Zoroastrianism: A revolutionary faith of ancient Iran

Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest organized religions, was founded by the prophet Zarathushtra (Greek: Zoroaster) in ancient Iran, likely during the second millennium BCE. Emerging in a polytheistic and ritual-dominated environment, Zoroastrianism introduced a revolutionary religious framework centered on moral dualism, ethical monotheism, and the responsibility of individual choice. Zarathushtra’s teachings, preserved in the sacred texts of the Avesta, laid the foundation for a faith that would profoundly influence not only Iranian culture but also the development of later world religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and elements of Indian spirituality.

3rd-century Mithraic depiction of Zoroaster found in Dura Europos, Syria. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

At its height during the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE), Zoroastrianism served as the state religion and guided the philosophical and ethical principles of Persian governance. Though its prominence waned after the Islamic conquest of Persia in the 7th century CE, Zoroastrianism endures among small communities in Iran, India (Parsis), and the diaspora. The religion’s core beliefs, practices, and legacy continue to be studied for their historical significance and impact on global religious traditions.

Zarathushtra: The prophet and his revelation

The historical figure of Zarathushtra is shrouded in mystery, with scholars debating his exact dates and origins. Most estimates place his life between 1200 and 600 BCE, although earlier datings are also considered. Zarathushtra is traditionally believed to have been born in eastern Iran or Central Asia into a priestly family. His spiritual awakening led him to reject the ritualistic and polytheistic practices of his time, offering instead a vision of a single, supreme deity — Ahura Mazda — and a moral universe governed by the principles of truth (asha) and falsehood (druj).

Sassanid-era relief at Naqsh-e Rostam depicting Ahura Mazda presenting the diadem of sovereignty to Ardashir I. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Zarathushtra’s teachings are encapsulated in the Gathas, a collection of hymns within the Avesta. These hymns, attributed to Zarathushtra himself, express profound philosophical and theological insights, emphasizing the importance of ethical conduct, individual responsibility, and devotion to Ahura Mazda. Zarathushtra described himself as a prophet chosen by Ahura Mazda to guide humanity toward righteousness and to oppose the forces of evil embodied by Angra Mainyu (later Ahriman).

Depiction of Zoroaster in Clavis Artis, an alchemy manuscript published in Germany in the late 17th or early 18th century and pseudoepigraphically attributed to Zoroaster. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Core beliefs of Zoroastrianism

At the heart of Zoroastrian theology is a dualistic cosmology that frames the universe as a battleground between the forces of good, led by Ahura Mazda, and evil, represented by Angra Mainyu. This dualism is not absolute, as Zoroastrianism holds that Ahura Mazda’s ultimate victory is assured. Human beings, however, play a critical role in this cosmic struggle, as their thoughts, words, and deeds contribute to the triumph of good or evil.

Fravashi and the divine spark

Fravashi is the concept of a personal spirit of an individual, whether dead, living, or yet-unborn. The fravashi of an individual sends out the urvan (often translated as ‘soul’) into the material world to fight the battle of good versus evil. On the morning of the fourth day after death, the urvan returns to its fravashi, where its experiences in the material world are collected to assist the next generation in their fight between good and evil.

Faravahar, one of the primary symbols of Zoroastrianism, believed to be the depiction of a Fravashi or the Khvarenah. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Ethical monotheism and Ahura Mazda

Zarathushtra’s portrayal of Ahura Mazda as the supreme and singular deity was a departure from the polytheistic traditions of his time. Ahura Mazda is the creator of the universe, the source of all goodness, and the upholder of asha — the divine order of truth and justice. Worship of Ahura Mazda is central to Zoroastrian practice, and devotion is expressed through prayers, rituals, and ethical living.

![Kushan coinage of Huvishka with Ahuramazda on the reverse (Greek legend ωΡΟΜ, Orom[zdo]). 150–180 CE.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1e/Huvihska_with_Ahuramazda.jpg)

Kushan coinage of Huvishka with Ahuramazda on the reverse (Greek legend: ωΡΟΜ, Orom[zdo]). 150–180 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Human agency and free will

Zoroastrianism emphasizes the moral responsibility of individuals to choose between asha (truth, righteousness) and druj (falsehood, chaos). This concept of free will is revolutionary, as it empowers individuals to shape their destinies and contribute to the cosmic balance. The ultimate goal is to achieve Frashokereti, a final state of cosmic renewal in which evil is eradicated, and all creation is perfected.

Coinage of Kushan ruler Huvishka, with “Asha Vahishta” (ΑϷΑΕΙΧϷΟ, Ashaiexsho) on the reverse. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Fire and purity

Fire, a symbol of truth and divine presence, occupies a central place in Zoroastrian worship. Fire temples, where sacred flames are tended by priests, serve as places of communal prayer and ritual. The emphasis on fire reflects the broader Zoroastrian concern with purity, which extends to personal conduct, community life, and the environment.

Left: Atash Behram at the Fire Temple of Yazd in Iran. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0) – Right: The fire temple of Baku, c. 1860. Image extracted from A journey from London to Persepolis; including wanderings in Daghestan, Georgia, Armenia, by John Ussher. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Afterlife and eschatology

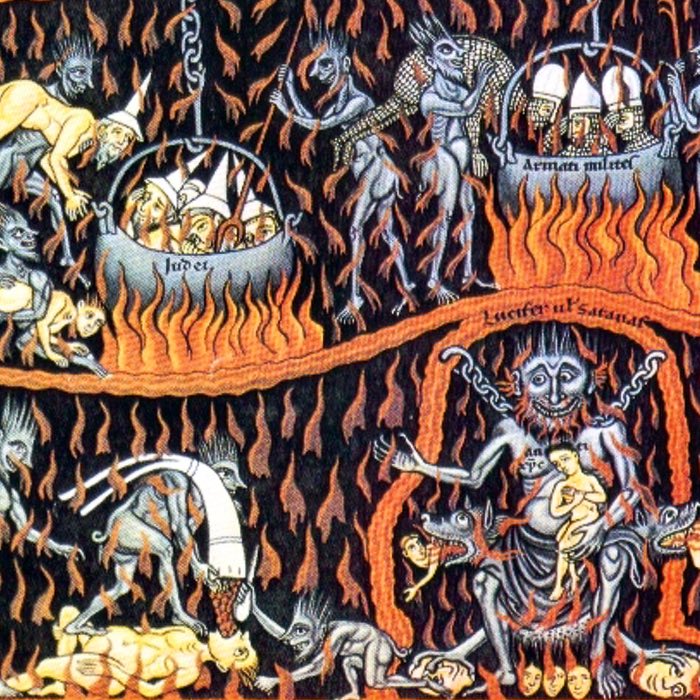

Zoroastrianism presents a detailed vision of the afterlife, in which the soul’s fate is determined by its adherence to asha. After death, the soul crosses the Chinvat Bridge, where it is judged based on its deeds. Those who live righteously join Ahura Mazda in a heavenly realm, while those who follow druj are condemned to a temporary existence of suffering. At the end of time, the resurrection of the dead and the final judgment will result in the ultimate defeat of evil and the restoration of all creation.

Line drawing of the eastern wall of the Sogdian sa-pao Wirkak’s sarcophagus in Hsi-an: Wirkak and his wife are on their way over the Chinvat Bridge to the Sogdian Paradise. Top right Wirkak and his wife can be seen feasting in Paradise, over them is the Sogdian God, Weshparkar, who welcomes the deceased. Upper left the sun god, Mithra, is hovering over the World together with some “apsaras”, which are a kind of angels and winged horses. A sinner seemed to be in free fall down towards the water. Under the bridge monsters are lurking for the sinners, who will be rejected by the guardians of the bridge. On the bridge the deceased are assumed to meet a fair young woman, who will be the personification of their life’s merits. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

THe Chinvat Bridge shares similarities with the concept of the Bridge of Sīrat in Islamic eschatology, where the souls of the deceased are judged before entering paradise or hell. Another analogy can be drawn with the Christian notion of the Last Judgment, where the dead are resurrected and judged based on their deeds. Jacob’s Ladder in Judaism and Christianity, which connects heaven and earth, also bears resemblance to the Zoroastrian concept of the Chinvat Bridge.

Core practices and cults

Zoroastrian practices revolve around maintaining the balance of asha through ritual, prayer, and ethical behavior. Daily prayers are recited facing a source of light, symbolizing the presence of Ahura Mazda. Ritual purity is meticulously observed, with ceremonies involving sacred elements such as fire, water, and earth.

The priestly class, known as magi, plays a crucial role in performing religious rituals, including those related to birth, marriage, and death. Funeral practices, such as the exposure of bodies in dakhmas (towers of silence), reflect the Zoroastrian concern with preserving the purity of natural elements.

Communal festivals, such as Nowruz (the Persian New Year), celebrate the renewal of creation and the triumph of light over darkness. These festivals are deeply intertwined with the agricultural cycles of ancient Iran, blending cosmic symbolism with practical observances.

An ancient relief at Persepolis for Nowruz (Persian New Year’s Day): Eternal combat between the bull, representing the Moon, and the lion, representing the Sun and spring. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Zoroastrianism’s revolutionary impact

Zarathushtra’s teachings were revolutionary for their emphasis on ethical monotheism, individual responsibility, and the moral dimension of the cosmos. These principles marked a departure from the ritualistic and fate-driven religions of the ancient world, offering instead a vision of personal agency and cosmic purpose.

Ahura Mazda (on the right, with high crown) presents Ardashir I (left) with the ring of kingship. (Naqsh-e Rostam, 3rd century CE). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

The religion’s eschatological focus, with its promise of a final triumph of good over evil, resonated deeply with later religious traditions. Its dualistic framework, ethical emphasis, and vision of a messianic figure (Saoshyant) influenced the development of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Concepts such as the resurrection of the dead, the final judgment, and the battle between good and evil bear striking parallels to Zoroastrian theology.

Zoroastrianism also shares affinities with Indian religions, particularly Vedic traditions. Both systems emphasize cosmic order (rita in Vedic, asha in Zoroastrian), the significance of fire in ritual, and a dualistic tension between creative and destructive forces. These shared elements reflect the common Indo-Iranian roots of both traditions.

Parallels with later religions

Judaism, Christianity, and Islam

Zoroastrianism’s influence on Judaism is evident in the post-exilic period, particularly in texts composed during and after the Babylonian captivity. The concepts of angels, demons, the Messiah, and an apocalyptic end of days are believed to have been shaped by Zoroastrian ideas.

Christianity adopted and expanded upon Zoroastrian eschatological themes, including the resurrection of the dead, the final judgment, and the ultimate defeat of evil. The figure of Satan in Christian theology bears similarities to Angra Mainyu, while the emphasis on moral choice echoes Zarathushtra’s teachings.

In Islam, parallels can be seen in the concepts of divine justice, judgment after death, and the dualistic struggle between good and evil. The ethical framework of Zoroastrianism, emphasizing the moral responsibility of individuals, finds resonance in Islamic teachings on accountability and righteousness.

Indian religions

Zoroastrianism’s shared Indo-Iranian heritage with Hinduism and other Vedic traditions is evident in its cosmology, ritual practices, and linguistic roots. The emphasis on fire rituals, the role of priests, and the dualistic struggle between order and chaos reflect a common cultural and religious ancestry.

Conclusion

Zarathushtra and Zoroastrianism represent a pivotal moment in the history of religion, introducing concepts and practices that shaped the spiritual landscape of the ancient world and beyond. Its emphasis on ethical monotheism, moral dualism, and individual responsibility set it apart as a revolutionary faith. The profound influence of Zoroastrianism on Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and Indian traditions underscores its legacy as a source of religious and philosophical inspiration.

References and further reading

- Boyce, M., Zoroastrians: their religious beliefs and practices, 1979, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415239035

- Stausberg, M., Zarathustra and Zoroastrianism: an introduction to the religion, 2008, Equinox Publishing Ltd, ISBN: 978-1845533205

- Gnoli, G., The idea of Iran: an essay on its origin, 1989, ISIAO, ISBN: 978-8863230697

- Modi, J. J., The religious ceremonies and customs of the Parsees, 2022, Legare Street Press, ISBN: 978-1017049671

comments