Anaximenes: The philosopher of air and the continuity of nature

Anaximenes of Miletus (circa 586–526 BCE), the third and youngest of the early Milesian philosophers, is a pivotal figure in the development of pre-Socratic natural philosophy. Building upon the inquiries of his predecessors, Thales and Anaximander, Anaximenes sought to refine the search for the arche (the primary principle or substance of all things) by proposing air as the fundamental substance underlying all existence. His work represents an important stage in the evolution of Greek thought, as it combines empirical observation with a systematic explanation of natural phenomena, moving toward a more refined understanding of the processes governing the cosmos.

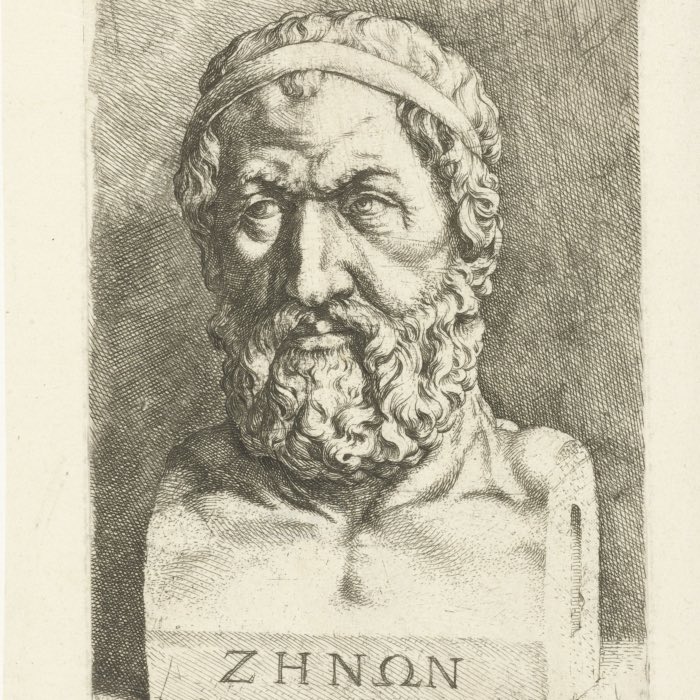

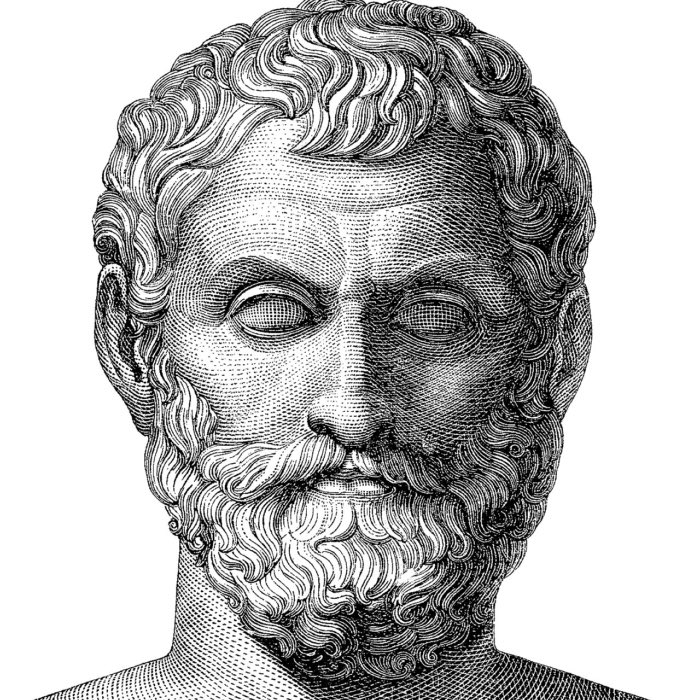

Anaximenes of Miletus as imaginatively depicted, wearing a tainia, in a 16th-century engraving from Girolamo Olgiati. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Although Anaximenes’ writings have not survived, his ideas are preserved through the accounts of later philosophers, including Aristotle, Theophrastus, and Simplicius. His philosophy is distinguished by its focus on the mechanisms of transformation, as well as its attempt to unify diverse phenomena under a single explanatory framework.

The arche: Air as the principle of all things

Anaximenes continued the Milesian tradition of seeking a material substance as the ultimate arche. While Thales identified water and Anaximander proposed the abstract apeiron (the infinite or boundless), Anaximenes chose air (aer) as the primary substance from which all things arise. He argued that air, being both infinite and perceptible, is a fitting candidate for the arche because of its ability to transform into other forms of matter.

For Anaximenes, air is the life-giving force that sustains both the cosmos and individual organisms. Its omnipresence and essential role in breathing (which he likely associated with the soul, or psyche) made it an intuitive choice as the fundamental principle. Anaximenes’ identification of air as the arche represents an effort to bridge the tangible and the abstract, combining sensory experience with metaphysical reasoning.

Processes of transformation: Rarefaction and condensation

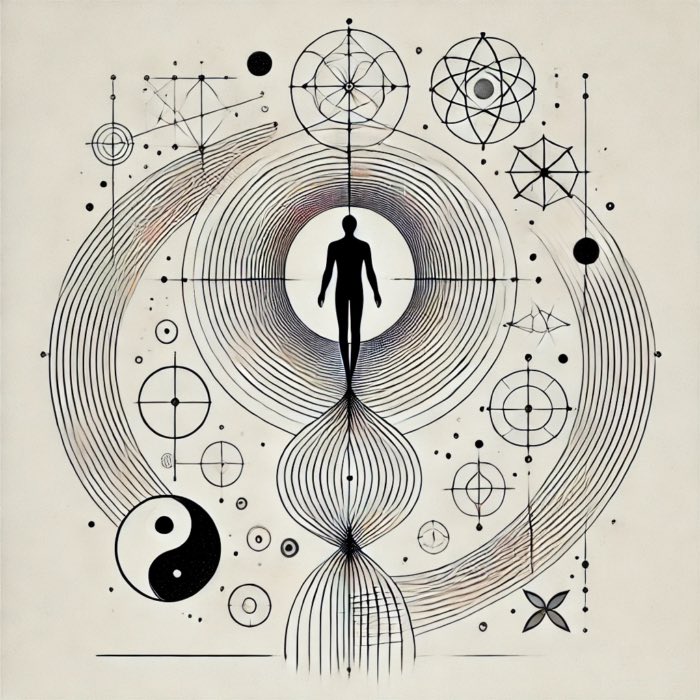

One of Anaximenes’ most innovative contributions to pre-Socratic philosophy is his explanation of how air transforms into other forms of matter. He proposed that changes in the density of air, through the processes of rarefaction and condensation, account for the diversity of phenomena in the natural world. Rarefaction produces lighter substances, such as fire, while condensation leads to denser forms, such as water, earth, and stone.

This theory of transformation marks a significant advance in natural philosophy. By introducing a mechanism to explain how one substance can give rise to many, Anaximenes provided a framework for understanding the dynamic and interconnected nature of the cosmos. His emphasis on continuity and gradual change contrasts with Anaximander’s notion of opposites in conflict, offering an alternative model of cosmic balance and unity.

Cosmology: The structure and dynamics of the universe

Anaximenes applied his principle of air to develop a comprehensive cosmology, offering explanations for the formation and behavior of celestial bodies, weather, and other natural phenomena. He envisioned the earth as a flat disc supported by air, floating like a leaf on water. The sun, moon, and stars, according to Anaximenes, are composed of fiery matter and are carried by currents of air.

One of his key insights was the idea that natural phenomena are governed by physical processes rather than divine intervention. For instance, he attributed rain and clouds to the condensation of air and explained the formation of wind as the result of moving air. While these explanations were often speculative, they represent a significant departure from mythological accounts, emphasizing the role of natural laws and observable processes.

Anaximenes’ cosmological model also reflects an early attempt to unify terrestrial and celestial phenomena under a single explanatory system. By applying the principle of air and its transformations to both the heavens and the earth, he reinforced the idea that the cosmos operates as a coherent and interconnected whole.

The role of air in life and soul

Anaximenes’ choice of air as the arche was likely influenced by its association with life and vitality. In many ancient cultures, breath and air were closely linked to the concept of the soul (psyche) and the essence of life. Anaximenes extended this connection to the cosmos, suggesting that just as air sustains individual organisms, it also animates and sustains the universe as a whole.

This idea foreshadows later philosophical and religious traditions that associate a fundamental, invisible substance with both life and the divine. The Stoic concept of the logos as a rational, animating force shares affinities with Anaximenes’ notion of air as the underlying principle of order and vitality.

Anaximenes in the context of pre-Socratic philosophy

Anaximenes occupies a critical place in the evolution of pre-Socratic thought. By emphasizing observable processes and proposing a material substance as the arche, he maintained the Milesian focus on naturalism while advancing a more systematic approach to explaining change and diversity. His theory of rarefaction and condensation, in particular, represents an early effort to account for the mechanisms underlying the transformation of matter, paving the way for later developments in natural philosophy and science.

Anaximenes’ work also highlights the tension between empiricism and abstraction that characterizes pre-Socratic philosophy. While his choice of air reflects a reliance on sensory experience, his conceptualization of its transformations introduces a level of abstraction that anticipates later metaphysical inquiries. This dual emphasis on observation and reasoning would become a hallmark of Greek philosophical thought.

Legacy and influence

Anaximenes’ contributions to natural philosophy had a lasting impact on the trajectory of Greek thought. His emphasis on continuity and transformation influenced later philosophers, including Heraclitus, who explored the dynamic nature of reality, and the atomists, who sought to explain the diversity of phenomena through the interactions of fundamental particles.

The ruins of Miletus. Miletus is a city of ancient Ionia, near the mouth of the Meander River in what is now Turkey. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

In addition, Anaximenes’ focus on physical processes and material explanations contributed to the development of the scientific method. By seeking natural causes for natural phenomena, he helped establish the principle that the universe operates according to intelligible and consistent laws.

Anaximenes’ ideas also resonate with modern scientific concepts, such as the conservation of matter and the role of gases in sustaining life and the environment. While his specific theories were eventually superseded, his commitment to understanding the natural world through observation and reasoning remains a cornerstone of scientific inquiry.

Conclusion

Anaximenes of Miletus represents a vital link in the chain of pre-Socratic philosophy, building upon the insights of Thales and Anaximander while introducing new concepts and methods that shaped the course of Greek thought. His identification of air as the arche and his theory of rarefaction and condensation reflect a profound attempt to explain the unity and diversity of the cosmos through natural processes. By integrating empirical observation with abstract reasoning, Anaximenes laid the groundwork for the scientific and philosophical traditions that followed, exemplifying the transformative power of rational inquiry.

References and further reading

- Hellmut Flashar, Klaus Döring, Michael Erler, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 1. Frühgriechische Philosophie, 2013, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796525988

- Burnet, J., Early Greek Philosophy, 2005, Adamant Media Corporation, ISBN: 978-1402197536

- Kirk, G. S., Raven, J. E., & Schofield, M., The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts, 1983, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521274555

- Barnes, J., The Presocratic Philosophers, 1982, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415050791

- Guthrie, W. K. C., A History of Greek Philosophy, Volume 1: The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521294201

comments