Yin-Yang: The dynamic balance of opposites in Daoist cosmology and philosophy

The concept of Yin-Yang (陰陽) is one of the most recognizable and foundational ideas in Daoist philosophy and traditional Chinese thought. It represents the dual, complementary forces that pervade the universe, illustrating how seemingly opposite or contrary elements are interconnected, interdependent, and constantly transforming into one another. Unlike rigid dualisms found in many other philosophical traditions, Yin-Yang embodies a fluid and dynamic interplay, emphasizing balance and harmony rather than conflict. In this post, we take a closer look at this concept beyond its popular esoteric and mystical connotations and explore its historical relevance for the East Asian cultural and intellectual landscape.

Yin-Yang, interpreted by DALL•E. It shows the common symbol of Yin and Yang in a modern artistic style, also called taijitu. The taijitu represents in Daoism the interplay of opposites and the cyclical nature of change.

Origins and metaphysical foundation of Yin-Yang

The earliest references to Yin-Yang can be traced back to ancient Chinese texts, such as the I Ching (Book of Changes), which predates Daoism but had a significant influence on its development. The I Ching presents the universe as a dynamic process governed by the interaction of Yin and Yang, symbolized by broken and unbroken lines representing these two complementary forces.

In Daoist thought, Yin and Yang are seen as manifestations of the Dao, the ultimate principle that underlies and unifies all existence. Rather than being static opposites, Yin and Yang are in constant flux, generating and balancing each other in a continuous process of transformation. This cyclical interaction is reflected in natural phenomena, such as the alternation of day and night, the changing of seasons, and the rhythms of life and death.

Yin is associated with qualities such as receptivity, darkness, softness, and passivity, while Yang represents activity, brightness, hardness, and assertiveness. Importantly, neither force is inherently superior or inferior; both are necessary for the functioning of the cosmos. The Daoist view of Yin-Yang emphasizes that harmony arises not from the dominance of one force over the other but from their balance and mutual complementarity.

Yin-Yang in Daoist cosmology

In Daoist cosmology, the interplay of Yin and Yang is fundamental to the creation and transformation of the universe. The Dao is said to give rise to the One (the undifferentiated whole), which then differentiates into Yin and Yang. The interaction of these forces generates the Ten Thousand Things (myriad phenomena), forming the world as we experience it.

The Dao De Jing describes this process in poetic terms, emphasizing the cyclical nature of existence and the interconnectedness of opposites. Laozi writes, “All things carry Yin yet embrace Yang. They blend their vital energies (Qi) to achieve harmony” (Dao De Jing, Chapter 42). This passage highlights the Daoist belief that all phenomena contain elements of both Yin and Yang and that their harmonious interaction is essential for the maintenance of balance in the world.

Furthermore, Yin-Yang is central to the Daoist understanding of change. Rather than seeing change as linear or chaotic, Daoism views it as the natural outcome of the interaction between Yin and Yang. When one force reaches its peak, it naturally transforms into the other. This is symbolized by the well-known Taijitu (Tai Chi symbol), which depicts a swirling circle of black and white with a dot of the opposite color in each half, representing the idea that Yin and Yang contain the seed of each other and are always in motion.

Ethical and practical implications of Yin-Yang

The concept of Yin-Yang has significant ethical and practical implications in Daoist philosophy. In contrast to moral systems that emphasize fixed rules or dichotomies of right and wrong, Daoism advocates for an adaptive, context-sensitive approach to ethics based on balance and harmony.

A Daoist ethical life involves recognizing and respecting the natural rhythms of Yin and Yang in oneself and the world. For example, Daoist texts often advise against excessive action (Yang) or excessive passivity (Yin), instead promoting a balanced approach that responds appropriately to changing circumstances. This balance is closely linked to the principles of wu wei (effortless action) and ziran (naturalness), which encourage individuals to act in accordance with the natural flow of the Dao rather than imposing their will on the world.

In personal conduct, Daoism encourages individuals to cultivate both Yin and Yang qualities, fostering flexibility, resilience, and openness. For instance, strength (Yang) is necessary for overcoming challenges, but softness (Yin) allows one to adapt and endure. By harmonizing these opposing forces within oneself, one can achieve a state of equilibrium and well-being.

Yin-Yang in daoist health practices

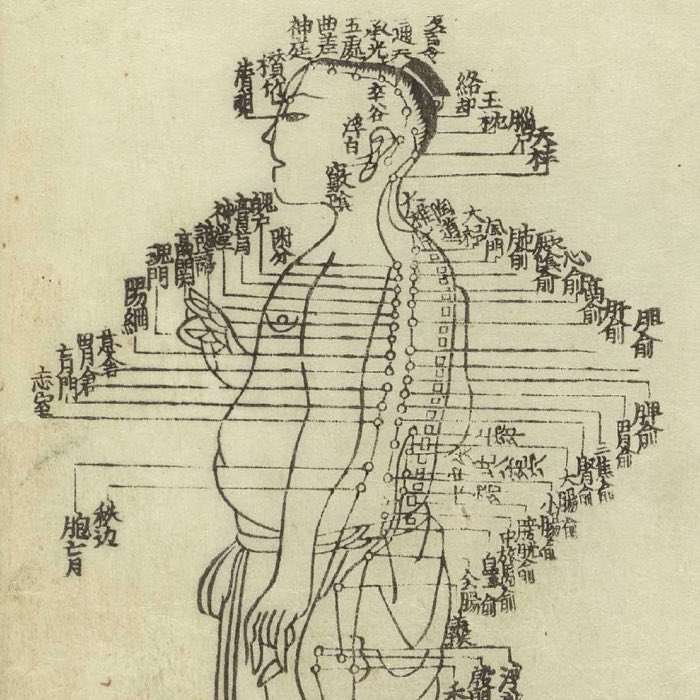

In Daoist medicine, which forms the basis of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), the concept of Yin-Yang is central to understanding health and disease. Health is seen as a state of dynamic balance between Yin and Yang energies within the body, while illness arises from an imbalance or blockage of these forces.

Practices such as acupuncture, herbal medicine, and Qigong aim to restore the balance of Yin and Yang by regulating the flow of Qi through the body’s meridians. For example, if a condition is characterized by excessive Yang (heat, activity), treatment may involve cooling herbs or techniques to restore Yin balance. Conversely, if a condition is marked by excessive Yin (cold, passivity), warming treatments may be applied.

The Daoist emphasis on balancing Yin and Yang in health extends to lifestyle practices, including diet, exercise, and sleep. Maintaining a balanced lifestyle in harmony with natural cycles—such as rising with the sun (Yang) and resting at night (Yin)—is considered essential for sustaining physical and mental well-being.

Yin-Yang in Daoist aesthetics and the arts

The influence of Yin-Yang extends beyond philosophy and health to Daoist aesthetics and the arts. In Daoist-influenced art forms, balance and harmony between opposites are key aesthetic principles. This can be seen in Chinese landscape painting, where light (Yang) and shadow (Yin), solid mountains (Yang) and flowing water (Yin), and open spaces and dense textures are carefully balanced to create a harmonious composition.

In poetry, Daoist-inspired poets such as Li Bai and Wang Wei often explore themes of balance and transformation, using imagery that reflects the interplay of Yin and Yang in nature. Their works evoke a sense of unity and harmony with the natural world, embodying the Daoist ideal of living in accordance with the Dao.

In martial arts, the principle of Yin-Yang is fundamental to styles such as Tai Chi, which emphasizes the balance of hard (Yang) and soft (Yin) movements. Practitioners learn to alternate between active and passive states, using their opponent’s force against them rather than meeting it with brute strength. This approach exemplifies the Daoist belief that true power arises from balance and adaptability.

Conclusion

The concept of Yin-Yang is a cornerstone of Daoist philosophy, offering a profound and holistic understanding of the nature of reality. By depicting opposites not as conflicting forces but as complementary aspects of a dynamic whole, Yin-Yang provides a framework for understanding change, harmony, and balance in the universe. Its influence extends beyond Daoism to various fields, including cosmology, ethics, health, and the arts, shaping the cultural and intellectual landscape of East Asia.

References

- Slingerland, Edward, Effortless action: Wu-wei as conceptual metaphor and spiritual ideal in early China, 2007, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195314878

- Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), I Ging: das Buch der Wandlungen, 2017, Nikol Verlag, ISBN: 9783868203950

- Laozi, Viktor Kalinke (Übersetzung), Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing, Bd. 1: Eine Wiedergabe seines Deutungsspektrums: Text, Übersetzung, Zeichenlexikon und Konkordanz, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015159

- Viktor Kalinke, Laozi, Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing, Bd. 2: Eine Erkundung seines Deutungsspektrums: Anmerkungen und Kommentare, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015180

- Viktor Kalinke, Nichtstun als Handlungsmaxime: Studien zu Laozi Daodejing, Bd. 3: Essay zur Rationalität des Mystischen, 2011, Leipziger Literaturverlag, ISBN: 9783866601154

- Laozi, Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), Tao te king - das Buch des alten Meisters vom Sinn und Leben, 2010, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783866474659

- Zhuangzi, Viktor Kalinke (Translator), Zhuangzi - Das Buch der daoistischen Weisheit, 2019, Reclam, ISBN: 9783150112397

- Lü Bu We (Autor), Richard Wilhelm (Herausgeber, Übersetzer), Das Weisheitsbuch der alten Chinesen - Frühling und Herbst des Lü Bu We, 2015, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783730602133

- Bokenkamp, Stephen R., Early Daoist scriptures, 1999, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520219311

- Kohn, Livia, Daoism and Chinese culture, 2005, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-1931483001

- Robinet, Isabelle, Daoism: Growth of a religion, 1997, Stanford University Press, ISBN: 978-0804728386

- Watson, Burton (trans.), The complete works of Zhuangzi, 2013, Columbia University Press, ISBN: 978-0231164740

- Martin Bödicker, Schrittweise das Dao Verwirklichen - Tianyinzi - Tägliche Übung - Riyong, 2015, Verlag n/a, ISBN: 9781512157475

- Martin Bödicker, Innere Übung - Neiye - Das Dao als Quelle - Yuandao, 2014, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, ISBN: 978-1503157071

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Michael S Diener (Herausgeber), Franz K Erhard (Herausgeber), Kurt Friedrichs (Herausgeber), Lexikon der östlichen Weisheitslehren - Buddhismus, Hinduismus, Daoismus, Zen, 1986, O.W. Barth, ISBN: 9783502674047

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Das Lexikon des Daoismus - Grundbegriffe und Lehrsysteme; Meister und Schulen; Literatur und Kunst; meditative Praktiken; Mystik und Geschichte der Weisheitslehre von ihren Anfängen bis heute, 1996, Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, ISBN: 9783442126644

comments