Sāṃkhya: The dualistic philosophy of Indian metaphysics

Sāṃkhya, one of the oldest and most influential schools of Indian philosophy, is a dualistic system that seeks to explain the nature of reality and the means to attain liberation (mokṣa). It is considered one of the six orthodox (āstika) schools because it accepts the authority of the Vedas, but its teachings are largely independent of Vedic ritualism and theology. Sāṃkhya’s metaphysical framework, centered on the distinction between puruṣa (consciousness) and prakṛti (matter), has significantly influenced other Indian philosophies, including Yoga and early Buddhism.

Sāṃkhya, interpreted by DALL•E, “symbolizing the dualism of Purusha (consciousness) and Prakriti (matter) using continuous flowing lines in a balanced and abstract style”.

Origins and historical development

The origins of Sāṃkhya can be traced back to the Upanishads, particularly the Kaṭha Upanishad and Śvetāśvatara Upanishad, which contain dualistic themes and discussions on self-realization. However, Sāṃkhya developed into a systematic school with its own metaphysical doctrines around the 4th–3rd century BCE. The earliest extant text of Sāṃkhya is the Sāṃkhya Kārikā by Īśvarakṛṣṇa (circa 4th century CE), which codifies its key principles.

Though Sāṃkhya originally existed as an independent school, its practical teachings were closely associated with the Yoga school, particularly as outlined in Patañjali’s Yoga Sutras. Together, Sāṃkhya and Yoga offer a theoretical and practical approach to attaining liberation.

Key philosophical concepts

Sāṃkhya presents a dualistic cosmology, positing two fundamental and irreducible principles: puruṣa and prakṛti. Liberation involves understanding the distinction between these two principles and disentangling the self from the material world.

Puruṣa (pure consciousness)

Puruṣa is the eternal, conscious principle in Sāṃkhya. It is pure, unchanging, and passive, serving as the witness to all phenomena. Unlike the concept of ātman) in Vedanta, which is often equated with brahman, puruṣa in Sāṃkhya is plural—there are infinite puruṣas, each representing an individual self.

Key characteristics of puruṣa include:

- It is consciousness itself, devoid of any physical or mental qualities.

- It does not act but merely observes the activities of prakṛti.

- Liberation is achieved when puruṣa realizes its distinctness from prakṛti.

Prakṛti (matter or nature)

Prakṛti is the primal, unconscious substance from which the material world evolves. It is dynamic, composed of three guṇas (qualities), and responsible for all activity and change in the universe. Unlike puruṣa, which is passive and unchanging, prakṛti is active and constantly in flux.

The three guṇas of prakṛti are:

- Sattva: The quality of balance, purity, and knowledge.

- Rajas: The quality of activity, energy, and passion.

- Tamas: The quality of inertia, darkness, and ignorance.

These guṇas are present in all material entities in varying proportions and account for the diversity of forms and experiences in the world.

Evolution of the universe

According to Sāṃkhya, the universe evolves when prakṛti, under the influence of puruṣa, undergoes a process of transformation. This process begins with the disturbance of the equilibrium of the guṇas, leading to the manifestation of various elements and faculties. The sequence of evolution includes:

- Mahad (intellect or cosmic intelligence): The first product of prakṛti, responsible for discernment.

- Ahaṅkāra (ego): The principle of individuation, which gives rise to a sense of “I” and “mine.”

- Manas (mind): The faculty of thought and perception.

- Indriyas (sense and action organs): The five sensory organs (ears, skin, eyes, tongue, and nose) and five organs of action (speech, hands, feet, excretion, and reproduction).

- Tanmātras (subtle elements): The five subtle elements—sound, touch, form, taste, and smell.

- Mahābhūtas (gross elements): The five gross elements—ether, air, fire, water, and earth.

This cosmology describes the world as a complex interaction of material principles, which evolve without any need for a creator deity.

Bondage and liberation

In Sāṃkhya, bondage occurs when puruṣa falsely identifies with prakṛti and becomes entangled in the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsāra). This identification arises from ignorance (avidyā) of the true nature of puruṣa. The goal of life is to attain liberation (kaivalya), which involves the following:

- Discrimination (viveka): Realizing the distinction between puruṣa and prakṛti through knowledge.

- Detachment (vairāgya): Letting go of attachment to material pleasures and desires.

- Freedom from karma: Since actions belong to prakṛti, the self becomes free from karma when it ceases to identify with the body and mind.

Liberation in Sāṃkhya is characterized by complete separation of puruṣa from prakṛti, resulting in eternal peace and self-awareness.

Sāṃkhya’s influence on Indian philosophy

Sāṃkhya’s dualistic framework and cosmological doctrines have had a significant impact on other Indian philosophical systems:

- Yoga: Patañjali’s Yoga Sutras adopt Sāṃkhya’s metaphysical framework almost entirely but emphasize the practical aspects of meditation and self-discipline as the means to liberation.

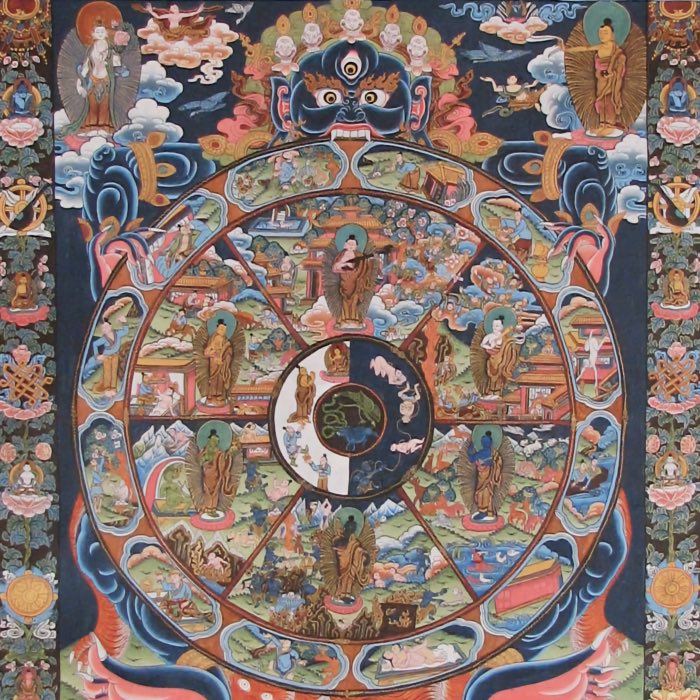

- Buddhism: Early Buddhist thought shares similarities with Sāṃkhya, particularly in its rejection of a creator god and its emphasis on understanding the nature of reality to overcome suffering.

- Vedanta: While Vedanta ultimately rejects Sāṃkhya’s dualism in favor of monism, it engages deeply with Sāṃkhya’s analysis of the self and the material world.

Criticisms of Sāṃkhya

Sāṃkhya has been criticized by other philosophical schools, particularly Vedanta, for its dualistic ontology. Critics argue that positing two eternal principles — puruṣa and prakṛti — leads to metaphysical problems, such as explaining how unconscious matter (prakṛti) can act without the will of puruṣa.

Moreover, the idea of multiple puruṣas is seen as problematic by non-dualistic schools, which assert that the self is singular and universal.

Conclusion

Sāṃkhya represents a unique and influential school of Indian philosophy, offering a comprehensive framework for understanding the nature of reality and the means to attain liberation. Its dualistic distinction between puruṣa and prakṛti, emphasis on self-knowledge, and rigorous cosmological analysis have shaped the development of Indian thought for centuries. The historical impact of Sāṃkhya on other philosophical traditions underscores its relevance and significance in the intellectual history of India.

References and further reading

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Indian philosophy, vol. 1, 2018, FB&C LTD, ISBN: 978-0331594577

- M. Hiriyanna, Essentials of Indian philosophy, 1995, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120813045

- Larson, Classical Sāṃkhya: An interpretation of its history and meaning, 2001, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120805033

- Chandradhar Sharma, A critical survey of Indian philosophy, 2000, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN: 978-8120803657

- R. Puligandla, Fundamentals of Indian philosophy, 1997, D.K. Printworld, ISBN: 978-8124600863

comments