The philosophical roots of Yoga

Yoga, derived from the Sanskrit root yuj, meaning “to join” or “to unite”, is both a philosophical system and a set of physical, mental, and spiritual practices aimed at achieving self-realization and liberation (mokṣa). While modern popular notions of yoga emphasize its physical postures (āsanas), its origins lie in ancient Indian philosophical traditions, where it was primarily conceived as a disciplined path toward spiritual enlightenment. Over the centuries, yoga has evolved into various forms and schools, each emphasizing different aspects of practice and philosophy.

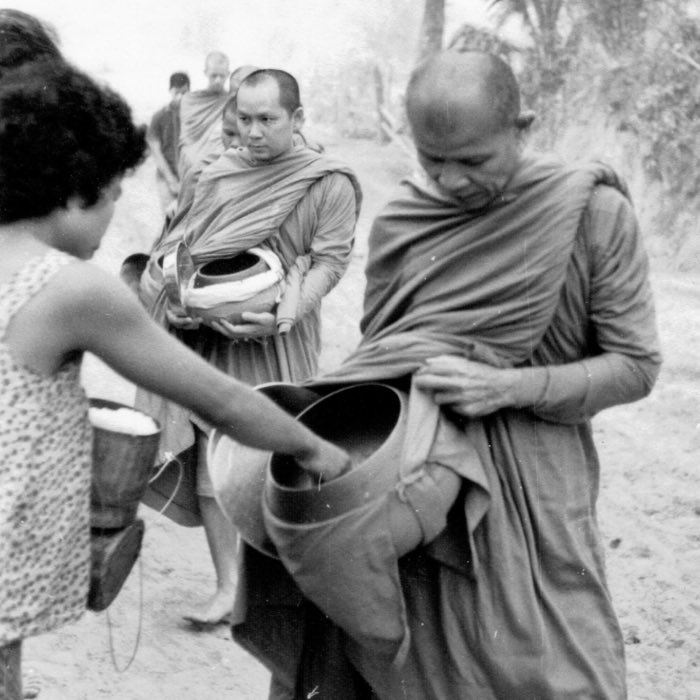

A yogi seated in a garden, North Indian or Deccani miniature painting, c.1620-40. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical origins of yoga

The origins of yoga can be traced back to the Indus Valley Civilization (circa 2500–1900 BCE), where archaeological evidence, such as seals depicting figures in meditative postures, suggests early forms of yogic practices. However, the first clear references to yoga appear in the Vedas, particularly in the Rigveda, where it is associated with the disciplined control of the mind and senses during rituals.

The earliest systematic discussion of yoga as a spiritual practice is found in the Upanishads (circa 800–300 BCE), especially the Katha Upanishad and the Śvetāśvatara Upanishad, where the concepts of meditation (dhyāna) and breath control (prāṇāyāma) are introduced. These texts emphasize the union of the individual self (ātman)) with the universal reality (brahman), a theme that would become central to later yogic traditions.

The Bhagavad Gītā (circa 400–200 BCE), a foundational text of Hindu philosophy, devotes an entire section to yoga, presenting it as a multifaceted discipline encompassing:

- Jñāna yoga: The path of knowledge.

- Bhakti yoga: The path of devotion.

- Karma yoga: The path of selfless action.

- Dhyāna yoga: The path of meditation.

The Gītā emphasizes that yoga is not merely a physical practice but a comprehensive way of life aimed at achieving spiritual liberation.

The classical system of Patañjali’s yoga

The most influential formulation of yoga as a systematic philosophical school is attributed to Patañjali, who composed the Yoga Sutras around the 2nd century BCE. The Yoga Sutras outline the aṣṭāṅga yoga (Eightfold Path), which serves as a guide to attaining self-discipline, inner peace, and ultimately, liberation:

- Yama: Ethical restraints (non-violence, truthfulness, non-stealing, celibacy, non-possessiveness).

- Niyama: Personal disciplines (cleanliness, contentment, austerity, self-study, surrender to the divine).

- Āsana: Physical postures that cultivate steadiness and comfort, preparing the body for prolonged meditation.

- Prāṇāyāma: Regulation of breath, which controls the life force (prāṇa).

- Pratyāhāra: Withdrawal of the senses from external objects, allowing the mind to turn inward.

- Dharāṇā: Concentration, focusing the mind on a single object.

- Dhyāna: Meditation, the continuous flow of thought toward the object of focus.

- Samādhi: Absorption or self-realization, where the practitioner transcends the ego and experiences unity with the universal consciousness.

Patañjali’s yoga is often referred to as Rāja yoga (“royal path”) because of its emphasis on mental discipline and meditation. It is fundamentally dualistic, positing a distinction between puruṣa (pure consciousness) and prakṛti (material nature). Liberation is achieved by realizing the separateness of puruṣa from prakṛti, thus freeing the self from the bonds of material existence.

Later developments and schools of yoga

Following Patañjali, several schools of yoga emerged, each interpreting and expanding upon his teachings in different ways. The most prominent among these are:

- Haṭha yoga: Haṭha yoga, first codified in texts such as the Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā (15th century CE), focuses on the physical aspects of yoga, particularly āsana and prāṇāyāma. Unlike Patañjali’s philosophical approach, haṭha yoga emphasizes bodily purification and the control of vital energy as prerequisites for higher spiritual practices. It introduced many of the physical postures now associated with modern yoga.

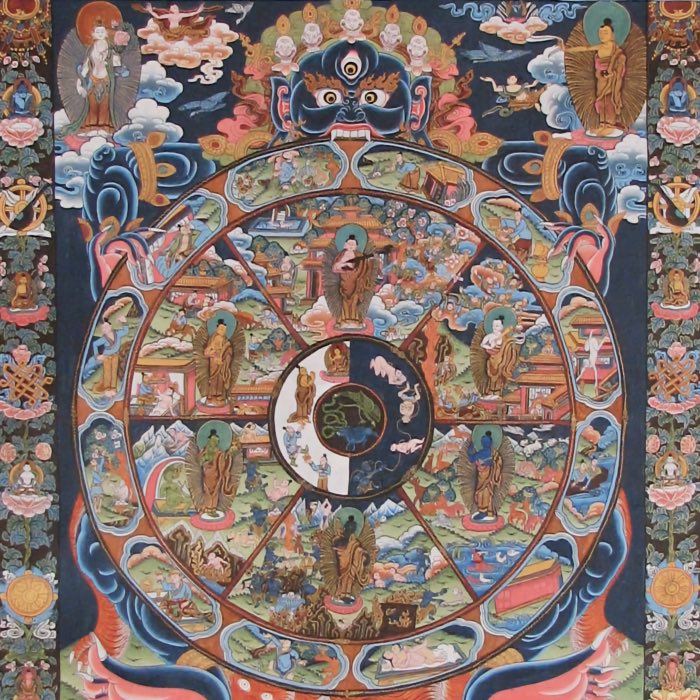

- Tantric yoga: Emerging around the 6th century CE, Tantric yoga integrates rituals, visualization, and the use of mantras and mudras (hand gestures) to awaken latent spiritual energies, particularly kuṇḍalinī energy believed to reside at the base of the spine.

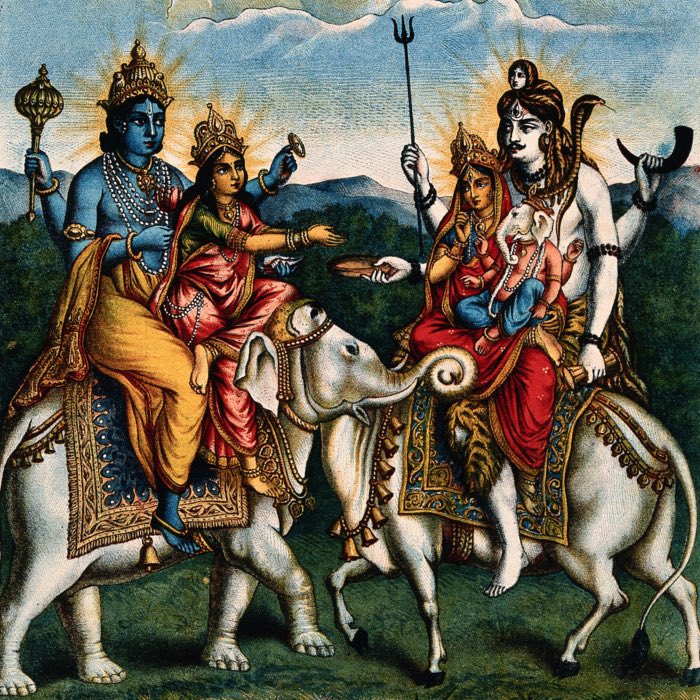

- Bhakti yoga: Bhakti yoga, or the path of devotion, became prominent with the rise of devotional movements in medieval India. It emphasizes loving devotion to a personal deity (e.g., Viṣṇu, Śiva, or the Goddess

- Jñāna yoga: The path of knowledge, closely associated with Advaita Vedānta, focuses on the realization of the non-duality (advaita) of ātman) and brahman through self-inquiry and contemplation.

- Karma yoga: Popularized by the Bhagavad Gītā and later by figures such as Swami Vivekananda, karma yoga advocates selfless action performed without attachment to the fruits of one’s labor.

Contemporary yoga: Global spread and adaptation

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, yoga began to attract global attention, largely due to the efforts of Indian teachers such as Swami Vivekananda, who introduced it to the West as a spiritual and philosophical practice. In the mid-20th century, teachers like B.K.S. Iyengar, Pattabhi Jois, and T. Krishnamacharya further popularized haṭha yoga by emphasizing physical postures and breath control.

Today, yoga has become a global phenomenon, practiced by millions as a means of physical fitness, stress relief, and spiritual growth. However, this modern interpretation often emphasizes āsana while neglecting the philosophical and meditative aspects of classical yoga.

Conclusion

Yoga, with its roots in ancient Indian philosophy, has evolved through various schools and traditions into a rich and multifaceted discipline. While modern yoga often emphasizes physical postures, its classical origins highlight a holistic approach aimed at achieving physical, mental, and spiritual well-being. By exploring its philosophical foundations and historical development, one can gain a deeper appreciation of yoga’s profound spiritual and philosophical dimensions, transcending its popular image as merely a form of physical exercise.

References and further reading

- Swami Satchidananda, The yoga sutras of Patañjali, 2012, Integral Yoga Publications, ISBN: 978-1938477072

- Mircea Eliade, Yoga: Immortality and freedom, 2009, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0691142036

- Mark Singleton, Yoga body: The origins of modern posture practice, 2010, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195395341

- David Gordon White, Sinister yogis, 2011, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 978-0226895147

- James Mallinson & Mark Singleton, Roots of yoga, 2017, Penguin Books, ISBN: 978-0241253045

comments