The Epicureans: Philosophy of pleasure, tranquility, and the pursuit of happiness

The Epicurean school, founded by Epicurus (341–270 BCE), represents one of the most distinctive and enduring philosophical movements of the Hellenistic period. At its heart lies a hedonistic philosophy that defines the highest good as the attainment of pleasure (hedone), understood not as indulgence in sensual excess but as the cultivation of a tranquil and virtuous life. Epicureanism offered a comprehensive framework addressing metaphysics, ethics, and epistemology, emphasizing the naturalistic basis of existence and the role of rational inquiry in achieving human flourishing (eudaimonia).

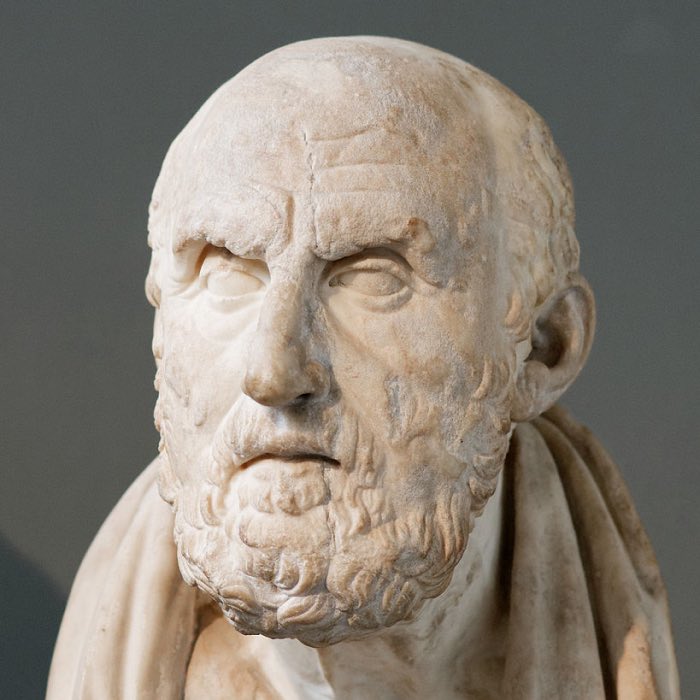

Epicurus, founder of the Epicurean school. Roman copy after a lost Hellenistic original. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The life and context of Epicurus

Epicurus was born on the island of Samos in 341 BCE and began his philosophical education under the influence of Democritus’ atomism and the ethical teachings of Socratic and Cynic traditions. Dissatisfied with the metaphysical speculations of Plato and Aristotle, as well as the moral austerity of the Cynics, Epicurus sought to create a practical philosophy grounded in the realities of human life and nature.

Around 306 BCE, Epicurus founded his school in Athens, establishing “The Garden” as a philosophical retreat open to individuals of all genders and social classes. The Garden emphasized equality, intellectual discourse, and the pursuit of a serene and self-sufficient life. Epicurus’ teachings, preserved through fragments, letters, and later summaries by authors such as Lucretius, reflect his commitment to creating a philosophy that directly addresses the needs and aspirations of human beings.

The metaphysics of atomism: A naturalistic foundation

Epicurus adopted and adapted the atomistic physics of Democritus, positing that the universe consists of atoms and the void. Atoms are indivisible, eternal particles in constant motion, while the void provides the empty space necessary for their movement. Through their random collisions and combinations, atoms give rise to the diversity of phenomena observed in the natural world.

Epicurus introduced the concept of the clinamen or “swerve”, a spontaneous deviation in the motion of atoms. This innovation served to explain the emergence of novelty and free will in an otherwise deterministic system, allowing for the possibility of human agency and moral responsibility.

By grounding his metaphysics in atomism, Epicurus rejected the teleological explanations of Plato and Aristotle, as well as the interventionist gods of traditional Greek religion. Instead, he presented a universe governed by natural laws and devoid of divine purpose, emphasizing that understanding these laws is essential for dispelling fear and achieving tranquility.

Overcoming fear: Death and the gods

Epicurean philosophy addresses two central sources of human anxiety: the fear of death and the fear of the gods. Epicurus sought to eliminate these fears by demonstrating their irrationality through rational analysis.

The fear of death

Epicurus argued that death is not to be feared, as it represents the cessation of sensation and consciousness. In his famous Letter to Menoeceus, he wrote:

“Death is nothing to us, for what has been dissolved has no sensation, and what has no sensation is nothing to us.”

By recognizing that death is neither painful nor harmful to the individual, Epicurus sought to liberate people from the existential dread that often undermines their capacity for happiness.

The fear of the gods

Epicurus rejected the notion of gods as active agents in human affairs, asserting instead that they exist as distant and indifferent beings, uninvolved in the workings of the universe. He argued that traditional beliefs in divine punishment and supernatural intervention were based on ignorance and superstition. This nowhere is better expressed than in the so-called Epicurean paradox:

Is God willing to stop evil, but unable?

Then he is not powerful.

Is he able, but unwilling?

Then he is not good.

Is he both able and willing?

Then how can there be evil? s he neither able nor willing?

Then why call him God?

Epicurus’ paradox examines the logical consistency of three divine attributes: omnipotence (all-powerful), omniscience (all-knowing), and omnibenevolence (all-good). It suggests that if any two of these attributes are true, the third cannot be, creating a trilemma. This paradox implies that if it is illogical for one attribute to coexist with the others, then a god possessing all three attributes cannot exist. The potential contradictions between these pairs are as follows:

- If a god knows everything and has unlimited power, then it has knowledge of all evil and has the power to put an end to it. But if it does not end it, it is not completely benevolent.

- If a god has unlimited power and is completely good, then it has the power to extinguish evil and want to extinguish it. But if it does not do it, its knowledge of evil is limited, so it is not all-knowing.

- If a god is all-knowing and totally good, then it knows of all the evil that exists and wants to change it. But if it does not, it must be because it is not capable of changing it, so it is not omnipotent.

By adopting a naturalistic view of the cosmos, Epicurus encouraged individuals to focus on their own lives and well-being rather than appeasing capricious deities.

Marble relief from the first or second century showing the mythical transgressor Ixion being tortured on a spinning fiery wheel in Tartarus. Epicurus taught that stories of such punishment in the afterlife are ridiculous superstitions and that believing in them prevents people from attaining ataraxia. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Tetrapharmakos

The Tetrapharmakos presents a summary of the key points of Epicurean ethics:

- Don’t fear god

- Don’t worry about death

- What is good is easy to get

- What is terrible is easy to endure

Ethics: Pleasure, virtue, and the good life

The central ethical doctrine of Epicureanism is that pleasure is the highest good and the ultimate goal of human life. However, Epicurus distinguished between different kinds of pleasure, emphasizing the importance of katastematic (static) pleasures, which involve the absence of pain and disturbance, over kinetic (active) pleasures, which involve fleeting sensations of joy or excitement.

Epicurus advocated for a life of moderation and simplicity, arguing that the greatest pleasures arise from the satisfaction of natural and necessary desires, such as food, shelter, and friendship. By avoiding unnecessary desires, such as the pursuit of wealth, fame, or luxury, individuals can achieve a state of inner tranquility (ataraxia) and freedom from anxiety.

Virtue, in the Epicurean framework, is not an end in itself but a means to achieving pleasure and tranquility. By cultivating virtues such as prudence, justice, and temperance, individuals can navigate life’s challenges more effectively and maintain harmonious relationships with others.

Epistemology: Knowledge and the canon

Epicurus developed a theory of knowledge based on empirical observation and the reliability of sensory perception. He argued that all knowledge originates in the senses, which provide a direct and truthful connection to the external world. While sensory perceptions are always accurate, errors arise in the interpretation of these perceptions, underscoring the importance of rational inquiry and critical thinking.

The Epicureans identified three criteria of truth, collectively known as the Canon:

- sensations (aisthēsis),

- preconceptions (prolepsis), and

- feelings (pathē).

Sensations provide immediate information about the world, preconceptions represent general concepts formed through experience, and feelings guide ethical decision-making by signaling pleasure or pain. Together, these criteria form the basis for understanding and navigating reality.

Community and friendship

Epicurus placed great importance on friendship as a cornerstone of the good life. In The Principal Doctrines, he declared that “Of all the things that wisdom provides for the happiness of the whole life, by far the greatest is the possession of friendship.” The Garden served as a model for this ideal, fostering a community of mutual support, shared values, and intellectual companionship.

Epicurus viewed friendship as both a source of pleasure and a practical necessity, offering protection, comfort, and the opportunity for philosophical discussion. Unlike familial or political relationships, which are often shaped by obligation and hierarchy, Epicurean friendship is freely chosen and grounded in mutual respect and affection.

The legacy of Epicureanism

Epicureanism had a profound impact on ancient thought, influencing figures such as the Roman poet Lucretius, whose epic poem De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things) eloquently articulated Epicurean philosophy. Despite facing criticism from rival schools such as the Stoics and early Christians, Epicurean ideas persisted, contributing to the development of natural philosophy, ethics, and materialist metaphysics.

Roman fresco from Pompeii from the 1st century CE showing the mythical human sacrifice of Iphigenia, daughter of Agamemnon. The Roman poet Lucretius, a follower of Epicurus, cited this myth as an example of the evils of popular religion, in contrast to the wholesome theology advocated by Epicurus. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

In the modern era, Epicureanism has been reinterpreted and revived in various forms, inspiring discussions of secular humanism, well-being, and the role of pleasure in a meaningful life. Its emphasis on reason, simplicity, and the rejection of fear and superstition continues to resonate with individuals seeking a philosophy of life grounded in human nature and the pursuit of happiness.

Conclusion

The Epicurean school offers a profound and practical vision of the good life (eudaimonia), grounded in the pursuit of pleasure (hedone), the cultivation of tranquility (ataraxia), and the understanding of nature (physis). By addressing the fundamental anxieties of human existence and providing a rational framework for ethical living, Epicurus and his followers created a philosophy that remains relevant and inspiring. Their legacy reflects the human quest for happiness, wisdom, and freedom.

References and further reading

- Hellmut Flashar, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 3. Ältere Akademie, Aristoteles, Peripatos, 2004, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 978-3-7965-1998-7

- Hellmut Flashar, Michael Erler, Günter Gawlick, Woldemar Görler, Peter Steinmetz, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd.4. Die hellenistische Philosophie, 1994, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796509308

- Long, A. A., Hellenistic Philosophy: Stoics, Epicureans, Sceptics, 1981, Bristol Classical Press, ISBN: 978-0715612385

- Long, A. A., & Sedley, D., The Hellenistic Philosophers, Volume 1: Translations of the Principal Sources with Philosophical Commentary, 1987, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521275569

- Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, 2009, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199555147

- Annas, J., The Morality of Happiness, 1995, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195096521

- O’Keefe, T., Epicureanism, 2009, Routledge, ISBN: 978-1844651702

- Keimpe Algra, Jonathan Barnes, Jaap Mansfeld, The Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy, 2005, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521616706

- Wikipedia article on Epicurus’ paradoxꜛ

comments