Vedanta: Philosophy of the Upanishads

Vedanta, meaning “end of the Vedas” in Sanskrit, refers to a collection of philosophical traditions that explore the nature of reality, the self (ātman)), and the ultimate principle (brahman). Rooted in the Upanishads, which are the concluding portions of the Vedic literature, Vedanta evolved into one of the most influential schools of Indian philosophy. While initially a metaphysical inquiry into the unity of the individual and the cosmos, Vedanta developed into several distinct schools, each offering unique interpretations of the core texts and concepts. In this post, we briefly take a look at the most important aspects of Vedanta, its historical origins, core philosophical concepts, principal schools, and its role in Hindu religious practice.

Shankaracharya, a renowned exponent of Advaita Vedanta, depicted in a painting form 1904. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Historical origins and foundational texts

The philosophical foundation of Vedanta lies in the Upanishads (circa 800–300 BCE), which marked a significant shift from the ritualistic focus of the earlier Vedas to a more introspective and philosophical exploration of existence. Among the principal Upanishads are:

- Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upanishad: One of the oldest and most comprehensive Upanishads, offering profound discussions on the nature of ātman) and brahman.

- Chāndogya Upanishad: Known for its teachings on the unity of the self and the cosmos, particularly the famous statement “tat tvam asi” (“You are that”).

- Māṇḍūkya Upanishad: A short but highly influential text that presents the four states of consciousness—waking, dreaming, deep sleep, and the transcendent state (turīya).

- Taittirīya Upanishad: Offers a layered view of the self, from the physical body to the ultimate self.

In addition to the Upanishads, two other texts are considered foundational to Vedanta:

- Brahma Sutras (Vedānta Sutras): Composed by Bādarāyaṇa around the 2nd century BCE, the Brahma Sutras systematically interpret the Upanishads, establishing a coherent framework for Vedantic philosophy.

- Bhagavad Gītā: As part of the Mahābhārata, the Gītā synthesizes Vedic and Upanishadic thought, presenting a practical guide to living a life of devotion (bhakti), knowledge (jñāna), and selfless action (karma).

Core philosophical concepts

Vedanta revolves around several core philosophical concepts that define its inquiry into reality and liberation:

- Brahman: The ultimate, formless, infinite, and eternal reality that is the source of all existence. Brahman is beyond sensory perception and conceptual thought, yet it pervades everything.

- Ātman): The individual self or soul, which Vedanta posits as ultimately identical to Brahman. The realization of this identity is central to achieving liberation (mokṣa).

- Māyā: Often translated as “illusion”, māyā refers to the apparent reality of the world, which veils the true nature of Brahman. The experience of duality and separation is attributed to māyā.

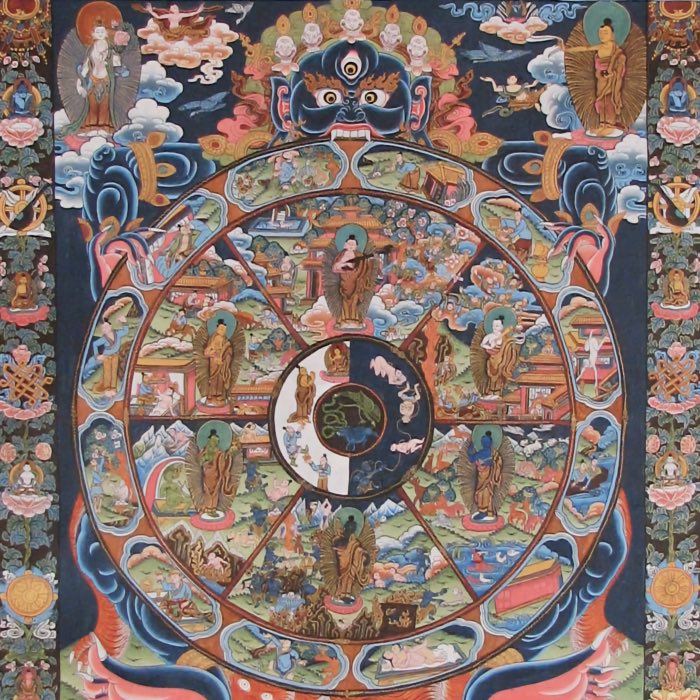

- Karma and samsāra: Vedanta, like other Indian philosophical systems, acknowledges the law of karma (cause and effect) and the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsāra). Liberation involves breaking free from this cycle.

- Mokṣa: The ultimate goal of Vedanta is mokṣa, or liberation, which is achieved through self-realization—the direct experience of the unity of ātman) and brahman.

Principal schools of Vedanta

Over time, Vedanta gave rise to several distinct schools, each interpreting the Upanishads and other foundational texts in different ways. The three most prominent schools are:

Advaita Vedanta (Non-dualism)

Founded by Ādi Śaṅkara (8th century CE), Advaita Vedanta is the most well-known and philosophically rigorous school of Vedanta. It teaches that Brahman alone is real, and the world is an illusory appearance (māyā). According to Advaita, the individual self (ātman)) is not different from Brahman, and liberation is achieved by realizing this non-duality (advaita).

Key tenets of Advaita include:

- Brahman is the only reality: Everything else, including the world and individual selves, is ultimately unreal (mithyā).

- Jñāna (knowledge) as the path to liberation: Self-realization through direct knowledge of non-duality leads to mokṣa.

- Sublation of duality: The perception of duality and multiplicity is due to ignorance (avidyā), which is dispelled through philosophical inquiry and meditation.

Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedanta (Qualified non-dualism)

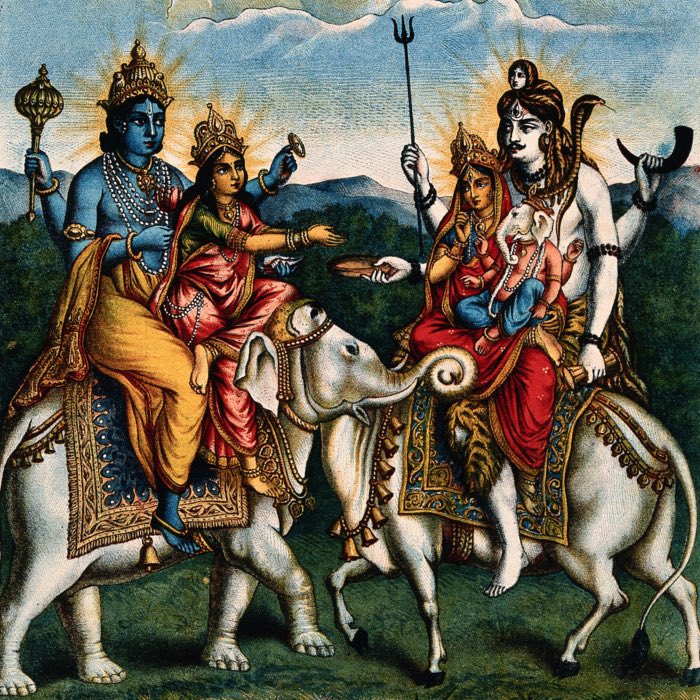

Viśiṣṭādvaita was developed by Rāmānuja (11th century CE) as a response to Advaita Vedanta. While accepting the non-duality of Brahman, Rāmānuja argued that Brahman is not an abstract, formless entity but is characterized by qualities (viśeṣa) and is identified with the personal god Viṣṇu.

Key aspects of Viśiṣṭādvaita include:

- Brahman with attributes: Brahman possesses both essential and distinguishing attributes and manifests as the personal deity Viṣṇu.

- Unity with distinction: The world and individual selves are real and distinct, but they exist as modes of Brahman.

- Bhakti (devotion) as the path to liberation: Rāmānuja emphasized devotion to Viṣṇu as the primary means to achieve liberation.

Dvaita Vedanta (Dualism)

Dvaita Vedanta, founded by Madhva (13th century CE), asserts a strict dualism between ātman) and brahman. Unlike Advaita and Viśiṣṭādvaita, Madhva posited that the individual soul and Brahman are eternally distinct.

Key principles of Dvaita include:

- Brahman as completely distinct from the self: Brahman, identified with Viṣṇu, is the supreme being, and individual souls are eternally dependent on him.

- Reality of the world: Madhva rejected the notion of māyā as illusion, maintaining that the world is real.

- Devotion and grace: Liberation is achieved through devotion to Viṣṇu and reliance on his grace.

Other schools and later developments

In addition to the three principal schools, several other Vedantic traditions emerged, including:

- Bhedābheda Vedanta: A school that posits both difference and non-difference between ātman) and brahman.

- Śuddhādvaita Vedanta: Founded by Vallabha (15th century CE), this school emphasizes pure non-dualism and devotion to Kṛṣṇa.

- Dvaitādvaita Vedanta: Propounded by Nimbārka (12th century CE), this school holds that the self is both distinct from and identical to Brahman.

Vedanta in practice

Although Vedanta is primarily a philosophical tradition, its teachings have had a profound impact on Hindu religious practices. The devotional movements associated with Viṣṇu, Śiva, and the Goddess draw heavily on Vedantic concepts. Meditation, self-inquiry, and ethical living, inspired by Vedantic philosophy, remain integral to many spiritual paths in Hinduism.

Conclusion

Vedanta represents a profound and diverse tradition of philosophical inquiry into the nature of reality, consciousness, and liberation. Building on the metaphysical foundations laid by the Upanishads, Vedanta synthesizes earlier Indian philosophical ideas, such as the Upanishadic concepts of brahman and ātman) and the ethical framework of dharma. While its various schools — Advaita, Viśiṣṭādvaita, and Dvaita — differ in their interpretations, they converge on the ultimate goal of attaining liberation (mokṣa) through knowledge, devotion, or self-discipline. In this way, Vedanta not only advanced earlier philosophical discourses but also provided a cohesive framework that continues to influence Indian religious practice and intellectual thought.

References and further reading

- S. Radhakrishnan, Indian philosophy, vol. 2, 2017, Forgotten Books, ISBN: 978-0282624736

- Chandradhar Sharma, The Advaita tradition in Indian philosophy, 2024, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-9357600705

- Hajime Nakamura, A history of early Vedanta philosophy, 1990, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120806511

comments