Skepticism and non-attachment: Philosophical parallels between Pyrrhonism and Buddhism

The intersection of Hellenistic philosophy and Indian spiritual traditions has long intrigued scholars, especially regarding the striking conceptual parallels between Pyrrhonism, subject of our previous post, and early Buddhism. Despite their distinct historical and cultural contexts, both traditions offer profound frameworks for addressing the nature of belief, perception, and human suffering. While the post about Pyrrhonism already discussed these potential connections, this post further focusses on the philosophical affinities and divergences between Pyrrhonism and Buddhism.

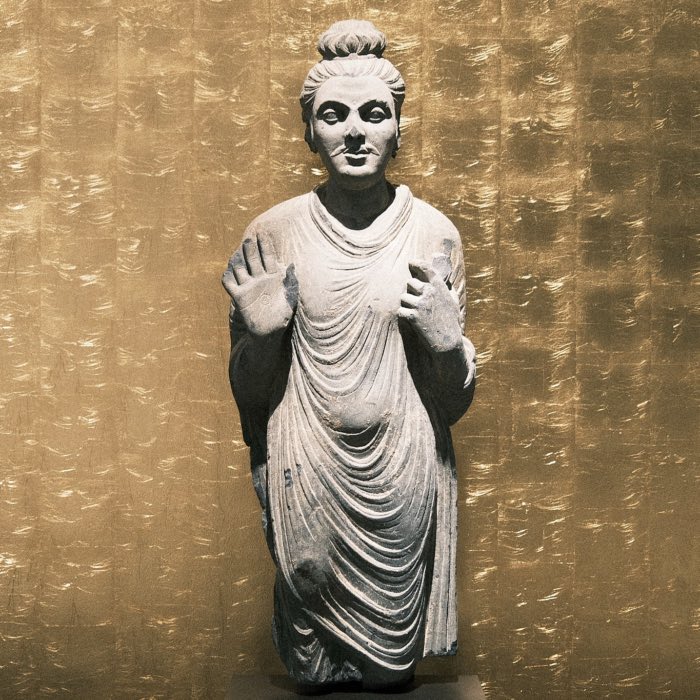

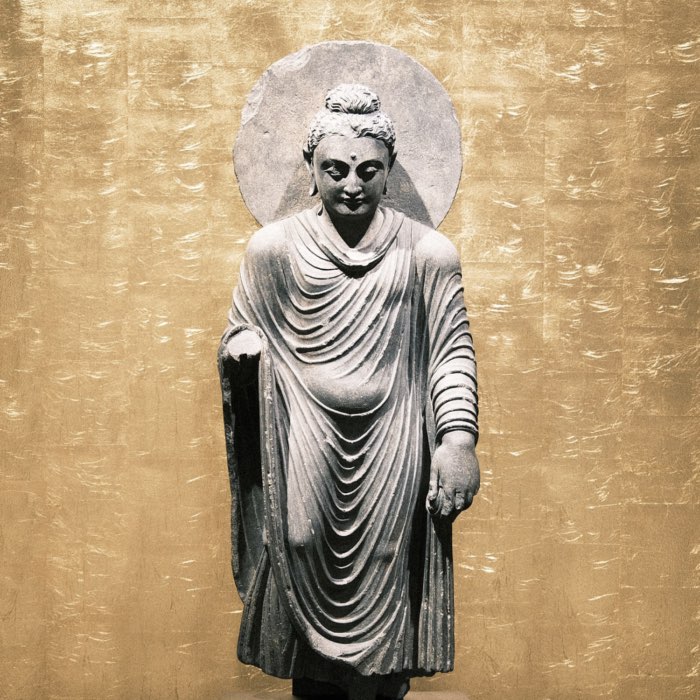

Representation of the Buddha in the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara (see also this post), 1st century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Historical and philosophical contexts

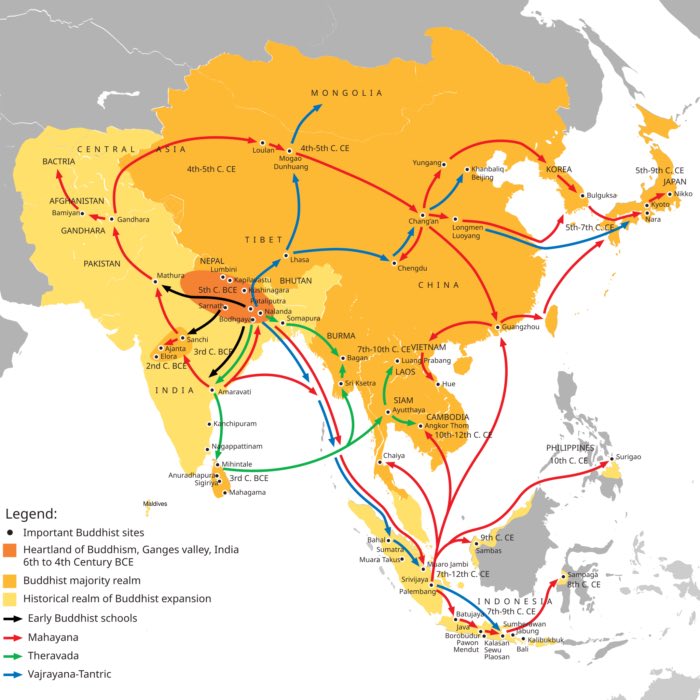

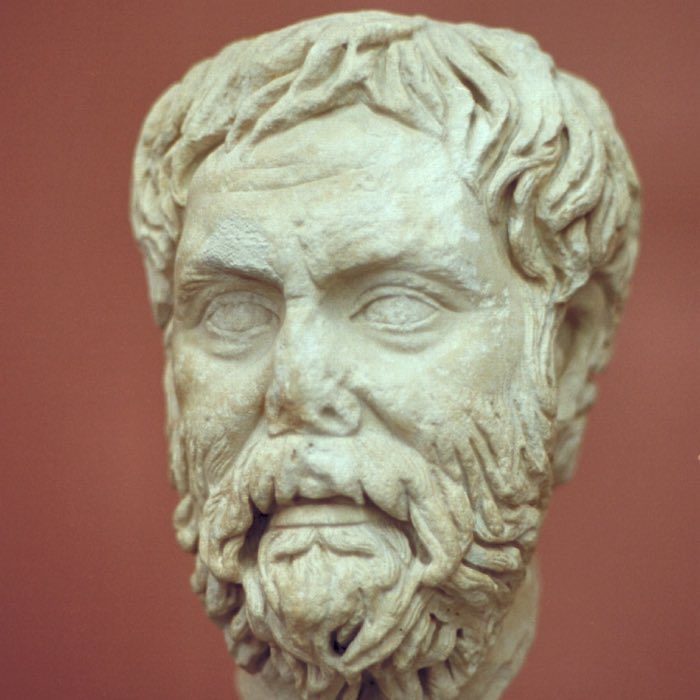

The philosophical parallels between Pyrrhonism and early Buddhism have intrigued historians and philosophers alike, leading to recurring speculation about whether Pyrrho of Elis (circa 365–275 BCE) may have encountered Indian philosophical thought directly during his travels. Pyrrho is said to have accompanied Alexander the Great’s expedition to India, where he was exposed to various religious and philosophical traditions. Diogenes Laërtius, an ancient biographer of philosophers, claims that Pyrrho was particularly impressed by the practices of the Indian gymnosophists — a term referring broadly to ascetic philosophers — and the Magi of Persia.

Map of Alexander the Great’s empire and his routes of conquest. Diogenes Laërtius’ biography of Pyrrho reports that Pyrrho traveled with Alexander the Great’s army on its conquest of India (327 to 325 BCE) and based his philosophy on what he learned there. The sources and the extent of the Indian influences on Pyrrho’s philosophy, however, are disputed. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Left: Medieval miniature reproducing the meeting of the gymnosophists with Alexander, c. 1420, Historia de proelis. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0). Right: An Indian Acharya. Acharya is a term in Indian religions for a teacher or master (guru) of a tradition. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0).

Some modern scholars argue that Pyrrho’s exposure to Indian philosophy could have influenced his development of radical skepticism, pointing to similarities between Pyrrhonism and certain strands of Buddhist thought, particularly in their shared goal of achieving mental tranquility through detachment from dogmatic beliefs. Others, however, caution against drawing direct causal connections, emphasizing that similarities could have arisen independently due to shared existential concerns across different cultures.

While the question of direct influence remains an open and fascinating topic for scholarly debate, this post sets aside historical speculation and focuses instead on a conceptual comparison between Pyrrhonism and Buddhism. By examining their core philosophical tenets, we seek to illuminate the striking convergences and critical differences in how these traditions approach the nature of belief, perception, and the human pursuit of inner peace.

Suspension of judgment and the middle path

Pyrrhonism, as documented by Sextus Empiricus, revolves around the principle of epoché — the suspension of judgment regarding the true nature of things. Pyrrhonists argue that for every claim, an equally convincing counter-claim can be presented, resulting in the inability to determine absolute truth. This deliberate withholding of assent to any proposition leads to a state of ataraxia, or tranquility, as the mind is no longer disturbed by the anxiety of conflicting beliefs.

A comparable concept appears in the Madhyamaka school of Mahayana Buddhism, founded by Nāgārjuna. The Madhyamaka philosophy is characterized by a rigorous deconstruction of all views, demonstrating that phenomena lack intrinsic existence and are thus []”empty” (śūnyatā) of inherent nature](/weekend_stories/told/2025/2025-06-15-sunyata_and_two_truths/). This philosophical approach avoids the extremes of eternalism (the belief in a permanent, unchanging essence) and nihilism (the belief in the total non-existence of things), advocating instead a “middle path” that transcends dichotomous thinking. While Pyrrhonism employs epoché to suspend judgment entirely, Madhyamaka employs dialectical reasoning to expose the limitations of conceptual thought, guiding the practitioner toward a direct experiential realization of reality’s emptiness.

Both approaches share a critical stance toward dogmatic assertions and promote mental tranquility through a form of non-attachment to fixed views. However, while Pyrrhonism treats epoché as an end in itself, Madhyamaka integrates it into a broader soteriological framework aimed at achieving nirvāṇa, or the cessation of suffering.

Non-attachment and mental tranquility

For Pyrrhonists, tranquility arises when one ceases to be disturbed by the search for ultimate truths. By adopting a stance of non-attachment toward beliefs about the world, the Pyrrhonist achieves a form of equanimity. This detachment is intellectual in nature, aimed at relieving the mind from the burden of conflicting opinions. Sextus Empiricus emphasizes that Pyrrhonists live according to appearances (phainomena) without making any claims about their ultimate reality, thereby maintaining a state of peace regardless of external circumstances.

Buddhism, particularly in its early Theravāda and later Mahayana forms, similarly advocates non-attachment, but with a broader existential scope. The Buddhist doctrine identifies craving (taṇhā) as the root cause of suffering, and the path to liberation involves not only intellectual detachment from rigid views but also emotional and volitional detachment from desires and aversions. Through ethical conduct, meditation, and insight, the practitioner gradually cultivates a state of non-attachment that culminates in nirvāṇa, a condition of unshakable peace and freedom from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (saṃsāra).

Epistemological approaches: skepticism and insight

Both Pyrrhonism and Buddhism display a profound skepticism toward the possibility of absolute knowledge. However, their approaches to skepticism differ in purpose and method. Pyrrhonism adopts a purely negative stance, emphasizing the impossibility of certain knowledge and advocating epoché as a practical response. The Pyrrhonist’s skepticism is not aimed at uncovering a deeper truth but at achieving mental tranquility by suspending belief.

Buddhism, while also skeptical of dogmatic claims, employs its skepticism as a means to an end — namely, the direct realization of the nature of reality and the attainment of liberation. In the Madhyamaka tradition, skepticism serves to dismantle conceptual fabrications, thereby opening the way to a non-conceptual understanding of emptiness. Unlike Pyrrhonism, which remains content with agnosticism, Buddhism posits that insight (prajñā) into the emptiness of phenomena leads to profound existential freedom.

Practical dimensions: living without dogma

In practice, both Pyrrhonism and Buddhism advocate living without rigid attachment to beliefs. Pyrrhonists, as Sextus Empiricus describes, adhere to customs, natural instincts, and the guidance of appearances while refraining from making ontological claims. This pragmatic approach allows them to navigate life without being troubled by the quest for certainty.

Buddhist practice, in contrast, is more structured and prescriptive. The Noble Eightfold Path offers a comprehensive guide to ethical conduct, mental discipline, and wisdom, aimed at transforming the practitioner’s entire way of being. While Pyrrhonism provides a philosophical framework for intellectual detachment, Buddhism integrates ethical and meditative practices to facilitate a holistic detachment from all forms of clinging.

Differences in ultimate goals

A crucial difference between Pyrrhonism and Buddhism lies in their ultimate goals. Pyrrhonism’s objective is ataraxia, a practical state of undisturbed tranquility achieved by suspending judgment. It remains agnostic about metaphysical or spiritual truths, focusing solely on mental peace in the face of uncertainty.

Buddhism, however, aims for nirvāṇa, the complete cessation of suffering and the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (saṃsāra). While Pyrrhonism remains content with the suspension of belief, Buddhism seeks an ultimate existential transformation through insight into the true nature of reality and the eradication of ignorance (avidyā).

Philosophical implications

The parallels between Pyrrhonism and Buddhism suggest a shared human concern with the limits of knowledge and the quest for inner peace. Both traditions challenge the assumption that certainty or absolute knowledge is necessary for a meaningful life. Instead, they propose that by letting go of rigid attachments — whether to beliefs or desires — one can achieve a profound sense of freedom and tranquility.

However, their differences highlight the diverse ways in which human cultures have addressed similar existential questions. Pyrrhonism, as a form of skeptical inquiry, offers a philosophical approach that remains within the bounds of rational discourse. Buddhism, while equally skeptical of dogmatic assertions, provides a spiritual path that combines philosophical inquiry with practical methods for personal transformation.

Conclusion

Despite their differing historical contexts and ultimate goals, Pyrrhonism and Buddhism exhibit remarkable philosophical convergences in their treatment of belief, perception, and mental tranquility. Both traditions challenge the assumption that certainty is necessary for a meaningful life, proposing instead that liberation from rigid attachments — whether to beliefs or desires — leads to profound inner peace. However, while Pyrrhonism remains within the philosophical schools of skepticism, Buddhism offers a comprehensive spiritual path aimed at existential transformation.

The question of whether Pyrrho was directly influenced by Indian philosophy remains unresolved, and any definitive claims in this regard would be speculative. Regardless of historical influence, the conceptual parallels between Pyrrhonism and Buddhism underscore the universality of certain philosophical concerns and highlight the diverse ways in which human thought has sought to address the perennial questions of existence.

References and further reading

- Hellmut Flashar, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 3. Ältere Akademie, Aristoteles, Peripatos, 2004, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 978-3-7965-1998-7

- Hellmut Flashar, Michael Erler, Günter Gawlick, Woldemar Görler, Peter Steinmetz, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd.4. Die hellenistische Philosophie, 1994, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796509308

- Malte Bossenfelder, Sextus Empiricus, Grundriss der pyrrhonischen Skepsis, 1985, Suhrkamp Verlag Frankfurt am Main

- Markus Gabriel, Skeptizismus und Idealismus in der Antike, 2009, Suhrkamp Verlag, ISBN: 3518295195

- Markus Gabriel, Skeptizismus und Metaphysik (2012), Serie: Deutsche Zeitschrift für Philosophie / Sonderbände 28, de Gruyter, ISBN: 9783050057231

- Markus Gabriel, An den Grenzen der Erkenntnistheorie: die notwendige Endlichkeit des objektiven Wissens als Lektion des Skeptizismus, 2008, Verlag Karl Alber Freiburg / München, ISBN: 9783495483183

- Richard Bett, Pyrrho, His Antecedents, and His Legacy, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780199256617

- Christopher I. Beckwith, Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia, 2015, Princeton University Press, ISBN 10: 0691166447

- Thomas C. McEvilley, The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies, 2001, Allworth, ISBN: 978-1581152036

- John Boardman, The Greeks in Asia, 2015, National Geographic Books, ISBN: 9780500252130

- Kalupahana, D. J., Buddhist Philosophy: A Historical Analysis, 1975, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-0824803926

- Garfield, J. L., The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way: Nāgārjuna’s Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, 1995, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195093360

- Gethin, R., The Foundations of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0192892232

comments