Pre-Socratic natural philosophy and Thales: The shift from myth to logos

The emergence of natural philosophy in ancient Greece marks one of the most significant intellectual shifts in human history. The transition from mythological explanations of the cosmos to rational inquiry laid the foundation for philosophy and science as we know them. At the forefront of this transformation was Thales of Miletus (circa 624–546 BCE), traditionally regarded as the first philosopher in the Western tradition. Thales’ contributions represent the beginning of a profound reorientation in human thought — one that sought to understand the natural world through reason (logos) rather than myth (mythos).

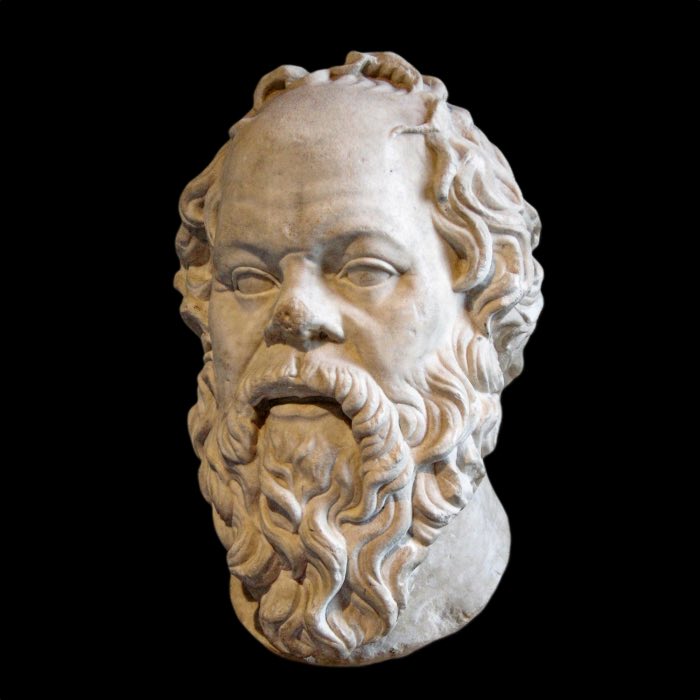

Portrait of Thales by Wilhelm Meyer, based on a bust from the 4th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Intellectual context: From mythos to logos

In early Greek culture, as in many ancient societies, myth served as the dominant framework for understanding the cosmos. Myths provided narratives that explained natural phenomena, human existence, and the structure of the universe through the actions of gods, heroes, and supernatural forces. The works of Homer and Hesiod, for instance, offered cosmological accounts rooted in divine genealogies and anthropomorphic deities.

However, by the 7th century BCE, profound socio-political and cultural changes in the Greek world created fertile ground for new ways of thinking. The rise of the polis (city-state), increasing contact with other civilizations, and the development of written language contributed to a growing curiosity about the natural world and a willingness to question traditional explanations. In this context, the pre-Socratic philosophers emerged as pioneers of rational inquiry, seeking natural rather than supernatural causes for observable phenomena.

The term logos, meaning “reason”, “word”, or “account”, encapsulates this new mode of thought. Unlike mythos, which relied on narrative and divine authority, logos emphasized logical argumentation, empirical observation, and systematic explanation. The shift from mythos to logos is not a wholesale rejection of myth but a reorientation toward a different explanatory framework, one that privileges natural causality and coherence.

Thales of Miletus: The first philosopher

Thales of Miletus, a native of the Ionian city of Miletus, stands as the first recorded thinker to apply rational inquiry to the study of the cosmos. Although no writings by Thales survive, his ideas are preserved in the works of later philosophers such as Aristotle, who credited him with initiating the tradition of natural philosophy.

Thales’ central contribution lies in his assertion that a single, underlying substance — water — constitutes the primary principle (arche) of all things. This proposition marked a radical departure from mythological cosmologies, which attributed the creation and order of the universe to the whims of gods. Instead, Thales sought to explain the diversity and change in the natural world through a unifying principle derived from observation and reason.

The arche: Water as the principle of all things

Thales’ identification of water as the arche reflects both the empirical basis of his thought and its speculative nature. Water’s pervasiveness and its role in sustaining life likely inspired Thales to see it as the fundamental substance from which all things originate. In Aristotle’s account, Thales argued that “the moist” is present in all living things, and water’s transformations — such as evaporation and condensation — demonstrate its potential to assume different forms.

This idea, while primitive by modern scientific standards, represents a significant methodological shift. By positing a material principle underlying natural phenomena, Thales replaced supernatural explanations with natural ones, laying the groundwork for scientific inquiry. His approach also implicitly assumed that the cosmos operates according to consistent and comprehensible laws, a foundational assumption of rationalism.

The cosmos: Unity and order

Thales’ cosmology extended beyond his identification of water as the arche. He is credited with asserting that the earth floats on water, an idea that, while incorrect, reflects his effort to explain the structure of the cosmos through natural principles. Moreover, Thales is said to have predicted a solar eclipse, demonstrating an ability to understand and anticipate celestial events through observation and reasoning.

Thales’ emphasis on unity and order in the cosmos resonates with the broader aims of pre-Socratic philosophy. By seeking a single principle underlying the diversity of phenomena, Thales initiated a tradition of inquiry that would culminate in metaphysical and scientific systems. His ideas about the interconnectedness of nature also foreshadow the holistic perspectives of later thinkers such as Heraclitus and the Stoics.

Thales and the concept of logos

Thales’ intellectual legacy lies not only in his specific hypotheses but also in his methodological innovations. By seeking rational explanations for natural phenomena, he established the principle of logos as a mode of inquiry. This commitment to rationality and coherence distinguished the pre-Socratic philosophers from their mythological predecessors and set the stage for the development of philosophy as a discipline.

The notion of logos would evolve in subsequent Greek thought, particularly in the works of Heraclitus, who identified logos as the universal principle governing change, and in Stoic philosophy, which equated logos with divine reason. Thales’ contributions represent the genesis of this tradition, emphasizing the intelligibility of the cosmos and the capacity of human reason to uncover its principles.

Legacy and revolutionary impact

Thales’ work marks the beginning of a profound transformation in Western human thought, one that sought to replace mythological narratives with systematic explanations based on observation, reasoning, and evidence. His identification of water as the arche and his emphasis on natural causality exemplify the shift from mythos to logos, a foundational moment in the history of Western philosophy.

While Thales’ specific hypotheses were soon superseded by more sophisticated theories, his methodological approach laid the groundwork for subsequent philosophical and scientific inquiry. The pre-Socratic philosophers who followed — such as Anaximander, Anaximenes, Heraclitus, and Parmenides — built upon Thales’ insights, exploring questions of substance, change, and being in increasingly abstract terms. Together, they established a tradition of rational inquiry that would profoundly influence later thinkers, from Plato and Aristotle to the natural philosophers of the Renaissance.

Thales’ legacy also underscores the importance of critical inquiry and intellectual curiosity in human progress. By daring to question traditional explanations and seeking new ways of understanding the world, he opened the door to a tradition of thought that continues to shape our understanding of the universe.

References and further reading

- Hellmut Flashar, Klaus Döring, Michael Erler, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 1. Frühgriechische Philosophie, 2013, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796525988

- Burnet, J., Early Greek Philosophy, 2005, Adamant Media Corporation, ISBN: 978-1402197536

- Kirk, G. S., Raven, J. E., & Schofield, M., The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts, 1983, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521274555

- Barnes, J., The Presocratic Philosophers, 1982, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415050791

- Guthrie, W. K. C., A History of Greek Philosophy, Volume 1: The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521294201

Let me know if you want ISBNs looked up or other changes!

comments