Heraclitus: The philosopher of change and the logos

Heraclitus of Ephesus (circa 535–475 BCE) stands as one of the most enigmatic and influential figures of early Greek philosophy. Known as the “philosopher of flux” (pánta rheî, “everything flows”), Heraclitus developed a vision of reality grounded in the principles of perpetual change, opposition, and unity. His aphoristic and often cryptic statements — many of which survive only as fragments — challenge conventional thinking and emphasize the dynamic interplay of order and chaos, the finite and the infinite. Central to Heraclitus’ thought is the concept of the logos (reason, word, or principle), which he saw as the underlying structure of the cosmos, governing its constant transformations.

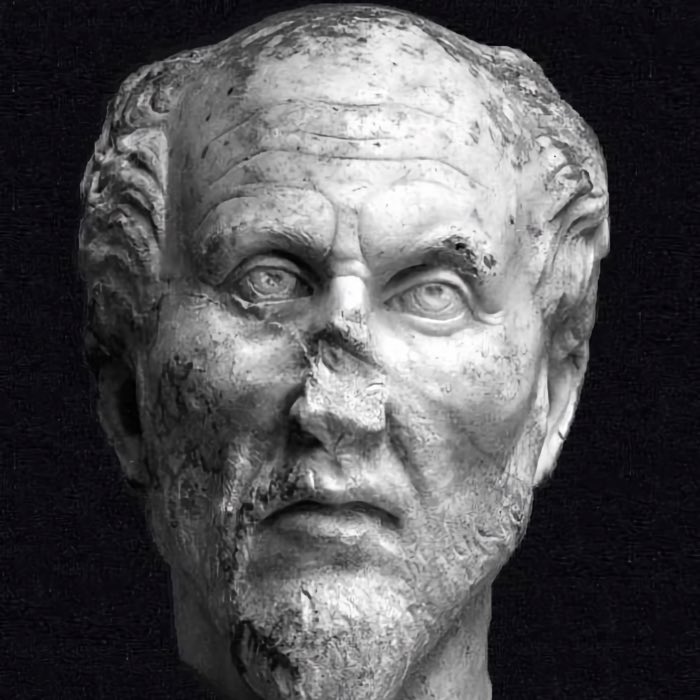

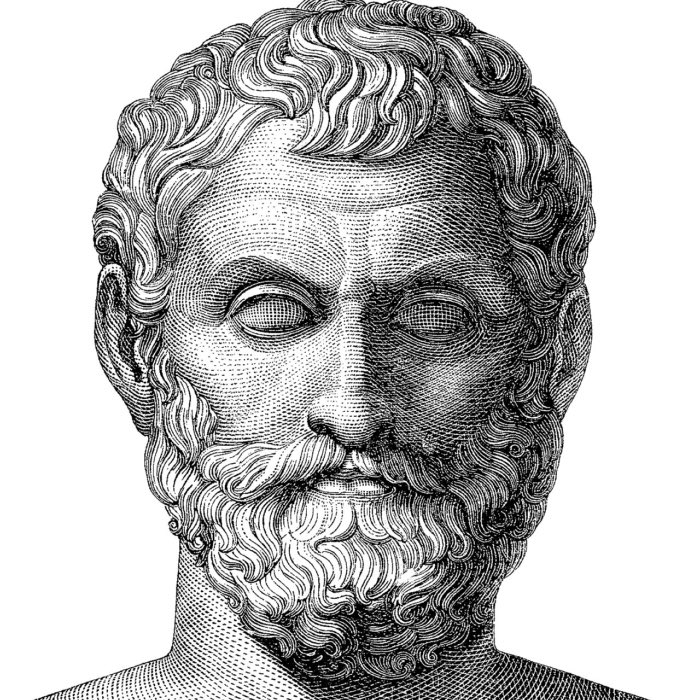

Bust of Heraclitus by Giuseppe Torretti (1705). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Heraclitus’ ideas have had a profound impact on the development of Western philosophy, influencing thinkers from the Stoics and Neoplatonists to modern existentialists and process philosophers. By examining his metaphysical, cosmological, and ethical insights, we gain a deeper understanding of his revolutionary contributions to the history of thought.

The doctrine of flux: “Panta Rhei”

One of Heraclitus’ most famous assertions is that “everything flows” (panta rhei). This doctrine of flux encapsulates his view that the cosmos is in a state of constant change. For Heraclitus, nothing remains static; all things are in a process of becoming, emerging and dissolving in a continuous cycle.

The metaphor of the river, found in several of his fragments, illustrates this principle. Heraclitus is often paraphrased as saying, “You cannot step into the same river twice”, because the waters are ever-changing. However, some interpretations suggest a more nuanced meaning: the river, as a dynamic entity, maintains its identity precisely because of its perpetual motion. This insight emphasizes the tension between change and stability, suggesting that identity and continuity arise from the process of transformation itself.

Heraclitus’ emphasis on flux challenges the static metaphysical models of earlier thinkers, such as Parmenides, who posited the unchanging nature of being. For Heraclitus, reality is defined not by stasis but by the interdependent processes of creation and destruction, which he saw as essential to the cosmos’ order and vitality.

Unity of opposites

A central theme in Heraclitus’ philosophy is the unity of opposites. He argued that seemingly contradictory forces are, in fact, complementary and interdependent. This idea is captured in fragments such as:

“War is the father of all things”, and, “The way up and the way down are one and the same.”

For Heraclitus, opposites are not mutually exclusive but rather aspects of a greater unity. Day and night, life and death, growth and decay — all are part of a dynamic interplay that defines existence. This principle extends to the human experience, where joy and sorrow, success and failure, are interconnected aspects of life’s continuous flux.

The unity of opposites is central to Heraclitus’ cosmology, as it provides the mechanism by which the cosmos achieves balance and harmony. Far from viewing conflict as destructive, Heraclitus saw it as the engine of creativity and order, a necessary force that sustains the dynamic equilibrium of the universe.

The logos: The rational order of the cosmos

The concept of the logos is perhaps Heraclitus’ most enduring contribution to philosophy. He conceived the logos as the universal principle that governs and unites all things. While the logos is immanent in the cosmos, it also transcends individual phenomena, serving as the rational order that underlies perpetual change.

Heraclitus emphasized that the logos is accessible to human understanding, but he lamented that most people fail to recognize or comprehend it. In one of his fragments, he declares:

“Although the logos is common to all, most people live as if they had their own private understanding.”

This critique highlights Heraclitus’ view of human ignorance and his call for aligning oneself with the logos through rational inquiry and reflection. For Heraclitus, the logos is not only a cosmic principle but also an ethical guide, providing a framework for living in harmony with the natural order.

The Stoics later developed Heraclitus’ concept of the logos into a fully articulated doctrine, equating it with divine reason and the organizing principle of the universe. In this sense, Heraclitus’ influence extends far beyond his own time, shaping subsequent metaphysical and theological thought.

Fire as the archetype of change

Heraclitus identified fire as the fundamental element and metaphor for the cosmos’ constant transformation. Unlike earlier philosophers, such as Thales and Anaximenes, who posited water or air as the arche (primary substance), Heraclitus chose fire because of its dynamic and ephemeral nature. Fire consumes and transforms, creating new forms while destroying old ones, embodying the perpetual flux that defines reality.

Fire, for Heraclitus, is not merely a physical element but a symbol of the process through which opposites interact and balance. It represents the energy and motion that drive the cosmos, aligning with his broader metaphysical vision of change as the essence of existence.

Ethics and human life

Heraclitus’ philosophy extends beyond cosmology to encompass profound ethical insights. He argued that human life is inseparable from the cosmic order and that individuals must align their actions with the logos. By recognizing the unity of opposites and the necessity of change, one can attain wisdom and live in harmony with the natural world.

Heraclitus viewed human folly as a failure to grasp the logos and the interconnectedness of all things. His critique of human ignorance is evident in fragments such as:

“The eyes are more accurate witnesses than the ears”, and, “Many who hear do not understand.”

These statements reflect his emphasis on direct experience and rational understanding as paths to wisdom. Heraclitus’ ethical philosophy calls for humility, self-awareness, and a commitment to reason as the means of navigating life’s complexities.

Influence and legacy

Heraclitus’ ideas have had a profound and far-reaching influence on the history of philosophy. His concept of flux challenged early metaphysical systems and inspired subsequent debates about the nature of reality, identity, and change. The unity of opposites and the logos became central themes in Stoic philosophy, while his emphasis on the dynamic interplay of forces resonates with modern process philosophy and existentialism.

Heraclitus’ thought also influenced later metaphysical systems, including Neoplatonism and early Christian theology. The logos as a principle of cosmic order found echoes in the Gospel of John, where it is equated with the divine Word. This reinterpretation underscores Heraclitus’ enduring relevance as a thinker whose insights transcend cultural and historical boundaries.

In the modern era, Heraclitus’ philosophy continues to inspire thinkers in fields ranging from physics to literature. His vision of a world defined by constant change and interconnectedness offers a profound lens through which to understand the complexities of existence, challenging static and reductionist models of reality.

Conclusion

Heraclitus of Ephesus stands as a foundational figure in the history of Western philosophy, offering a vision of reality that emphasizes perpetual change, the unity of opposites, and the rational order of the cosmos. His concept of the logos and his doctrine of flux challenge conventional thinking, inviting us to embrace the dynamic and interdependent nature of existence. By synthesizing metaphysical, cosmological, and ethical insights, Heraclitus provides a framework for understanding the world that remains as relevant today as it was in ancient Greece.

References and further reading

- Hellmut Flashar, Klaus Döring, Michael Erler, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 1. Frühgriechische Philosophie, 2013, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796525988

- Burnet, J., Early Greek Philosophy, 2005, Adamant Media Corporation, ISBN: 978-1402197536

- Kirk, G. S., Raven, J. E., & Schofield, M., The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts, 1983, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521274555

- Barnes, J., The Presocratic Philosophers, 1982, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415050791

- Guthrie, W. K. C., A History of Greek Philosophy, Volume 1: The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521294201

comments