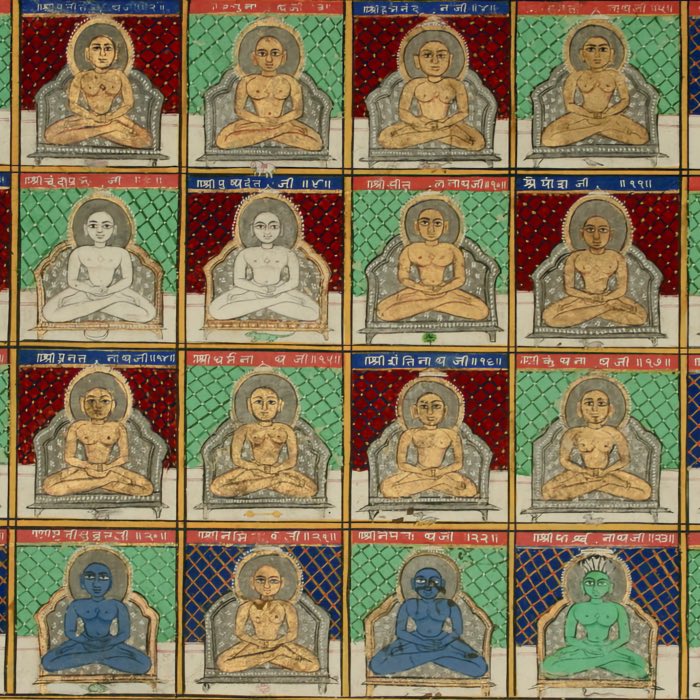

Parallel to the Vedic tradition, the Śramaṇa movement gave rise to Jainism, Buddhism, and other non-Vedic schools, which rejected Vedic authority and proposed alternative paths to liberation. Over time, Indian philosophy evolved into various schools (darśanas), each offering distinct perspectives on metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics.

Key phases of Indian philosophy:

- Vedic and Upanishadic phase: Emphasis on cosmic order, ritual, and metaphysical inquiry.

- Śramaṇa phase: Rise of heterodox schools challenging Vedic orthodoxy.

- Classical phase: Systematization of philosophical schools (e.g., Sāṃkhya, Yoga, Vedanta, Nyāya).

Metaphysical assumptions

Greek philosophy: Naturalism and rationalism

Greek philosophy, especially in its early stages, was characterized by naturalism — the attempt to explain the world through natural causes rather than supernatural myths. Pre-Socratic thinkers like Thales and Democritus proposed that all things could be reduced to a fundamental substance (e.g., water, atoms), while Heraclitus and Parmenides explored the nature of change and permanence.

Plato introduced idealism, positing that the ultimate reality consists of eternal forms or ideas, of which the material world is merely a reflection. In contrast, Aristotle developed a more empirical approach, asserting that reality consists of substances composed of form and matter.

Key metaphysical themes in Greek philosophy:

- Naturalism: Early focus on explaining the world through observable phenomena.

- Idealism: Plato’s theory of forms as eternal, unchanging realities.

- Empiricism: Aristotle’s focus on the material world and the role of observation in knowledge.

Indian philosophy: Spiritual monism and dualism

Indian philosophy is deeply rooted in spiritual monism and dualism. The Vedas introduced the idea of a single, unchanging reality (*brahman*) underlying the changing world, which was later developed by Vedanta into non-dualistic (advaita) metaphysics. In contrast, Sāṃkhya proposed a dualistic framework, distinguishing between *puruṣa (consciousness) and prakṛti (matter).

Heterodox schools like Buddhism and Jainism rejected the notion of a permanent self (ātman)), emphasizing impermanence (anicca) and the plurality of perspectives (anekāntavāda in Jainism).

Key metaphysical themes in Indian philosophy:

- Monism: The idea of an ultimate, unified reality (brahman).

- Dualism: Distinction between consciousness (puruṣa) and matter (prakṛti) in Sāṃkhya-Yoga.

- Non-self: The Buddhist doctrine of anatta (non-self) and the emphasis on impermanence.

Epistemology

Greek philosophy: Reason and empirical observation

Greek philosophers placed a strong emphasis on reason (logos) as the primary means of acquiring knowledge. Socrates’ dialectical method involved questioning assumptions to arrive at truth, while Plato emphasized rational insight into the world of forms. Aristotle developed a systematic approach to knowledge based on empirical observation and logical deduction.

Greek epistemology also explored skepticism, with Pyrrhonian Skepticism questioning the possibility of certain knowledge.

Key epistemological approaches in Greek philosophy:

- Rationalism: Plato’s belief in the primacy of reason.

- Empiricism: Aristotle’s emphasis on observation and experience.

- Skepticism: Doubt about the possibility of absolute knowledge.

Indian philosophy: Perception, inference, and meditation

Indian philosophy recognized multiple valid means of knowledge (pramāṇas), including:

- Perception (pratyakṣa): Direct sensory experience.

- Inference (anumāna): Logical reasoning based on observed patterns.

- Scriptural testimony (śabda): Knowledge derived from authoritative texts (accepted by orthodox schools).

In addition to these, Indian schools emphasized meditation and direct experience as essential for attaining higher knowledge, especially in the context of self-realization and liberation.

Key epistemological approaches in Indian philosophy:

- Pluralism: Recognition of multiple valid means of knowledge.

- Meditation: Direct experience as a means of attaining spiritual insight.

- Empirical inquiry: Emphasis on observation in schools like Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika.

Ethics and the path to liberation

Greek philosophy: Virtue and the good life

Greek ethics focused on the question of how to live a good life. Socrates emphasized the cultivation of virtue (aretē) and the examined life, while Plato linked ethics to the realization of eternal forms, particularly the form of the good. Aristotle developed a comprehensive ethical system based on the concept of eudaimonia (flourishing or well-being), achieved through the practice of virtue in accordance with reason.

Hellenistic schools like Stoicism and Epicureanism offered practical approaches to achieving tranquility and freedom from suffering in a chaotic world.

Key ethical themes in Greek philosophy:

- Virtue ethics: The cultivation of moral character as the path to the good life.

- Eudaimonia: The ultimate goal of human life, often translated as happiness or flourishing.

- Stoicism: Emphasis on self-control and acceptance of fate.

Indian philosophy: Dharma and liberation

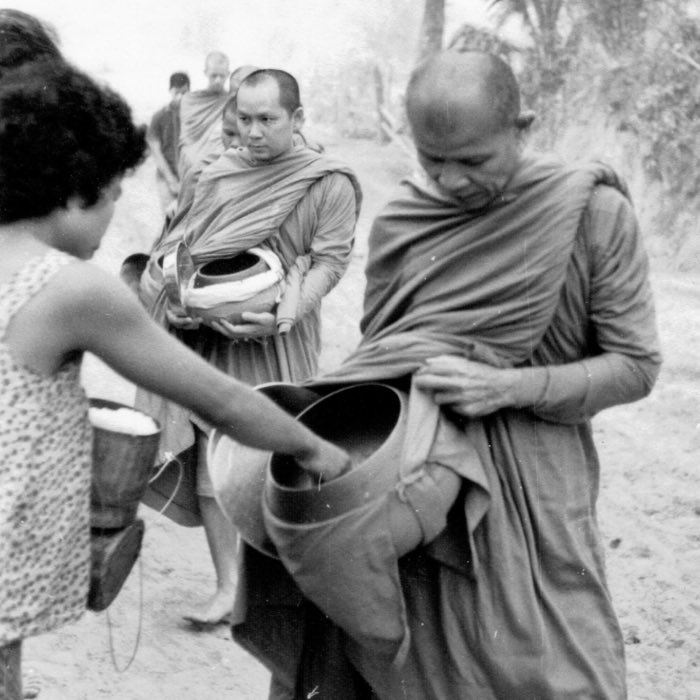

Indian ethics is deeply intertwined with the concept of dharma (duty or moral law), which varies according to one’s role in society. While the Vedic tradition emphasized the performance of one’s duties as a means to sustain cosmic order, the Śramaṇa traditions focused on personal liberation (mokṣa) through ethical conduct, meditation, and self-discipline.

Buddhism and Jainism developed detailed ethical frameworks emphasizing non-violence (ahiṃsā), compassion, and detachment from desire as essential for liberation from suffering.

Key ethical themes in Indian philosophy:

- Dharma: Moral law and duty, central to Hindu ethics.

- Ahiṃsā: Non-violence, a core principle in Jainism and Buddhism.

- Mokṣa: Liberation from the cycle of rebirth as the ultimate goal.

Conclusion

Greek and Indian philosophies, though developing independently in different cultural contexts, both sought to answer fundamental questions about existence, knowledge, and the good life. Greek philosophy emphasized reason, empirical inquiry, and virtue, while Indian philosophy placed greater emphasis on metaphysical inquiry, spiritual experience, and liberation. Despite their differences, both traditions have profoundly influenced global thought and continue to offer valuable insights into the human condition.

References and further reading

- Hellmut Flashar, Michael Erler, Günter Gawlick, Woldemar Görler, Peter Steinmetz, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd.4. Die hellenistische Philosophie, 1994, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796509308

- Green, P., Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age, 1993, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520083493

- Tarn, W. W., The Greeks in Bactria and India, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1108009416

- Pollitt, J. J., Art in the Hellenistic Age, 1986, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521276726

- Fraser, P. M., Ptolemaic Alexandria, 1985, Clarendon Press, ISBN: not 978-0198142782

- Boardman, J., The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity, 2023, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691252834

- John Boardman, The Greeks in Asia, 2015, National Geographic Books, ISBN: 9780500252130

- Christopher I. Beckwith, Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia, 2015, Princeton University Press, ISBN 10: 0691166447

- Thomas C. McEvilley, The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies, 2001, Allworth, ISBN: 978-1581152036

- William Woodthorpe Tarn, Hellenistic Civilization, 1961, Book, Penguin Books Ltd, pages 372, ISBN: 9780452008151

- Rafi U. Samad, The Grandeur Of Gandhara - The Ancient Buddhist Civilization Of The Swat, Peshawar, Kabul And Indus Valleys, 2011, Algora Publishing, ISBN: 9780875868608

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Indian philosophy, vol. 1, 2018, FB&C LTD, ISBN: 978-0331594577

- M. Hiriyanna, Essentials of Indian philosophy, 1995, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120813045

- Chandradhar Sharma, A critical survey of Indian philosophy, 2000, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120803657

- Gethin, R., The Foundations of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192892232

- Johannes Bronkhorst, Greater Magadha: Studies in the culture of early India, 2024, Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House, ISBN: 978-9359663975

- R. Puligandla, Fundamentals of Indian philosophy, 1997, D.K. Printworld, ISBN: 978-8124600863

comments