Stoicism: Philosophy of reason, virtue, and tranquility

Stoicism, founded by Zeno of Citium in the early 3rd century BCE, represents one of the most enduring and influential schools of philosophy in Western thought. Emerging in Athens during the Hellenistic period, Stoicism evolved as a comprehensive system addressing ethics, logic, and natural philosophy. The Stoics sought to understand the principles governing the cosmos and to live in harmony with nature, emphasizing the cultivation of reason, virtue, and resilience in the face of life’s challenges. Through its emphasis on personal responsibility, emotional regulation, and the distinction between what is within and beyond our control, Stoicism provided a practical guide for achieving tranquility (ataraxia) and flourishing (eudaimonia). Its teachings profoundly influenced Roman thinkers such as Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius, and later Christian theologians who found resonance between Stoic ethics and Christian beliefs.

Portrait of Thales by Wilhelm Meyer, based on a bust from the 4th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The origins and development of Stoicism

Stoicism was born in the cosmopolitan intellectual environment of Hellenistic Athens, where Zeno of Citium began teaching around 300 BCE in the Stoa Poikilē (the Painted Porch), from which the school derives its name. Zeno, influenced by earlier thinkers such as the Cynics, Heraclitus, and the Socratic tradition, developed a philosophy that emphasized rationality, ethical living, and the unity of the cosmos.

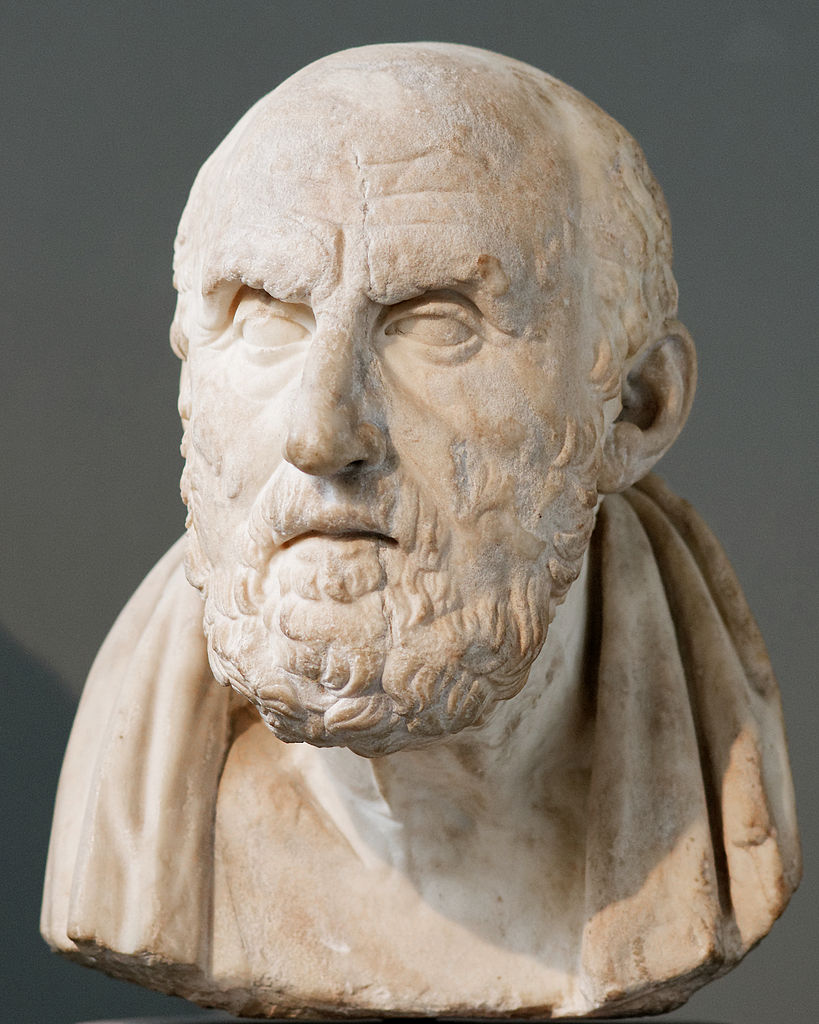

The early Stoics, including Cleanthes and Chrysippus, built upon Zeno’s teachings, creating a systematic framework that integrated ethics, logic, and physics. Chrysippus, in particular, played a pivotal role in shaping Stoic doctrine, earning him the reputation as the second founder of the school. His rigorous contributions to logic, metaphysics, and psychology established Stoicism as a cohesive and influential philosophical system.

Chrysippus, the third leader of the Stoic school, wrote over 300 books on logic. Marble, Roman copy after a lost Hellenistic original of the late 3rd century BC. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

In the Roman period, Stoicism underwent further development and popularization through the works of Seneca, a statesman and moralist; Epictetus, a former slave turned teacher; and Marcus Aurelius, a Roman emperor and philosopher. These later Stoics adapted the principles of the school to address the practical challenges of governance, personal adversity, and the pursuit of virtue in a complex and often turbulent world.

Logos and the Stoic cosmos: Living in harmony with nature

At the heart of Stoic philosophy is the principle of living in accordance with nature (kata physin). For the Stoics, nature encompasses both the rational order of the cosmos and the inherent capacities of human beings as rational agents. The universe, they argued, is governed by logos, a divine rational principle that imbues all things with purpose and coherence.

Everything in the universe unfolds according to causes and follows a predetermined plan, emphasizing the Stoic belief in determinism. While human beings possess free will, this freedom lies in their ability to act in accordance with or against the natural order. By aligning their will with the logos, individuals achieve harmony with the cosmos. This alignment requires recognizing and accepting the structure of reality, including the inevitability of change, suffering, and death. For the Stoics, the transitory nature of life serves as a reminder of what truly matters: living virtuously and cultivating resilience.

Unlike Plato’s transcendent realm of Forms or Heraclitus’ abstract rational principle, the Stoic logos was material and immanent, present within all things as a divine, structuring force. The Stoics described logos as an active, fiery pneuma (breath or spirit) that pervades the cosmos, giving it order and direction. Rather than existing apart from reality, as in Platonic thought, Stoic logos was fully embedded in nature, ensuring that everything unfolded according to rational laws.

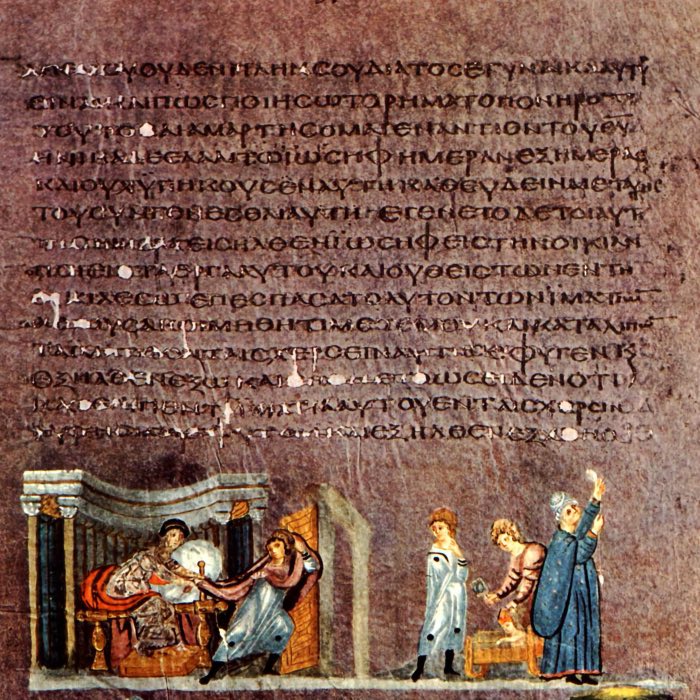

This idea extended to the concept of Logos Spermatikos, the seminal reason that operated within individual entities, guiding their growth and purpose. According to the Stoics, all things contained within them the seeds (spermatikoi logoi) of their development, reflecting the larger rational structure of the universe. Later, Christian theologians like Justin Martyr would reinterpret this concept, identifying Christ as the incarnate logos, the ultimate expression of divine rationality governing the cosmos.

Ethics: Virtue as the sole good

Stoic ethics is grounded in the belief that virtue is the only true good and the essential condition for human flourishing (eudaimonia). Unlike external goods such as wealth, health, or social status, which are subject to chance and beyond our control, virtue lies entirely within the power of the individual. It is through the cultivation of the cardinal virtues — wisdom, courage, justice, and temperance — that one achieves a life of moral excellence and contentment.

The Stoics distinguished between what is within our control (our judgments, intentions, and actions) and what is not (external events and outcomes). This distinction underpins the Stoic principle of focusing on one’s own moral agency while accepting external circumstances with equanimity. By recognizing that external events cannot harm one’s virtue, Stoics sought to cultivate resilience and freedom from destructive emotions (apatheia).

This ethical framework is exemplified in the writings of Epictetus, who emphasized that “It is not events themselves that disturb people, but their judgments about those events”. For the Stoics, the key to happiness lies in reorienting one’s perspective and maintaining a rational and virtuous disposition, regardless of external circumstances.

The role of reason

For the Stoics, rationality is both a distinguishing human capacity and a moral imperative. Humans, unlike animals, are endowed with reason, and it is their duty to cultivate and live in accordance with it. Rationality guides individuals in discerning the principles of justice, temperance, and other virtues, enabling them to make sound judgments and overcome destructive emotions, which are seen as arising from false beliefs.

Chrysippus advanced propositional logic as a way to ensure clarity and consistency in reasoning. This logical rigor supported not only their ethical philosophy but also their broader understanding of the cosmos.

Emotional resilience: The Stoic approach to the passions

One of the most distinctive aspects of Stoicism is its approach to the passions (pathē), which the Stoics regarded as irrational and destructive emotional states that disrupt the soul’s harmony. Examples include anger, fear, envy, and excessive desire. The Stoics argued that such passions result from false beliefs about what is good or bad, particularly the belief that external goods are necessary for happiness.

To achieve freedom from the passions (apatheia), the Stoics advocated for the cultivation of rational judgment and the practice of mindfulness. By examining and correcting their beliefs, individuals could reframe their emotional responses and maintain a state of inner tranquility.

Community and universalism

The Stoics emphasized the natural sociability of human beings, a concept they called “oikeiosis”. This idea reflects the innate human tendency to care for others and to act in ways that benefit the broader community. Building on this foundation, the Stoics championed a cosmopolitan vision in which all people belong to a single universal community governed by reason, i.e., by the logos. The Stoics rejected narrow notions of identity based on nationality, ethnicity, or social class, advocating instead for the recognition of shared humanity and the cultivation of justice and kindness toward all.

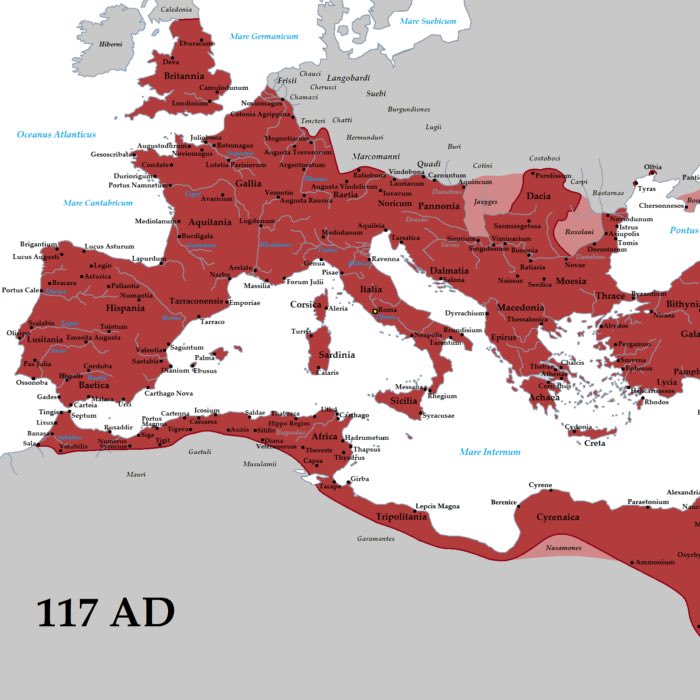

Marcus Aurelius (121-180 CE), the Stoic Roman emperor. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

This cosmopolitan ethic is reflected in the writings of Marcus Aurelius, who frequently emphasized the interconnectedness of all people and the importance of contributing to the common good. For the Stoics, living in harmony with nature also meant fulfilling one’s social and political responsibilities, promoting justice, and acting as a rational and virtuous member of the larger human community.

A bust of Seneca, a Stoic philosopher from the Roman Empire who served as an adviser to Nero. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Stoicism and Christian philosophy

The influence of Stoicism extended deeply into the development of early Christian thought, particularly in its ethical and metaphysical dimensions. Early Christian theologians, including figures like Augustine and Ambrose, found affinities between Stoic principles and Christian teachings. Stoicism’s emphasis on virtue, rationality, and the natural order resonated with the Christian vision of moral responsibility and divine providence.

Ethics and virtue

The Stoic belief that virtue is the highest good paralleled Christian ideals of moral integrity and spiritual discipline. Christian thought embraced and expanded upon the Stoic notion of controlling passions, emphasizing the cultivation of virtues like humility, patience, and charity. The concept of apatheia influenced Christian asceticism, where emotional detachment was reframed as surrendering one’s will to God.

Logos and divine order

The Stoic understanding of logos as the rational principle organizing the cosmos found a new interpretation in Christian theology. For Christians, the Logos was personified in Christ, described in the Gospel of John as the “Word” that was with God and was God. This reinterpretation allowed for a synthesis of Stoic cosmology with Christian metaphysics, bridging classical philosophy and emerging Christian doctrine.

Shared cosmopolitanism

Both Stoicism and Christianity emphasized the unity of humanity. The Stoic idea of a universal community governed by reason aligned with the Christian teaching of universal brotherhood under God. This shared perspective helped early Christian thinkers to articulate a vision of justice, compassion, and solidarity that transcended cultural and social boundaries.

Legacy in Christian practice

The Stoic influence is evident in Christian practices of contemplation, prayer, and ethical self-reflection. The meditative writings of Marcus Aurelius, for instance, found echoes in Christian monastic traditions. Furthermore, the Stoic emphasis on accepting events beyond one’s control resonated with the Christian virtue of trust in divine providence, shaping a shared ethos of resilience and spiritual focus.

Conclusion

Stoicism is a philosophy centered on reason (logos), virtue (arete), and tranquility (ataraxia), and living in harmony with nature (kata physin). Its core principles, including the cultivation of wisdom, the acceptance of what lies beyond one’s control, and the pursuit of ethical excellence, have left a profound impact on Western thought. Originating in Hellenistic Greece, Stoicism influenced Roman philosophers such as Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, shaping their approach to governance and personal ethics. In later centuries, Stoicism’s emphasis on virtue and rationality informed early Christian philosophy, with its concept of logos aligning with theological interpretations of divine order. The Stoic legacy endures as a cornerstone of ethical and metaphysical thought, bridging ancient Greek philosophy, Roman pragmatism, and Christian spiritual ideals.

References and further reading

- Hellmut Flashar, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 3. Ältere Akademie, Aristoteles, Peripatos, 2004, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 978-3-7965-1998-7

- Hellmut Flashar, Michael Erler, Günter Gawlick, Woldemar Görler, Peter Steinmetz, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd.4. Die hellenistische Philosophie, 1994, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796509308

- Stefan Dienstbeck, Die Theologie der Stoa, 2015, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, ISBN: 9783110431803

- Long, A. A., Epictetus: A Stoic and Socratic Guide to Life, 2004, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199268856

- Sellars, J., Stoicism, 2006, Routledge, ISBN: 978-1844650538

- Irvine, W. B., A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy, 2009, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195374612

- Epictetus, Handbüchlein der Moral - griechisch/deutsch, 1992, Reclam, ISBN: 9783150087886

- Mark Aurel, Des Kaisers Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Selbstbetrachtungen, 1993, Reclam, ISBN: 9783150012413

comments