The Second Urbanization in ancient India

The Second Urbanization refers to a pivotal historical period in the Indian subcontinent, roughly dated between 600 and 300 BCE, when urban life re-emerged on a significant scale after a long phase of predominantly rural and pastoral societies following the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization. This era saw the rise of new cities, trade networks, social structures, and intellectual currents, laying the groundwork for transformative religious and philosophical developments — including early Buddhism and Jainism.

Relief showing Bimbisara with his royal cortege issuing from the city of Rajagriha to visit the Buddha, Sanchi, East Face, South Pillar, East Gateway. Depicted sceneries like these illustrate the urban life of the time during the Second Urbanization. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Historical Context

The first urban civilization of the Indian subcontinent — the Indus Valley Civilization — flourished from around 2600 to 1900 BCE and was centered on highly planned cities like Harappa and Mohenjo-daro. These cities featured complex drainage systems, standardized weights and measures, large-scale storage facilities, and long-distance trade with Mesopotamia. After the decline of this civilization, likely due to environmental and economic shifts, the subcontinent entered a long phase without major urban centers.

During this interim period (roughly 1900–600 BCE), life became increasingly decentralized. The population relied on agriculture and lived in rural villages, with local tribal and clan-based societies. Vedic culture emerged during this phase, largely due to the eastward migration of Indo-Aryan-speaking pastoral groups and their interaction with local agrarian communities. As these groups settled into the fertile northern plains, they preserved and transmitted their cultural identity through oral traditions such as the Rigveda. Their worldview emphasized sacrificial rituals, hymns to natural forces, and a social structure centered on cattle wealth, kinship, and mobile pastoralism, rather than urban infrastructure or centralized political authority. Political units were small and often kin-based, and social organization was fluid compared to later caste structures.

The Second Urbanization, beginning around 600 BCE, marked a dramatic shift. Urban centers reappeared, particularly in the Gangetic plains, driven by new iron technology, expanded agriculture, increasing trade, and the formation of more centralized political states. This period saw not just the physical growth of cities but a transformation in how societies were organized and how people thought about power, social mobility, and spiritual practice.

Key factors contributing to this urban revival included:

- The widespread use of iron tools and ploughs, which allowed for more intensive agriculture, food surplus, and population growth, creating the material conditions for urban settlements.

- The growth of trade and craft specialization, which encouraged the rise of market towns and guild-based economies.

- The development of stable political entities, such as the Mahājanapadas (great states), which provided security, taxation systems, and infrastructure conducive to urban development.

The Mahājanapadas

Sixteen major states, known as Mahājanapadas, emerged during this period as political formations of unprecedented scale and complexity in the post-Vedic world. Some, like Magadha and Kosala, developed into powerful monarchies with standing armies, bureaucracies, and expanding urban capitals. Others, such as the Śākyas and Licchavis, functioned as oligarchic republics (gaṇa-saṅghas), where governance was carried out by assemblies of elders or clan representatives.

The Mahājanapadas were sixteen major polities concentrated in the Indo-Gangetic Plain. Their rise marked a transformative phase in the political and cultural history of ancient India, fostering trade, urban growth, and philosophical exchange. Cities like Pāṭaliputra (modern Patna) in Magadha flourished as centers of commerce and statecraft. Within the territory of Kosala lay the Śākya clan — a republican gaṇa-saṅgha based in the Himalayan foothills near present-day Nepal. Siddhartha Gautama, later known as the Buddha, was born into this oligarchic polity. Though the Śākyas maintained internal autonomy through their own assembly, they were politically subordinate to the Kosalan monarchy — a layered relationship that reflects the complex power structures of the Mahājanapada period. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

These emerging states played a foundational role in supporting the rise of cities by organizing infrastructure, enforcing legal systems, managing taxation, and securing trade routes. Their political stability allowed surplus resources to be directed toward urban construction, public works, and market regulation. Administrative centers became hubs of power and commerce, often attracting monks, philosophers, artisans, and merchants alike. In this way, the Mahājanapadas were both agents and beneficiaries of the Second Urbanization, facilitating a new socio-political landscape shaped by urban life and statecraft.

Urbanization and economy

Cities such as Rājagaha, Vesālī, Sāvatthī, and later Pāṭaliputra became focal points of both political authority and commercial dynamism. Their emergence marked a significant shift from rural self-sufficiency to interconnected, urban economies. The expansion of agriculture enabled surplus production, which in turn fueled the rise of marketplaces and long-distance trade routes — by land and river.

Coinage began to appear as a standardized medium of exchange, facilitating more complex economic transactions across regions. Standardized weights and measures further enhanced commercial trust and consistency. These developments supported the growth of urban professions: from metalworkers and weavers to scribes, architects, and caravan leaders.

Artisan guilds (śreṇīs) organized production, protected trade secrets, and negotiated collectively with urban authorities. Meanwhile, a new class of urban elites — wealthy merchants and landowners — began to exert social and political influence, often becoming patrons of temples, schools, and ascetic communities. This growing urban economy did not just alter patterns of wealth, but reshaped the very structure of society, creating new opportunities for mobility, specialization, and interaction across social boundaries.

Social change

The rise of cities during the Second Urbanization significantly disrupted established social hierarchies and challenged the rigidity of the developing caste system (varna-jāti). While Brahminical ideology was increasingly formalizing inherited status and occupational roles, urban environments introduced alternative social dynamics. Cities brought together individuals from diverse regions and backgrounds — traders, artisans, laborers, teachers, ascetics, and thinkers — who interacted in marketplaces, guilds, forums, and monasteries.

Urban life enabled professions to flourish outside the control of ritual or lineage. A potter, merchant, or physician could gain status through skill and reputation, not merely by birth. Philosophical discussions and public debates invited participation from various strata of society, including those excluded from Vedic rituals. Women, too, though still constrained by patriarchy, found greater space in certain urban professions and religious circles.

In this environment, personal merit and adaptability began to rival hereditary privilege. The city thus became not only a center of trade and administration, but also a crucible for new identities, values, and social aspirations.

Intellectual and religious developments

The Second Urbanization created the social and intellectual conditions for the emergence of radical new religious and philosophical traditions. The Vedic tradition, which had long centered around hereditary ritual authority, sacrifice, and social hierarchy, began to face sharp criticism from a growing counterculture of wandering ascetics and independent thinkers known collectively as śramaṇas.

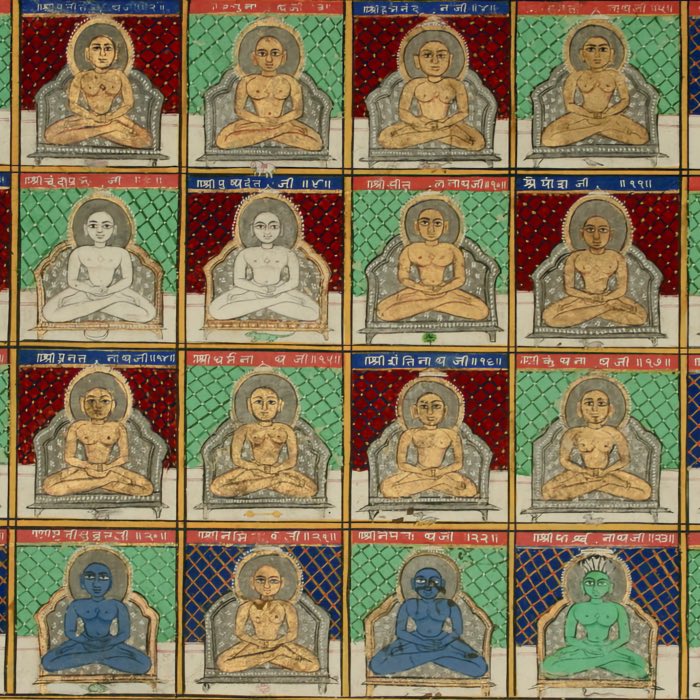

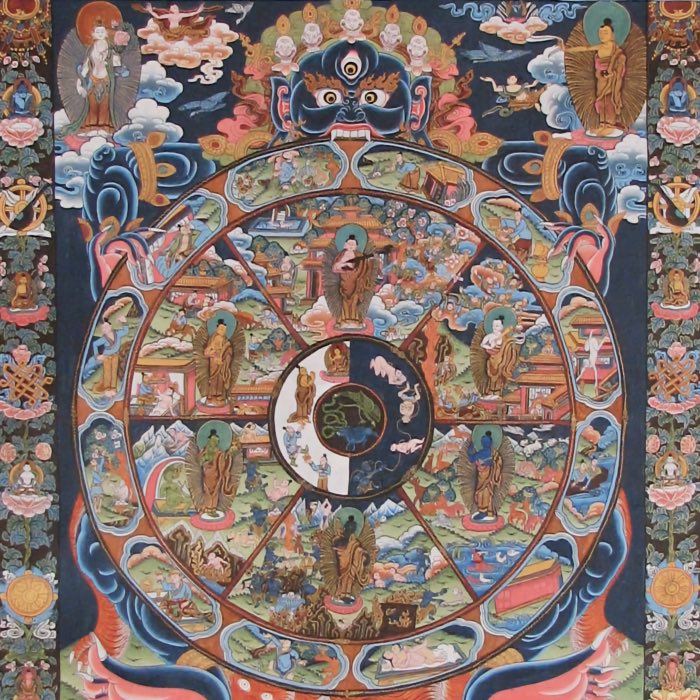

These figures did not merely reject the authority of the Brahmins — they questioned the very foundations of Vedic cosmology, karma theory, and social stratification. In place of ritual and sacrifice, they emphasized personal insight, ethical behavior, meditative discipline, and renunciation as the path to liberation. Among these movements, Jainism emphasized strict non-violence and ascetic purification, while the Ājīvikas promoted a deterministic cosmology governed by fate. The teachings of Siddhartha Gautama (the historical Buddha) developed a distinctive path focused on dependent origination, suffering, and the cessation of craving.

The increasingly pluralistic urban environment was essential to the growth of these movements. Cities offered the density, diversity, and discursive openness needed for these ideas to circulate, be refined, and gain followers. Public debate, royal patronage, and lay support helped institutionalize what were initially marginal or oppositional voices. In many ways, the śramaṇa movements were not just religious alternatives — they were direct responses to the spiritual crisis and social transformations brought about by urbanization itself.

Global parallels and contemporaneous developments

To fully grasp the importance of the Second Urbanization in India, it is instructive to compare it with developments occurring in other regions of the world around the same time. Between roughly 600 and 300 BCE, many ancient civilizations were undergoing transformative shifts in political organization, urban development, and philosophical or religious thought — an epoch that some scholars refer to as the “Axial Age”.

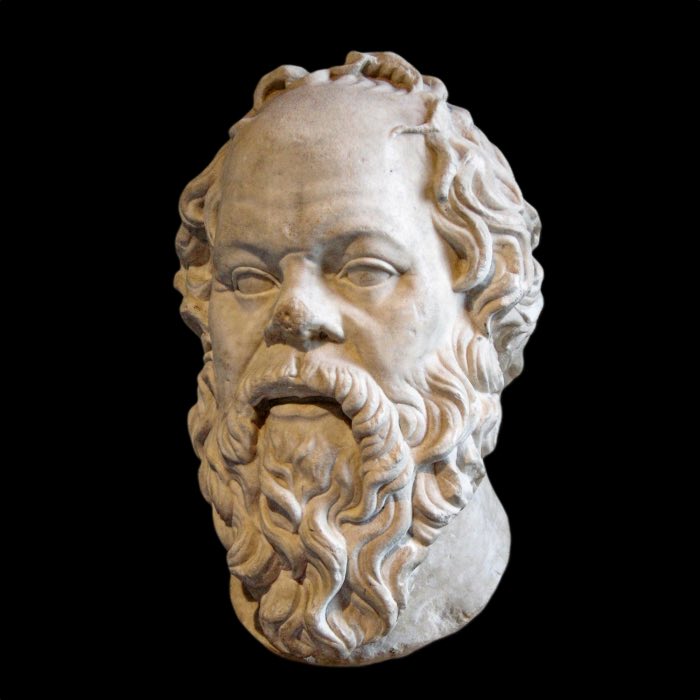

In the Mediterranean world, Greek city-states (poleis) were flourishing, engaging in experiments with democracy (e.g., in Athens), expanding philosophical thought through figures like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, and developing institutional frameworks of civic governance. Meanwhile, in Persia, the Achaemenid Empire established one of the most sophisticated bureaucratic and infrastructural systems of the ancient world.

In China, the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (especially during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods) saw the rise of major philosophical schools such as Confucianism, Daoism, Legalism, and Mohism. These emerged in response to political fragmentation and social instability, much like the śramaṇa movements in India.

In Mesopotamia, though its earlier empires had waned, the Neo-Babylonian and Persian periods maintained urban continuity and preserved scholarly traditions in astronomy, law, and literature. Egypt, too, under late dynastic rule and later Persian influence, continued as an important religious and political center.

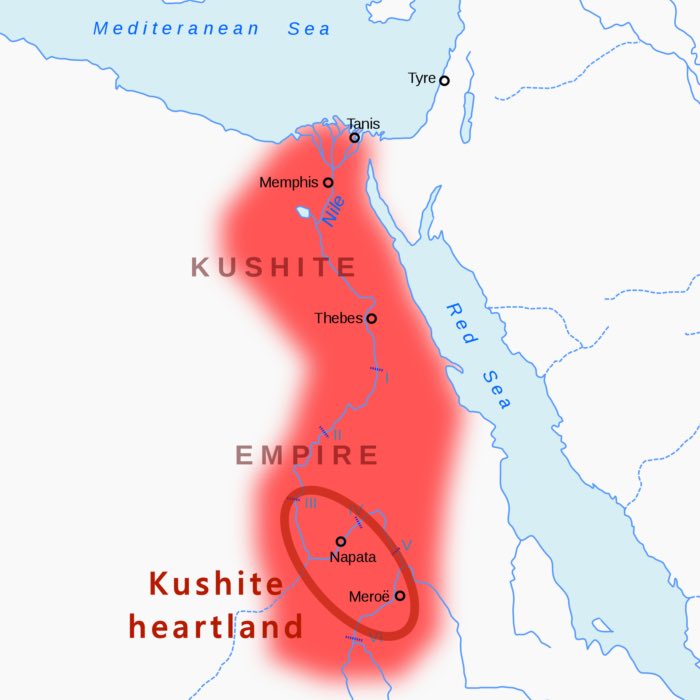

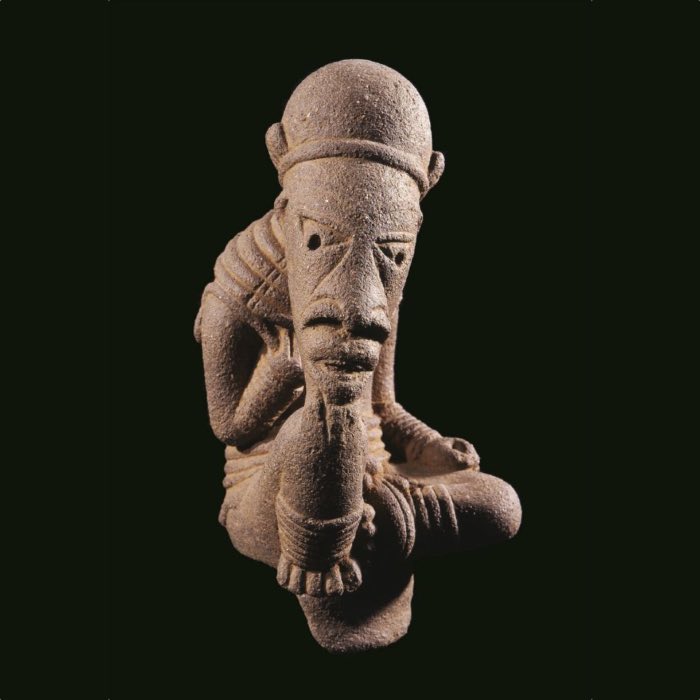

On the African continent, the Kingdom of Kush (in present-day Sudan) maintained urban centers and a complex state apparatus with its own script and temple architecture. Across the Sahel and West Africa, proto-urban settlements such as those in the Nok culture began to form, though large-scale urbanization would emerge later.

In the Americas, major urban civilizations were not yet fully developed in this timeframe. However, cultures like the Olmec in Mesoamerica and the Chavín in the Andes laid the cultural and religious foundations for later complex societies such as the Maya and the Inca.

These cross-regional parallels suggest that the Second Urbanization in India was part of a broader global pattern of transformation. Across continents, societies were consolidating political power, establishing cities, and giving rise to new religious and philosophical systems that would shape human thought for millennia.

Later developments and historical trajectory

The momentum of the Second Urbanization did not fade quickly. Instead, it laid the institutional and cultural groundwork for the rise of large imperial formations in India, most notably the Maurya Empire (c. 321–185 BCE). Under Chandragupta Maurya and especially Emperor Aśoka, urbanization continued to expand, administrative structures became more centralized, and Buddhism began to spread far beyond its original heartland through royal patronage and missionary efforts.

Urban centers such as Pāṭaliputra evolved into major imperial capitals, with sophisticated infrastructure and cosmopolitan populations. The political unification achieved by the Mauryas reinforced the urban networks and trade routes established during the earlier period. Although some regional powers experienced temporary fragmentation after the Mauryan collapse, the broader trajectory of urban and intellectual life endured, especially in the eastern and southern parts of the subcontinent.

Later periods — such as the Gupta Empire (c. 320–550 CE) — would see further cultural flourishing, sometimes called a “classical age”, in literature, art, and science. By then, the idea of the city as a center of power, commerce, and learning was deeply entrenched. The Second Urbanization, therefore, was not a short-lived renaissance but the foundation of a long-term transformation.

Conclusion

The Second Urbanization represents a watershed moment in South Asian history, marking a transition from tribal, pastoral, and rural life to complex urban societies characterized by economic specialization, political centralization, and vibrant intellectual pluralism. Between 600 and 300 BCE, the Gangetic plains became a crucible for state formation, economic exchange, and spiritual reinvention.

This transformation was supported by advancements in iron technology, agricultural intensification, and the rise of the Mahājanapadas, which provided the institutional backbone for urban life. Cities emerged not merely as sites of trade and governance, but as arenas where new ideas, social norms, and alternative models of human flourishing could take root. The urban setting enabled a loosening of inherited identities, opening space for merit-based status and heterodox voices.

The emergence of the śramaṇa movements — including Jainism, Ājīvika, and early Buddhism — must be seen in this broader context. They were not outliers but expressions of a deeper cultural and spiritual ferment triggered by the changing material and social environment. The Second Urbanization gave rise to the conditions in which people could question ritual orthodoxy, imagine ethical self-cultivation, and explore universal questions of suffering, impermanence, and liberation.

In comparative perspective, the Indian Second Urbanization stands alongside other transformative epochs in world history. It was contemporaneous with the rise of philosophical schools in Zhou Dynasty China, the political and intellectual ferment of Classical Greece, the imperial synthesis of Achaemenid Persia, and the formative cultural developments in Mesoamerica and the Andes. Each of these regions witnessed parallel shifts — toward urbanization, ethical reflection, and institutional innovation — even if shaped by distinct local trajectories.

The significance of the Second Urbanization lies in its generative power. It set in motion civilizational patterns that would shape South Asia for centuries, from its religious institutions and textual traditions to its political configurations and social critiques. It was not merely a return to the city, but a rebirth of civilization itself.

References

- Upinder Singh, A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India, 2009, Pearson Education, ISBN: 978-8131716779

- Romila Thapar, Early India: From the Origins to CE 1300, 2003, Penguin, ISBN: 978-0143029892

- A.L. Basham, The Wonder That Was India, 1985, Sidgwick & Jackson, ISBN: 978-0283992575

- John Keay, India: A History, 2022, William Collins, ISBN: 978-0007307753

- Gregory Possehl, The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective, 2010, Altamira, ISBN: 978-8178292915

- R.S. Sharma, India’s Ancient Past, 2011, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195687859

- D.N. Jha, Ancient India in Historical Outline, 2006, Manohar Publishers, ISBN: 978-8173042164

- Burton Stein, A History of India, 2010, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 978-1405195096

- S.R. Rao, Lothal and the Indus Civilization, 1974, Asia Publishing House, ISBN: 978-0210222782

- Michel Danino, The Lost River: On the Trail of the Sarasvati, 2010, Penguin Books, ISBN: 978-0143068648

- McIntosh, Jane, The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives, 2008, ISBN: 978-1-57607-907

- Bryant, E. F.,The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate, 2004, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0195169478

- Flood, G., An Introduction to Hinduism, 1996, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521438780

- Boyce, M., Zoroastrians: their religious beliefs and practices, 1979, Routledge, ISBN: 978-0415239035

- Parpola, A., The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization, 2015, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 978-0190226923

- Wikipedia article on the History of Indiaꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Indus Valley Civilizationꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Indo-Mesopotamia relationsꜛ

- [Wikipedia article on the Religion of the Indus Valley Civilisation](Indo-Mesopotamia relationsꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Vedic periodꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Maurya Empireꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Gupta Empireꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Mahajanapadasꜛ

comments