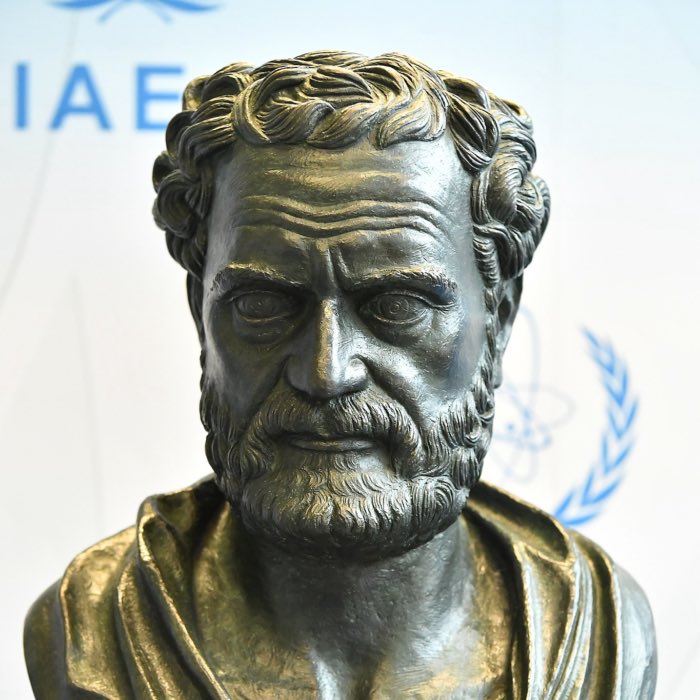

Aristotle: The philosopher of systematic thought and foundational inquiry

Aristotle (384–322 BCE) stands as one of the towering figures in Western philosophy, whose influence has extended far beyond the boundaries of his time. A student of Plato and tutor to Alexander the Great, Aristotle was a polymath who made foundational contributions to nearly every field of knowledge available in his era. From metaphysics and ethics to biology and political theory, his systematic approach to inquiry and his commitment to empirical observation set him apart as a pivotal thinker in the history of philosophy.

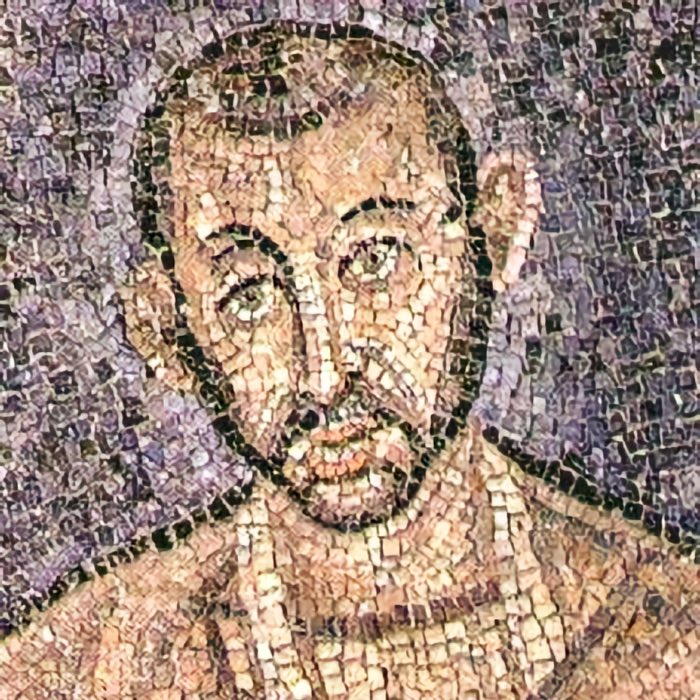

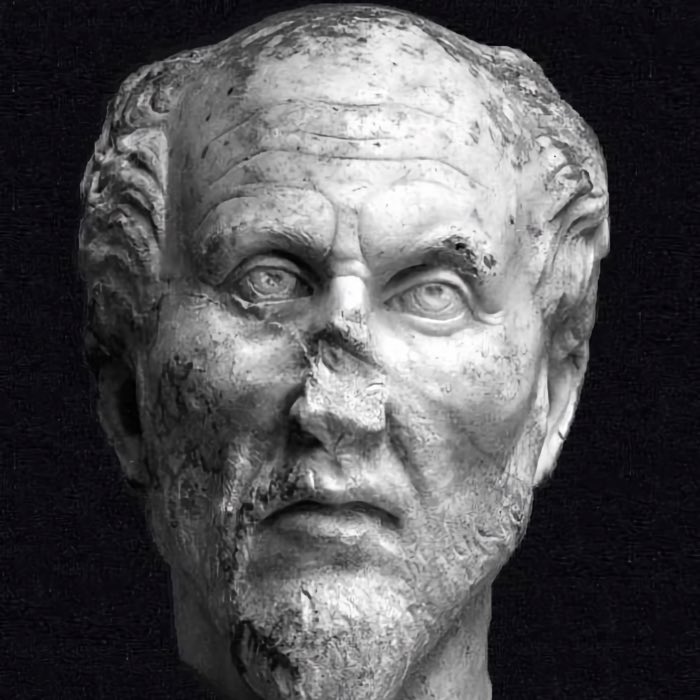

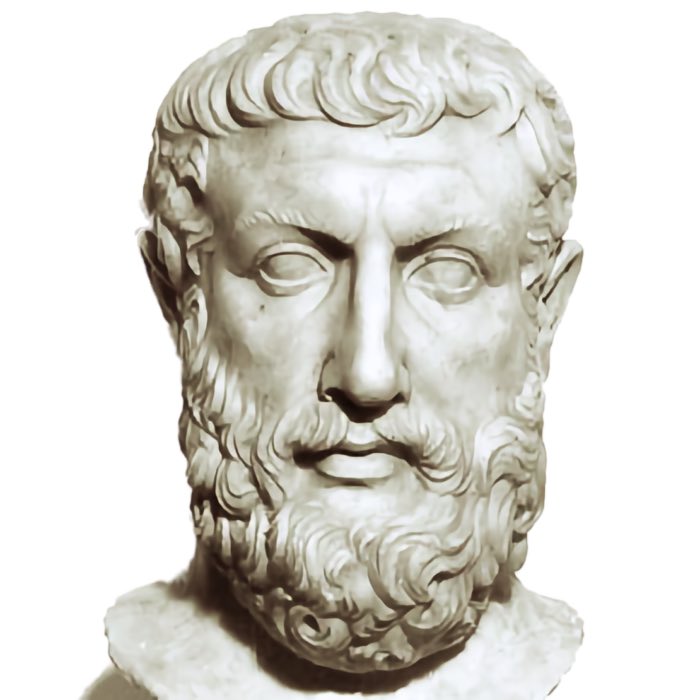

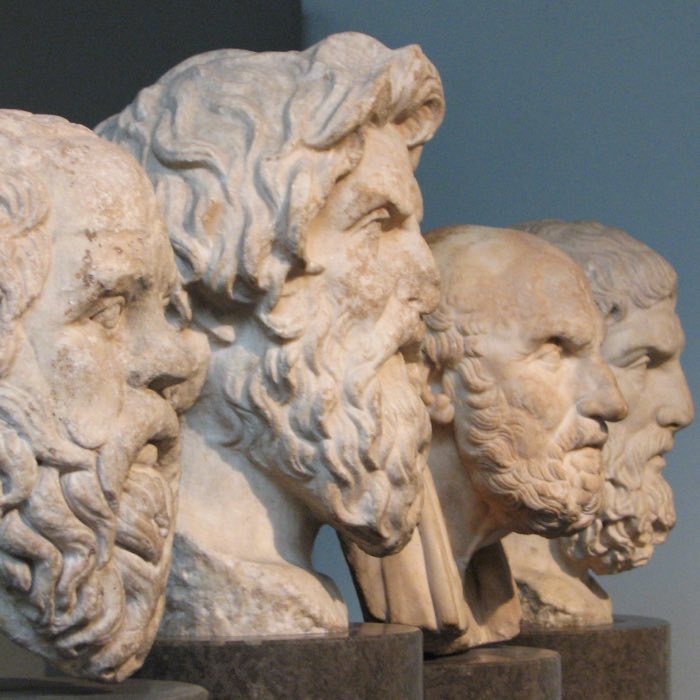

Portrait bust of Aristotle; an Imperial Roman (1st or 2nd century AD) copy of a lost bronze sculpture made by Lysippos. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

The life of Aristotle: A contextual overview

Aristotle was born in Stagira, a small town in northern Greece, to Nicomachus, a physician in the court of King Amyntas of Macedon. This early exposure to medical practices likely influenced Aristotle’s empirical approach to knowledge. At the age of 17, he moved to Athens to study at Plato’s Academy, where he remained for 20 years. Although deeply influenced by Plato’s philosophy, Aristotle diverged significantly from his teacher, particularly in his rejection of Plato’s theory of Forms, favoring a more grounded approach to understanding reality.

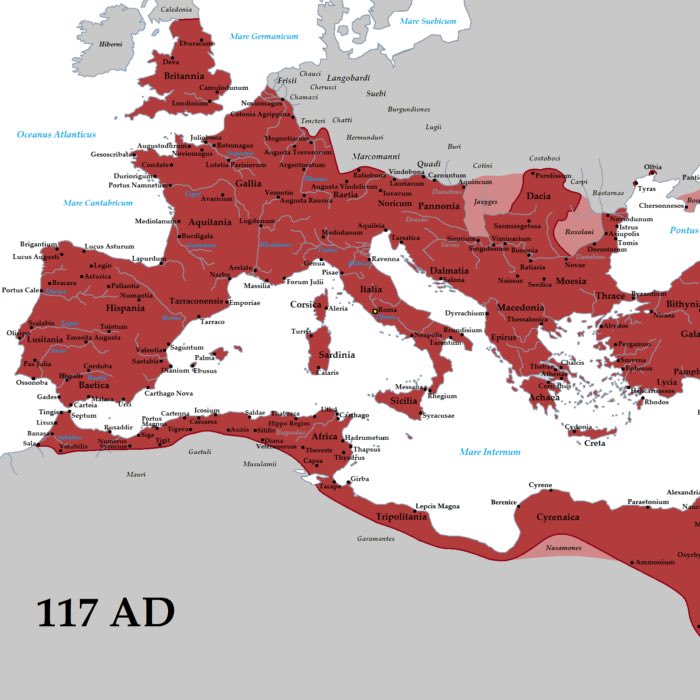

After Plato’s death, Aristotle left Athens and spent years traveling, engaging in research, and tutoring, most notably serving as the teacher of Alexander the Great. Returning to Athens around 335 BCE, Aristotle founded his own school, the Lyceum, where he conducted extensive research and developed many of his major works. Following political turmoil and charges of impiety, he fled Athens, reportedly declaring that he would not allow the Athenians to “sin twice against philosophy”, referencing Socrates’ earlier fate. Aristotle died in 322 BCE in Chalcis.

Aristotle’s method: Systematic inquiry and empiricism

One of Aristotle’s greatest contributions to philosophy is his systematic approach to inquiry. In contrast to Plato’s emphasis on ideal Forms and abstract reasoning, Aristotle grounded his philosophy in empirical observation and the classification of the natural world. His method combined logical rigor with careful observation, creating a framework for disciplines as diverse as natural science, ethics, and politics.

The Organon: Logic as a tool for knowledge

Aristotle is often credited with founding formal logic. His works collectively known as the Organon (Greek for “instrument”) lay the groundwork for deductive reasoning, particularly the syllogism. In a syllogism, two premises lead to a logical conclusion (e.g., “All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal”). Aristotle viewed logic as the foundation for all scientific inquiry, a tool to ensure consistency and validity in reasoning.

Empirical observation and classification

Aristotle’s approach was deeply empirical, grounded in observation and categorization. In his biological studies, for instance, he dissected animals and classified them based on their anatomy and behavior, creating one of the earliest systematic frameworks for zoology. Although some of his conclusions have since been revised, his emphasis on observation laid the groundwork for the scientific method.

The four causes

Central to Aristotle’s philosophy is the concept of causality, which he divided into four types:

- Material cause: What something is made of.

- Formal cause: The structure or essence of a thing.

- Efficient cause: The agent or process that brings something into being.

- Final cause: The purpose or goal for which something exists.

This framework allowed Aristotle to analyze objects and phenomena holistically, considering not only their composition and origin but also their function and purpose.

Major contributions to philosophy and science

Aristotle’s contributions are vast, touching on virtually every area of intellectual inquiry. His works have shaped not only the trajectory of Western thought but also the development of fields such as ethics, metaphysics, biology, and political theory.

Metaphysics: The study of being and substance

In his work Metaphysics, Aristotle explores the nature of being (ontology) and the underlying principles of existence. He introduces the concept of substance (ousia) as the fundamental reality underlying change and multiplicity. For Aristotle, understanding substance involves identifying its essence, which is tied to its form and purpose.

He also posits the existence of a Prime Mover — an unchanging, immaterial cause of all motion and change in the universe. This concept would later influence medieval theological discussions about God.

Ethics: The pursuit of the good life

In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle investigates the question of how humans can achieve eudaimonia — often translated as “happiness” or “flourishing.” He argues that the good life is one of rational activity in accordance with virtue, achieved through a balance between extremes (the “Golden Mean”). For example, courage is the mean between recklessness and cowardice.

Aristotle’s ethical framework is grounded in the idea that humans are rational and social beings, and that virtue is cultivated through habituation and deliberate practice. His ethics remain influential in contemporary virtue ethics, which emphasizes character and practical wisdom over rigid moral rules.

Politics: The nature of community and governance

In Politics, Aristotle examines the organization of human communities, arguing that the state exists to promote the good life for its citizens. He classifies different forms of government — monarchy, aristocracy, and polity — and their corrupt counterparts — tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy. Aristotle advocates for a mixed government that balances the interests of different social classes, emphasizing the importance of education and civic virtue.

Natural science and biology

Aristotle’s biological works, such as History of Animals and Parts of Animals, reflect his keen interest in the natural world. He documented and classified numerous species, developing theories about reproduction, anatomy, and behavior. While some of his ideas were later disproven (e.g., his theory of spontaneous generation), his systematic approach to observation marked a significant step in the development of natural science.

Conclusion

Aristotle’s philosophy represents a monumental synthesis of observation, reason, and inquiry, laying the foundations for countless disciplines and shaping intellectual history across centuries. His works formed the cornerstone of medieval scholasticism, influencing thinkers like Thomas Aquinas, who integrated Aristotelian thought with Christian theology. During the Renaissance, the rediscovery of Aristotle’s writings fueled advancements in science and philosophy, with figures such as Galileo and Descartes engaging critically with his ideas.

In the modern era, Aristotle’s contributions to logic, ethics, political theory, and empirical observation remain central to philosophical inquiry and scientific methodology. His systematic approach to understanding the natural world, human behavior, and abstract principles reflects a profound commitment to intellectual rigor and curiosity. While some of his conclusions have been revised or superseded, the influence of Aristotle’s philosophy continues to inform and inspire the pursuit of knowledge.

References and further reading

- Michael Erler, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 2/2. Platon, 2007, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 978-3-7965-2237-6

- Hellmut Flashar, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 3. Ältere Akademie, Aristoteles, Peripatos, 2004, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 978-3-7965-1998-7

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics (trans. W. D. Ross), 2009, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0199213610

- Barnes, J. (Ed.), The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation, 1984, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691016511

- Lear, J., Aristotle: The Desire to Understand, 2011, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521347624

- Shields, C., Aristotle, 2013, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415622493

- Nussbaum, M. C., The Therapy of Desire: Theory and Practice in Hellenistic Ethics, 1994, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691033426

comments