The Silk Road: A network of ancient trade, cultural exchange, and global transformation

The Silk Road, a vast network of trade routes connecting East Asia to the Mediterranean, played a critical role in shaping the economic, cultural, and political history of the ancient world. Spanning over 6,000 kilometers and linking regions as diverse as China, Central Asia, Persia, India, Mesopotamia, and the Roman Empire, the Silk Road facilitated an unprecedented exchange of goods, ideas, technologies, and religious beliefs. Its significance lies not only in the commodities that were traded but also in the profound cultural interactions that transformed the civilizations it connected.

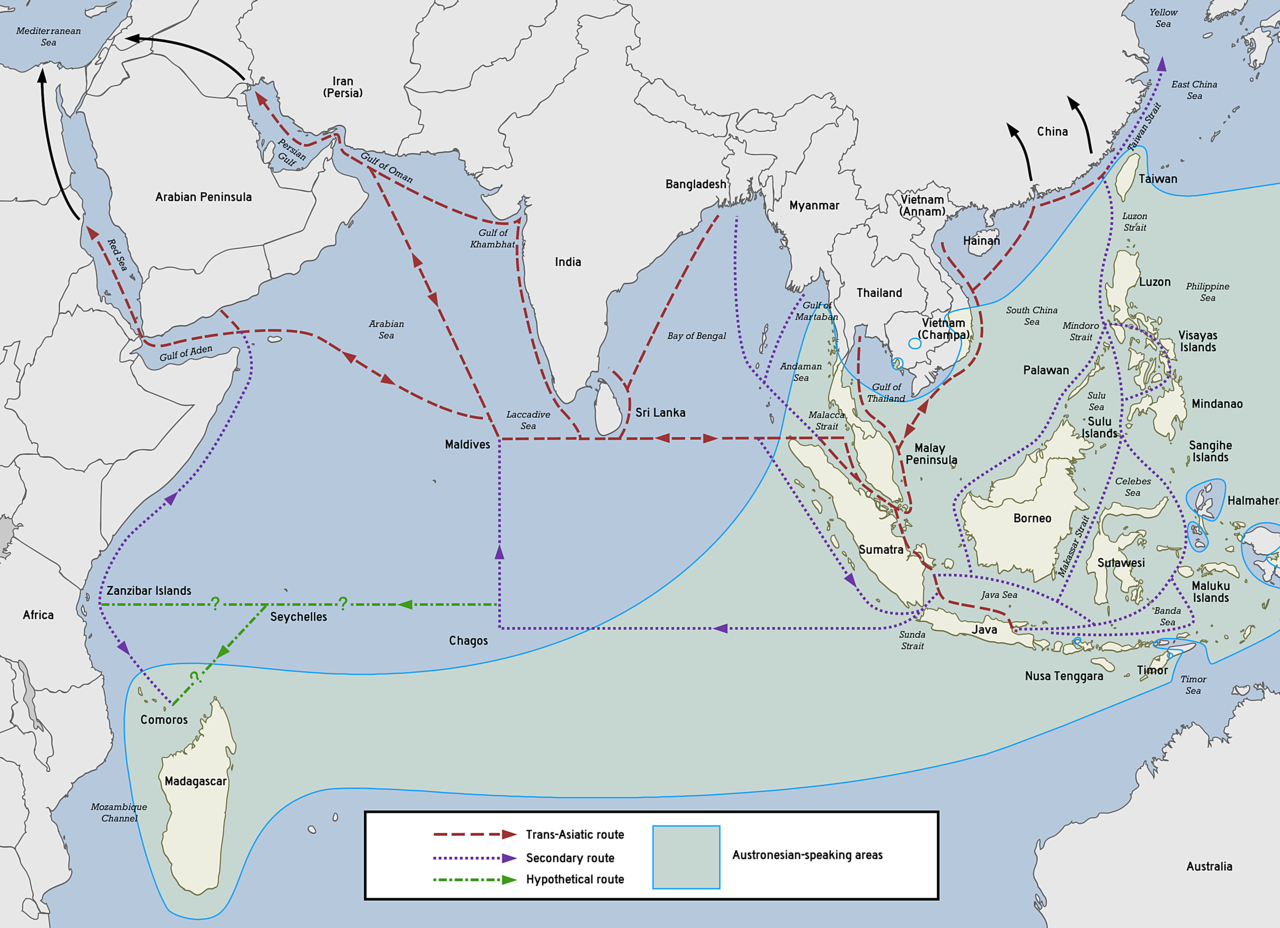

Map of Eurasia and Africa showing trade networks, c. 870 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Alongside other ancient trade routes, such as the Lapis Lazuli Route and the Amber Road, the Silk Road provides compelling evidence of a dynamic flow of commerce and ideas in ancient times. Driven by the pursuit of wealth and sustained by the efforts of countless traders, merchants, and explorers, these routes inadvertently created a vast network that connected the known world far more extensively than might initially be imagined. While the speed and scale of this exchange were vastly different from those of modern global trade, the underlying principles of cultural and economic interaction remain remarkably similar. The exchange of goods, knowledge, technologies, and ideas had a lasting impact on the civilizations along these routes, shaping their development in ways that continue to resonate in modern history.

Taklamakan near Yarkant. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

In this post, we therefore take a closer look at the historical development of the Silk Road and how it facilitated the exchange of key goods, ideas, and cultural practices across Asia, the Middle East, and Europe.

Historical development of the Silk Road

The origins of the Silk Road can be traced back to the early trade networks of Central Asia during the 2nd millennium BCE. However, the Silk Road as a coherent system of trade routes began to take shape during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), when Emperor Wu of Han initiated diplomatic missions to Central Asia under the leadership of Zhang Qian in 138 BCE. These missions aimed to secure alliances against the Xiongnu nomads and opened direct trade links between China and regions to the west.

The network of the ancient Silk Road and connected trade routes in the 1st century CE. Several key cities and regions played pivotal roles in the functioning of the Silk Road: Chang’an (modern Xi’an, China; the eastern terminus of the Silk Road and a major cultural and political center of ancient China, Dunhuang (China; a key oasis city where the northern and southern Silk Road routes diverged; it is famous for the Mogao Caves, which house a vast collection of Buddhist art and manuscripts), Samarkand and Bukhara (Central Asia; major trading hubs and cultural centers in the region of modern Uzbekistan), Merv (modern Turkmenistan; an important city in the Persian Empire and a key stop on the Silk Road), Palmyra (Syria; a vital trade city in the Roman Empire, connecting the Silk Road with Mediterranean markets), and Constantinople (the western terminus of the Silk Road, serving as a gateway to Europe). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Zhang Qian’s expeditions revealed the existence of thriving civilizations in Central Asia, Persia, and India, leading to the establishment of trade routes that became known as the Silk Road. The route derived its name from one of its most valuable commodities: Chinese silk, which was highly prized in the West. Over time, the Silk Road expanded into a complex network of overland and maritime routes, facilitating trade and cultural exchange across continents.

Chinese customs station on the Silk Road near Dunhuang. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

A Westerner on a camel, Northern Wei dynasty (386–534). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Maritime Silk Road: Austronesian proto-historic and historic maritime trade network in Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 1.0)

Relief panel of a Borobudur ship from the 8th century CE, they were depictions of large Javanese outrigger vessels. Shown with the characteristic tanja sail of Southeast Asian Austronesians. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.5)

Key goods exchanged on the Silk Road

While silk was the most famous product traded along the Silk Road, many other goods flowed through this ancient network, contributing to the prosperity and cultural enrichment of the regions involved.

Left: Yuan dynasty era celadon vase from Mogadishu, 13th - 14th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Indian art also found its way into Italy: In 1938 the Pompeii Lakshmi was found in the ruins of Pompeii. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

From China

China was the starting point of the Silk Road, and its goods were among the most coveted across the network. Silk, in particular, was a primary export and symbol of wealth and luxury in the West. Chinese porcelain, known as “china” in Europe, was prized for its fine craftsmanship and aesthetic appeal, becoming a significant trade commodity. The spread of paper-making technology from China revolutionized record-keeping and communication in the Islamic world and Europe, marking one of the most influential technological exchanges facilitated by the Silk Road. Another notable Chinese product, tea, though initially less prominent, later emerged as a vital export and became integral to cultural practices far beyond China.

From Central Asia and India

Central Asia and India also played crucial roles in Silk Road trade, offering products that met the diverse demands of traders and consumers along the route. Central Asian horses were highly valued by Chinese armies for their strength and stamina, significantly enhancing China’s military capabilities. From India, spices such as pepper and cinnamon were in high demand both in Eastern and Western markets, valued for their culinary and medicinal uses. Precious stones, including lapis lazuli and jade, added to the allure of trade, while textiles like wool, cotton, and intricately embroidered fabrics enriched the variety of goods exchanged.

From Persia and the Middle East

Persia and the Middle East contributed a wide array of luxury items and practical goods. Persian glassware, renowned for its clarity and artistry, found eager buyers across Asia and Europe. Carpets from Persia and Central Asia became iconic luxury items, symbolizing wealth and cultural refinement. Metals, including gold, silver, and bronze, were not only traded as raw materials but also as intricately crafted artifacts. Additionally, incense and perfumes, particularly frankincense and myrrh from Arabia, were in high demand for religious ceremonies and personal use, adding a sensory dimension to the cultural exchanges along the Silk Road.

From Europe and the Mediterranean

Europe and the Mediterranean regions, though situated at the western end of the Silk Road, contributed goods that appealed to Eastern markets. Wine from the Mediterranean was a popular luxury product in China and Central Asia. Olive oil, used for cooking, lighting, and religious rituals, was another important export. Roman and Byzantine metalwork, particularly weapons and armor, were sought after for their superior quality. Fine glassware and jewelry from these regions found markets in the East, completing the diverse array of goods exchanged along the Silk Road.

Marco Polo’s caravan on the Silk Road, 1380. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Exchange of ideas and cultural interaction

Beyond the exchange of goods, the Silk Road served as a conduit for the transmission of ideas, religions, and technologies, profoundly influencing the development of civilizations across Asia, the Middle East, and Europe.

Religions

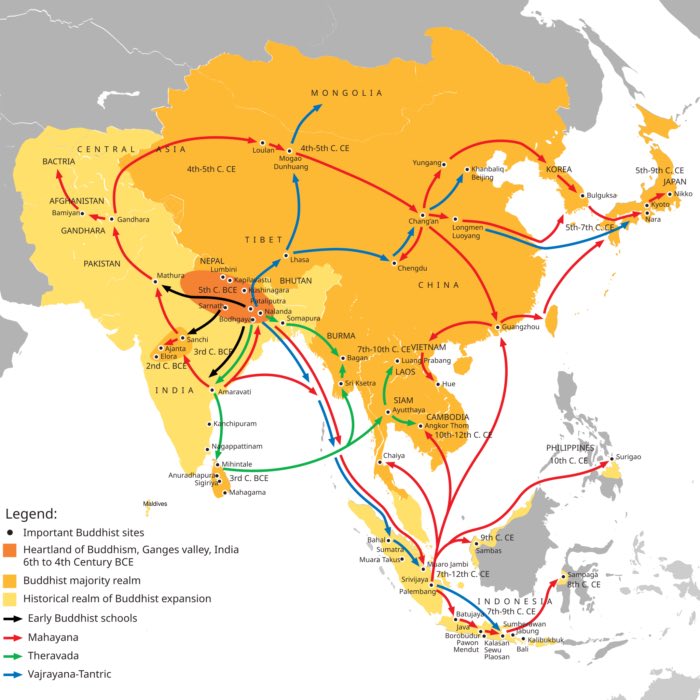

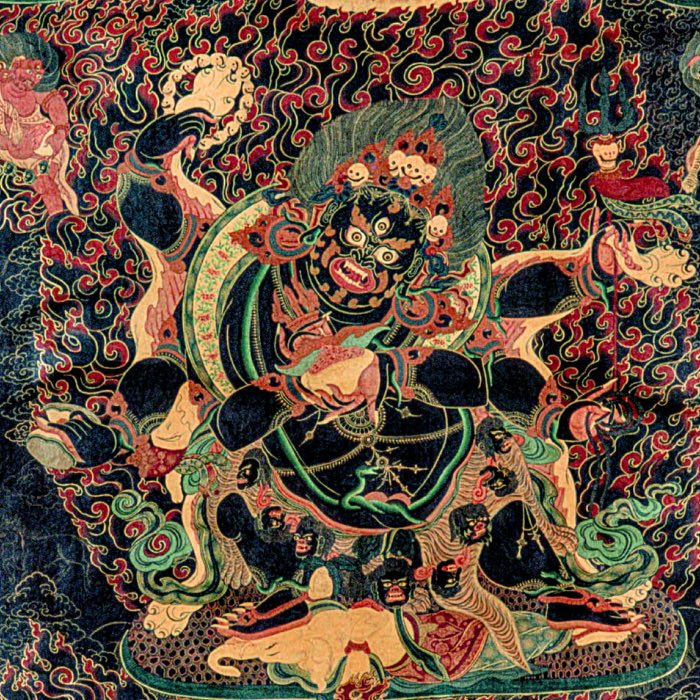

The Silk Road facilitated the spread of major world religions, fostering religious pluralism and cultural enrichment. Buddhism, originating in India, traveled along the trade routes to Central Asia, China, Korea, and Japan. Monasteries and stupas established along these routes provided rest stops for travelers and became centers of learning and devotion. Zoroastrianism, the ancient religion of Persia, spread eastward into Central Asia, influencing the religious practices of many nomadic tribes. Similarly, Manichaeism, a syncretic religion founded by the prophet Mani in Persia, reached China by the 7th century CE, adding to the religious diversity along the Silk Road.

The Silk Road transmission of Buddhism: Mahayana Buddhism first entered the Chinese Empire (Han dynasty) during the Kushan Era. The overland and maritime “Silk Roads” were interlinked and complementary, forming what scholars have called the “great circle of Buddhism”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Left: A West Asian and a Chinese monk, Thousand Buddha Caves of Bäzäklik, 9th century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0) – Right: Fragment of a wall painting depicting Buddha from a stupa in Miran along the Silk Road, 200–400 CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

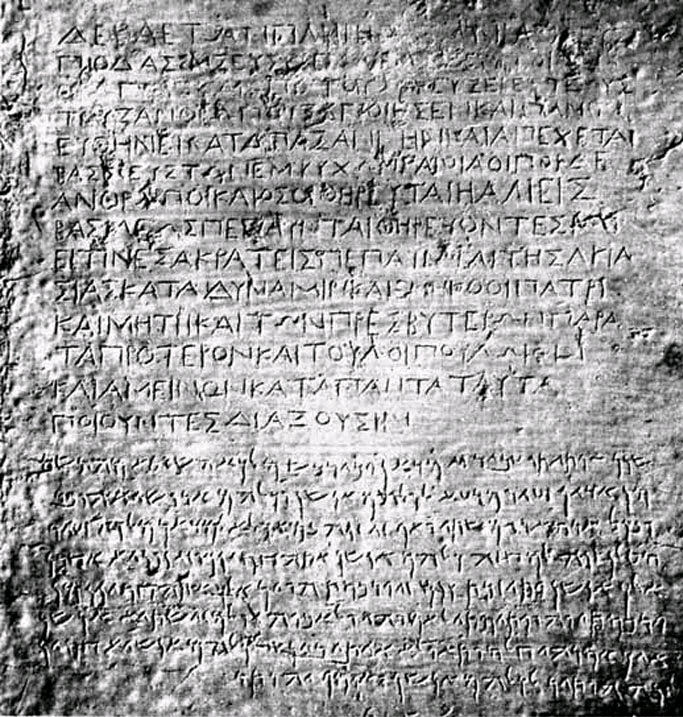

Left: Bilingual edict, Greek and Aramaic, by Indian Buddhist King Ashoka at Kandahar (Shar-i-kuna), 3rd century BCE. This edict advocates the adoption of “godliness” using the Greek term Eusebeia for Dharma. Preserved at Kabul Museum. Today disappeared. Two-dimensional inscription. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Statue depicting Buddha giving a sermon, from Sarnath, 3,000 km southwest of Urumqi, Xinjiang, 8th century CE. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

Islam spread rapidly along the Silk Road following the Islamic conquests of the 7th century CE, profoundly shaping the cultures of Central Asia, Persia, and parts of China. Meanwhile, Nestorian Christianity, a branch of Eastern Christianity, established communities in major cities along the trade routes, contributing to the rich tapestry of religious life on the Silk Road.

The Nestorian Stele, created in 781, describes the introduction of Nestorian Christianity to China. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Technologies

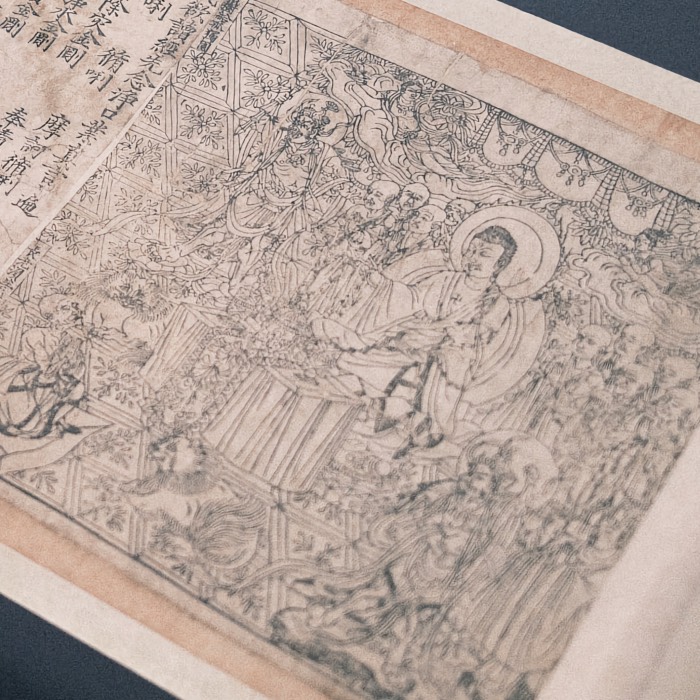

The exchange of technologies was another significant aspect of Silk Road interactions. Chinese innovations such as paper-making and printing spread westward, revolutionizing communication and record-keeping in the Islamic world and Europe. Gunpowder, initially invented in China, reached the Islamic world and eventually Europe, where it profoundly altered the nature of warfare.

Left: A qanat is a traditional form of fresh water extraction, usually in desert areas, to obtain drinking and industrial water from higher regions. It consists of a mother well, several vertical access shafts and the qanat channel. The qanat channel is a gravity-fed tunnel that runs at a slight gradient from the mother well via the access shafts to the qanat outlet. The qanat system was developed in Persia over 2,000 years ago and spread to other regions, including China and North Africa. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Channel of the qanats of Ghasabeh in Iran’s Razavi Khorasan Province. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Persian and Central Asian innovations in irrigation, such as the qanat system, influenced agricultural practices in China and beyond, enhancing food production and supporting growing populations. Medical knowledge, including herbal remedies and surgical techniques, was also exchanged, enriching the medical traditions of different civilizations.

Art and culture

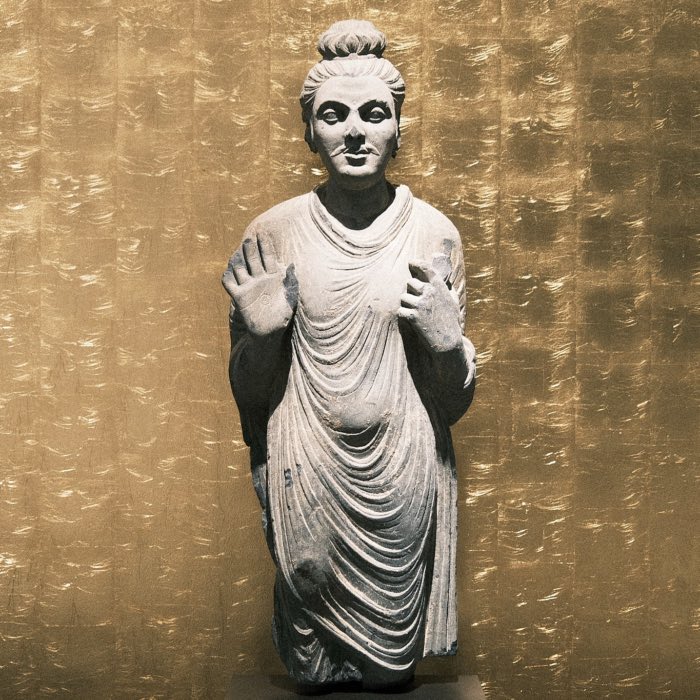

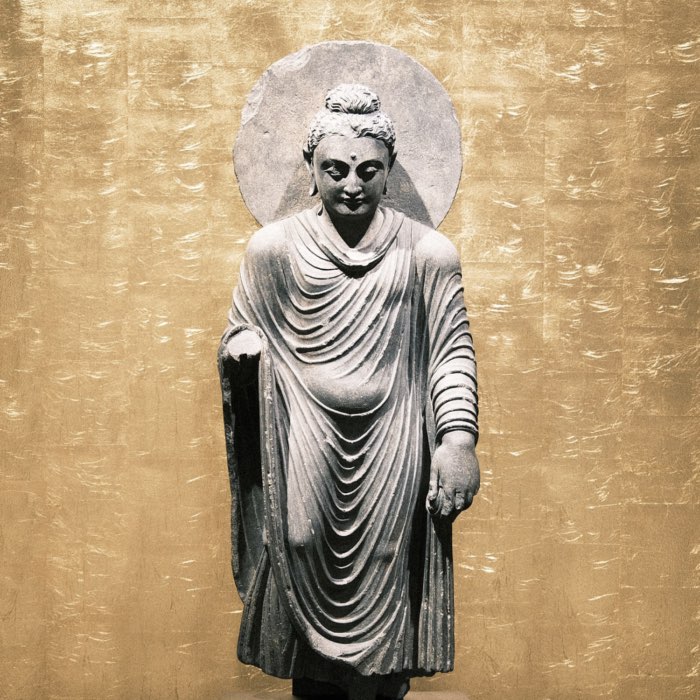

Artistic styles and cultural motifs were exchanged along the Silk Road, resulting in a fusion of artistic traditions. Greco-Buddhist art (see also this post), emerging from the interaction between Hellenistic art and Buddhist traditions in Gandhara (modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan), influenced Buddhist iconography in China and beyond. The introduction of new textiles and clothing styles transformed fashion trends across regions. Literary works, such as The Journey to the West in China, were inspired by the cultural interactions facilitated by the Silk Road, reflecting the deep impact of these exchanges on storytelling and cultural expression.

Iconographical evolution of the Wind God. Left: Greek wind god from Hadda, 2nd century CE. Middle: Wind god from Kizil, Tarim Basin, 7th century CE. Right: Japanese wind god Fujin, 17th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Decline of the Silk Road

The decline of the Silk Road began in the late medieval period due to a combination of political, economic, and environmental factors. One of the primary causes was the fall of empires that had previously maintained and secured the trade routes. The Mongol Empire, which had provided a relatively stable and safe environment for merchants during its height in the 13th and early 14th centuries, began to fragment in the mid-14th century. As political instability increased, so did the risks associated with long-distance overland trade. Without the centralized control that had once ensured safety, merchants faced greater threats from banditry, regional conflicts, and deteriorating infrastructure, leading to a significant decline in trade activity.

Simultaneously, the rise of maritime trade provided an alternative, more efficient means of transporting goods. The Age of Exploration, spearheaded by European powers such as Portugal and Spain, opened up sea routes to Asia. The discovery of a direct sea route to India by Vasco da Gama in 1498 drastically reduced the reliance on the overland Silk Road. Maritime trade offered several advantages: ships could carry larger quantities of goods, the routes were faster, and the risks of piracy, while still present, were often less severe than the dangers of traversing vast deserts and mountainous terrain. The burgeoning spice trade, in particular, shifted to the sea, drawing economic activity away from the Silk Road.

Another significant factor was the spread of plagues and diseases, most notably the Black Death, which devastated populations along the Silk Road in the 14th century. The pandemic, which originated in Central Asia, spread to Europe via the Silk Road and maritime routes, killing an estimated 25 to 30 million people in Europe alone. This catastrophic loss of life disrupted societies, economies, and trade networks, further diminishing the flow of commerce along the overland routes.

The plague in Phrygia, copperplate engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi, 1515/1516. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

By the 16th century, the combination of political fragmentation, the rise of maritime trade, and the lingering effects of repeated outbreaks of disease had rendered the Silk Road largely obsolete. Although certain segments of the route continued to function as regional trade networks, the grand overland system that had once connected distant civilizations had effectively fallen into disuse. Nevertheless, the legacy of the Silk Road endured, leaving a lasting imprint on the cultures, economies, and histories of the regions it once linked.

Conclusion

The Silk Road was far more than a network of trade routes; it was a bridge that connected diverse civilizations, fostering economic prosperity, cultural exchange, and intellectual advancement across continents. It not only facilitated the trade of valuable goods such as silk, spices, and precious metals but also enabled the transmission of ideas, religious beliefs, and technologies that profoundly shaped the course of human history. The spread of Buddhism, the exchange of medical knowledge, and the dissemination of innovations like paper-making and gunpowder were all byproducts of this ancient global interaction.

By linking East and West, the Silk Road laid the groundwork for early globalization, creating pathways for mutual influence and cultural enrichment. Even as overland trade declined with the rise of maritime routes, the legacy of the Silk Road endures in the historical relationships it fostered and the lasting impact it had on the civilizations it touched.

Today, efforts like China’s Belt and Road Initiative seek to revive the spirit of the Silk Road by promoting trade, cultural dialogue, and cooperation across regions, drawing inspiration from this ancient conduit of exchange. The history of the Silk Road offers timeless lessons on the power of connectivity, mutual respect, and the benefits of intercultural dialogue.

The ruins of a Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) Chinese watchtower made of rammed earth at Dunhuang, Gansu province, China. Located along what was the old line of rammed-earth fortifications that once stretched from the Hexi Corridor (in Gansu) to the Tarim Basin (in present day Xinjiang). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 2.0)

References

- Hansen, Valerie, The Silk Road: A new history with documents, 2016, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0190208929

- Whitfield, Susan, Life along the Silk Road, 2015, University of California Press, ISBN: 978-0520280595

- Liu, Xinru, The Silk Road in world history, 2010, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195338102

- Richard Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of Globalization, 2010, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN: 9780230621251

- Lewis R. Lancaster, The Buddhist Maritime Silk Road, 2022, Fo Guang Shan Institute of Humanistic Buddhism, ISBN: 9789574576326

- Marsha Smith Weidner, Cultural intersections in later Chinese Buddhism, 2001, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 9780824823085

- Christopher I. Beckwith, Empires Of The Silk Road - A History Of Central Eurasia From The Bronze Age To The Present, 2009, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 9780691135892

comments