Pyrrhonism: Radical skepticism and the pursuit of tranquility

Pyrrhonism, a school of ancient skepticism founded by Pyrrho of Elis (circa 360–270 BCE), represents one of the most rigorous and distinctive philosophical traditions of the Hellenistic period. Unlike earlier Greek skeptics, who often critiqued specific dogmas or theories, Pyrrhonism advocated a radical suspension of judgment (epoché) about all matters, emphasizing the limits of human knowledge and the impossibility of attaining certain truth. This philosophical stance was not an end in itself but a means to achieving ataraxia, or tranquility of the soul, which Pyrrho and his followers regarded as the ultimate goal of human life.

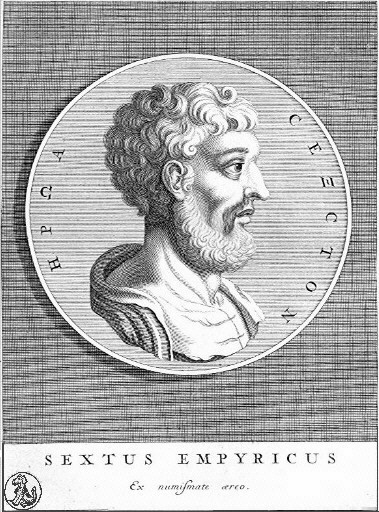

Pyrrho of Elis, marble head, early Roman copy, 2nd century BCE. Bronze Greek original was from the 4th century BCE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The origins and context of Pyrrhonism

Pyrrho of Elis, the founder of Pyrrhonism, accompanied Alexander the Great on his expeditions to the East (327 to 325 BCE), where he is believed to have encountered Indian philosophical traditions that influenced his thought.

Map of Alexander the Great’s empire and his routes of conquest. Diogenes Laërtius’ biography of Pyrrho reports that Pyrrho traveled with Alexander the Great’s army on its conquest of India (327 to 325 BCE) and based his philosophy on what he learned there. The sources and the extent of the Indian influences on Pyrrho’s philosophy, however, are disputed. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Diogenes Laërtius’ biography of Pyrrho reports:

…he even went as far as the Gymnosophists, in India, and the Magi. Owing to which circumstance, he seems to have taken a noble line in philosophy, introducing the doctrine of incomprehensibility, and of the necessity of suspending one’s judgment…

While some sources suggest that Pyrrho’s philosophy was significantly shaped by encounters with Indian traditions, the extent and nature of these influences remain a matter of scholarly debate. Philosophical skepticism was already present in Greek philosophy, particularly within the Democritus tradition, in which Pyrrho had studied prior to visiting India. On the other hand, Indian philosophical schools by this time had also developed notions of skepticism tied to composure and the suspension of judgment.

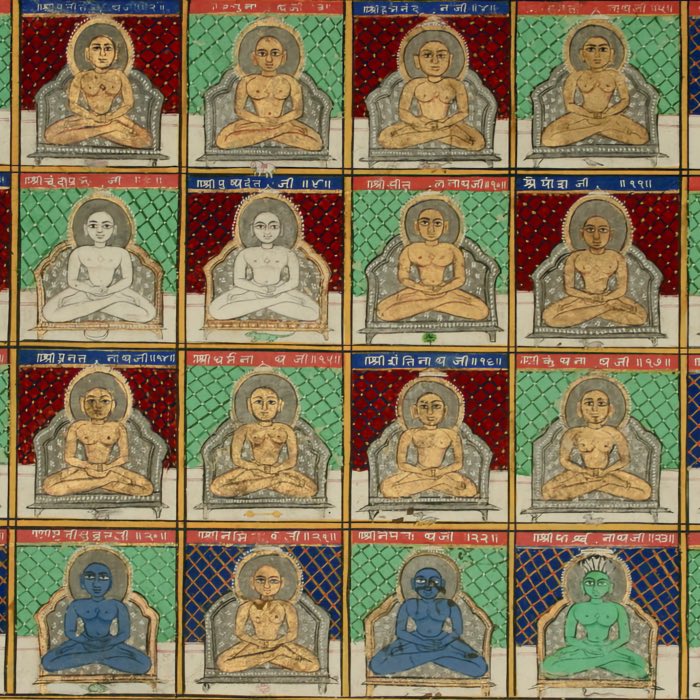

Other scholars heavily discount substantive Indian influences on Pyrrho, arguing that the testimony of Onesicritus — who noted the challenges of conversing with the gymnosophists due to the necessity of three translators, none of whom understood philosophy — makes it improbable that Pyrrho could have directly engaged with or been profoundly influenced by Indian philosophers. Nevertheless, other scholars hypothesize that the gymnosophists Pyrrho encountered may have been Jains or Ajnanins, traditions that emphasize skepticism and detachment, likely contributing to Pyrrho’s ideas.

Moreover, it has been suggested that the influence of Indian skepticism extended beyond Pyrrhonism, with potential parallels identified between Indian and Greek thought and even in Buddhism itself, which shares common ground with Pyrrhonian ideas.

Returning to Greece, Pyrrho articulated a philosophy of skepticism that challenged the epistemological and ethical assumptions of earlier thinkers, including the dogmatism of Aristotelian and Stoic systems. His ideas were systematized and expanded by later followers, most notably Aenesidemus (1st century BCE) and Sextus Empiricus (circa 2nd–3rd century CE). Sextus’ writings, particularly Outlines of Pyrrhonism and Against the Dogmatists, provide the most comprehensive account of Pyrrhonian skepticism, elucidating its principles, methods, and practical applications.

Sextus Empiricus (mid-late 2nd century CE). Sextus’ writings, particularly Outlines of Pyrrhonism and Against the Dogmatists, provide the most comprehensive account of Pyrrhonian skepticism, elucidating its principles, methods, and practical applications. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The principles of Pyrrhonian skepticism

At the heart of Pyrrhonism is the principle of epoché, the suspension of judgment about all matters, including metaphysical, ethical, and epistemological questions. Pyrrhonists argued that every assertion is counterbalanced by an equally plausible opposing assertion, rendering definitive judgment impossible. This radical stance extends to all domains of inquiry, from the nature of reality to the validity of moral norms and sensory perception.

The Pyrrhonian method involves a systematic exploration of opposing arguments, revealing the equal weight of evidence on both sides. This process, known as isostheneia (equipollence), leads to the recognition of the limits of human reason and the abandonment of dogmatic beliefs.

For Pyrrhonists, the practical goal of skepticism is ataraxia, a state of mental tranquility that arises from the absence of dogmatic commitment and the freedom from anxiety about achieving certainty. By relinquishing the quest for ultimate knowledge, individuals can attain a serene and untroubled state of mind, navigating life with openness and flexibility.

Pyrrhonism and academic skepticism

Pyrrhonism is often contrasted with Academic skepticism, the form of skepticism developed by the Platonic Academy under Arcesilaus and Carneades. While both schools shared a commitment to questioning dogmatic claims, they differed in their methods and philosophical outlooks.

Academic skeptics emphasized probabilistic reasoning, arguing that while certainty is unattainable, some beliefs are more plausible or likely than others. This stance allowed them to engage with practical and ethical issues, making judgments based on the balance of probabilities. Pyrrhonists, by contrast, rejected even probabilistic claims, maintaining that all judgments are equally uncertain and that suspension of judgment is the only rational response to the limits of human knowledge.

This distinction reflects a fundamental difference in their aims: whereas Academic skeptics sought to refine and moderate belief, Pyrrhonists aimed to transcend belief altogether, embracing a stance of radical openness and non-attachment.

The Pyrrhonian way of life

Pyrrhonism is not merely an intellectual exercise but a practical philosophy intended to guide individuals toward a fulfilling and tranquil life. The Pyrrhonian way of life involves:

- Suspension of judgment: By withholding judgment on all matters, Pyrrhonists avoid the emotional disturbances and anxieties associated with dogmatic beliefs.

- Openness to experience: Pyrrhonists engage with the world as it appears, without imposing preconceived notions or attempting to resolve unanswerable questions.

- Freedom from dogma: By avoiding both positive and negative dogmatism, Pyrrhonists maintain intellectual humility and adaptability, recognizing the provisional nature of human understanding.

Sextus Empiricus emphasized the practical benefits of this approach, noting that Pyrrhonism allows individuals to navigate life’s uncertainties with equanimity and to focus on immediate, tangible experiences rather than abstract and speculative concerns.

Pyrrhonism and Indian philosophy

The potential parallels between Pyrrhonism and Indian philosophy have long intrigued scholars. Diogenes Laërtius recorded that Pyrrho “foregathered with the Indian Gymnosophists and with the Magi”, and this exposure may have influenced his adoption of skepticism. Some researchers argue that Pyrrho’s doctrine of suspension of judgment (epoché) and its goal of achieving tranquility (ataraxia) share striking similarities with Buddhist teachings, particularly the three marks of existence: non-self (anatta), impermanence (anicca), and suffering (dukkha).

Christopher I. Beckwith contends that concepts such as adiaphora (indifference), astathmēta (instability), and anepikrita (undecidability), central to Pyrrhonian thought, align closely with these Buddhist principles. Beckwith argues that the 18 months Pyrrho spent in India were sufficient for him to learn the foundational tenets of Indian philosophy, particularly the suspension of judgment as a path to liberation—a notion central to both Pyrrhonism and Buddhism.

Nagarjuna, a Madhyamaka Buddhist philosopher whose skeptical arguments are similar to those preserved in the work of Sextus Empiricus. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Another point of convergence is the tetralemma (fourfold negation), a common feature in Buddhist logic and Pyrrhonian maxims. This logical structure explores possibilities without affirming or denying any proposition, reflecting a shared emphasis on the limits of definitive knowledge. Similarly, the Pyrrhonist notion of ataraxia resonates with the Buddhist concept of nirvana, as both describe states of peace and liberation achieved by transcending attachment to dogmatic beliefs.

Conversely, some scholars, such as Stephen Batchelor and Charles Goodman, caution against overstating these parallels, noting differences in metaphysical assumptions. For example, Pyrrhonism lacks the doctrines of karma and rebirth, which are central to Buddhism. Furthermore, while ataraxia is a psychological state focused on moderation and tranquility in this life, nirvana represents a profound metaphysical liberation from the cycle of rebirth.

Ajñana, a school of Indian skepticism emphasizing radical doubt and detachment, may have also influenced Pyrrho. Known as the “eel-wrigglers” for their refusal to commit to any doctrine, Ajñana’s skepticism aligns with Pyrrho’s emphasis on withholding judgment and embracing indeterminacy.

Despite ongoing debates, the cross-cultural dialogue between Greek and Indian philosophy highlights the universality of philosophical inquiry. Whether through direct influence or independent convergence, the shared themes of skepticism, detachment, and the pursuit of tranquility underscore a profound intellectual kinship.

Conclusion

Pyrrhonism represents one of the most radical and enduring expressions of skepticism in the history of Western philosophy. By challenging the possibility of certain knowledge and advocating the suspension of judgment (epoché), Pyrrhonists critiqued dogmatism and offered a method for achieving tranquility (ataraxia). Their intellectual humility and emphasis on the limits of human understanding fostered a tradition of critical inquiry that shaped ancient thought, influencing schools such as Stoicism and Aristotelianism.

During the Renaissance and Enlightenment, the rediscovery of Sextus Empiricus’ writings inspired figures like Montaigne, Descartes, and Hume, contributing to the development of modern scientific methodology. Pyrrhonian skepticism emphasized the provisional nature of knowledge, the importance of empirical observation, and the need for critical reasoning—principles that remain foundational to contemporary scientific and philosophical inquiry.

In contemporary philosophy, Pyrrhonism continues to resonate in debates about epistemology, relativism, and the limits of certainty. Its potential parallels to Indian philosophical traditions highlight its universal relevance, reflecting shared concerns about belief, knowledge, and inner peace across cultures. By questioning the foundations of human understanding, Pyrrhonism remains a vital framework for exploring the complexities of truth, belief, and tranquility.

Scales in balance: modern symbol of Pyrrhonism. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

References and further reading

- Hellmut Flashar, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 3. Ältere Akademie, Aristoteles, Peripatos, 2004, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 978-3-7965-1998-7

- Hellmut Flashar, Michael Erler, Günter Gawlick, Woldemar Görler, Peter Steinmetz, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd.4. Die hellenistische Philosophie, 1994, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796509308

- Malte Bossenfelder, Sextus Empiricus, Grundriss der pyrrhonischen Skepsis, 1985, Suhrkamp Verlag Frankfurt am Main

- Markus Gabriel, Skeptizismus und Idealismus in der Antike, 2009, Suhrkamp Verlag, ISBN: 3518295195

- Markus Gabriel, Skeptizismus und Metaphysik (2012), Serie: Deutsche Zeitschrift für Philosophie / Sonderbände 28, de Gruyter, ISBN: 9783050057231

- Markus Gabriel, An den Grenzen der Erkenntnistheorie: die notwendige Endlichkeit des objektiven Wissens als Lektion des Skeptizismus, 2008, Verlag Karl Alber Freiburg / München, ISBN: 9783495483183

- Richard Bett, Pyrrho, His Antecedents, and His Legacy, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780199256617

- Christopher I. Beckwith, Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia, 2015, Princeton University Press, ISBN 10: 0691166447

- Thomas C. McEvilley, The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies, 2001, Allworth, ISBN: 978-1581152036

- John Boardman, The Greeks in Asia, 2015, National Geographic Books, ISBN: 9780500252130

comments