The systematic philosophy of Plato and Aristotle: Foundations of Western thought

The systematic philosophies of Plato and Aristotle represent a defining moment in the history of Western intellectual tradition. Emerging from the Athenian golden age of the 4th century BCE, these two thinkers built upon the inquiries of their predecessors, particularly Socrates, to create comprehensive frameworks addressing the fundamental questions of existence, knowledge, ethics, and politics. Together, Plato and Aristotle laid the groundwork for disciplines as diverse as metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, aesthetics, and the natural sciences.

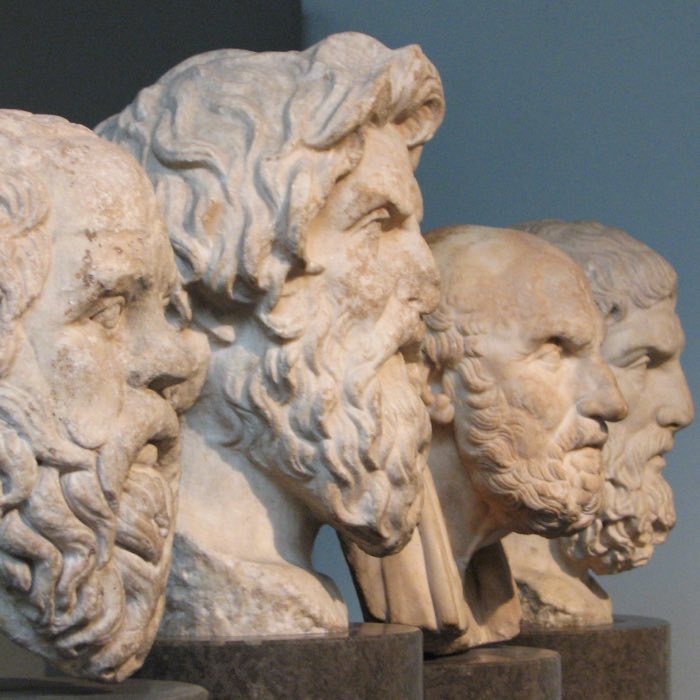

Plato’s Academy, mosaic floor in Pompeii, 1st century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The legacy of Socrates and the turn to systematic philosophy

Both Plato and Aristotle were profoundly influenced by Socrates, whose ethical inquiries and dialectical method inspired a generation of thinkers to engage in critical and reflective thought. Socrates’ emphasis on moral virtue, intellectual humility, and the pursuit of wisdom provided the foundation for much of Plato’s and Aristotle’s work. However, the trial and execution of Socrates in 399 BCE also highlighted the limitations of Athenian democracy and the need for a deeper understanding of justice, governance, and human flourishing.

Plato, a student of Socrates, sought to preserve and extend his teacher’s insights through a systematic exploration of the principles underlying human and cosmic order. Aristotle, Plato’s most renowned student, built upon and often challenged his teacher’s ideas, developing a comprehensive system that integrated empirical observation with rigorous logical analysis. Together, their works represent the transition from the fragmentary and exploratory approaches of earlier philosophy to a unified and systematic vision of the world.

Plato: The idealist vision

Plato’s philosophy is characterized by its emphasis on the realm of eternal and unchanging forms, which he regarded as the true reality underlying the mutable world of sense perception. According to Plato, the forms are abstract, perfect, and universal entities that exist independently of the material world. They are the objects of true knowledge (episteme), which can only be attained through reason and intellectual insight.

The most famous expression of Plato’s theory of forms appears in his Republic, particularly in the allegory of the cave. Here, Plato depicts human beings as prisoners in a cave, mistaking shadows on a wall for reality. The philosopher, through reason and education, escapes the cave and ascends to the realm of the forms, attaining knowledge of the true nature of justice, beauty, and the good.

Plato’s systematic philosophy encompasses a wide range of disciplines, including:

- Metaphysics: The study of the forms and their relationship to the material world.

- Epistemology: The distinction between knowledge (episteme) and opinion (doxa), emphasizing the role of reason in apprehending eternal truths.

- Ethics: The pursuit of the good life through the cultivation of virtue and alignment with the forms.

- Politics: The ideal state as a reflection of the order and harmony of the forms, governed by philosopher-kings who possess true knowledge.

- Aesthetics: The role of art and beauty in reflecting and inspiring the soul’s ascent toward the forms.

Plato’s dialogues, written in the form of dramatic conversations, illustrate his dialectical method and his commitment to exploring the complexity of philosophical questions. His Academy, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world, became a center for intellectual innovation and the dissemination of his ideas.

Aristotle: The empirical framework

Aristotle, a student of Plato, developed a systematic philosophy that diverged significantly from his teacher’s idealism. While Plato emphasized the realm of forms, Aristotle focused on the material and natural world, seeking to understand the principles governing change, causation, and the diversity of phenomena. For Aristotle, knowledge begins with empirical observation and proceeds through logical analysis to uncover the causes and purposes of things.

Aristotle’s philosophy is distinguished by its emphasis on teleology — the study of purpose and final causes. He argued that everything in nature has a purpose or end (telos), which provides the key to understanding its nature and function. This teleological approach underpins his investigations in a wide range of disciplines, including:

- Metaphysics: The study of being (ontology) and the principles of substance, causation, and change. Aristotle rejected Plato’s theory of forms, instead positing that forms exist within individual substances as their essential nature.

- Natural philosophy: The systematic study of the natural world, including biology, physics, and cosmology. Aristotle’s observations and classifications of living organisms laid the groundwork for the biological sciences.

- Logic: The development of formal logic, including the syllogism, as a tool for rigorous reasoning and argumentation. Aristotle’s Organon remains a foundational text in the study of logic.

- Ethics: The pursuit of the good life through the cultivation of virtue and the realization of human potential. In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle defines happiness (eudaimonia) as the fulfillment of one’s rational and moral capacities.

- Politics: The study of human communities and the principles of just governance. Aristotle argued that the polis exists to promote the virtuous life, emphasizing the interdependence of individual and collective flourishing.

- Aesthetics: The analysis of art and tragedy, particularly in his Poetics, where he explores the cathartic and educational functions of literature and drama.

Aristotle’s Lyceum, a research and teaching institution, served as a hub for empirical and philosophical inquiry, producing works that influenced disciplines as varied as zoology, ethics, and political theory.

Shared contributions and divergent approaches

Despite their differences, Plato and Aristotle share several key contributions to the development of systematic philosophy. Both sought to integrate diverse fields of inquiry into coherent frameworks, emphasizing the interconnectedness of metaphysics, ethics, and politics. They also shared a commitment to rational inquiry as the foundation for understanding and improving the human condition.

However, their approaches reflect fundamental philosophical differences. Plato’s emphasis on transcendent forms and the primacy of reason aligns with an idealist worldview, while Aristotle’s focus on empirical observation and the immanence of forms reflects a naturalistic and practical orientation. These differences have shaped the trajectory of Western thought, with Plato inspiring traditions of metaphysical idealism and Aristotle influencing the empirical sciences and practical ethics.

The legacy of systematic philosophy

The systematic philosophies of Plato and Aristotle have had an enduring impact on Western thought, shaping fields as diverse as metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, politics, and the natural sciences. Their works served as the foundation for medieval scholasticism, Renaissance humanism, and the Enlightenment, influencing thinkers such as Augustine, Aquinas, Descartes, Kant, and Hegel.

In contemporary philosophy, the ideas of Plato and Aristotle continue to inspire debates about the nature of reality, the limits of human knowledge, and the principles of ethical and political life. Their emphasis on systematic thought, rigorous reasoning, and the pursuit of wisdom remains a guiding ideal for intellectual inquiry and human flourishing.

Conclusion

The systematic philosophies of Plato and Aristotle represent a pinnacle of intellectual achievement in ancient Greece, offering comprehensive frameworks for understanding the cosmos, human nature, and the pursuit of the good life. While their approaches differ in fundamental ways, their shared commitment to rational inquiry and the integration of diverse fields of knowledge established the foundations for Western philosophy and science. Their influence attests to the power of systematic thought to illuminate the complexities of existence and guide the human quest for truth and meaning.

References and further reading

- Michael Erler, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 2/2. Platon, 2007, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 978-3-7965-2237-6

- Hellmut Flashar, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 3. Ältere Akademie, Aristoteles, Peripatos, 2004, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 978-3-7965-1998-7

- David Ebrey, The Cambridge Companion to Plato, 2022, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1108457262

comments