Śramaṇa: The ascetic movement in ancient India, that challenged Vedic orthodoxy

The Śramaṇa tradition represents a significant spiritual and philosophical movement in ancient India that emerged around the 6th century BCE. The term śramaṇa is derived from the Sanskrit root “śram” (to exert or toil) and refers to ascetics who renounced worldly life in pursuit of spiritual liberation (mokṣa). Unlike the Vedic tradition, which emphasized ritual sacrifices and the authority of the Brahmin priesthood, the śramaṇa movement was characterized by its rejection of Vedic orthodoxy, ritualism, and the caste system. This movement gave rise to several heterodox philosophies, including Jainism, Buddhism, and Ājīvika, each offering alternative paths to liberation.

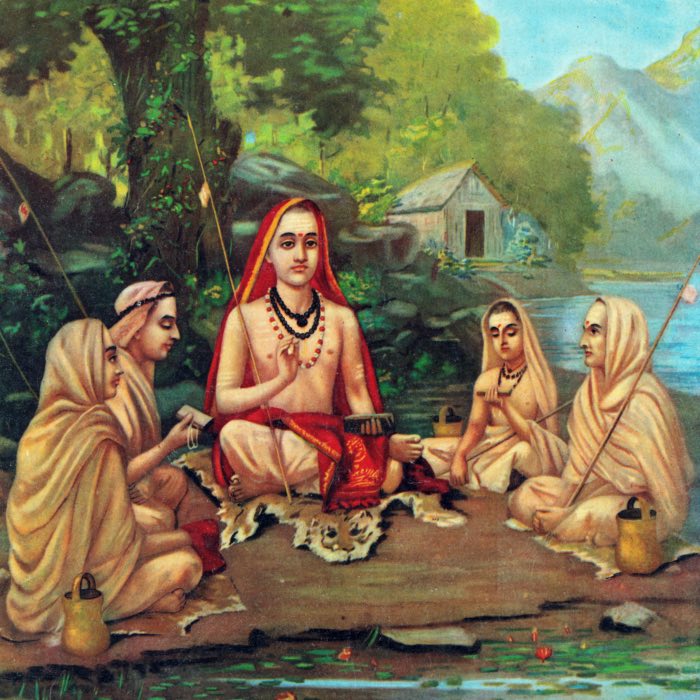

Thai forest tradition monks led by Ajahn Maha Bua out for the morning alms round. Buddhist monks follow the Vinaya, a set of monastic rules that guide their conduct and lifestyle. One of these rules is to rely on alms for their daily sustenance. This routes back to the early Buddhist ties to the śramaṇa tradition of that time. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

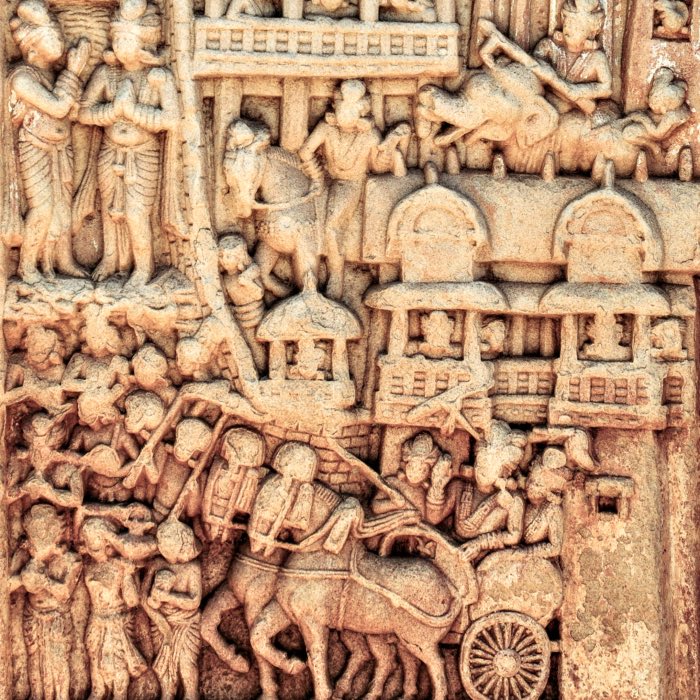

Historical context and origins

The Śramaṇa movement emerged during a period of significant social and intellectual transformation in ancient India. Urbanization, the rise of kingdoms, and increased trade led to changes in the social structure and the questioning of traditional values. The Vedic tradition, centered on rituals and sacrifices performed by the Brahmin class, began to face criticism for its exclusivity and inability to address existential questions about suffering and liberation.

The śramaṇas sought answers to these questions through personal effort, austerity, and meditation, rather than through rituals and scriptural study. They rejected the authority of the Vedas and proposed that liberation could be achieved by individuals through their own spiritual practices.

Key teachings of the śramaṇa movement

While the śramaṇa schools differed in their philosophical doctrines, they shared certain key teachings and practices:

- Rejection of Vedic authority

- The śramaṇa traditions rejected the notion that the Vedas were divinely revealed or infallible. They criticized the ritualism and caste-based hierarchy of Vedic society.

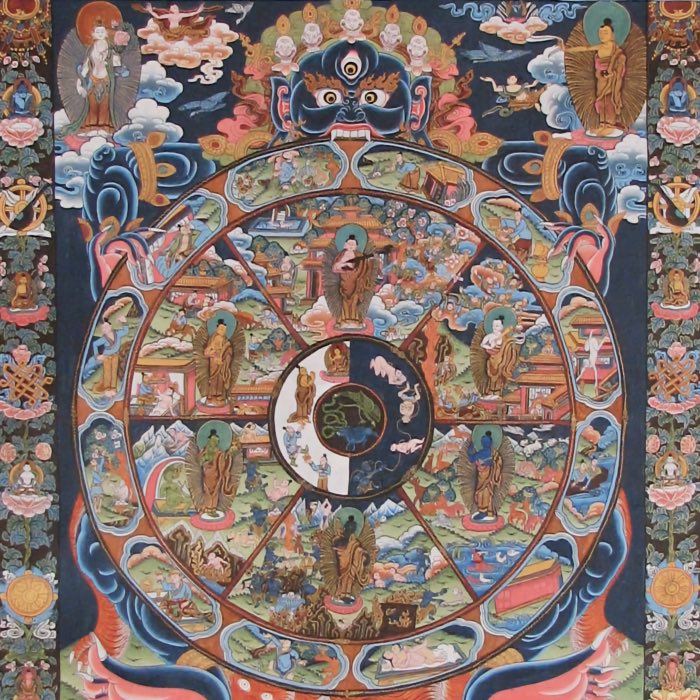

- Karma and rebirth

- All śramaṇa schools accepted the concepts of karma (moral causality) and samsāra (cycle of rebirth), but they offered different interpretations of how these worked and how liberation could be attained.

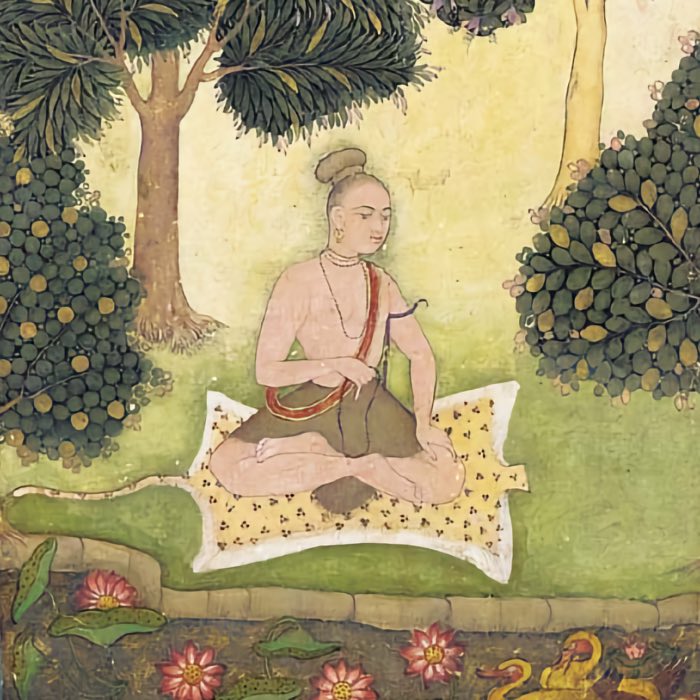

- Austerity and asceticism (tapas)**

- Ascetic practices, including fasting, celibacy, and renunciation of worldly possessions, were central to the śramaṇa way of life. These practices were seen as a means to purify the self and overcome desires.

- Meditation and self-discipline

- Meditation and mental discipline were emphasized as essential tools for attaining liberation. Different schools developed their own meditative techniques and philosophical frameworks for understanding the mind.

- Path to liberation

- Unlike the Vedic tradition, which emphasized performing one’s social duties (dharma) to attain a better rebirth, the śramaṇa traditions focused on breaking free from the cycle of samsāra altogether.

Major śramaṇa schools

The Śramaṇa movement was diverse, giving rise to several important philosophical schools. The three most prominent schools are:

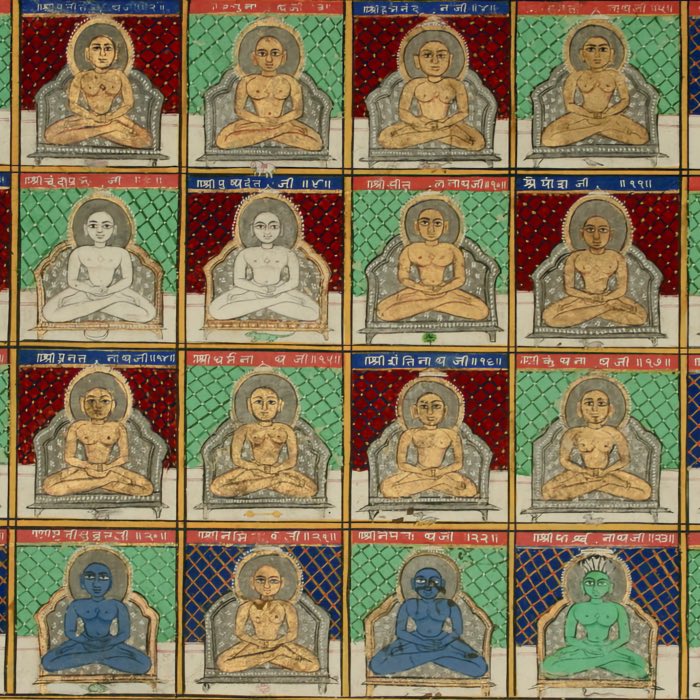

Jainism

Founded by Mahāvīra (circa 599–527 BCE), Jainism is one of the oldest surviving śramaṇa traditions. Key teachings of Jainism include:

- Ahiṃsā (non-violence): The central tenet of Jainism, ahiṃsā, advocates absolute non-violence toward all living beings. Jain ascetics practice extreme forms of non-violence, including careful walking and wearing masks to avoid harming insects.

- Anekāntavāda (multiplicity of viewpoints): Jain philosophy emphasizes the relativity of truth, asserting that reality can be perceived from multiple perspectives.

- Karma as a material substance: In Jainism, karma is viewed as a form of subtle matter that binds to the soul, causing rebirth. Liberation involves purging all karma through ascetic practices and ethical conduct.

Buddhism

Founded by Gautama Buddha (circa 563–483 BCE), Buddhism developed as a major śramaṇa tradition that spread across Asia. Key teachings of Buddhism include:

- Four Noble Truths: The Buddha’s core teaching revolves around understanding suffering (duḥkha), its cause (tṛṣṇā or craving), its cessation (nirvāṇa), and the path to its cessation (Ārya Aṣṭāṅga Mārga or the Eightfold Path).

- Anatta (non-self): Unlike other śramaṇa schools, Buddhism denies the existence of a permanent self (ātman)), emphasizing the impermanent and interdependent nature of all phenomena.

- Middle Way: The Buddha advocated a balanced path between extreme asceticism and indulgence, known as the Middle Way.

Ājīvika

The Ājīvika school, founded by Makkhali Gosāla, was another influential śramaṇa tradition, though it eventually declined. Key features of Ājīvika philosophy include:

- Determinism: The Ājīvikas believed in strict determinism, holding that everything in life is predetermined by fate (niyati), and individual effort plays no role in altering one’s destiny.

- Karma and rebirth: Although they accepted the concepts of karma and samsāra, the Ājīvikas argued that liberation was achieved through the natural unfolding of cosmic law, rather than through personal effort.

- Ascetic practices: Like other śramaṇa schools, the Ājīvikas practiced rigorous asceticism, including nudity and extreme fasting.

Influence on Hinduism

The Śramaṇa movement had a profound impact on the development of Hindu philosophy and spirituality. While initially seen as a challenge to Vedic orthodoxy, the success of the śramaṇa schools prompted Hindu thinkers to reinterpret and integrate many of their ideas. Key influences include:

- Karma and rebirth: The concepts of karma and samsāra, initially central to the śramaṇa traditions, were incorporated into Hindu thought and became integral to Hindu cosmology.

- Asceticism: The renunciant ideal, embodied by the śramaṇa ascetics, was adopted by Hindu traditions, leading to the development of monastic orders (sannyāsa) and ascetic practices.

- Philosophical inquiry: The philosophical debates between śramaṇa schools and Vedic thinkers led to the emergence of Vedanta, Sāṃkhya, and Yoga as systematic schools of thought, many of which addressed the challenges posed by Jainism and Buddhism.

Conclusion

The Śramaṇa movement represents a pivotal chapter in the spiritual history of India, offering alternative paths to liberation through asceticism, ethical conduct, and philosophical inquiry. Its rejection of Vedic orthodoxy and emphasis on personal effort and self-discipline laid the groundwork for Jainism, Buddhism, and other ascetic traditions. By challenging established norms and exploring profound questions about existence, the śramaṇa traditions indeed left an indelible mark on the philosophical landscape of ancient India.

References and further reading

- Bronkhorst, The two traditions of meditation in ancient India, 2000, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120816435

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Indian philosophy, vol. 1, 2018, FB&C LTD, ISBN: 978-0331594577

- M. Hiriyanna, Essentials of Indian philosophy, 1995, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120813045

- Chandradhar Sharma, A critical survey of Indian philosophy, 2000, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120803657

- Paul Dundas, The Jains, 2002, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415266062

comments