Greek and Chinese philosophy: A comparative analysis

Greek and Chinese philosophy, two of the most influential intellectual traditions in world history, emerged independently in distinct cultural and geographical contexts. Despite their separate origins, both traditions formed the intellectual backbone of their civilizations, fostering growth, prosperity, and a shared cultural identity. They tackled fundamental questions concerning human existence, ethics, politics, and the nature of the cosmos. While Greek philosophy is renowned for its analytical and speculative nature, Chinese philosophy emphasizes practical wisdom and harmonious living. After exploring both traditions in separate post series, this post examines the development, core themes, and characteristics of these two philosophical traditions, highlighting their similarities and unique contributions to human thought.

Composite image of the Greek letter “Phi” and a bagua symbol, representing Greek and Chinese philosophy. Bagua is a set of symbols intended to illustrate the nature of reality as being composed of mutually opposing forces reinforcing one another. It is a group of trigrams — composed of three lines, each either “broken” or “unbroken”, which represent yin and yang, respectively. In the center of the bagua is the taiji symbol, another representation of the concept of yin and yang. Source of the bagua symbol: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Historical development of Greek and Chinese philosophy

Greek philosophy

Greek philosophy began in the 6th century BCE in the Ionian cities of Asia Minor with the so-called Pre-Socratic philosophers, such as Thales, Anaximander, and Heraclitus. These early thinkers were primarily concerned with understanding the nature of the cosmos (physis) and sought to explain natural phenomena through rational inquiry rather than mythological narratives.

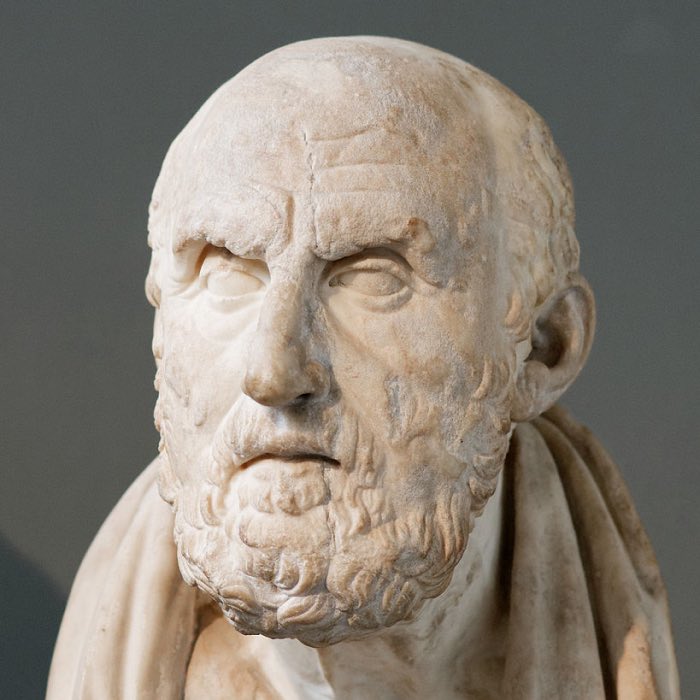

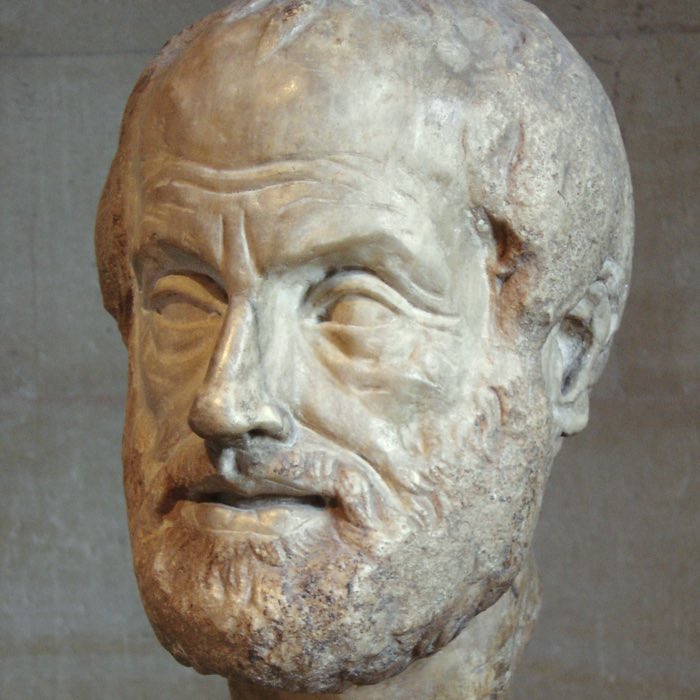

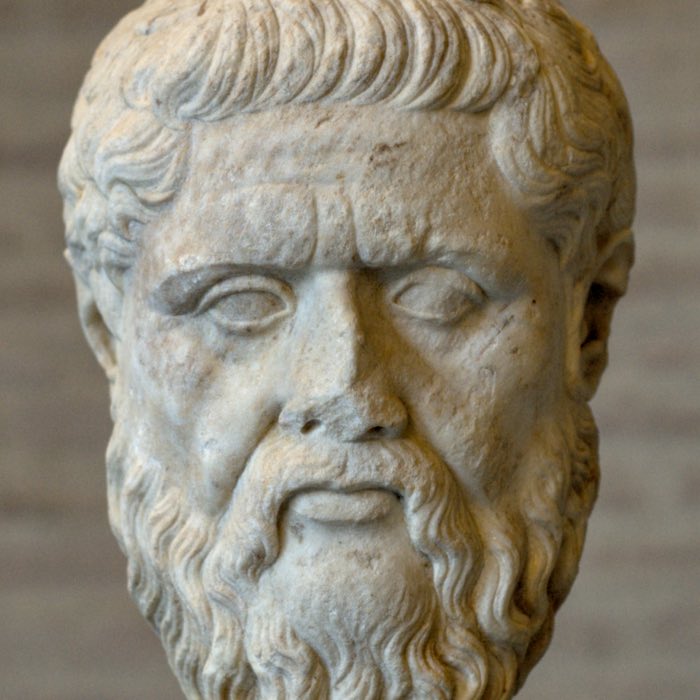

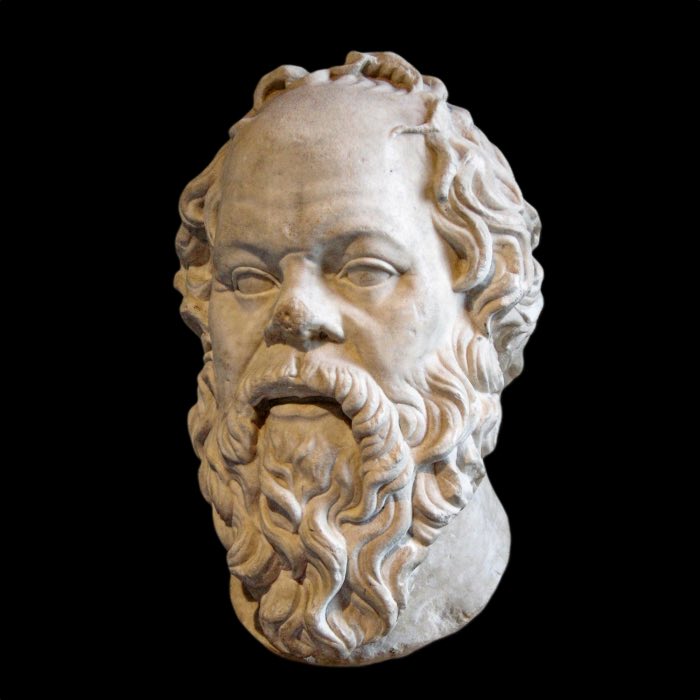

The classical period (5th–4th century BCE) witnessed the rise of three major figures: Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Socratic philosophy focused on ethical questions and the nature of virtue, while Plato’s work emphasized metaphysical speculation and the theory of forms. Aristotle, in contrast, developed a comprehensive system of logic, ethics, metaphysics, and natural science, laying the foundation for Western intellectual thought.

The Hellenistic period (4th–1st century BCE) saw the emergence of philosophical schools such as Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Skepticism, which were concerned with practical ethics and the pursuit of a good life amidst political turmoil.

Chinese philosophy

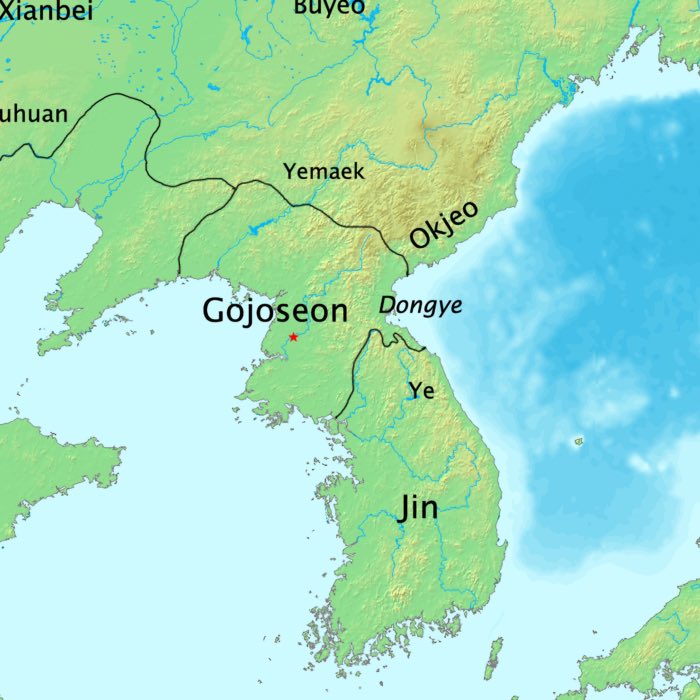

Chinese philosophy emerged during the late Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE), particularly during the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period. This era of political fragmentation and social upheaval gave rise to the “Hundred Schools of Thought”, a flourishing of intellectual activity aimed at restoring social harmony and order.

The three most prominent schools of thought were:

- Confucianism: Founded by Confucius (551–479 BCE), it emphasized morality, social harmony, and proper conduct in human relationships.

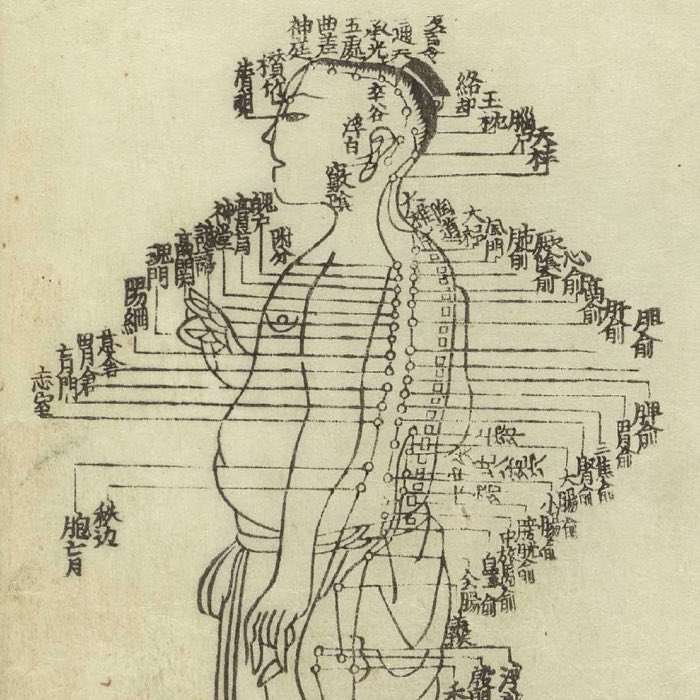

- Daoism: Attributed to Laozi and Zhuangzi, Daoism advocated for living in harmony with the Dao (the Way) through simplicity, spontaneity, and non-attachment.

- Legalism: Legalism, associated with thinkers such as Han Feizi, focused on strict laws and harsh punishments as the means to maintain social order.

Unlike Greek philosophy, which fragmented into various independent schools, Chinese philosophy often evolved through synthesis and integration. A significant example of this synthesis is the incorporation of Buddhism, which entered China during the Han dynasty and profoundly influenced Chinese thought. Over time, Chinese Buddhism adapted to local cultural and philosophical traditions, resulting in distinct schools such as Chán (Zen) Buddhism, which emphasized meditation and direct experience. The interaction between Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism eventually led to the development of Neo-Confucianism, a major intellectual movement during the Song dynasty that sought to harmonize these three traditions into a cohesive worldview. For example, Confucianism absorbed elements of Daoism and Buddhism during the later imperial period, resulting in Neo-Confucianism.

Key characteristics of Greek and Chinese philosophy

Metaphysics and cosmology

Greek philosophy is known for its speculative metaphysical inquiries. Plato’s theory of forms posits a realm of ideal, unchanging forms or essences that underlie the physical world. Aristotle, on the other hand, rejected Plato’s dualism and proposed a more empirically grounded metaphysics, focusing on substance, causality, and the nature of being (ontology).

In contrast, Chinese philosophy is generally less concerned with abstract metaphysics and more focused on cosmology and the natural order. Daoist thought emphasizes the Dao as the fundamental principle underlying the cosmos, characterized by constant change and spontaneity. In Confucianism, metaphysical speculation is subordinate to ethical and social concerns, with an emphasis on understanding the natural order (Tian, or Heaven) and human relationships.

Both traditions, however, share a common interest in understanding the principles that govern the universe. While Greek philosophers sought universal laws through reason and logic, Chinese thinkers emphasized observing natural patterns and aligning human behavior with these patterns.

Ethics and human nature

Ethical inquiry is central to both Greek and Chinese philosophy, though their approaches differ significantly.

In Greek philosophy, ethical thought often revolves around the question of what constitutes a good life (eudaimonia). Socrates emphasized self-knowledge and virtue as the keys to a well-lived life. Plato proposed that justice and the pursuit of the highest good lead to human flourishing, while Aristotle developed a virtue ethics based on cultivating moral character and living according to reason.

Chinese philosophy, particularly Confucianism, places a strong emphasis on social ethics and the cultivation of virtue within the context of human relationships. The Confucian concept of ren (benevolence) and li (ritual propriety) underscores the importance of moral conduct in maintaining social harmony. Daoist ethics, in contrast, advocate for wu wei (effortless action) and living in accordance with the natural flow of the Dao.

Greek ethics often emphasize individual reasoning and the cultivation of intellectual virtues, while Chinese ethics prioritize relational virtues and social responsibility.

Political philosophy

Greek political philosophy, particularly in the works of Plato and Aristotle, explores the nature of justice, the ideal state, and the role of citizens. Plato’s Republic outlines an ideal society governed by philosopher-kings, while Aristotle’s Politics examines different forms of government and argues for a constitutional polity as the best practical system.

Chinese political philosophy, on the other hand, focuses on maintaining order and harmony through moral leadership and proper governance. Confucius advocated for a ruler who leads by moral example, while Legalists like Han Feizi emphasized the necessity of strong laws and centralized authority to control human selfishness.

Despite these differences, both traditions share the belief that good governance depends on the moral character of rulers and the proper organization of society.

Epistemology and methodology

Greek philosophy is notable for its development of formal logic and systematic methods of inquiry. Aristotle’s Organon laid the groundwork for deductive reasoning, while the Socratic method involves dialectical questioning to arrive at truth. Greek philosophers were also pioneers in natural philosophy, laying the foundations for Western science.

In contrast, Chinese philosophy employs a more intuitive and holistic approach. Confucianism emphasizes learning through experience, reflection, and the study of classical texts, while Daoism values intuitive wisdom and direct understanding of the Dao. Rather than focusing on abstract theorizing, Chinese thought often emphasizes practical wisdom and the cultivation of character.

Similarities between Greek and Chinese philosophy

Despite their differences, Greek and Chinese philosophies share several commonalities:

- Focus on ethics: Both traditions prioritize ethical questions and the pursuit of a good life, whether through individual virtue or social harmony.

- Concern with order: Greek and Chinese thinkers alike sought to understand and establish order, whether in the cosmos, society, or the individual.

- Role of education: Both traditions emphasize the importance of education in cultivating moral and intellectual virtues.

- Holistic worldview: While Greek philosophy seeks to understand the world through reason and logic, and Chinese philosophy through harmony with natural patterns, both traditions offer holistic frameworks for understanding life and existence.

Influence and legacy

Greek philosophy has had a profound impact on Western thought, influencing fields as diverse as science, politics, ethics, and metaphysics. Its emphasis on reason, inquiry, and critical thinking laid the foundations for the development of modern philosophy and science.

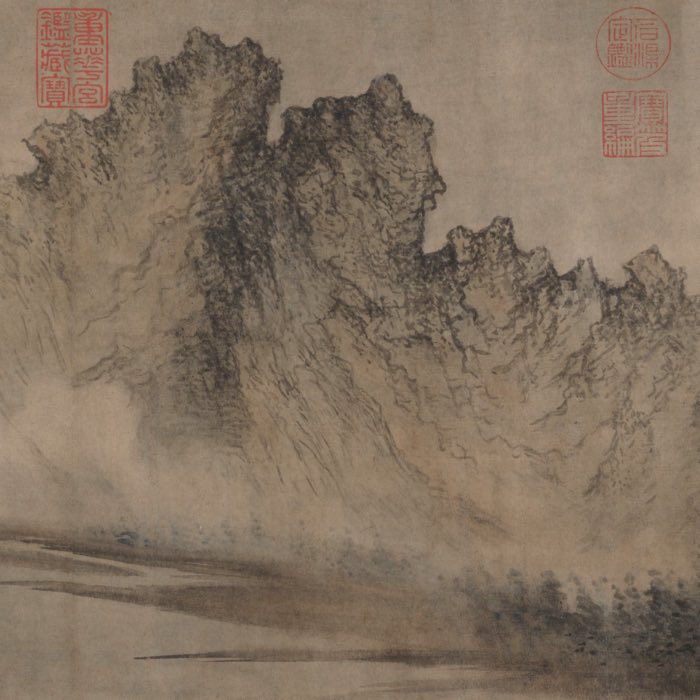

Chinese philosophy, with its emphasis on ethics, social harmony, and the natural order, has deeply shaped East Asian cultures and societies. Confucianism remains a central influence in China, Korea, and Japan, while Daoism has contributed to Chinese medicine, martial arts, and aesthetics.

Conclusion

Greek and Chinese philosophies represent two rich intellectual traditions that, despite their distinct approaches, share common concerns with ethics, order, and the nature of existence. Greek philosophy, with its analytical rigor and speculative depth, laid the groundwork for Western intellectual thought, emphasizing rational inquiry, speculative reasoning, and the search for universal principles. In contrast, Chinese philosophy, rooted in Daoism, Confucianism, and later Buddhism, prioritized practical wisdom, social harmony, and alignment with natural order. The synthesis of these schools of thought, particularly evident in Neo-Confucianism, highlights the integrative nature of Chinese intellectual history.

Despite differences in methodology, both traditions made significant contributions to the development of ethical frameworks, political theories, and approaches to knowledge. While Greek philosophy focused on intellectual virtues and speculative inquiry, Chinese philosophy emphasized relational ethics and social responsibility. Both traditions developed separately, finding individual intellectual ways to answer fundamental questions. Although their approaches differ, both successfully provided a solid foundation for their distinctive cultures and identities, demonstrating that there is not only one way to interpret the world.

To summarize, I think that studying and comparing philosophical systems from different cultures can actually broaden one’s perspective and promote a deeper understanding of different intellectual traditions and their influence on human history, as well as enrich your own worldview.

References and further reading

- Hellmut Flashar, Michael Erler, Günter Gawlick, Woldemar Görler, Peter Steinmetz, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd.4. Die hellenistische Philosophie, 1994, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796509308

- Green, P., Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age, 1993, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520083493

- Tarn, W. W., The Greeks in Bactria and India, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1108009416

- Pollitt, J. J., Art in the Hellenistic Age, 1986, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521276726

- Fraser, P. M., Ptolemaic Alexandria, 1985, Clarendon Press, ISBN: not 978-0198142782

- Boardman, J., The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity, 2023, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691252834

- John Boardman, The Greeks in Asia, 2015, National Geographic Books, ISBN: 9780500252130

- Christopher I. Beckwith, Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia, 2015, Princeton University Press, ISBN 10: 0691166447

- Thomas C. McEvilley, The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies, 2001, Allworth, ISBN: 978-1581152036

- William Woodthorpe Tarn, Hellenistic Civilization, 1961, Book, Penguin Books Ltd, pages 372, ISBN: 9780452008151

- Rafi U. Samad, The Grandeur Of Gandhara - The Ancient Buddhist Civilization Of The Swat, Peshawar, Kabul And Indus Valleys, 2011, Algora Publishing, ISBN: 9780875868608

- Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), I Ging: das Buch der Wandlungen, 2017, Nikol Verlag, ISBN: 9783868203950

- Laozi, Viktor Kalinke (Übersetzung), Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing, Bd. 1: Eine Wiedergabe seines Deutungsspektrums: Text, Übersetzung, Zeichenlexikon und Konkordanz, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015159

- Viktor Kalinke, Laozi, Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing, Bd. 2: Eine Erkundung seines Deutungsspektrums: Anmerkungen und Kommentare, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015180

- Viktor Kalinke, Nichtstun als Handlungsmaxime: Studien zu Laozi Daodejing, Bd. 3: Essay zur Rationalität des Mystischen, 2011, Leipziger Literaturverlag, ISBN: 9783866601154

- Laozi, Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), Tao te king - das Buch des alten Meisters vom Sinn und Leben, 2010, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783866474659

- Zhuangzi, Viktor Kalinke (Translator), Zhuangzi - Das Buch der daoistischen Weisheit, 2019, Reclam, ISBN: 9783150112397

- Lü Bu We (Autor), Richard Wilhelm (Herausgeber, Übersetzer), Das Weisheitsbuch der alten Chinesen - Frühling und Herbst des Lü Bu We, 2015, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783730602133

- Bokenkamp, Stephen R., Early Daoist scriptures, 1999, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520219311

- Kohn, Livia, Daoism and Chinese culture, 2005, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-1931483001

- Robinet, Isabelle, Daoism: Growth of a religion, 1997, Stanford University Press, ISBN: 978-0804728386

- Watson, Burton (trans.), The complete works of Zhuangzi, 2013, Columbia University Press, ISBN: 978-0231164740

- Martin Bödicker, Schrittweise das Dao Verwirklichen - Tianyinzi - Tägliche Übung - Riyong, 2015, Verlag n/a, ISBN: 9781512157475

- Martin Bödicker, Innere Übung - Neiye - Das Dao als Quelle - Yuandao, 2014, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, ISBN: 978-1503157071

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Michael S Diener (Herausgeber), Franz K Erhard (Herausgeber), Kurt Friedrichs (Herausgeber), Lexikon der östlichen Weisheitslehren - Buddhismus, Hinduismus, Daoismus, Zen, 1986, O.W. Barth, ISBN: 9783502674047

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Das Lexikon des Daoismus - Grundbegriffe und Lehrsysteme; Meister und Schulen; Literatur und Kunst; meditative Praktiken; Mystik und Geschichte der Weisheitslehre von ihren Anfängen bis heute, 1996, Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, ISBN: 9783442126644

- Augustin, Birgitta, “Daoism and Daoist Art””, 2000, In: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, linkꜛ

comments