Plato: The philosopher of forms and the architect of Western thought

Plato (circa 427–347 BCE) is one of the most influential figures in the history of Western philosophy. A student of Socrates and the teacher of Aristotle, he founded the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world, and developed a comprehensive philosophical system that has shaped intellectual discourse for over two millennia. His dialogues, written in a dramatic and literary style, address fundamental questions about reality, knowledge, ethics, politics, and art, weaving together metaphysical speculation, ethical inquiry, and practical concerns.

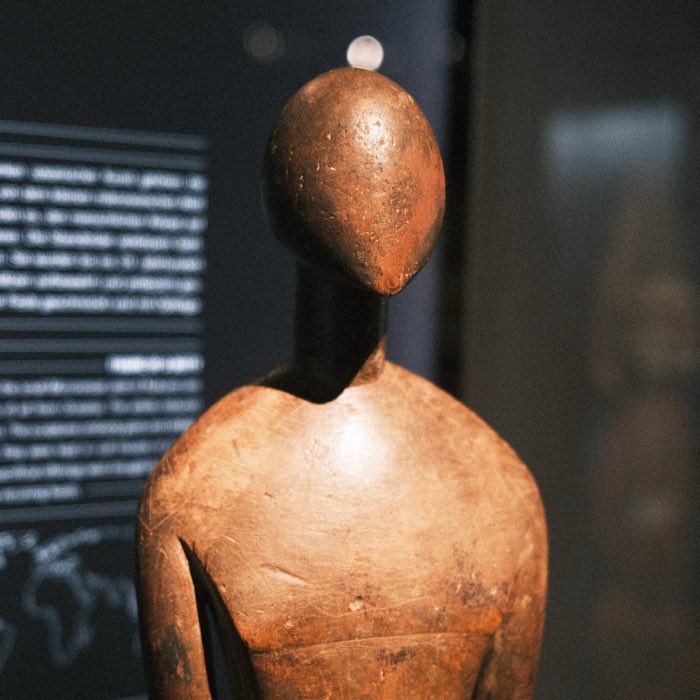

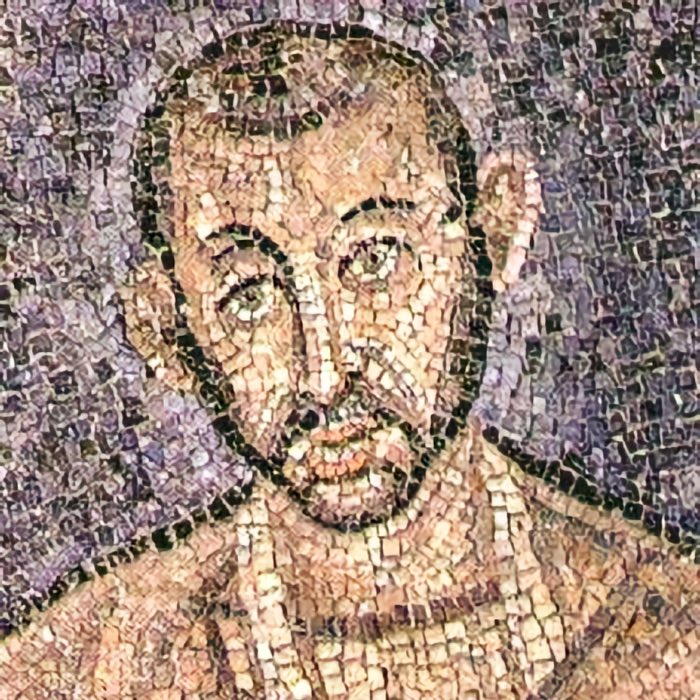

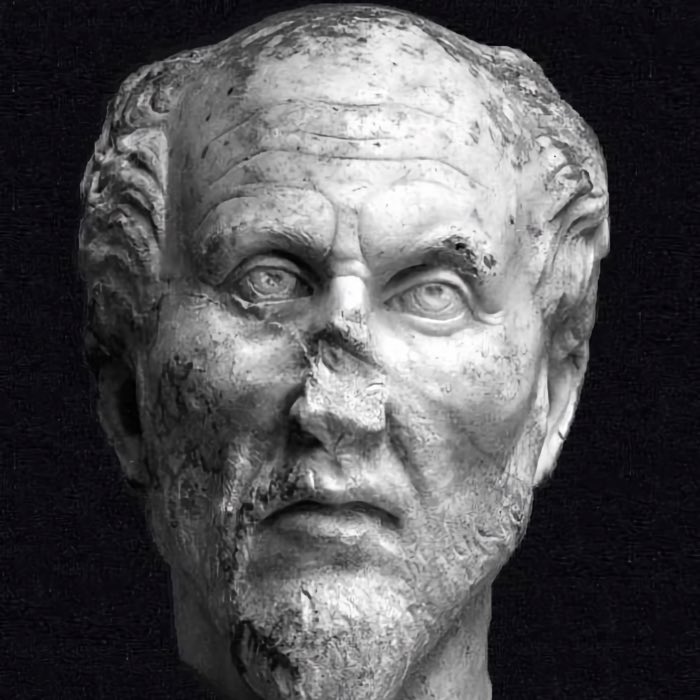

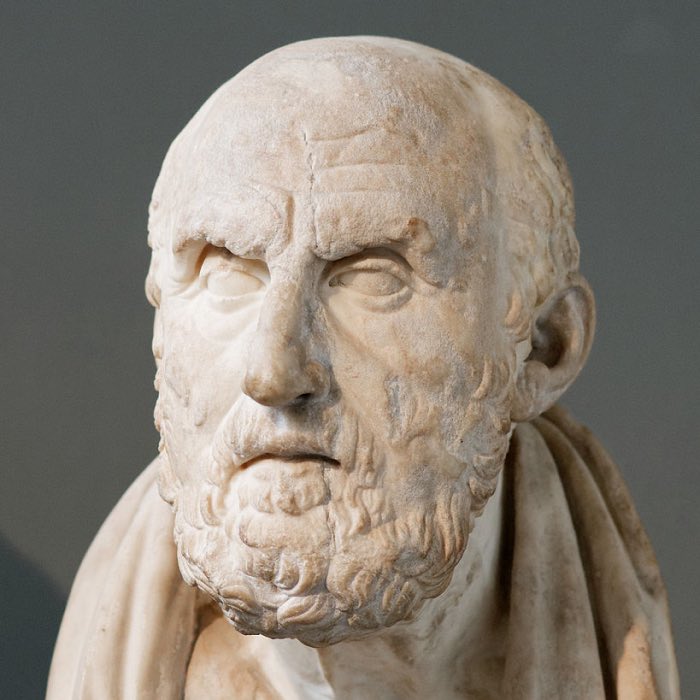

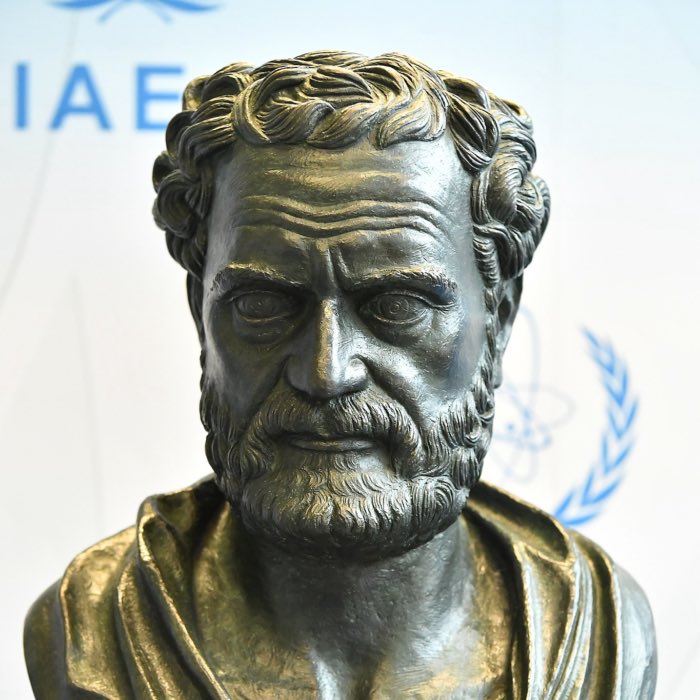

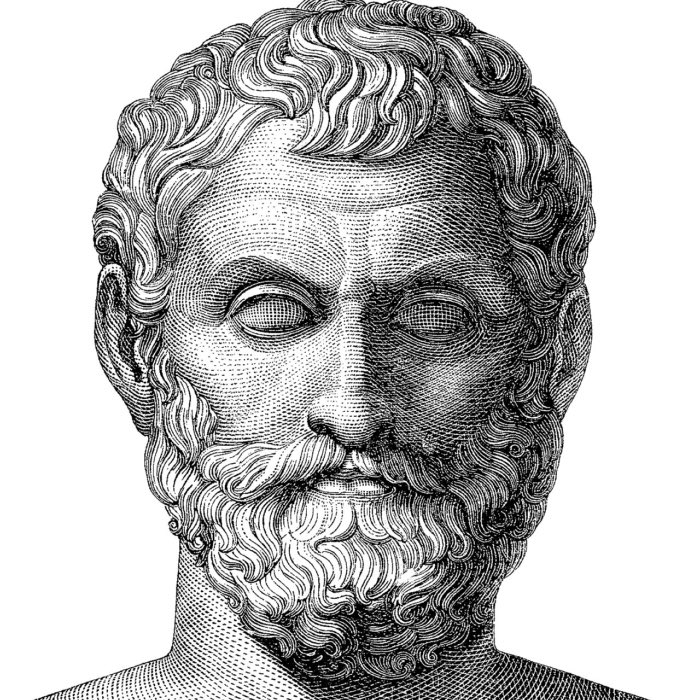

Roman copy of a Greek portrait of Plato, probably by Silanion, which was placed in the Academy after Plato’s death, Glyptothek Munich. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The life and context of plato

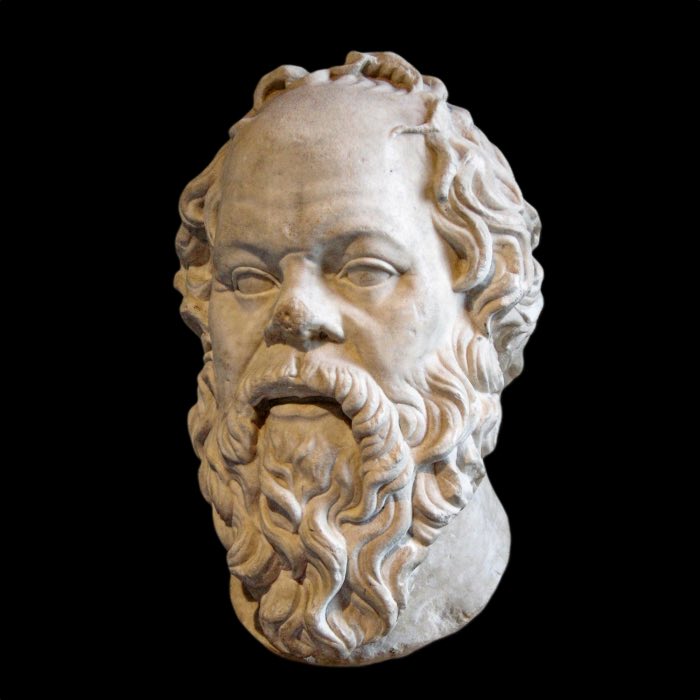

Plato was born into an aristocratic family in Athens during a period of political upheaval and cultural flourishing. He was profoundly influenced by Socrates, whose method of questioning and emphasis on ethical inquiry became central to his own philosophy. The execution of Socrates in 399 BCE marked a turning point in Plato’s life, prompting him to critique the shortcomings of Athenian democracy and to envision a more just and rational political order.

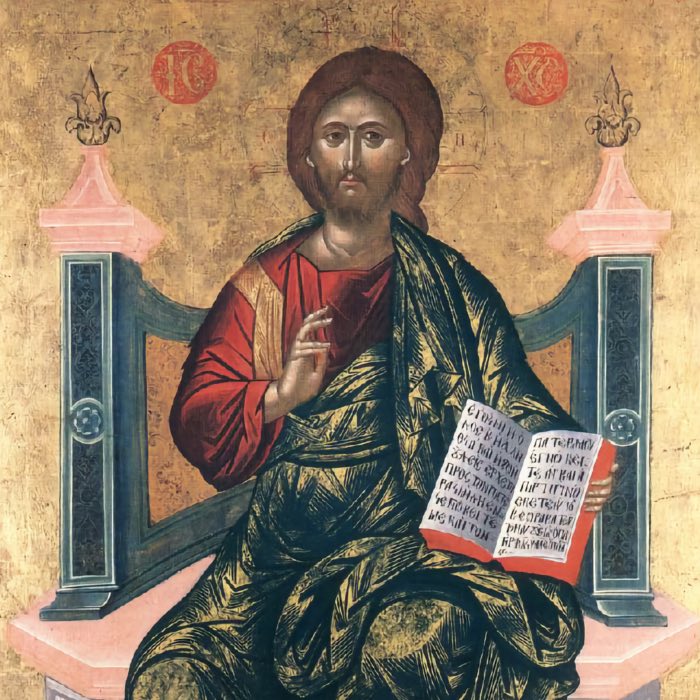

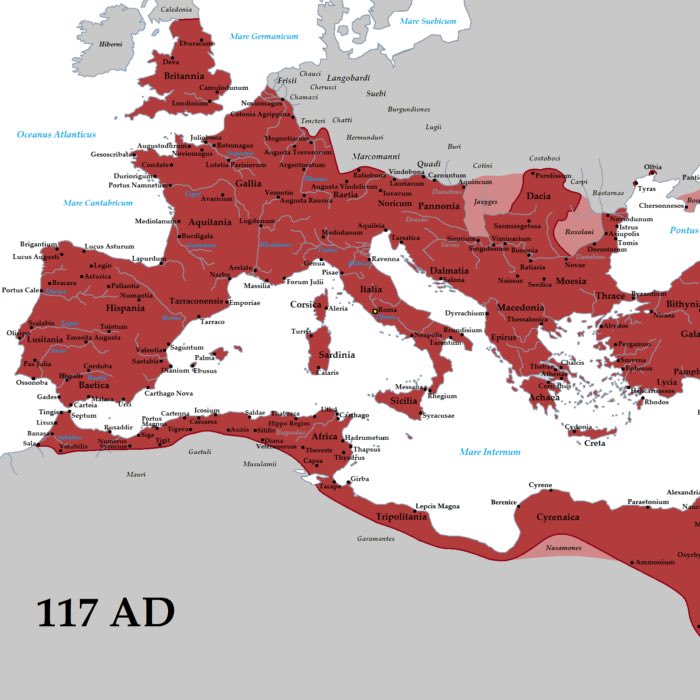

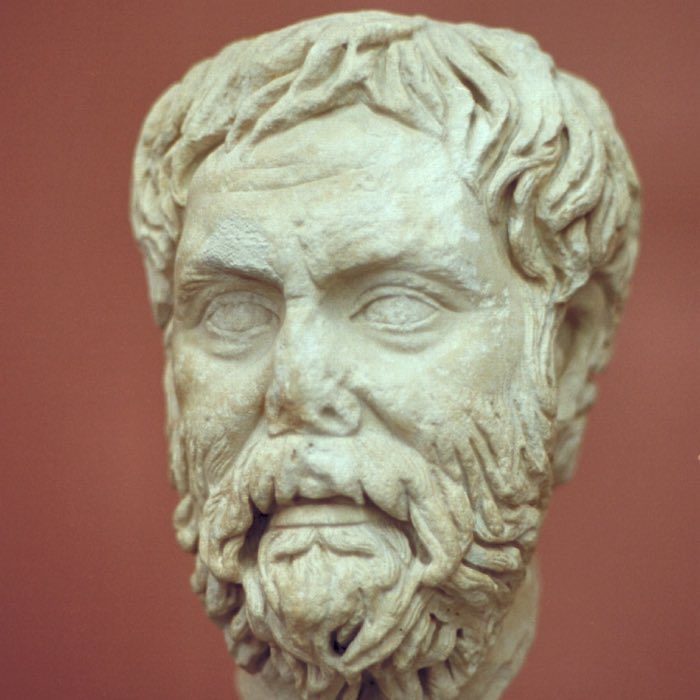

Plato’s Academy, mosaic floor in Pompeii, 1st century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Plato traveled extensively, studying in Italy and Egypt, and founded the Academy upon his return to Athens. The Academy served as a center for philosophical, scientific, and mathematical research, attracting students and scholars from across the Greek world. Plato’s dialogues, written throughout his life, reflect his engagement with the intellectual and political challenges of his time, offering a vision of philosophy as a means of achieving personal and collective excellence.

The Theory of forms: Plato’s metaphysical framework

At the heart of Plato’s philosophy is the theory of forms, a metaphysical system that distinguishes between the world of appearances, accessible through the senses, and the world of forms, accessible through reason. Forms are perfect, immutable, and eternal entities that represent the true reality underlying the imperfect and transient objects of the material world. For example, individual instances of beauty, justice, or goodness in the material world are mere reflections or approximations of the ideal forms of Beauty, Justice, and the Good.

Plato’s theory of forms addresses fundamental philosophical questions about the nature of reality, the basis of knowledge, and the possibility of objective truth. By positing the existence of a transcendent realm of forms, Plato provides a foundation for understanding the unity and consistency of concepts despite the diversity and variability of their manifestations in the material world.

This metaphysical framework is most famously articulated in the Republic, where Plato uses the allegory of the cave to illustrate the contrast between the world of appearances and the world of forms. In the allegory, prisoners in a cave mistake shadows on a wall for reality, unaware of the true forms that cast those shadows. The philosopher, through education and reason, escapes the cave and ascends to the realm of the forms, attaining knowledge of the ultimate realities that govern existence.

Epistemology: Knowledge and the ascent to the forms

Plato’s epistemology is closely tied to his metaphysics, emphasizing the distinction between knowledge (episteme) and opinion (doxa). For Plato, knowledge is not derived from sensory experience, which is subject to error and change, but from intellectual apprehension of the forms. This rationalist approach asserts that true knowledge involves understanding the eternal and unchanging principles that underlie the material world.

Plato describes the process of attaining knowledge as an ascent, moving from the perception of particular objects to the contemplation of universal truths. In the Symposium and Phaedrus, this ascent is depicted as an erotic and spiritual journey, where the soul is drawn toward the beauty and perfection of the forms. In the Republic, the ascent is described as a process of dialectical reasoning, where the philosopher progresses from hypotheses to first principles, culminating in the vision of the form of the Good, the ultimate source of truth and reality.

Ethics and the good life

Plato’s ethical philosophy centers on the concept of the Good, which he identifies as the highest form and the ultimate goal of human life. The Good is the source of all value, order, and harmony in the universe, providing the standard by which all actions and choices are judged. For Plato, a virtuous life is one that aligns with the Good, achieved through the cultivation of wisdom, courage, moderation, and justice.

In the Republic, Plato explores the relationship between individual virtue and social justice, arguing that a just society is one in which each individual fulfills their proper role in accordance with their nature and abilities. He divides the soul into three parts — reason, spirit, and appetite — corresponding to the classes of the ideal state: rulers, guardians, and producers. Justice, both in the individual and in the state, arises when each part performs its function in harmony with the whole.

Plato’s ethics also emphasize the importance of education and philosophical inquiry in achieving the Good. He believed that ignorance is the root of moral failure and that true virtue requires knowledge of the forms, particularly the form of the Good.

Political philosophy: The ideal state

Plato’s political philosophy, as presented in the Republic and later in the Laws, is an extension of his ethical and metaphysical theories. He envisions the ideal state as a reflection of the order and harmony of the forms, governed by philosopher-kings who possess the wisdom and virtue necessary to rule justly. In the Republic, Plato argues that the philosopher-king, having ascended to the realm of the forms and attained knowledge of the Good, is uniquely qualified to guide society toward justice and the common good.

Plato’s political philosophy critiques the shortcomings of existing political systems, particularly Athenian democracy, which he saw as prone to corruption and instability. His ideal state is hierarchical, with a strict division of labor based on the natural aptitudes of individuals. While this vision has been criticized as authoritarian, it reflects Plato’s commitment to rational governance and his belief in the transformative power of philosophy.

In the Laws, Plato offers a more pragmatic and less utopian vision of political order, emphasizing the importance of laws and institutions in promoting virtue and stability. This later work demonstrates his recognition of the complexities and limitations of human society.

Aesthetics: Art and the soul

Plato’s aesthetics, as explored in the Republic and other dialogues, reflect his ambivalence toward art and its role in human life. While he acknowledges the power of art to inspire and educate, he also criticizes its capacity to mislead and corrupt. Plato argues that art, as a mere imitation of the material world, is twice removed from the truth of the forms. He is particularly concerned with the moral and psychological effects of poetry and drama, which he believes can inflame the passions and undermine reason.

Despite these critiques, Plato’s philosophy contains a deep appreciation for the transformative potential of beauty, which he identifies as a bridge between the material and the divine. In the Symposium, he describes the experience of beauty as a stepping stone toward the contemplation of the Good, highlighting the aesthetic dimension of his metaphysical and ethical thought.

Conclusion

Plato’s philosophy represents a monumental achievement in the history of Western thought, shaping fields as diverse as metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, political theory, and aesthetics. His dialogues have profoundly influenced the development of Western thought, providing the foundation for Neoplatonism and shaping early Christian theology through the works of Augustine and other Church Fathers.

In the modern era, Plato’s ideas continue to inspire debates about the nature of reality, the limits of human knowledge, and the principles of justice and governance. His theory of forms, dialectical method, and vision of philosophy as a transformative pursuit of truth and virtue offer a model of intellectual inquiry that integrates reason, imagination, and ethical commitment. Plato established the foundations of Western philosophy and provided a framework for understanding the complexities of the human condition.

References and further reading

- Michael Erler, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 2/2. Platon, 2007, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 978-3-7965-2237-6

- Hellmut Flashar, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 3. Ältere Akademie, Aristoteles, Peripatos, 2004, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 978-3-7965-1998-7

- David Ebrey, The Cambridge Companion to Plato, 2022, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1108457262

- Annas, J., An Introduction to Plato’s Republic, 1989, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0198274292

- Fine, G., On Ideas: Aristotle’s Criticism of Plato’s Theory of Forms, 1995, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0198235491

- Guthrie, W. K. C., A History of Greek Philosophy, Volume IV: Plato: The Man and His Dialogues, 1975, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521200028

- Ferrari, G. R. F., City and Soul in Plato’s Republic, 2005, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226244372

comments