Wu Wei: The philosophical foundation of Daoist ethics and action

The concept of wu wei (無為), often translated as “non-action” or “effortless action”, occupies a central position in Daoist thought and has been a subject of profound philosophical reflection for centuries. Despite its literal meaning, wu wei does not imply passivity or inaction in the conventional sense. Instead, it denotes a mode of being and acting that is in perfect harmony with the natural flow of life, the Dao (道). Understanding wu wei requires an exploration of its metaphysical roots, its ethical implications, and its application in various domains of life, including governance, personal conduct, and the natural world.

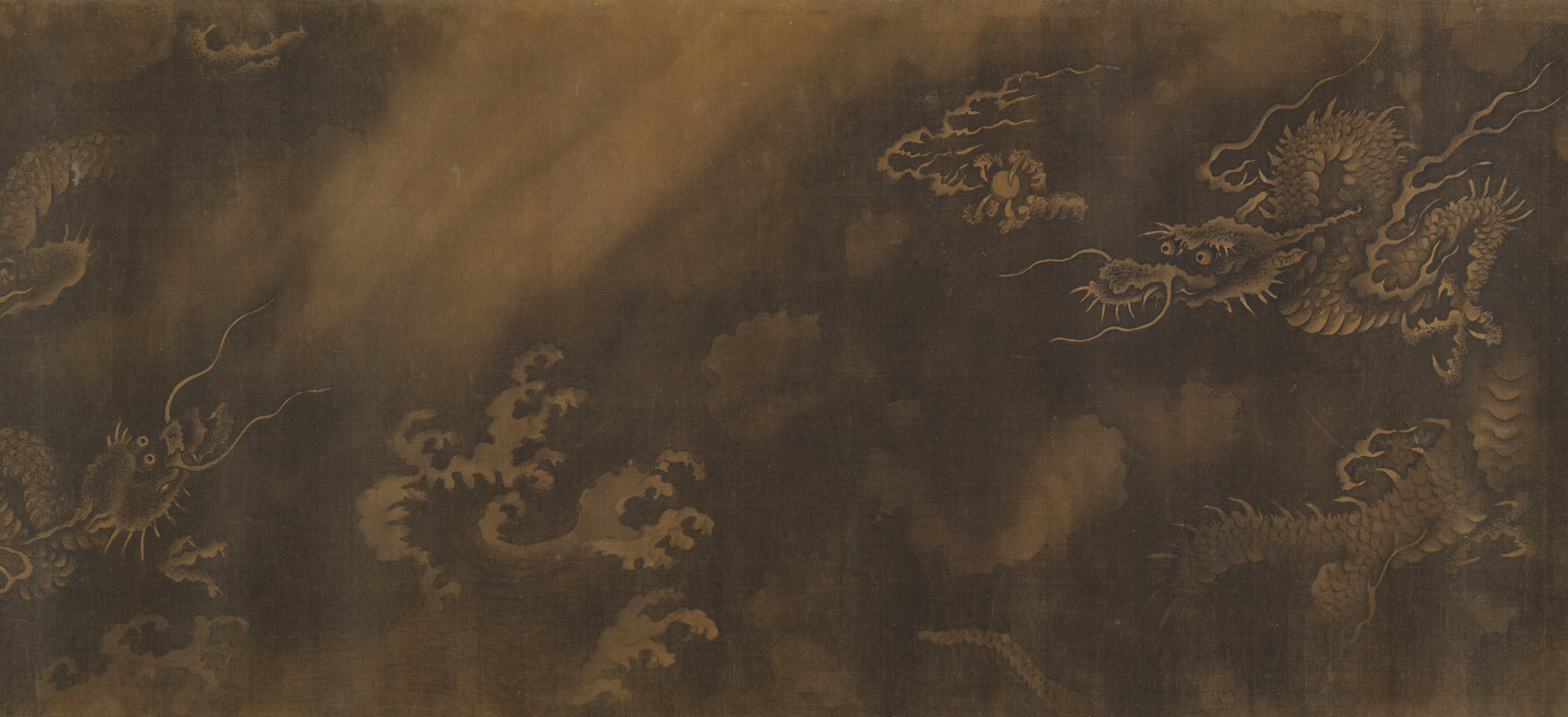

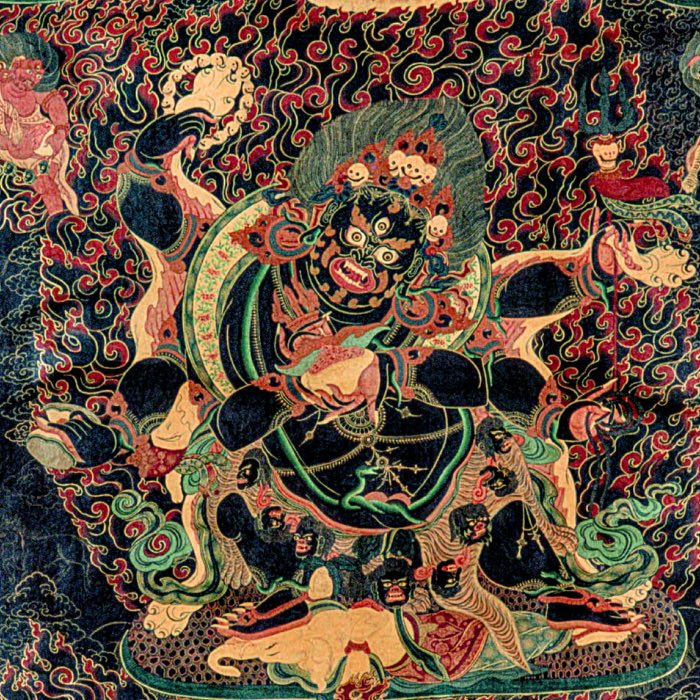

Cloudy Mountains, Zhang Yucai, late 13th–early 14th century, handscroll, ink and color on paper, China. Zhang Yucai, the thirty-eighth pope of the Zhengyi (“Orthodox Unity”) Daoist church, lived at Mount Longhu (Dragon Tiger Mountain) in Jiangxi Province. A favorite of the Yuan emperors, he received commendation from the Mongol court for inducing needed rain and for subduing a “tide monster” that had plagued the eastern seacoast. Dragons, as symbols of nature’s elemental forces, have been depicted in Chinese art from time immemorial. A special genre, dragon paintings were given powerful treatment by such Southern Song masters as Chen Rong (act. ca. 1235-62) and the Chán Buddhist painter Muqi (act. ca. 1240-75). In a fourteenth-century account, Chen’s working methods are described as follows: He “makes clouds by splashing ink, creates vapor by spraying water, and, while drunk, shouting loudly, takes off his cap, soaks it in ink, and smears and rubs with it, before finishing the painting with a brush.” On Chen Rong’s celebrated Nine Dragons handscroll dated 1244, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, there is a colophon dated 1331 by Zhang Yucai’s son Zhang Sicheng, the thirty-ninth Daoist pope (r. 1317–44). Beneficent Rain is closely related to Chen Rong’s Nine Dragons both in content and in style, and may have been directly inspired by the Boston scroll or others like it. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Arꜛ (public domain)

The metaphysical foundation of wu wei

The concept of wu wei is deeply rooted in Daoist metaphysics, particularly the nature of the Dao. In the Dao De Jing, attributed to Laozi, the Dao is described as the fundamental principle that underlies and pervades the cosmos. The Dao is not a creator in the sense of a conscious being but rather a force or process that operates without intent or effort. The Dao generates and sustains all things spontaneously, following its inherent nature.

In this context, wu wei can be seen as an extension of the Dao’s mode of operation. Just as the Dao acts without striving, so too should human beings align their actions with the natural order. Laozi emphasizes this in several passages of the Dao De Jing, such as, “The Dao never acts, yet nothing is left undone” (Dao De Jing, Chapter 37). This paradoxical statement suggests that true efficacy arises not from forceful intervention but from effortless alignment with the natural rhythms of life.

Wu wei and the critique of deliberate action

One of the key philosophical insights of wu wei is its critique of deliberate, contrived action (youwei, 有為), which often stems from human desire, ambition, and ego. Daoist thinkers argue that such actions disrupt the harmony of the Dao and lead to unnecessary conflict and suffering. According to Laozi, individuals who act with too much intent and force create imbalance, whereas those who practice wu wei maintain harmony by following the path of least resistance.

Zhuangzi, another foundational figure in Daoism, elaborates on this critique by illustrating the futility of imposing rigid structures on the world. In the Zhuangzi, he presents numerous parables that highlight the superiority of spontaneous, intuitive action over calculated effort. For example, in the story of the butcher who carves oxen with effortless precision, Zhuangzi illustrates how mastery arises not from force but from attunement to the natural patterns of the ox’s body. The butcher’s skill embodies wu wei, as his actions flow seamlessly from his deep understanding of the Dao inherent in his craft.

Ethical dimensions of wu wei

Ethically, wu wei promotes a way of life characterized by humility, simplicity, and receptivity. Rather than striving to dominate or control the world, Daoism advocates for living in harmony with it. This contrasts sharply with the Confucian emphasis on active moral cultivation and social responsibility. While Confucianism stresses deliberate effort in achieving moral virtue and societal order, Daoism sees virtue as something that arises naturally when one aligns with the Dao.

In Daoist ethics, the ideal individual is the sage (shengren, 聖人), who embodies wu wei by acting spontaneously and effortlessly in accordance with the Dao. The sage does not impose their will on the world but responds to situations as they arise, maintaining balance and harmony. This approach to ethics is not prescriptive but adaptive, emphasizing flexibility and openness rather than rigid adherence to moral rules.

Furthermore, wu wei encourages a deep respect for nature and a recognition of humanity’s place within the broader cosmic order. By following wu wei, individuals cultivate an attitude of humility and gratitude toward the natural world, avoiding actions that disrupt its balance. This ecological ethic has significant contemporary relevance, particularly in discussions about environmental sustainability and conservation.

Wu wei in governance and leadership

One of the most striking applications of wu wei in Daoist philosophy is in the realm of governance. Laozi devotes considerable attention to this topic in the Dao De Jing, proposing a model of leadership that contrasts sharply with the authoritarian and interventionist tendencies of his time. According to Laozi, the ideal ruler governs through wu wei, allowing the people to live naturally and harmoniously without unnecessary interference.

In Chapter 57 of the Dao De Jing, Laozi writes, “I take no action, and the people are transformed of themselves. I prefer stillness, and the people right themselves. I do not interfere, and the people prosper.” This vision of governance reflects the Daoist belief that excessive control and regulation lead to disorder, whereas non-coercive leadership fosters peace and prosperity. The ruler who practices wu wei acts as a steward rather than a master, guiding subtly and unobtrusively.

Historically, Daoist ideas of wu wei influenced certain periods of Chinese governance, particularly during the early Han dynasty, when rulers adopted a policy of minimal intervention known as huang-lao (黄老), named after Huangdi (the Yellow Emperor) and Laozi. This policy emphasized light taxation, minimal bureaucracy, and a laissez-faire approach to economic and social affairs. Although later dynasties moved away from these principles, the Daoist ideal of wu wei continued to inform debates on governance and leadership throughout Chinese history.

Wu wei in the natural world and the arts

In addition to its ethical and political dimensions, wu wei has profound implications for understanding the natural world and human creativity. Daoism views nature as the ultimate exemplar of wu wei, operating effortlessly and spontaneously in accordance with the Dao. The cycles of seasons, the flow of rivers, and the growth of plants all occur without force or intent, embodying the principle of wu wei.

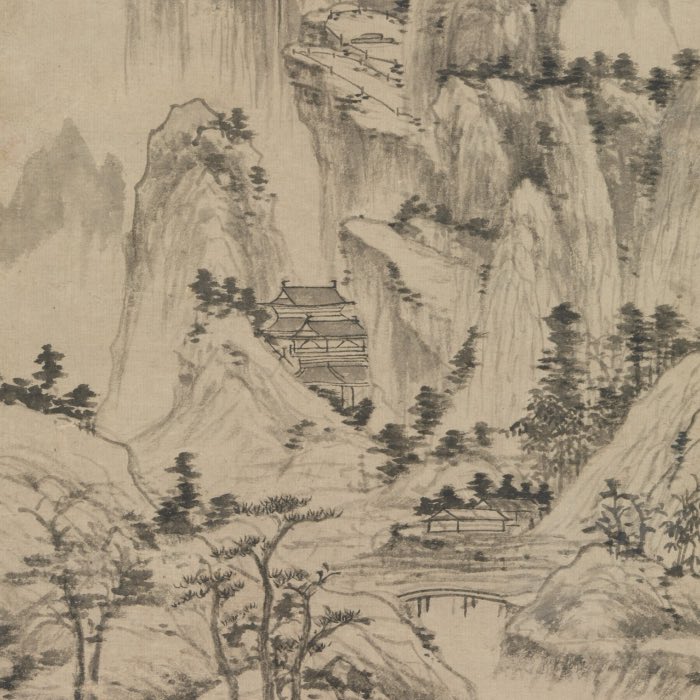

This Daoist reverence for natural processes extends to the arts, where wu wei is reflected in aesthetic ideals such as spontaneity, simplicity, and naturalness (ziran, 自然). In Chinese landscape painting, for example, artists sought to capture the essence of nature through intuitive and unforced brushstrokes, allowing the Dao to express itself through their work. Similarly, in calligraphy and poetry, the practice of wu wei involves cultivating a state of flow in which creativity arises effortlessly from a deep connection with the Dao.

In martial arts, wu wei manifests as the principle of yielding to an opponent’s force rather than resisting it. Daoist-inspired martial arts, such as Tai Chi, emphasize softness, flexibility, and responsiveness, embodying the idea that true strength lies in adaptability and non-resistance.

Conclusion

The concept of wu wei offers a profound and holistic vision of action, ethics, and leadership. Far from promoting passivity, wu wei represents a mode of engagement with the world that is fluid, adaptive, and in harmony with the natural order. In the Daoist philosophical system, wu wei serves as the guiding principle for living in accordance with the Dao, allowing individuals to act without force or contrivance, thus preserving balance and minimizing conflict.

References

- Slingerland, Edward, Effortless action: Wu-wei as conceptual metaphor and spiritual ideal in early China, 2007, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195314878

- Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), I Ging: das Buch der Wandlungen, 2017, Nikol Verlag, ISBN: 9783868203950

- Laozi, Viktor Kalinke (Übersetzung), Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing, Bd. 1: Eine Wiedergabe seines Deutungsspektrums: Text, Übersetzung, Zeichenlexikon und Konkordanz, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015159

- Viktor Kalinke, Laozi, Studien zu Laozi, Daodejing, Bd. 2: Eine Erkundung seines Deutungsspektrums: Anmerkungen und Kommentare, 2000, Leipziger Literaturverlag, 2. Auflage, ISBN: 9783934015180

- Viktor Kalinke, Nichtstun als Handlungsmaxime: Studien zu Laozi Daodejing, Bd. 3: Essay zur Rationalität des Mystischen, 2011, Leipziger Literaturverlag, ISBN: 9783866601154

- Laozi, Richard Wilhelm (Übersetzer), Tao te king - das Buch des alten Meisters vom Sinn und Leben, 2010, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783866474659

- Zhuangzi, Viktor Kalinke (Translator), Zhuangzi - Das Buch der daoistischen Weisheit, 2019, Reclam, ISBN: 9783150112397

- Lü Bu We (Autor), Richard Wilhelm (Herausgeber, Übersetzer), Das Weisheitsbuch der alten Chinesen - Frühling und Herbst des Lü Bu We, 2015, Anaconda, ISBN: 9783730602133

- Bokenkamp, Stephen R., Early Daoist scriptures, 1999, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520219311

- Kohn, Livia, Daoism and Chinese culture, 2005, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 978-1931483001

- Robinet, Isabelle, Daoism: Growth of a religion, 1997, Stanford University Press, ISBN: 978-0804728386

- Watson, Burton (trans.), The complete works of Zhuangzi, 2013, Columbia University Press, ISBN: 978-0231164740

- Martin Bödicker, Schrittweise das Dao Verwirklichen - Tianyinzi - Tägliche Übung - Riyong, 2015, Verlag n/a, ISBN: 9781512157475

- Martin Bödicker, Innere Übung - Neiye - Das Dao als Quelle - Yuandao, 2014, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, ISBN: 978-1503157071

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Michael S Diener (Herausgeber), Franz K Erhard (Herausgeber), Kurt Friedrichs (Herausgeber), Lexikon der östlichen Weisheitslehren - Buddhismus, Hinduismus, Daoismus, Zen, 1986, O.W. Barth, ISBN: 9783502674047

- Ingrid Fischer-Schreiber, Das Lexikon des Daoismus - Grundbegriffe und Lehrsysteme; Meister und Schulen; Literatur und Kunst; meditative Praktiken; Mystik und Geschichte der Weisheitslehre von ihren Anfängen bis heute, 1996, Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, ISBN: 9783442126644

comments