Socrates: The philosopher of ethical inquiry and the search for wisdom

Socrates of Athens (469–399 BCE) is widely regarded as one of the foundational figures in Western philosophy. Unlike the pre-Socratic philosophers who primarily focused on cosmology, metaphysics, and natural philosophy, Socrates turned his attention to ethics, human behavior, and the nature of knowledge. His life and teachings marked a decisive shift in the philosophical landscape of ancient Greece, establishing a tradition of critical inquiry that prioritized moral and intellectual self-examination.

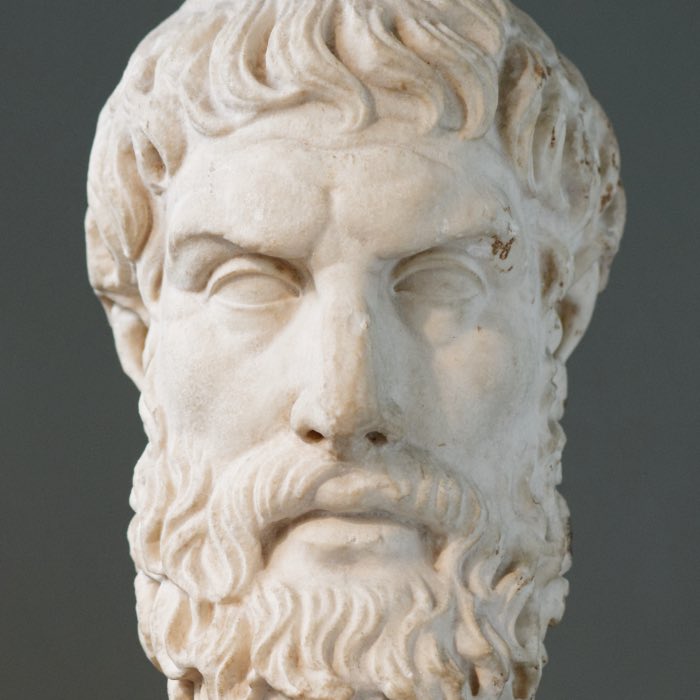

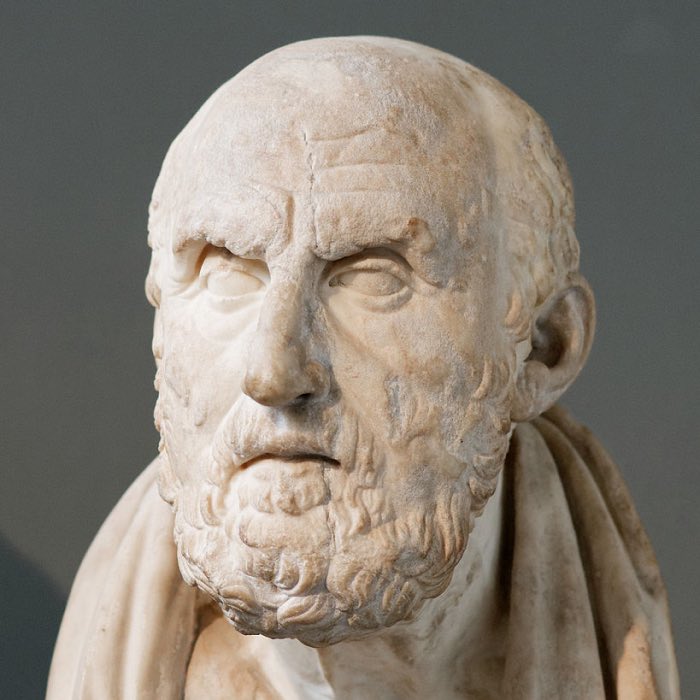

Portrait of Socrates. Marble, Roman artwork, 1st century, perhaps a copy of a lost bronze statue made by Lysippos. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The life and context of Socrates

Socrates lived during a tumultuous period in Athenian history, characterized by political instability, the rise and fall of the Athenian Empire, and the Peloponnesian War. Born into a modest family, Socrates initially worked as a stonecutter before devoting himself to philosophy. He spent much of his life in the public spaces of Athens, engaging in dialogue with a wide range of individuals, from fellow citizens and political leaders to Sophists and youth seeking guidance.

Socrates’ method of questioning, later termed the elenchus (or Socratic method), involved probing conversations aimed at uncovering contradictions, clarifying concepts, and fostering self-awareness. This approach often unsettled his interlocutors, earning him both admiration and animosity. Despite his unassuming demeanor and professed ignorance, Socrates was a polarizing figure, celebrated for his wisdom by some and criticized as a subversive influence by others.

In 399 BCE, Socrates was tried and executed on charges of corrupting the youth and impiety. His trial and death, as recorded by Plato in the Apology and other dialogues, remain among the most famous events in the history of philosophy, symbolizing the tension between free inquiry and societal norms.

The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Louis David, 1787. Socrates regularly opposed the sophists, unmasking their impostures. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Socratic turn: Ethics and the search for virtue

Socrates’ philosophy is characterized by its focus on ethical questions and the practical concerns of human life. He sought to understand the nature of virtue (aretē) and its relationship to happiness (eudaimonia), emphasizing that a good life depends on the cultivation of moral excellence and wisdom. For Socrates, virtue was not merely a matter of external actions or adherence to social conventions but an internal state of the soul, rooted in knowledge and self-awareness.

Central to Socratic ethics is the idea that no one willingly does wrong; wrongdoing arises from ignorance of what is truly good. This principle, often summarized as “virtue is knowledge”, suggests that moral education and the pursuit of wisdom are essential for ethical behavior. Socrates believed that by examining one’s beliefs and values through reasoned dialogue, individuals could achieve greater self-knowledge and align their actions with the principles of justice, courage, and temperance.

Socrates also challenged traditional notions of honor, wealth, and power, arguing that these external goods are meaningless without virtue. He famously declared in Plato’s Apology:

“The unexamined life is not worth living.”

This statement encapsulates his commitment to philosophical inquiry as a means of achieving a life of meaning and integrity.

The Socratic method: Dialogue and dialectic

The Socratic method, or elenchus, is both a pedagogical technique and a tool for philosophical investigation. It involves a process of questioning and refutation aimed at exposing inconsistencies, testing assumptions, and guiding participants toward clearer understanding and greater self-awareness. Rather than presenting definitive answers, Socrates used the elenchus to stimulate critical thinking and encourage his interlocutors to question their own beliefs.

A typical Socratic dialogue begins with Socrates asking a seemingly simple question, such as “What is justice?” or “What is courage?” His interlocutor offers a definition, which Socrates examines through a series of probing questions, often revealing contradictions or inadequacies in the response. This process forces the interlocutor to revise their initial position, deepening their understanding and highlighting the complexity of the issue.

The elenchus exemplifies Socrates’ belief in the importance of intellectual humility and the value of collaborative inquiry. By admitting his own ignorance, Socrates positioned himself as a fellow seeker of truth rather than an authoritative teacher. His method reflects a commitment to reason and dialogue as the means of discovering knowledge and fostering personal and communal growth.

Socrates and the Sophists: A Critical relationship

Socrates is often contrasted with the Sophists, itinerant teachers who were contemporaries of his and shared his interest in rhetoric, ethics, and education. While the Sophists emphasized the power of persuasion and the relativity of truth, Socrates sought objective and universal principles of justice, virtue, and knowledge. He criticized the Sophists for prioritizing success and influence over genuine wisdom, accusing them of using rhetoric to manipulate rather than enlighten.

Despite these critiques, Socrates shared some common ground with the Sophists, particularly in their focus on human affairs and their rejection of traditional mythological explanations. However, his commitment to absolute moral standards and his use of dialectical reasoning set him apart, establishing a distinctive approach to philosophy that emphasized truth and ethical integrity.

The trial and death of Socrates

Socrates’ trial and execution remain among the most enduring and debated episodes in Western philosophy. Accused of corrupting the youth and introducing new gods, Socrates defended himself with characteristic wit and defiance, asserting that he had acted in service of the city by encouraging critical thought and moral reflection. His refusal to abandon his philosophical mission, even under threat of death, exemplifies his commitment to principle and his belief in the inseparability of philosophy and life.

Plato’s account of Socrates’ final moments in the Apology, Crito, and Phaedo portrays him as a figure of remarkable courage and composure, willingly accepting his fate as a testament to the values he espoused. His death, often likened to a martyrdom for truth and reason, has inspired generations of thinkers and established Socrates as a symbol of intellectual integrity and moral resilience.

Legacy and influence

The influence of Socrates on the history of philosophy is unparalleled. His emphasis on ethical inquiry, critical dialogue, and intellectual humility shaped the philosophical traditions of both his contemporaries and later generations. Plato, Socrates’ most famous student, preserved and expanded his teacher’s ideas, using Socratic dialogue as the foundation for his own metaphysical and epistemological explorations. Aristotle, in turn, built on Socratic ethics to develop a comprehensive framework for moral philosophy.

Socrates’ commitment to reason, dialogue, and the pursuit of truth resonates in the works of countless philosophers, from the [Stoics] and early Christians to Enlightenment thinkers such as Descartes, Kant, and Hegel. His life and teachings continue to inspire contemporary debates about ethics, education, and the role of philosophy in public life.

Conclusion

Socrates stands as a transformative figure in the history of Western thought, embodying the philosophical ideals of critical inquiry, ethical self-examination, and the relentless pursuit of wisdom. His life and teachings challenged the assumptions of his time, laying the foundation for a tradition of philosophy that seeks to understand and improve the human condition. Through his method, his questions, and his unwavering commitment to virtue, Socrates remains a timeless exemplar of the philosophical life, inviting us to examine ourselves and the world with courage, humility, and integrity.

References and further reading

- Klaus Döring, Michael Erler, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 2/1. Sophistik, Sokrates, Sokratik, Mathematik, Medizin, 1998, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796510366

- Guthrie, W. K. C., Socrates, 2008, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521096676

- Brickhouse, T. C., & Smith, N. D., Plato’s Socrates, 1996, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195101119

- Waterfield, R., Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths, 2010, Faber And Faber Ltd, ISBN: 978-0571235513

comments