Anaximander: Pioneer of cosmology and natural philosophy

Anaximander of Miletus (c. 610–546 BCE), a successor of Thales and a pivotal figure in early Greek philosophy, stands out as one of the first thinkers to grapple with the structure and origins of the cosmos through systematic reasoning. His work represents a significant advance in the intellectual project initiated by his predecessor, moving beyond the identification of a single material principle to explore abstract and metaphysical explanations of existence. Anaximander’s contributions to cosmology, geography, biology, and metaphysics not only expanded the horizons of early Greek thought but also laid the groundwork for the development of science and philosophy.

Ancient Roman mosaic from Johannisstraße, Trier, dating to the early third century CE, showing Anaximander holding a sundial. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Although none of Anaximander’s writings survive in their entirety, fragments of his ideas are preserved in the works of later authors, such as Aristotle, Theophrastus, and Simplicius. These fragments, along with historical accounts, reveal a thinker whose inquiries transcended mere observation to address profound questions about the nature of reality, the origins of the cosmos, and the principles governing natural phenomena.

The apeiron: The infinite and indeterminate principle

Anaximander’s most significant philosophical contribution lies in his concept of the apeiron (ἄπειρον), a term meaning “infinite” or “boundless.” Unlike Thales, who identified water as the primary substance (arche) of the cosmos, Anaximander proposed that the underlying principle of all things is the apeiron, an eternal, indeterminate, and infinite substance. This abstraction marked a decisive shift in early Greek thought, moving beyond tangible elements to a metaphysical foundation.

The apeiron, according to Anaximander, is the source of all things and encompasses the origins, transformations, and eventual dissolution of phenomena. It is eternal and self-regulating, generating the cosmos through a dynamic process of separation and opposition. For example, the interplay of opposites such as hot and cold, wet and dry, is central to his cosmology, reflecting the inherent tension and balance within the apeiron.

By positing the apeiron as the ultimate principle, Anaximander introduced a radical idea: that the cosmos is governed by an abstract, impersonal force rather than by divine beings or anthropomorphic deities. This notion foreshadowed later philosophical explorations of the infinite and the uncaused cause in metaphysics.

Cosmology and the origins of the universe

Anaximander’s cosmological theories further illustrate his innovative approach to understanding the natural world. He proposed that the cosmos originated from the apeiron through a process of differentiation, whereby opposites emerged and gave rise to the elements. From these elements, the heavens, earth, and all living beings were formed.

In his view, the earth is a cylindrical body suspended freely in space, equidistant from all other celestial objects. This idea, revolutionary for its time, challenged earlier notions of a flat or supported earth. Anaximander reasoned that the earth’s stability arises from its position at the center of the cosmos, a concept that introduced the principle of equilibrium — a precursor to later developments in physics.

Anaximander also hypothesized about the structure of the heavens, suggesting that celestial bodies are rings of fire encased in opaque shells, with holes through which their light emerges. While this model was eventually superseded, it demonstrates his willingness to propose bold and systematic explanations for natural phenomena.

The eternal cycle of creation and destruction

A defining feature of Anaximander’s thought is his conception of the cosmos as governed by a cyclical process of creation and destruction. He argued that all things arise from the apeiron and ultimately return to it, maintaining a balance in the natural order. This cyclical view extends to his understanding of justice (dike) in the cosmos, a principle that ensures equilibrium among opposing forces.

In one of the surviving fragments attributed to him, Anaximander states:

“Things perish into that from which they have their origin, according to necessity; for they pay penalty and retribution to each other for their injustice, according to the order of time.”

This notion of cosmic justice reflects a profound metaphysical insight: that the natural world operates according to laws of necessity and balance, independent of human or divine intervention. It marks a departure from mythological explanations and paves the way for later philosophical investigations into causality and ethics.

Contributions to geography and biology

Anaximander’s inquiries extended beyond cosmology to include pioneering work in geography and biology. He is credited with producing one of the earliest maps of the known world, which depicted the earth as a flat, cylindrical surface surrounded by a vast ocean. While his geographical knowledge was limited, his efforts represent an early attempt to systematically represent the natural world.

Possible rendering of Anaximander’s world map. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

In biology, Anaximander proposed that life originated in water and that humans evolved from aquatic creatures. He observed the dependency of human infants on prolonged care, leading him to speculate that humans must have evolved from other animals capable of surviving independently at birth. Although speculative, these ideas highlight his commitment to explaining natural phenomena through observation and rational inference.

Legacy and influence

Anaximander’s contributions to natural philosophy represent a critical moment in the history of thought, bridging the mythological worldview of early Greek culture and the rationalist tradition that would culminate in the works of later philosophers such as Heraclitus, Parmenides, and Aristotle. His abstraction of the apeiron as the ultimate principle of existence opened new avenues for metaphysical inquiry, while his cosmological theories demonstrated the power of systematic reasoning in addressing fundamental questions about the universe.

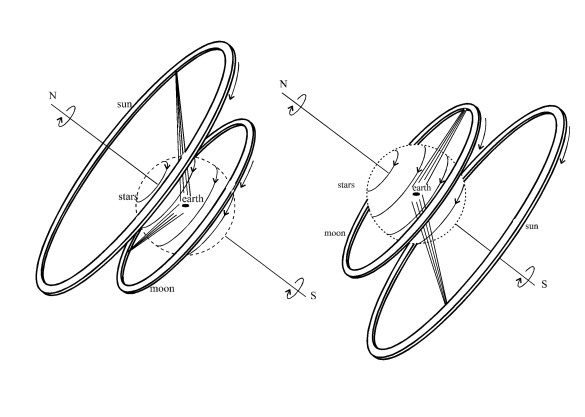

Illustration of Anaximander’s models of the universe. On the left, daytime in summer; on the right, nighttime in winter. Note the sphere represents the combined rings of all of the stars about the very small inner cylinder which represents the Earth. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Moreover, Anaximander’s emphasis on the balance of opposites and the cyclical nature of reality influenced subsequent philosophical and scientific traditions. The Stoics, for example, adopted similar ideas about the interplay of opposites and the eternal recurrence of cosmic processes, while Aristotle’s metaphysics and natural philosophy reflect echoes of Anaximander’s insights into causality and the infinite.

Anaximander’s legacy also extends to the history of science, as his efforts to explain natural phenomena through observation and reason anticipate the methodologies of modern scientific inquiry. While many of his specific theories were eventually replaced, his pioneering spirit and intellectual courage continue to inspire philosophers and scientists alike.

Conclusion

Anaximander of Miletus occupies a pivotal place in the history of philosophy as one of the first thinkers to propose abstract, systematic explanations for the origins and structure of the cosmos. His concept of the apeiron and his cosmological theories represent a bold departure from the mythological traditions of his time, laying the foundations for metaphysics and natural science. By seeking to understand the universe through rational inquiry, Anaximander exemplifies the transformative power of human thought in its quest to uncover the principles underlying existence.

References and further reading

- Hellmut Flashar, Klaus Döring, Michael Erler, Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 1. Frühgriechische Philosophie, 2013, Schwabe, Aus der Reihe: Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, ISBN: 9783796525988

- Burnet, J., Early Greek Philosophy, 2005, Adamant Media Corporation, ISBN: 978-1402197536

- Kirk, G. S., Raven, J. E., & Schofield, M., The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts, 1983, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521274555

- Barnes, J., The Presocratic Philosophers, 1982, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415050791

- Guthrie, W. K. C., A History of Greek Philosophy, Volume 1: The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans, 2010, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521294201

comments