Metaphysical developments in pre-Socratic philosophy: Bridging natural philosophy and ethical inquiry

Between the early natural philosophers of Miletus and the ethical and rhetorical innovations of the Sophists and Socrates, the trajectory of Greek thought experienced a profound shift toward metaphysical speculation. This period, often associated with thinkers such as Parmenides, Empedocles, Anaxagoras, and Democritus, represents a critical phase in the evolution of philosophy. While the early Milesians focused on identifying a material principle (arche) underlying the cosmos, these later pre-Socratics extended their inquiries to explore the nature of being, causality, and the interplay of unity and plurality.

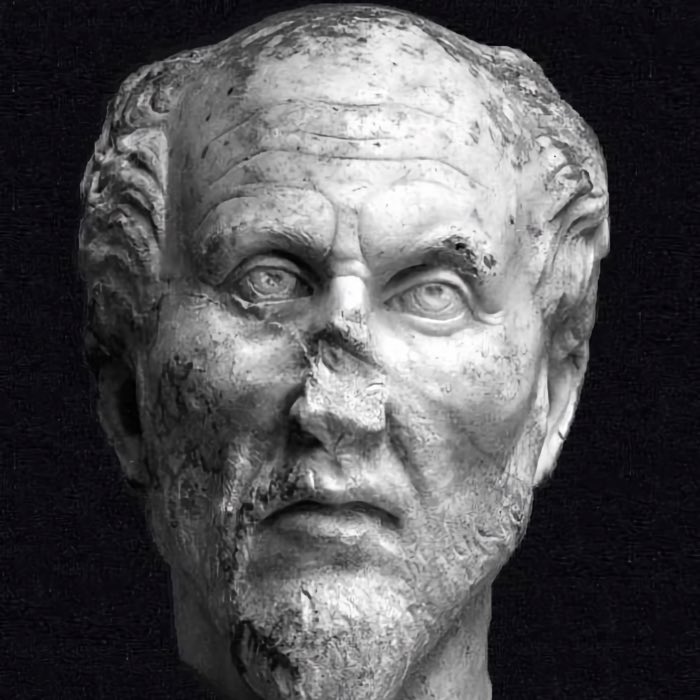

Portrait of Zeno of Elea by Jan de Bisschop (1628–1671). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

The shift toward metaphysics: From arche to being

The Milesians — Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes — were primarily concerned with identifying the arche, the underlying substance or principle from which all things arise. Their work marked the beginning of rational inquiry, emphasizing naturalistic explanations for phenomena. However, the inherent limitations of their material explanations soon became apparent, prompting subsequent thinkers to adopt a more abstract and systematic approach.

Parmenides of Elea initiated a radical departure from the Milesian tradition by asserting that true knowledge concerns being (to on) rather than the observable world of change and diversity. His distinction between the way of truth (aletheia) and the way of opinion (doxa) challenged the epistemological assumptions of earlier natural philosophy and opened new avenues for metaphysical inquiry.

Parmenides: The primacy of being and the denial of change

Parmenides’ philosophy centers on the concept of being as eternal, unchanging, and indivisible. In his poem On Nature, he argues that non-being is inconceivable and, therefore, all talk of change, motion, and plurality is illusory. According to Parmenides, the sensory world of appearances is deceptive, and true reality can only be apprehended through reason.

This radical assertion posed significant challenges to earlier cosmological theories, which depended on the assumption of dynamic processes such as generation and destruction. Parmenides’ denial of change compelled subsequent philosophers to reconcile his logical arguments with the evident diversity and transformation of the natural world.

Parmenides’ influence on metaphysics cannot be overstated. His emphasis on logical rigor and the unity of being laid the foundation for subsequent philosophical systems, including Plato’s theory of forms and Aristotle’s exploration of substance and essence.

Empedocles: Plurality and the forces of love and strife

Empedocles of Acragas sought to address the challenges posed by Parmenides by introducing a pluralistic ontology. Rather than positing a single arche or denying change altogether, Empedocles proposed that the cosmos consists of four eternal and indestructible elements — earth, air, fire, and water. These elements, he argued, combine and separate under the influence of two opposing forces: Love (philia), which unites, and Strife (neikos), which divides.

This dualistic framework allowed Empedocles to account for both the unity and diversity of the natural world. The interplay of Love and Strife creates cycles of creation and destruction, offering a dynamic vision of reality that integrates change and permanence.

Empedocles also made significant contributions to biology and the theory of perception. He proposed that all living beings share a common origin and that perception occurs through the interaction of like with like — for example, we see light because our eyes contain fire. His work reflects a synthesis of natural philosophy and metaphysics, bridging earlier materialist explanations with a more abstract understanding of causality and interaction.

Anaxagoras: Mind and the principle of order

Anaxagoras of Clazomenae advanced the metaphysical project by introducing the concept of nous (mind or intellect) as the organizing principle of the cosmos. Rejecting the idea of a single arche or even a fixed set of elements, Anaxagoras posited an infinite number of fundamental particles (seeds or homoiomeries), each containing a portion of every other substance.

According to Anaxagoras, these particles are set in motion and arranged by nous, an infinite, autonomous, and purposeful force. Nous is not a material substance but a metaphysical principle, capable of initiating motion and imposing order on the chaotic mixture of particles. This idea represents one of the earliest articulations of a dualistic framework, distinguishing between material and immaterial causes.

Anaxagoras’ emphasis on nous as a rational and purposeful force foreshadows later philosophical developments, particularly in Plato’s and Aristotle’s accounts of teleology and causation. His work also reflects a growing interest in the relationship between mind and matter, a theme that continues to resonate in modern philosophy and science.

Democritus: Atomism and the nature of reality

Democritus of Abdera, along with his teacher Leucippus, developed the theory of atomism, offering a materialist response to the metaphysical challenges posed by Parmenides. Atomism posits that the cosmos consists of indivisible, eternal atoms moving through the void. These atoms differ in size, shape, and arrangement, and their interactions account for the observable diversity of phenomena.

For Democritus, change and motion are not illusions but arise from the rearrangement of atoms. By introducing the void as a necessary condition for motion, he reconciled the apparent contradiction between Parmenides’ emphasis on being and the observable reality of change.

Atomism also incorporates a naturalistic explanation of perception, thought, and the soul. Democritus argued that the soul consists of fine, spherical atoms that move freely within the body, enabling sensation and cognition. This materialist account challenges earlier metaphysical theories by rejecting immaterial or supernatural explanations.

Democritus’ atomism profoundly influenced subsequent scientific and philosophical traditions, from Epicureanism to modern physics. His commitment to naturalistic explanations and his emphasis on causality and determinism represent a significant departure from earlier speculative metaphysics.

The unifying themes of metaphysical developments

The metaphysical developments of this period reflect a shared concern with reconciling the unity of being with the diversity and dynamism of the natural world. Each thinker addressed this challenge in a distinct way: Parmenides emphasized the eternal and unchanging nature of being; Empedocles introduced plurality and cyclical forces; Anaxagoras posited a rational principle of order; and Democritus advanced a materialist theory of atoms and the void.

These contributions mark a critical transition from early natural philosophy to the more systematic metaphysical frameworks of Plato and Aristotle. They also demonstrate an increasing abstraction in philosophical thought, as thinkers moved beyond the identification of material principles to explore the fundamental structures and causes of reality.

Conclusion

The period of metaphysical developments in pre-Socratic philosophy represents a pivotal moment in the history of Western thought. By addressing questions of being, causality, and the nature of reality, Parmenides, Empedocles, Anaxagoras, and Democritus laid the intellectual foundations for classical metaphysics and science. Their diverse approaches reflect a rich and dynamic tradition of inquiry, bridging the naturalistic focus of earlier philosophy with the ethical and epistemological concerns that would dominate the classical period.

References and further reading

- Hellmut Flashar, Klaus Döring, Michael Erler, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 1. Frühgriechische Philosophie, 2013, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796525988

- Burnet, J., Early Greek Philosophy, 2005, Adamant Media Corporation, ISBN: 978-1402197536

- Kirk, G. S., Raven, J. E., & Schofield, M., The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts, 1983, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521274555

- Barnes, J., The Presocratic Philosophers, 1982, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415050791

- Guthrie, W. K. C., A History of Greek Philosophy, Volume 1: The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521294201

- Longrigg, J., Greek Rational Medicine: Philosophy and Medicine from Alcmaeon to the Alexandrians, 2013, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415861977

- Graham, D. W., Explaining the Cosmos: The Ionian Tradition of Scientific Philosophy, 2006, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691125404

comments