Democritus: The father of atomism and the materialist worldview

Democritus of Abdera (circa 460–370 BCE) stands as one of the most significant figures in ancient Greek philosophy and the history of science. Building on the work of his teacher Leucippus, Democritus developed the first systematic theory of atomism, positing that all phenomena in the universe arise from the interactions of indivisible, eternal particles (atoms) moving through the void. His materialist and deterministic worldview represented a radical departure from earlier metaphysical systems, challenging traditional notions of divine causality and emphasizing natural explanations for the diversity and complexity of existence.

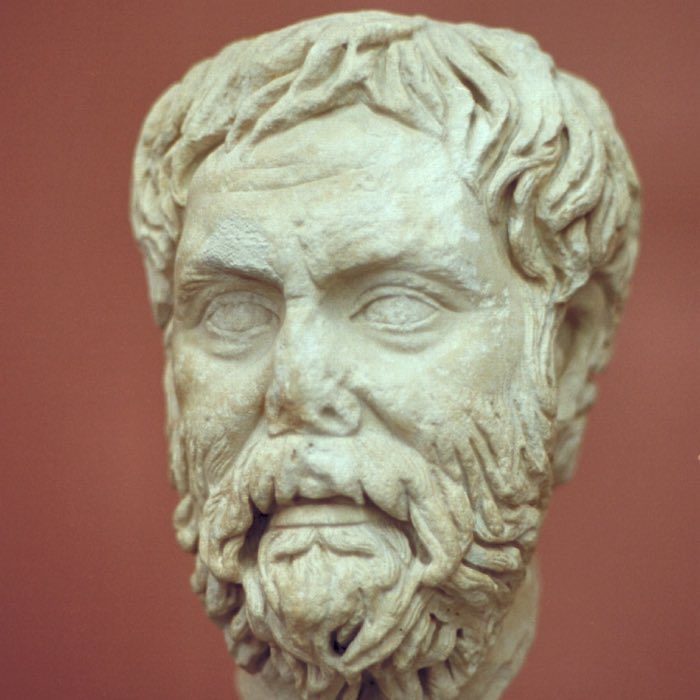

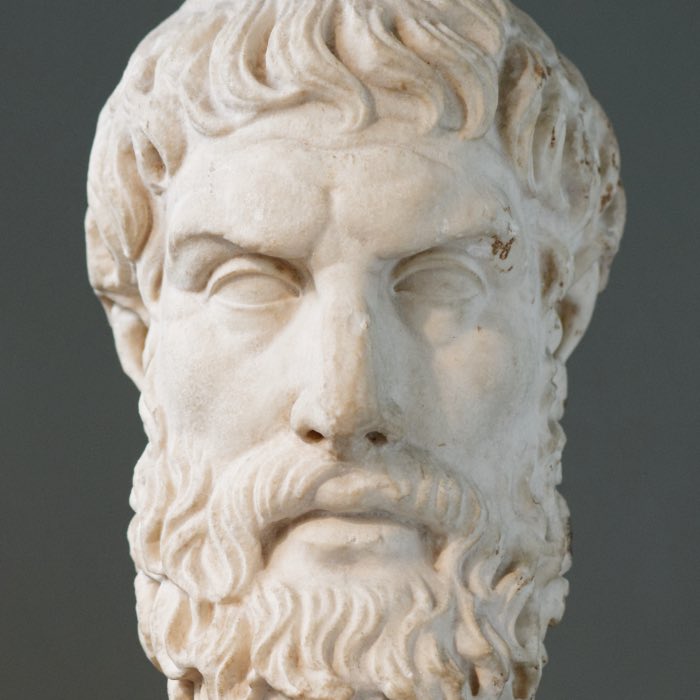

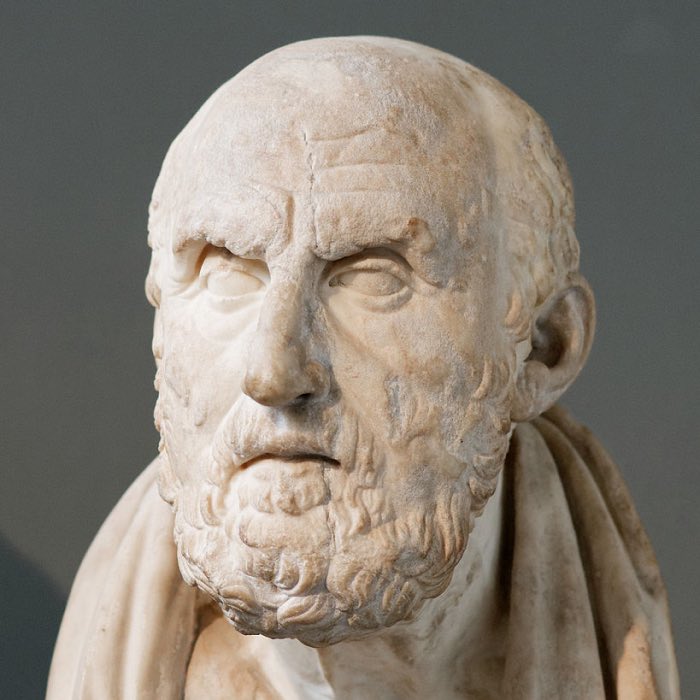

Bust of Democritus from 2020 presented to the International Atomic Energy Agency by Greece. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Democritus’ philosophy, preserved through fragments and the accounts of later authors, is remarkable for its breadth, encompassing not only cosmology and physics but also ethics, epistemology, and aesthetics. Although his ideas were marginalized in the classical period due to the dominance of Platonic and Aristotelian thought, they resurfaced in the Renaissance and Enlightenment, profoundly influencing the development of modern science.

Atomism: The fundamental theory of reality

At the heart of Democritus’ philosophy is the theory of atomism, which posits that the universe consists of two fundamental realities: atoms and the void. Atoms are indivisible, indestructible, and infinite in number and variety. They differ in size, shape, and arrangement but are otherwise homogeneous, lacking internal structure. The void, an infinite expanse of empty space, provides the medium in which atoms move and interact.

Democritus proposed that all observable phenomena arise from the motion and combinations of atoms. Objects differ from one another not because of the intrinsic properties of their constituent atoms but because of the specific arrangements and configurations of these atoms. For example, the hardness of a diamond and the softness of clay result from the differing densities and arrangements of their atomic structures.

The motion of atoms is governed by necessity, with no role for divine intervention or teleological purpose. Atoms collide, combine, and separate according to deterministic laws, creating the world as a vast and dynamic system of interactions. This mechanistic view of the cosmos marked a significant departure from earlier metaphysical frameworks, which often relied on supernatural or anthropomorphic explanations.

The void and the problem of motion

One of the most innovative aspects of Democritus’ atomism is his concept of the void. Previous philosophers, particularly Parmenides and Zeno, had denied the existence of empty space, arguing that it was logically incoherent. Democritus, by contrast, asserted that the void is as real as atoms themselves and is essential for motion and change.

The void allows atoms to move freely, enabling the formation of compounds and the dynamic processes of the natural world. Without the void, atoms would be static and unchanging, and the diversity of phenomena would be inexplicable. This idea reconciles the Eleatic emphasis on the permanence of being with the observable reality of motion and transformation, bridging a critical gap in pre-Socratic philosophy.

Cosmology: The infinite worlds

Democritus extended his atomistic theory to cosmology, proposing that the universe is infinite in extent and contains countless worlds. These worlds differ in size, composition, and structure, some being inhabited and others devoid of life. The formation of worlds, he argued, occurs through the random motion and aggregation of atoms, without any guiding intelligence or predetermined design.

This cosmological vision reflects Democritus’ commitment to naturalistic explanations and his rejection of anthropocentric and teleological models. By situating humanity within an infinite and impersonal cosmos, Democritus challenged the traditional Greek worldview, which often placed human beings at the center of divine purpose.

Epistemology: Knowledge and the senses

Democritus developed a sophisticated theory of knowledge that distinguishes between two levels of perception: bastard knowledge, derived from the senses, and legitimate knowledge, attained through reason. He recognized that sensory perception is limited and often deceptive, providing only a superficial understanding of the world. For example, the qualities we perceive — such as color, taste, and temperature — do not exist in the atoms themselves but arise from the interactions between atoms and our sensory organs.

Legitimate knowledge, according to Democritus, involves reasoning about the underlying atomic structure of reality. By understanding the principles of atomism, one can uncover the true nature of the cosmos and transcend the illusions of the senses. This epistemological framework emphasizes the importance of rational inquiry and systematic thought, anticipating later developments in scientific methodology.

Ethics: The pursuit of eudaimonia

Democritus’ ethical philosophy, like his cosmology, is grounded in materialism and rationalism. He argued that the highest good for human beings is eudaimonia (flourishing or happiness), which he defined as a state of inner tranquility and harmony. Unlike hedonists who equated happiness with sensory pleasure, Democritus emphasized the role of reason, self-discipline, and moral virtue in achieving a fulfilling life.

Central to his ethics is the concept of euthymia (cheerfulness or well-being), which arises from moderation, intellectual inquiry, and the avoidance of excessive desires and passions. Democritus viewed the pursuit of wisdom as essential to human flourishing, asserting that understanding the natural world leads to a greater sense of purpose and contentment.

Democritus also advocated for ethical behavior grounded in social harmony and mutual respect. He argued that justice and fairness are essential for a stable and cooperative society, reflecting his belief in the interconnectedness of individuals and their shared responsibilities.

Aesthetics: The Harmony of form and function

Democritus’ philosophy extends to aesthetics, where he explored the nature of beauty and its relationship to proportion and harmony. He believed that beauty arises from the orderly arrangement of parts, whether in art, nature, or human behavior. This idea aligns with his atomistic worldview, which emphasizes the importance of structure and organization in creating complex and harmonious systems.

Democritus also valued the role of art and intellectual pursuits in cultivating the mind and enhancing human experience. His reflections on aesthetics demonstrate his holistic approach to philosophy, integrating physical, ethical, and artistic dimensions into a unified vision of life.

Influence and legacy

Democritus’ atomism had a profound impact on the development of natural philosophy and science. While his ideas were overshadowed in antiquity by the metaphysical systems of Plato and Aristotle, they were preserved through the works of later thinkers, including Epicurus and Lucretius. The revival of atomism during the Renaissance and Enlightenment, particularly in the works of Galileo, Descartes, and Newton, owes much to the foundational principles established by Democritus.

Modern atomic theory, though vastly different in detail, reflects the spirit of Democritus’ inquiry, emphasizing the role of fundamental particles and natural laws in explaining the complexity of the universe. His materialist and mechanistic worldview laid the groundwork for the scientific revolution and continues to inform contemporary debates in physics, chemistry, and philosophy.

Conclusion

Democritus of Abdera represents a pivotal moment in the history of philosophy, offering a comprehensive and naturalistic account of reality that challenges traditional metaphysical and theological frameworks. His theory of atomism, grounded in the principles of indivisibility, necessity, and motion, provides a powerful explanatory model for the diversity and complexity of the cosmos. By integrating physical, epistemological, ethical, and aesthetic insights, Democritus created a unified philosophical system that remains relevant to this day. His legacy as the “father of atomism” underscores the importance of rational inquiry in the quest to understand the universe.

References and further reading

- Hellmut Flashar, Klaus Döring, Michael Erler, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 1. Frühgriechische Philosophie, 2013, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796525988

- Burnet, J., Early Greek Philosophy, 2005, Adamant Media Corporation, ISBN: 978-1402197536

- Kirk, G. S., Raven, J. E., & Schofield, M., The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts, 1983, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521274555

- Barnes, J., The Presocratic Philosophers, 1982, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415050791

- Guthrie, W. K. C., A History of Greek Philosophy, Volume 1: The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521294201

- Graham, D. W., Explaining the Cosmos: The Ionian Tradition of Scientific Philosophy, 2006, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691125404

- Kingsley, P., Ancient Philosophy, Mystery, and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition, 1997, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0198150817

- Long, A. A., The Cambridge Companion to Early Greek Philosophy, 1999, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521446679

- Taylor, C. C. W., The Atomists: Leucippus and Democritus, 2010, University of Toronto Press, ISBN: 978-1442612129

comments